Practically-A-Book Review: Rootclaim $100,000 Lab Leak Debate

I. Saar’s COV-2

Saar Wilf is an ex-Israeli entrepreneur. Since 2016, he’s been developing a new form of reasoning, meant to transcend normal human bias.

His method - called Rootclaim - uses Bayesian reasoning, a branch of math that explains the right way to weigh evidence. This isn’t exactly new. Everyone supports Bayesian reasoning. The statisticians support it, I support it, Nate Silver wrote a whole book supporting it.

But the joke goes that you do Bayesian reasoning by doing normal reasoning while muttering “Bayes, Bayes, Bayes” under your breath. Nobody - not the statisticians, not Nate Silver, certainly not me - tries to do full Bayesian reasoning on fuzzy real-world problems. They’d be too hard to model. You’d make some philosophical mistake converting the situation into numbers, then end up much worse off than if you’d tried normal human intuition.

Rootclaim spent years working on this problem, until he was satisfied his method could avoid these kinds of pitfalls. Then they started posting analyses of different open problems to their site, rootclaim.com. Here are three:

For example, does Putin have cancer? We start with the prior for Russian men ages 60-69 having cancer (14.32%, according to health data). We adjust for Putin’s healthy lifestyle (-30% cancer risk) and lack of family history (-5%). Putin hasn’t vanished from the world stage for long periods of time, which seems about 4x more likely to be true if he didn’t have cancer than if he did. About half of cancer patients lose their hair, and Putin hasn’t, so we’ll divide by two. On the other hand, Putin’s face has gotten more swollen recently, which happens about six times more often to cancer patients than to others, so we’ll multiply by six. And so on and so forth, until we end up with the final calculation: 86% chance Putin doesn’t have cancer, too bad.

This is an unusual way to do things, but Saar claimed some early victories. For example, in a celebrity Israeli murder case, Saar used Rootclaim to determine that the main suspect was likely innocent, and a local mental patient had committed the crime; later, new DNA evidence seemed to back him up.

One other important fact about Saar: he is very rich. In 2008, he sold his fraud detection startup to PayPal for $169 million. Since then he’s founded more companies, made more good investments, and won hundreds of thousands of dollars in professional poker.

So, in the grand tradition of very rich people who think they have invented new forms of reasoning everywhere, Saar issued a monetary challenge. If you disagree with any of his Rootclaim analyses - you think Putin does have cancer, or whatever - he and the Rootclaim team will bet you $100,000 that they’re right. If the answer will come out eventually (eg wait to see when Putin dies), you can wait and see. Otherwise, he’ll accept all comers in video debates in front of a mutually-agreeable panel of judges.

Since then, Saar and his $100,000 offer have been a fixture of Internet debates everywhere. When I argued that Vitamin D didn’t help fight COVID (Saar thinks it does), people urged me to bet against Saar, and we had a good discussion before finally failing to agree on terms. When anti-vaccine multimillionaire Steve Kirsch made a similar offer, Saar took him up on it, although they’ve been bogged down in judge selection for the past year.

Rootclaim also found in favor of the lab leak hypothesis of COVID. When Saar talked about this on an old ACX comment thread, fellow commenter tgof137 (Peter Miller) agreed to take him up on his $100K bet.

At the time, I had no idea who Peter was. I kind of still don’t. He’s not Internet famous. He describes himself as a “physics student, programmer, and mountaineer” who “obsessively researches random topics”. After a family member got into lab leak a few years ago, he started investigating. Although he started somewhere between neutral and positive towards the hypothesis, he ended up “90%+” convinced it was false. He also ended up annoyed: contrarian bloggers were raking in Substack cash by promoting lab leak, but there seemed to be no incentive to defend zoonosis.

Unlike Saar, Peter was not especially rich. $100K represented a big fraction of his net worth. But (he wrote me an email):

It was a moderately large financial risk for me … I [expected] a smart and unbiased person would vote for zoonosis with, say, 80% odds after seeing all the evidence. If both judges voting for lab origin is uncorrelated, that’s 20% squared, and it was pretty low odds of a catastrophic financial risk for me.

I wasn’t highly worried about losing the debate because I was wrong about the science. I put in enough effort to know I’m probably correct there. My biggest fear was that I’d choke at the debate for some reason, that I’d be too anxious and particularly that I’d be unable to sleep the night beforehand. I have zero prior debate experience to rely upon.

If this seems like a weirdly blase attitude towards risk, Peter told blogger Philipp Markolin that he “is a mountain climber where sometimes there is a 5% chance to die, and the stakes are just not that high for a debate.”

Unlike the eternally bogged-down Saar-Kirsch debate, here things moved quickly. The two contestants put out a call for judges on the ACX subreddit, and agreed on:

-

Will van Treuren, a pharmaceutical entrepreneur with a PhD from Stanford and a background in bacteriology and immunology.

-

Eric Stansifer, an applied mathematician with a PhD from MIT and experience in mathematical virology.

…both of whom received $5,000 as payment for their ~1001 hours of work, paid by the two contestants along with their $100,000 table stakes2.

The format would be three sessions, each consisting of hour-and-a-half arguments by both sides, then three hours for the debaters to answer questions from the judges and each other.

II. The Debate

Below, I’ve included the videos from each session, plus my (long) summary if you prefer text. In the second session (on viral genetics) biotech entrepreneur and lab leak expert Yuri Deigin stood in for Saar; Peter continued to represent himself.

Session 1: Epidemiology

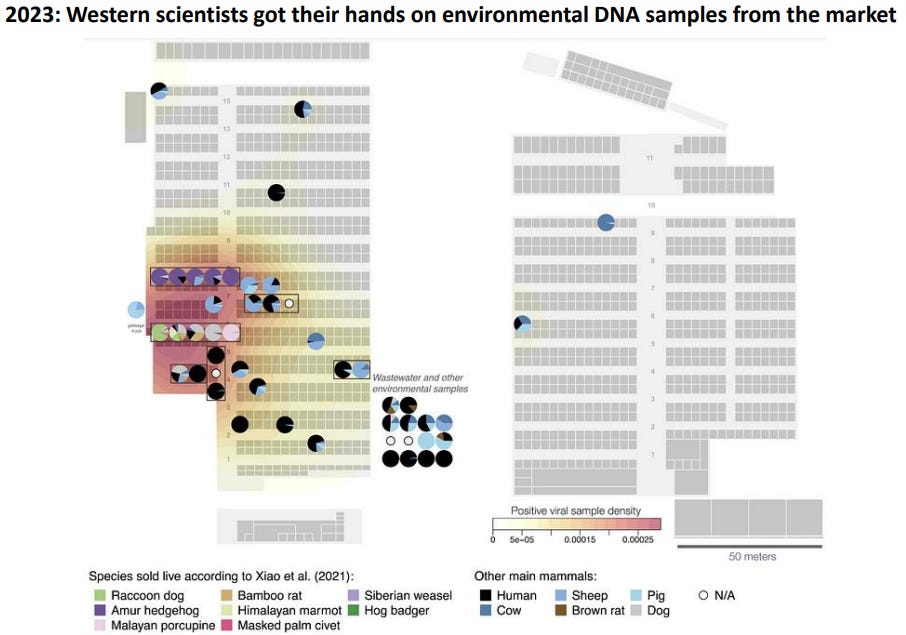

Peter: The first officially confirmed COVID case was a vendor at the Wuhan wet market. So were the next four, and half of the next 40. A heat map of early cases is obviously centered on the wet market, not on the lab. The wet market and the lab are about 6 miles away as the crow flies, or a 15 mile / half hour drive.

Location of COVID cases in December 2020. Source: NYT, slightly edited.

Location of COVID cases in December 2020. Source: NYT, slightly edited.

A map of cases at the wet market itself shows a clear pattern in favor of the very southwest corner:

The southwest corner is where most of the wildlife was being sold. Rumor said that included a stall with raccoon-dogs, an animal which is generally teeming with weird coronaviruses, and is a plausible intermediate host between humans and bats:

Awwww, come on, you can’t stay mad at this little guy.

Awwww, come on, you can’t stay mad at this little guy.

China said this rumor was false and refused to release any information. Scientists were finally able to confirm the existence of the raccoon-dog shop in the funniest possible way: a virologist had visited Wuhan in 2014, saw the awful conditions in the shop, and took a picture as an example of the kind of place that a future pandemic might start.

Source: NPR. To be fair, we have only the scientist’s word that this is why he had the picture. But he definitely did have it.

Source: NPR. To be fair, we have only the scientist’s word that this is why he had the picture. But he definitely did have it.

People say it would be a surprising coincidence if a zoonotic coronavirus pandemic just so happened to start in a city with a big coronavirus research lab, and this is true. But it would be an even more surprising coincidence if a lab-leak coronavirus pandemic just so happened to first get detected at a raccoon-dog stall in a wet market!

Saar: It’s not clear that the first case was at the wet market; a certain Mr. Chen, with no connection to the market, seems to have fallen sick on December 8. An SCMP article suggested there were 92 previously-undetected cases suspicious for COVID as far back as November. And even if half of the first forty universally-agreed-upon cases had market connections that means another half didn’t.

There was a bias towards detecting cases at the market: because authorities thought the market was the origin, and because everyone was thinking about zoonosis after SARS1, they only screened/diagnosed people with a market connection. One of the few non-market-connected COVID cases detected during this period was only detected because he was the relative of a hospital worker; the worker noticed the signs and insisted they go to the hospital despite the lack of a wet market connection.

Although the map of positive samples and cases at the market was centered near the raccoon-dog stall, that could be because that area was sampled more; it’s also close to the mahjong room, where visitors and vendors at the market would go and unwind in a tight, poorly ventilated area.

The next session will focus more on the WIV, but the short version is that they were doing lots of gain of function research. So one story compatible with the evidence is that a worker at WIV got infected with their modified coronavirus and passed it to his contacts. COVID started spreading quietly a few weeks to months before the first market-related case was detected. This accounts for the 92 earlier cases, Mr. Chen’s case, and the half of officially-detected cases with no wet market association. Then an infected person went to the market, causing a super-spreader event. Some of the infected market patrons went to the hospital, where doctors traced it back to the market and told other doctors to be on the lookout for wet market patrons coming in with weird viral pneumonias. They found some, declared victory, and the few anomalies - like the hospital worker’s relative - were forgotten, or assumed to have wet market connections that nobody could find. China quashed all evidence of the lab research (as was done in previous lab leak cases, eg the USSR) so all we have is the apparent wet market links that Peter found so convincing.

Peter: The supposed pre-wet-market cases are confirmed fakes.

Yes, the WHO did an investigation of whether there might have been COVID cases circulating before the wet market, and identified 92 unusual pneumonias that merited further review. But their final investigation, which included testing samples from these people after good tests became available, found that none of these people really had COVID.

As for Mr. Chen, he said in an interview that he was hospitalized for dental issues on December 8, caught COVID in the hospital on December 16, and then was erroneously reported as “hospitalized for COVID on December 8”. The December 16 date is after the first wet market cases.

Further, it seems epidemiologically impossible for COVID to have been circulating much before the first cases were officially detected December 11. The COVID pandemic doubles every 3.5 days. So if the first infection was much earlier - let’s say November 11 - we would expect 256x as much COVID as we actually saw. Even if the first couple of cases were missed because nobody was looking for them, the number of hospitalizations, deaths, etc, in January or whenever were all consistent with the number of people you’d expect if the pandemic started in early December - and not consistent with 256x that many people.

So probably we should just accept that the first reported case - a wet market vendor, December 11 - was very early in the pandemic. She wasn’t literally the first case - that would most likely have been someone who worked at the raccoon-dog shop, whose case might (like 95% of COVID cases) have been mild enough not to come to medical attention. But she was certainly very early.

Although authorities eventually decided COVID spread through a wet market and started deliberately looking for wet market connections, this only happened on December 30. So the earliest cases - including the 40 very earliest cases where half came from the wet market - weren’t biased (at least not through that particular route). So the claim that “the first case, and half of the first 40 cases, had wet market connections” stands as real and convincing evidence.

Although the exact center of the map of positive COVID samples in the wet market was the mahjong room, the samples taken from the mahjong room were not, themselves, positive (cf: although a low-resolution population density map of New York might show Central Park in the exact center of the population density gradient, Central Park does not itself have population).

There was no real “super-spreader event” at the wet market. There was a slow burn - one case the first day, a few more the next day, a few more the day after that. It’s hard to see how a single visit from an infected lab worker could do that.

So the only way it could possibly be a lab leak is if the lab leaked sometime in late November, infected exactly one lab worker, that worker went straight to the wet market, infected a vendor, then went home, quarantined, recovered, and all other cases were downstream of that first infected wet market vendor. This is unparsimonious.

Saar: The only source saying that Mr. Chen got sick early was an anonymous interview. And even if he was later than the first wet market cases, nobody was able to find any wet market connections. This means that whoever infected him was earlier than the index case and not linked to the wet market.

Peter argued that COVID couldn’t have been more than a few weeks old when the first wet market cases were detected. But this was based on its known doubling rate. If pre-discovery COVID had a slower doubling time than known COVID, it could have been around longer. And post-lockdown serology suggested numbers that were larger than claimed at the time. So contra Peter’s claims, the infection could have been going on longer, which wouldn’t require the first lab worker to go straight to the market. It could have been weeks.

Dr. Jesse Bloom’s investigation of the wet market samples, considered the final and most conclusive, failed to find a clear connection between COVID and raccoon-dogs or any other animals. Although the concentration of positive samples seemed highest near the raccoon dog stall, if you do a formal statistical analysis of which animals’ DNA was found near COVID samples most often, raccoon dogs are near the bottom. The top is wide-mouth bass, which can’t get COVID. This is obviously contamination, probably from infected humans touching wide-mouth bass tanks or something.

Although the Chinese data included a negative sample from a mahjong table, it included a mention of poultry being sold nearby, which might mean this wasn’t the mahjong room itself, but some other mahjong table at a poultry shop elsewhere in the market, and (dry) mahjong tables might not hold the virus well anyway.

Peter: Raccoon-dogs were sold in various cages at various stalls, separated by air gaps big enough to present a challenge for COVID transmission, and there’s no reason to think that one raccoon-dog would automatically pass it to all the others. The statistical analysis just proves there were many raccoon-dogs who didn’t have COVID. But you only need one. The raccoon dog shop and the drain leading out of the raccoon dog shop had some of the highest positive sample rates, which is more interesting than a statistical analysis which everyone agrees must be wrong (since it favors bass).

It’s unclear why the negative mahjong sample says something about poultry, but based on the stated location, it’s definitely the one in the mahjong room.

Session 1.5: Lineages

This was technically part of Session 2, but formed enough of a discrete topic that I found it confusing to intermix it with all the other viral genetics points. I’m spinning it out into a separate summary, but the videos are all in the next session.

Yuri: The coronavirus eventually mutated into many different strains. But the first big split, seen in some of the earliest samples, is between two different sub-strains called Lineage A and Lineage B, which differ by two mutations. In these two mutations, Lineage A is the same as BANAL-52, a bat virus which is the closest-known relative of COVID, but Lineage B is different. Since COVID probably evolved from something like BANAL-52, Lineage A must have come first, spread for a while, and then gotten two new mutations, turning it into Lineage B.

All of the cases at the wet market, including the first detected case, were Lineage B. Lineage A wasn’t discovered until about a week later, and none of the Lineage A patients had been to the wet market.

Lineage A (left) was used by the Minoan Cretans, but has never been deciphered. Lineage B (right) was used by the Mycaeneans for lists of palace goods.

Lineage A (left) was used by the Minoan Cretans, but has never been deciphered. Lineage B (right) was used by the Mycaeneans for lists of palace goods.

This matches Saar’s story above. The lab leaked to somewhere else in Wuhan, not the wet market. The virus spread undetected in the population for a while. During this time, it mutated to Lineage B. Then one of the people with Lineage B went to the wet market and started a superspreader event. The authorities sampled the patients, found Lineage B, then started looking elsewhere. Later they detected some of the earlier Lineage A cases.

The market is unlikely to be the origin of the pandemic, because the original Lineage A strain wasn’t found there.

Peter: Although Lineage A is evolutionarily older, Lineage B started spreading in humans first.

We know this because Lineage B is more common. Throughout the early pandemic, until the D614G variant drove all other strains extinct, a consistent 2/3 of the cases were B, compared to 1/3 A. Both strains spread at the same rate, so the best explanation is that B started earlier than A. Since COVID doubles every 3-4 days, probably Lineage B started 3-4 days earlier than Lineage A, which explains why it’s always been twice as many cases.

But also, Lineage B also has more internal genetic diversity than Lineage A. In general, older viruses have more genetic diversity (the “molecular clock”). This is further evidence that B started spreading first. Pekar 2022 and Pipes 2021 do analyses with known parameters for spread rate and diversity, and find 90%+ odds that Lineage B was the first one in humans.

Why did the older strain start spreading later? Probably the virus crossed from bats into raccoon-dogs on some raccoon-dog farm out in the country. It spread in the raccoon-dogs for a while, racking up mutations, including the (less mutated) Lineage A strain and the (slightly more mutated) Lineage B strain. Then several raccoon-dogs were taken to Wuhan for sale, including one with Lineage A and another with Lineage B. The one with Lineage B passed its virus to humans earlier. Then 3-4 days later, the Lineage A one passed its virus to humans.

Lineage A was first found in a Wuhan neighborhood right next to the wet market (closer to the wet market than 97% of Wuhan’s population). Again, it would be a bizarre coincidence if a lab leak pandemic was first detected at a wet market. But it would be an even more bizarre coincidence if a lab leak pandemic separated into two strains, and both were first detected at a wet market!

Although no known wet market cases were Lineage A, a positive Lineage A environmental sample was found at the wet market, and everyone agrees most cases went undetected. So maybe the Lineage B raccoon-dog spread its virus to a vendor, and that sub-strain mostly stayed in the market. But the Lineage A raccoon-dog spread its virus to a customer, who went back to his house nearby, and that strain spread in the neighborhoods next to the market.

This is the only story that explains the evolutionary precedence of A, the greater spread and older molecular clock of B, and the fact that both strains were first found very close to the wet market.

Yuri/Saar: Lineage B could be more common and diverse because it got the advantage of a super-spreader event in the wet market.

There are a few scattered cases of intermediates between A and B, and a few other scattered cases of lineages that seem even more ancestral (ie closer to the bat virus) than either. This doesn’t make sense in a double spillover hypothesis. But it does make sense if the lineages separated in human transmission somewhere between the lab and the first super-spreader event at the wet market.

Peter: Again, the wet market wasn’t a super-spreader event. COVID spread in the wet market at exactly its normal spread rate, doubling about once every 3.5 days. Stop calling the wet market a super-spreader event.

The scattered cases of “intermediates” are sequencing errors. They were all found by the same computer software, which “autofills” unsequenced bases in a genome to the most plausible guess. Because Lineage B was already in the software, depending on which part of a Lineage A virus you sequenced, you might get one half or the other autofilled as Lineage B, which looked like an “intermediate”. We know this because all the supposed “intermediates” were partial cases sequenced by this particular software. We can confirm this by noting that there are too many intermediates! That is, where Lineage A is (T/C) and Lineage B is (C/T), the software found both (T/T) “intermediates” and (C/C) “intermediates”. But obviously there can only be one real intermediate form, and we have to dismiss one or the other. But in fact we can dismiss both, because they were both caused by the same software bug.

The scattered “progenitor” cases - those closer to the ancestral bat virus than either A or B - are reversions, ie cases where a new mutation in the virus happened to hit an already-mutated base and shift it back towards the ancestral virus. We know this because all of these “progenitors” were scattered cases found months after the pandemic started, often in entirely different countries from Wuhan. If these were real progenitor viruses, they would have either fizzled out or exploded into a substantial portion of all cases, not be found one time in one guy in Malaysia. Given the number of mutations the virus developed over the course of the pandemic, it’s inevitable that some of them would be mutations that bring it closer to the original bat virus, and in fact we find the number of “progenitors” found very nicely matches the number of progenitor-appearing viruses we would expect by chance. And in many cases, we know the “progenitors” are newer than the original lineages, because they also have some of the later mutations that Lineage A or B picked up along the way, alongside their apparent ancestral-bat-virus-like mutations.

Session 2: Viral Genetics

Yuri: Two years before COVID, scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, together with colleagues at the University of North Carolina, sent in a grant proposal for the DEFUSE program. This program, intended to locate and better understand potential future pandemic viruses, involved going into bat caves and collecting new coronaviruses. Once they had them, they would do gain-of-function: specifically, they would add a furin cleavage site to make them more infectious and see what happened.

(quick interlude: COVID’s spike protein has two sections: one binds to human cells through the ACE2 receptor, the other helps fuse with the cell after binding. In order to avoid the immune system, it hides both of these into one spike. But when it reaches a cell, it needs to separate them again. It takes advantage of a human respiratory enzyme, furin, to do the separation - this also ensures that it only infects its primary target, human respiratory cells. The part of COVID that lets it get separated by furin is called the “furin cleavage site”. COVID’s bat-virus ancestors were gastrointestinal viruses; the addition of a furin cleavage site was what made them respiratory viruses.)

We’ve found two close relatives of COVID: bat viruses called RATG-13 and BANAL-52. In particular, COVID looks more or less like BANAL-52 plus a furin cleavage site.

There are 1500 sarbecoviruses, members of the family of viruses that includes SARS and SARS2/COVID. None of them except COVID have furin cleavage sites. BANAL-52, COVID’s closest ancestor, doesn’t even have anything resembling one that could mutate into a functional furin cleavage site like COVID’s.

Instead, COVID - which mostly just resembles BANAL-52 with a few scattered single-point mutations - has twelve completely new nucleotides in a row - a fully formed furin cleavage site that came out of nowhere. There is nowhere else in the genome that COVID differs from BANAL-52 in such a profound way. It’s just BANAL-52 plus a little bit of random mutation plus a fully-formed furin cleavage site that came out of nowhere.

Further, the furin cleavage site is weird. It uses the protein arginine twice. But instead of the nucleotides coding for arginine in the usual viral way, both times it uses the codons CGG - the way that higher animals code for arginine. This works fine - it’s just not how viruses do it.

So the obvious conclusion is that WIV, which said in 2018 that it was going to find viruses and add furin cleavage sites to them, found a close relative of BANAL-52 and added a furin cleavage site. Since they were humans, and most familiar with the human way of encoding arginine, they added it as CGG both times.

COVID seemed surprisingly optimized for infecting humans. Of fifty animals it was tested in, including the usual coronavirus intermediate hosts (pangolins, raccoon-dogs, etc), it was best at infecting human cells. Further, a virus that enters a new species will usually show a burst of mutations as it “figures out” the best way to adapt to that species’ unique biology. But COVID has had a pretty constant mutation rate in humans, from the beginning of the pandemic to the end. That suggests it was already adapted to humans. This could be because the lab screened for viruses with existing adaptations, because they passed it through humanized mice in the lab, or because it adapted in the hundreds of undetected cases that happened between the lab and detection in the wet market.

Usually, research with potentially dangerous coronaviruses is done in BSL-3 or 4, ie high to very-high security. But WIV was irresponsibly doing it in BSL-2, ie medium security. The researchers weren’t even required to wear masks. In general, about 1/500 labs will leak any given pathogen they’re working on (?!). But because WIV was researching such an infectious virus in such an irresponsible way, the odds of a leak were much higher.

The most likely explanation for all these facts is that WIV went ahead and did the gain-of-function research they said they were going to do (the particular DEFUSE grant proposal we know about got rejected, but it proves that Wuhan wanted to do this, and they could easily have gotten funding somewhere else, or done it out of their regular budget). They found a close relative of BANAL-52 and added a furin cleavage site as a simple twelve-nucleotide insertion, using the human method of encoding arginine that their genetic engineers were familiar with. Then it leaked, spread for a while in the general Wuhan population, and eventually made it to the wet market where it got detected.

Peter: As mentioned earlier, the DEFUSE grant was rejected. Further, the grant said that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was responsible for finding the viruses, and the University of North Carolina would do all the gain-of-function research. This was a reasonable division of labor, since UNC was actually good at gain-of-function research, and WIV mostly wasn’t. They had done a few very simple gain-of-function projects before, but weren’t really set up for this particular proposal and were happy to leave it for their American colleagues.

Even if WIV did try to create COVID, they couldn’t have. As Yuri said, COVID looks like BANAL-52 plus a furin cleavage site. But WIV didn’t have BANAL-52. It wasn’t discovered until after the COVID pandemic started, when scientists scoured the area for potential COVID relatives. WIV had a more distant COVID relative, RATG-13. But you can’t create COVID from RATG-13; they’re too different. You would need BANAL-52, or some as-yet-undiscovered extremely close relative. WIV had neither.

Are we sure they had neither? Yes. Remember, WIV’s whole job was looking for new coronaviruses. They published lists of which ones they had found pretty regularly. They published their last list in mid-2019, just a few months before the pandemic. Although lab leak proponents claimed these lists showed weird discrepancies, this was just their inability to keep names consistent, and all the lists showed basically the same viruses (plus a few extra on the later ones, as they kept discovering more). The lists didn’t include BANAL-52 or any other suitable COVID relatives - only RATG-13, which isn’t close enough to work.

Could they have been keeping their discovery of BANAL-52 secret? No. Pre-pandemic, there was nothing interesting about it; our understanding of virology wasn’t good enough to point this out as a potential pandemic candidate. WIV did its gain-of-function research openly and proudly (before the pandemic, gain-of-function wasn’t as unpopular as it is now) so it’s not like they wanted to keep it secret because they might gain-of-function it later. Their lists very clearly showed they had no virus they could create COVID from, and they had no reason to hide it if they did.

COVID’s furin cleavage site is admittedly unusual. But it’s unusual in a way that looks natural rather than man-made. Labs don’t usually add furin cleavage sites through nucleotide insertions (they usually mutate what’s already there). On the other hand, viruses get weird insertions of 12+ nucleotides in nature. For example, HKU1 is another emergent Chinese coronavirus that caused a small outbreak of pneumonia in 2004. It had a 15 nucleotide insertion right next to its furin cleavage site. Later strains of COVID got further 12 - 15 nucleotide insertions. Plenty of flus have 12 to 15 nucleotide insertions compared to other earlier flu strains.

Sometimes insertions happen because of a mistake in viral replication. Other times the virus gets confused between its own RNA and its host’s, and splices a bit of the host RNA into the virus. This would neatly explain why the insertion used the unusual coding CGG for arginine, which is common in animals but rare in viruses. On the other hand, it’s not that rare in viruses - COVID uses CGG for arginine about 3% of the time. And human engineers don’t necessarily use it any more than that - Peter was able to find one example of humans adding arginine to a virus, and 0 out of the 5 arginines added were CGG.

COVID’s furin cleavage site is a mess. When humans are inserting furin cleavage sites into viruses for gain-of-function, the standard practice is RRKR, a very nice and simple furin cleavage site which works well. COVID uses PRRAR, a bizarre furin cleavage site which no human has ever used before, and which virologists expected to work poorly. They later found that an adjacent part of COVID’s genome twisted the protein in an unusual way that allowed PRRAR to be a viable furin cleavage site, but this discovery took a lot of computer power, and was only made after COVID became important. The Wuhan virologists supposedly doing gain-of-function research on COVID shouldn’t have known this would work. Why didn’t they just use the standard RRKR site, which would have worked better? Everyone thinks it works better! Even the virus eventually decided it worked better - sometime during the course of the pandemic, it mutated away from its weird PRRAR furin cleavage site towards a more normal form.

Further, COVID’s furin cleavage site was inserted via what seems to be a frameshift mutation - it wasn’t a clean insertion of the amino acids that formed the site, it was an insertion of a sequence which changed the context of the surrounding nucleotides into the amino acids that formed the site. This is a pointless too-clever-by-half “flourish” that there would be no reason for a human engineer to do. But it’s exactly the kind of weird thing that happens in the random chance of evolution.

COVID is hard to culture. If you culture it in most standard media or animals, it will quickly develop characteristic mutations. But the original Wuhan strains didn’t have these mutations. The only ways to culture it without mutations are in human airway cells, or (apparently) in live raccoon-dogs. Getting human airway cells requires a donor (ie someone who donates their body to science), and Wuhan had never done this before (it was one of the technologies only used at the superior North Carolina site). As for raccoon-dogs, it sure does seems suspicious that the virus is already suited to them.

The claim that COVID is uniquely adapted to humans is false. The paper that claimed that defined how well COVID was adapted to different animals by those animals’ difference (on the relevant cell receptors) from humans. So in its methodology, humans came out #1 by default. If you don’t do that, COVID is better-adapted to many other animals.

It’s not necessarily true that viruses see a burst of mutations when they enter a new host. COVID spread to deer and mink, and in neither case was there a burst of mutations. COVID has a pretty simple job of infecting respiratory cells and is already very good at it, regardless of species.

In Yuri’s model, Wuhan Institute of Virology picked up a discarded grant and decided to do the gain-of-function half allotted to a different university, despite their relative inexperience. They skipped over all the SARS-like viruses they were supposed to work on, and all the standard gain-of-function model backbones, in favor of BANAL-52, a virus which would not be discovered for another two years, but which they somehow had samples of, which they had for some reason decided to keep secret despite its total lack of interestingness. Then they would have had to eschew all usual gain-of-function practices in favor of inserting a weird furin cleavage site that shouldn’t have worked according to the theory they had at the time, via a frameshift mutation. Then they would have had to culture it, a technique beyond their limited capabilities. Then it would have had to leak, and magically show up again in front of the raccoon-dog stall at a wet market.

Yuri: WIV wouldn’t have needed to keep BANAL-52 “secret” in some kind of sinister way. Plenty of researchers have backlogs of work they haven’t published yet. Probably they a found BANAL relative in one of their normal sampling trips, did some preliminary studies on it, and planned to publish it later once they cleaned up their data. Everyone works like this.

The part of DEFUSE saying that they would only work on viruses that were 95% similar to SARS is unclear and might mean something else. It looks more like they say they’ll start with those viruses, but also do some work on novel viruses. BANAL-52 could have been one of the novel viruses.

The furin cleavage site is weird, but the researchers might have done that on purpose, to make the virus easier to keep track of, or to test different furin cleavage sites. Depending on the exact BANAL-52 relative they used, it might not even be a frameshift; there’s a particular way to spell serine that would make the insertion more natural.

The claims that COVID can’t be cultured in normal media are based on speculative original research by Peter and might not hold up.

Peter: WIV did most of its virus-gathering in a trip to a Yunnan cave between 2010 and 2015. All those viruses have long since been processed and added to the database. There’s no sign that they made more trips to Yunnan caves, and no reason for them to keep that secret. So the idea that they might just have some new viruses they didn’t publish doesn’t hold up.

But suppose they did make more trips. Given the amount of time between the DEFUSE proposal and COVID, if they kept to their normal virus-collection rate, they would have gotten about thirty new viruses. What’s the chance that one of those was BANAL-52? There are thousands of bat viruses, and BANAL-52 is so rare that it wasn’t found until well after the pandemic started and people were looking for it very hard. So the chance that one of their 30 would be BANAL-52 is low. Also, they said in DEFUSE that they planned to go back to the same Yunnan cave. But BANAL-52 was found far away from that cave, so unless it ranged over a wide area, they probably couldn’t have found it even if they got very lucky.

Session 3: Closing Arguments

This third debate was supposed to be about “inference”, ie how much Bayesian evidence was provided by each of the facts given so far, and how to fit them into the Rootclaim probabilistic model. I’m going to relegate my summary of the more probabilistic half to the next section of this post, and just include the closing arguments here.

Saar: Peter’s case hinges on the idea that it’s very improbable that a lab leak pandemic would first show up at a wet market. But this isn’t necessarily improbable. The Huanan Seafood Market had several factors that made it a likely location for a superspreader event. It was busy, with over 10,000 visitors a day. Many of the people there (eg the 1,000 vendors) came back daily, letting them reinfect each other. It had poor ventilation, especially in the high-positivity area near the raccoon-dog stall. It had cold wet surfaces on which the virus could survive for long periods. It was indoors, which prevented UV light from killing the virus. Given a small amount of sporadic COVID going around Wuhan, it’s not surprising for the first place it started spreading en masse to be a wet market.

In fact, we have several examples of this. When China was COVID Zero, there would occasionally be small outbreaks that the authorities would have to contain. Most of these were at wet markets. For example, the big COVID outbreak in Beijing started at Xinfadi Market, their local seafood market. This couldn’t be an animal spillover, because there were no raccoon-dogs or other weird wildlife there. So it must be that wet markets are natural places for superspreader events. There are several other examples, which make up about half of the total outbreaks in Zero COVID era China, plus others in Singapore and Thailand. Since COVID clusters concentrate in wet markets even when there is no animal spillover, we should accept this as a property of the virus, and not attribute any significance to the fact that this happened in Wuhan too.

Peter: About 1/10,000 citizens of Wuhan was a wet market vendor. So there’s a 1/10,000 chance that the first known COVID case should be a wet market vendor by chance alone. Weibo lists the most popular places for people to check in to their network on their phones, and the wet market was the 1600th most popular place in Wuhan, meaning that if you weight locations by busy-ness, there’s a less than 1/1600 chance that the first cases would be in the wet market.

Yes, the wet market is indoors, has mediocre ventilation, has repeat visitors, etc. So do thousands of other places in Wuhan, like schools, hospitals, workplaces, places of worship. The wet market isn’t special in any way. And again, it wasn’t a superspreader event! COVID spread at the same rate in the wet market as it does everywhere else: doubling once per 3.5 days. It doesn’t matter what kinds of arguments you can come up with for why the wet market should have been the perfect superspreader event location, we can look at it and see that it wasn’t. It’s an environment that spreads COVID at exactly the normal rate.

Zero COVID era Chinese outbreaks were concentrated in wet markets because they received infected animal products. We know why there was an outbreak in the Xinfadi Market in Beijing: it was because the seafood stall got frozen fish from some non-Zero-COVID country, the fish had COVID particles on it, and the vendor got infected and spread it to everyone else. Something like this is true for the other Chinese wet market based outbreaks we know about it. So this makes the opposite point you think it does: wet markets start outbreaks because there are infected goods being sold there. Then the virus spreads through the wet market at a completely normal rate.

Saar: The Weibo list of 1600 places bigger than the wet market is likely inaccurate, because it’s based on check-in data and people don’t check in to seafood markets. Most of those 1600 places aren’t amenable to superspread. The 70 markets supposedly bigger than Huanan are irrelevant, because they’re supermarkets, open air markets, etc. Huanan is the largest seafood market in central China, and a more likely place for the first cluster of cases to be noticed.

Markets weren’t a common spillover location in SARS1, so the zoonosis hypothesis hasn’t “called” this event in a way that should give them a high Bayes factor.

And there’s still plenty of evidence for isolated (though not super-spreading) pre-market cases. A British expatriate in Wuhan, Connor Reed, says he got sick in November, three weeks before the first wet market case. Later the hospital tested his samples and said it was COVID. Another paper reports 90 cases before the first wet market one.

Peter: Connor Reed was lying. The case wasn’t reported in any peer-reviewed paper. It was reported in the tabloid The Daily Mail , months after it supposedly happened. He also told the Mail that his cat died of coronavirus too, which is rare-to-impossible. Also, to get a positive hospital test, he would have had to go to the hospital, but he was 25 years old and almost no 25-year-olds go to the hospital for coronavirus. His only evidence that it was COVID was that two months later, the hospital supposedly “notified” him that it was. The hospital never informed anyone else of this extremely surprising fact which would be the biggest scientific story of the year if true. So probably he was lying. Incidentally, he died of a drug overdose shortly after giving the Mail that story; while not all drug addicts are liars, given all the other implausibilities in his story, this certainly doesn’t make him seem more credible. And in any case, he claimed he got his case at a market “like in the media”

The other 90 cases are also fake. A lab leak guy found a paper that mentioned 90 more cases than other papers, and made up a conspiracy theory where the author was trying to secretly communicate that there had been 90 secret cases before any of the confirmed cases, even though there was nothing about this in the text of the paper. But actually that paper just counted cases differently than other papers, and they were referring to normal cases after the pandemic officially started.

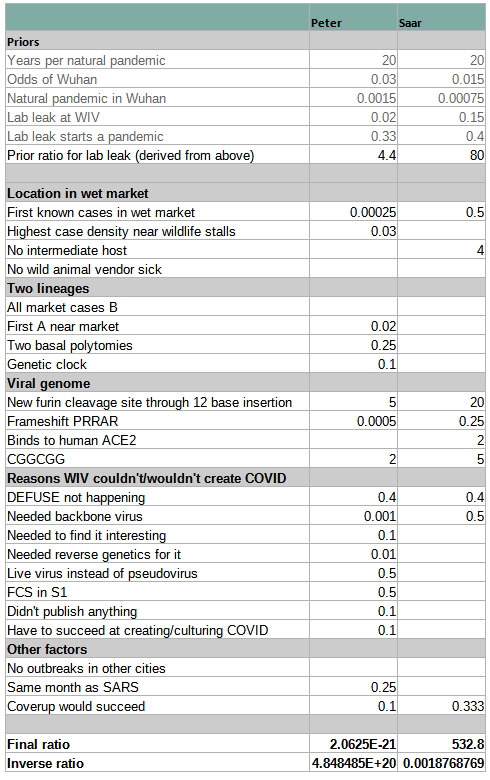

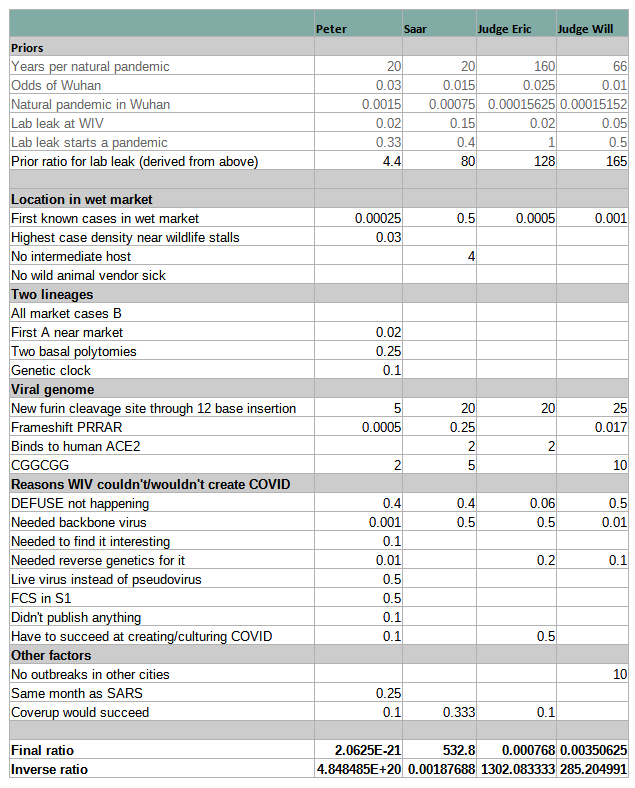

Again, I’ll come back to the discussion about inference later, but for now, here’s a table of both sides’ reasoning. This exact presentation comparing both analyses is mine3, but you can see Saar’s version here, and Peter’s starting at 45:33 of this video.

Slightly made up; the two sides didn’t express their probabilities in the same way and I had to make editorial decisions to match them. Note that these aren’t entirely comparable because Peter is being laxer about out-of-model probability than Saar. Although Saar’s final odds here are 533-to-1, this just the central estimate. Rootclaim’s real final probability is 94% lab leak. You can see their analysis here.

Slightly made up; the two sides didn’t express their probabilities in the same way and I had to make editorial decisions to match them. Note that these aren’t entirely comparable because Peter is being laxer about out-of-model probability than Saar. Although Saar’s final odds here are 533-to-1, this just the central estimate. Rootclaim’s real final probability is 94% lab leak. You can see their analysis here.

And The Winner Is . . .

…

…

…

…

…

Peter and the zoonosis hypothesis.

This was a decisive victory. There were two judges, who each gave separate verdicts (or were allowed to declare a draw). Both judges decided in favor of Peter.

You can see the judges’ own summary of their reasoning here (Will, Eric)

Manifold agreed with the judges. There was a prediction market on who would win. It started out 70-30 in favor of lab leak. As the videos came out, zoonosis started doing better and better. I don’t want to take the exact final numbers too seriously, since I think some of the later price increases involved hints from the participants’ behavior. But it’s clear which way viewers thought the wind was blowing4.

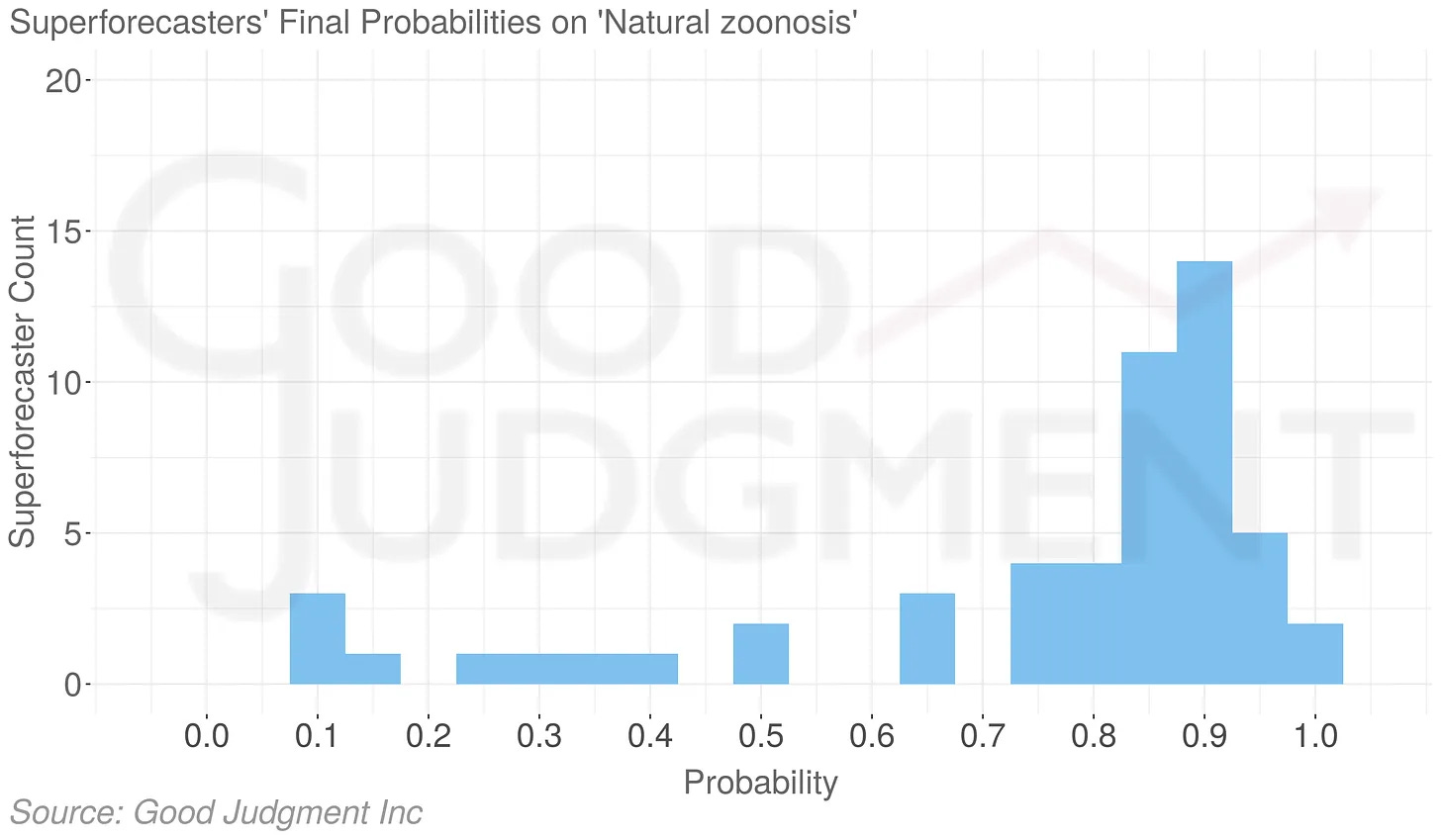

Around the same time, the Good Judgment Project - Philip Tetlock’s group studying superforecasters - put out a report on the lab leak hypothesis. After studying it in depth, his forecasters ended up 75-25 in favor of zoonosis. The Rootclaim debate was one of ten sources they said they found especially interesting.

And also around the same time, and unrelated to any of this, the Global Catastrophic Risks Institute surveyed experts (“168 virologists, infectious disease epidemiologists, and other scientists from 47 countries”) and found the same thing (though see here for some potential problems with the survey):

For what it’s worth, I was close to 50-50 before the debate, and now I’m 90-10 in favor of zoonosis.

III. The Math And The Aftermath

The third debate session was about “inference”, how to put evidence together. I put this part off until after disclosing the winner, because I wanted to talk about some of these issues at more length.

The Math: Judges

Both judges included a probabilistic analysis in their written decision. Here’s the same table as above, expanded to add the judges:

I shoehorned the judges’ factors into the categories I already had; some of them were actually subtly different from Peter’s, Saar’s, and each other’s. The “priors” category is especially a mess here.

I shoehorned the judges’ factors into the categories I already had; some of them were actually subtly different from Peter’s, Saar’s, and each other’s. The “priors” category is especially a mess here.

We’ll go over these later, but I get the impression that they both thought of probabilistic analyses as an afterthought. For example, Judge Eric wrote 30,000 words about which considerations moved him, and only then includes the analysis, saying:

I am not convinced that this Bayesian calculation is even an appropriate way to estimate the relative posterior probability of Z and LL; it just seemed fair that after criticizing Rootclaim’s calculations at length I should make an attempt at it myself.

Judge Will’s decision ran to 10,000 words. He said he independently tried both reasoning it out intuitively, and running the Bayesian analysis, and was relieved when these two methods returned the same result. He said:

I am skeptical that the Bayesian decision making/evaluation methods are any more “objective” than [intuitive reasoning]. I think they maximize legibility, not objectivity, and tend to hide the intuitive/heuristic portion in the data inclusion step and values, where it’s harder to see . . . I am not skilled in the Bayesian method, and I am sure I made significant mistakes. More time and practice would improve and refine my estimates. At the fundamental rules of the universe level, Bayesian analysis must be the best way to evaluate evidence. However, I am unsure that it’s a good strategy for a human given our cognitive limitations, and doubly unsure it’s truly being used (in the dispassionate sense) where the outcome is social desirability/fame/Twitter likes.

I’m focusing on this because Saar’s opinion is that the debate went wrong (for his side) because he didn’t realize the judges were going to use Bayesian math, they did the math wrong (because Saar hadn’t done enough work explaining how to do it right), and so they got the wrong answer. I want to discuss the math errors he thinks the judges made, but this discussion would be incomplete without mentioning that the judges themselves say the numbers were only a supplement for their intuitive reasoning.

That having been said, let’s look deeper into some of Saar’s concerns.

The Math: Extreme Odds

Saar complained that Peter’s odds were too extreme. For example, Peter said there was only a 1/10,000 chance that a lab leak pandemic would first show up at a wet market.

Peter’s argument went something like: obviously a zoonotic pandemic would start at a site selling weird animals. But a lab leak pandemic - if it didn’t start at the lab - could show up anywhere. 1/10,000 Wuhan citizens work at the wet market. So if a lab leak was going to show up somewhere random, the wet market was a 1/10,000 chance.

Saar had specific arguments against this, but he also had a more general argument: you should rarely see odds like 1/10,000 outside of well-understood domains. In his blog post, he gave this example:

A prosecutor shows the court a statistical analysis of which DNA markers matched the defendant and their prevalence, arriving at a 1E-9 probability they would all match a random person, implying a Bayes factor near 1E9 for guilty.

But if we try to estimate p(DNA ~guilty) by truly assuming innocence, it is immediately evident how ridiculous it is to claim only 1 out of a billion innocent suspects will have a DNA match to the crime scene. There are obviously far better explanations like a lab mistake, framing, an object of the suspect being brought by someone to the scene, etc.

| So the real p(wet market | lab leak) isn’t the 1/10,000 chance a pandemic arising in a random place hits the wet market, but the (higher?) probability that there’s something wrong with Peter’s argument. |

Then Saar tried to show specific things that might be wrong with Peter’s argument. I didn’t find his specific examples convincing. But maybe the question shouldn’t be whether I agreed with him. It should be whether I’m so confident he’s wrong that I would give it 10,000-to-1 odds.

This makes total sense, it’s absolutely true, and I want to be really, really careful with it. If you take this kind of reasoning too far, you can convince yourself that the sun won’t rise tomorrow morning. All you have to do is propose 100 different reasons the sunrise might not happen. For example:

-

The sun might go nova.

-

An asteroid might hit the Earth, stopping its rotation.

-

An unexpected eclipse might blot out the sun.

-

God exists and wants to stop the sunrise for some reason.

-

This is a simulation, and the simulators will prevent the sunrise as a prank.

-

Aliens will destroy the sun.

…and so on until you reach 100. On the one hand, there are 100 of these reasons. But on the other, they’re each fantastically unlikely - let’s say 99.9999999999% chance each one doesn’t happen - so it doesn’t matter.

But suppose you get too humble. Sure, you might think you have a great model of how eclipses work and you know they never happen off schedule - but can you really be 99.9999999999% sure you understood your astronomy professor correctly? Can you be 99.9999999999% sure you’re not insane, and that your “reasoning” isn’t just random seizings of neurons that aren’t connecting to reality at any point? Seems like you can’t. So maybe you should lower your disbelief in each hypothesis to something more reasonable, like 99%. But now the chance that the sun rises tomorrow is 0.99^100, aka 36%. Seems bad.

Also, suppose I agree I shouldn’t use numbers like 1-in-10,000. What should my real numbers be? Saar says it’s the strength of the strongest hypothesis for why I might be wrong. But I can’t think of any good reasons I might be wrong here. Should I feel okay after adjusting it down to 1-in-1,000? 1-in-100? 1-in-10?

Saar said he “could have” argued that there was only a one-in-a-million chance COVID’s furin cleavage site evolved naturally. Instead, he gave a Bayes factor of 1-in-20, because he wanted to leave room for out-of-model error. But (as Saar understands it) the judges’ probabilistic analysis took Peter’s unadjusted 1-in-10,000 wet market claim seriously and Saar’s fully-adjusted 1-in-20 furin cleavage site claim literally, compared them, found Peter’s evidence stronger, and gave him the victory. You can see why he’s upset.

(again, the judges deny basing their verdict solely on the probabilistic models)

At some point you have to take your best guess about how confusing a given field is and how wrong you could be - how often do labs overstate their DNA results? How much do you know about how viruses get furin cleavage sites? How sure are you about the demographics of Wuhan? How tightly does your “there have been at least a million days without aliens destroying the sun, therefore aliens will not destroy the sun tomorrow” argument hang together? - and choose a number.

The Math: Extreme Odds, Part II

During the debate, Peter showed this slide:

Okay, this one is just awful.

It takes the risky gambit above - giving extreme odds to something - then doubles down on it by multiplying across twenty different stages to get a stupendously low probability of 1/5*10^25. If we believe this, it’s more likely that we win the lottery three times in a row than that we learn lab leak was true after all.

Eliezer Yudkowsky calls this the Multiple Stage Fallacy. Even aside from the failure mode in the sunrise example above (where people are too reluctant to give strong probabilities), it fails because people don’t think enough about the correlations between stages. For example, maybe there’s only 1/10 odds that the Wuhan scientists would choose the suboptimal RRAR furin cleavage site. And maybe there’s only 1/20 odds that they would add a proline in front to make it PRRAR. But are these really two separate forms of weirdness, such that we can multiply them together and get 1/200? Or are scientists who do one weird thing with a furin cleavage site more likely to do another? Mightn’t they be pursuing some general strategy of testing weird furin cleavage sites?

(For example, Yuri proposed that, because the scientists wanted to understand how pandemic coronaviruses originate in nature, they might deliberately pick more natural-looking features over more designed-looking ones, which would neatly explain many features seemingly inconsistent with lab leak. Is this a conspiracy theory? Rootclaim is able to successfully route around this question. If the probability of a feature happening in nature is X, then the probability of it happening in this variant of lab leak scenario is X * [chance that the scientists wanted to imitate nature). This gives it a (deserved) complexity penalty without ruling out this (non-zero and potentially important) possibility.)

In any case, Peter didn’t care as much about probabilistic analysis as Saar, he didn’t make his case hinge on this slide, and he might have been kind of using it to troll Rootclaim (which definitely worked). He might not have been making any of the mistakes above. But anyone who took this slide seriously would end up dramatically miscalibrated.

The Math: Big Pictures

Another of Saar’s concerns with the verdict was that Peter was an extraordinary debater, to the point where it could have overwhelmed the signal from the evidence.

It’s hard to watch the videos and not come away impressed. Peter seems to have a photographic memory for every detail of every study he’s ever read. He has some kind of 3D model in his brain of Wuhan, the wet market, and how all of its ventilation ducts and drains interacted with each other. Whenever someone challenged one of his points, he had a ten-slide PowerPoint presentation already made up to address that particular challenge, and would go over it with complete fluency, like he was reciting a memorized speech. I sometimes get accused of overdoing things, but I can’t imagine how many mutations it would take to make me even a fraction as competent as Peter was.

Saar’s closing argument included the admission:

Peter, I think everyone can agree, has much more knowledge on [COVID] origins than we do. He’s invested much more time. He may be a much more talented researcher. He’s much more into the details. He probably knows the best in the world on origins at this point.

Once you’ve described your opponent that way in your closing argument, what’s left of your case?

Saar thought a lot was left. Throughout the debate, he tried to make a point about how getting the inference right was more important than winning sub-sub-sub-debates about individual lines of evidence. Although Peter won most specific points of contention, Saar thought that if the judges could just keep their mind on the big picture, they would realize a lab leak was more likely.

I’m potentially sympathetic to arguments like Saar’s. Imagine a debate about UFOs. Imaginary-Saar says “UFOs can’t be real, because it doesn’t make sense for aliens to come to Earth, circle around a few fields in Kansas, then leave without providing any other evidence of their existence.” Imaginary-Peter says “John Smith of Topeka saw a UFO at 4:52 PM on 6/12/2010, and everyone agrees he’s an honorable person who wouldn’t lie, so what’s your explanation of that?” Saar says “I don’t know, maybe he was drunk or something?” Peter says “Ha, I’ve hacked his cell phone records and geolocated him to coordinates XYZ, which is a mosque. My analysis finds that he’s there on 99.5% of Islamic holy days, which proves he’s a very religious Muslim. And religious Muslims don’t drink! Your argument is invalid!” On the one hand, imaginary-Peter is very impressive and sure did shoot down Saar’s point. On the other, imaginary-Saar never really claimed to have a great explanation for this particular UFO sighting, and his argument doesn’t depend on it. Instead of debating whether Smith could or couldn’t have been drunk, we need to zoom out and realize that the aliens explanation makes no sense.

The problem was, Saar couldn’t effectively communicate what his big picture was. Neither deployed some kind of amazingly elegant prior. They both used the same kind of evidence. The only difference was that Peter’s evidence hung together, and Saar’s evidence fell apart on cross-examination.

I think - not because Saar really explained it, but just reading between the lines - Saar thought the un-ignorable big picture evidence was the origin in a city with a coronavirus gain-of-function lab, and the twelve-nucleotide insertion in the furin cleavage site.

To some degree, Peter just ate the loss on those questions. No matter how you slice it, it really is a weird coincidence that the epidemic started so close to Asia’s biggest coronavirus laboratory. Peter tried to deflect this - he pointed out there were other BSL-3 and BSL-4 laboratories in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, etc. But this was a rare question where he unambiguously came out looking worse - the other cities’ labs had much less coronavirus-specific research. Wuhan really was unique (aside from the other big coronavirus lab in North Carolina).

Peter did better when he tried to control the damage: there are a couple hundred million people in the South Asian areas where people eat weird animals exposed to virus-infected bats, Wuhan has a population of about 12 million, so maybe 1.5% of all potential zoonotic pandemics should start in Wuhan. Peter tried to argue that Wuhan was a local trade center, so maybe we should up that to 5 - 10%. 5 - 10% coincidences aren’t that rare. Even 1.5% coincidences happen sometimes.

Likewise, the furin cleavage site really does stand on a genetic map. I didn’t feel like either side did much math to quantify how weird it was. Naively, I might think of this as “30,000 bases in COVID, only one insertion, it’s in what’s obviously the most interesting place - sounds like 30,000-to-one odds against”. Against that, a virus with a boring insertion would never have become a pandemic, so maybe you need to multiply this by however much viral evolution is going on in weird caves in Laos, and then you would get the odds that at least one virus would have an insertion interesting enough to go global. Neither participant calculated this in a way that satisfied me (though see here for related discussion). Instead, Peter tried to undermine the furin argument by showing that, as surprising as the site was under a natural origin, it would be an even more surprising choice for human engineers. Saar argued it wasn’t - but because of his policy of giving adjusted-for-model-error odds, he only gave this a factor of 30 in his analysis. Since Peter gave it a higher factor of 50 in his analysis, it looked from the outside like Saar had already conceded this point, and the judges were mostly happy to go with Saar’s artificially-low estimate.

The Math: Double Coincidences

Saar brought up an interesting point halfway through the debate: you should rarely see high Bayes factors on both sides of an argument.

That is, suppose you accept that there’s only a 1-in-10,000 chance that the pandemic starts at a wet market under lab leak. And suppose you accept there’s only a 1-in-10,000 chance that COVID’s furin cleavage site could evolve naturally.

If lab leak is true, then you might find 1-in-10,000 evidence for lab leak. But it’s a freak coincidence that there was 1-in-10,000 evidence for zoonosis5.

Likewise, if zoonosis is true, you might find 1-in-10,000 evidence for this true thing. But it’s a freak coincidence that there was 1-in-10,000 evidence for lab leak.

Either way, you’re accepting that a 1-in-10,000 freak coincidence happened. Isn’t it more likely you’ve bungled your analysis?

I was following along at home, and I definitely bungled this point; I had some high Bayes factors on both sides. I adjusted some of them downward based on Saar’s good point, but how far should we take it?

Here I remember The Pyramid And The Garden: you can get very strong coincidences if you have many degrees of freedom, ie buy a lot of lottery tickets. So for example, suppose there are fifty things about a virus. You should expect at least one of those to have a one-in-fifty coincidence by pure chance.

What about more than that? You might be able to get away with this by saying there are an infinite number of possible conspiracy theories, and some from that infinite set are brought into existence when a strong enough coincidence makes them plausible. For example, it’s really weird that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. If I wanted, I could form a conspiracy theory about a group of weird assassins obsessed with killing Founding Fathers on important dates, and then Jefferson and Adams’ deaths would be 1/10,000 evidence for that theory. But this is the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy, which Saar warned against several times.

I don’t know if “the virus started in Wuhan, which is where they’re doing this research” gets a Texas Sharpshooter penalty, or how high that penalty should be. But the furin cleavage site doesn’t - people were talking about lab leak before anyone noticed it.

The Aftermath: Peter

Peter seemed satisfied with the result, in an understated sort of way:

It seemed like an interesting experiment in monetizing the debunking of a conspiracy theory. I think there’s usually a big asymmetry where it’s easy to get rich spreading bullshit (like, the top anti-vaxxers during the pandemic all made a million dollars a year on substack), but it’s almost impossible to make money on debunking it. The Rootclaim challenge seemed like one rare case where the opposite was true.

Beyond that, I don’t know what it’s good for. It does seem like there could be a positive social impact from more people understanding that the lab leak hypothesis is (almost certainly) false.

The Aftermath: Saar

Saar says the debate didn’t change his mind. In fact, by the end of the debate, Rootclaim released an updated analysis that placed an even higher probability on lab leak than when they started.

In his blog post, he discussed the issues above, and said the judges had erred in not considering them. He respects the judges, he appreciates their efforts, he just thinks they got it wrong. Although he respected their decision, he wanted the judges to correct what he saw as mistakes in their published statements, which delayed the public verdict and which which Viewers Like You did not appreciate:

I ran an early draft of this post by him. There was some miscommunication about the exact publication date, so he hasn’t had time to write up a full response, but he has some quick thoughts (and I’ll link the full response when he writes it). He says:

We will provide a full response to this post soon, but the main problem with it is fairly simple:

There is general agreement that the main evidence for zoonosis is HSM (Huanan Seafood Market) forming an early cluster of cases. The contention is whether it is amazing 10,000x evidence, or is it negligible. All other evidence points to a lab leak, and if HSM is shown to be weak, lab leak is a clear winner.

We provided an analysis of why it is negligible that is as close to mathematical proof as such things can be. Read it here.

Scott and I exchanged a few emails on this issue and Scott preferred to discuss more intuitive analyses of HSM, using rules of thumb that likely served him well in the past.

While I believe I managed to mostly explain where these failed, and Scott understands HSM is far weaker evidence than he initially thought6, he still has a very strong intuitive feeling (based on years of dealing with probabilities) that this is some exceptional coincidence, and that prevents him from properly updating his posterior.

At the end of the day, this cannot be settled without going through our semi-formal derivation, understanding it, and either identifying the problem with it or accepting it (and thereby accepting lab-leak to be more likely).

Here is a quick summary of the mistakes made by those claiming HSM is strong evidence:

The first mistake is conflating Bayes factors with conditional probabilities. 1/10000 is the supposed conditional probability p(HSM Lab Leak), That should be divided by the conditional probability of HSM under Zoonosis. Markets were not identified as a high-risk location prior to this outbreak (This will be elaborated in the full response), and in SARS1 the spillovers were mostly at restaurants and other food handlers that deal more closely with wildlife. While it’s cool to point to the raccoon dog photo, that was a result of a retrospective search (we don’t know what other photos they took which in retrospect would be brought up as premonition). Unbiased data shows markets are not a likely spillover location for zoonosis. We originally estimated p(HSM Zoonosis)<0.1. Following more research we did to answer Scott’s questions, this is more likely <0.03. Even if it’s unclear how strong HSM is as an amplifier, it is clearly not some random location, with its high traffic (that alone should be at least 10x), many permanent residents, and the recurrence of early clusters in other seafood markets. It’s highly overconfident to claim it is less than a 1% location - It means Wuhan is somehow unique in that its largest seafood market is different from others and won’t form an early cluster. So the conditional probabilities under both hypotheses are fairly similar

- The obvious lack of evidence for a wildlife spillover in HSM further reduces this factor, making HSM negligible evidence.

Saar remains as committed to Rootclaim as ever. He’s even still committed to $100,000 bets on Rootclaim findings, settled via debate. He’d even be willing to re-debate Peter on lab leak! (Peter declined)

He does want to make some changes to the debate format - specifically, switching from video to text, and checking in more often with the judges to get feedback on their thought processes.

The switch from video to text seems reasonable. Saar was clearly flummoxed by Peter’s memory and agility, and wants a format where ability to remember/think on your feet is less important, and where you can do lots of research before having to think up a response.

The part with the feedback seems to be Saar wanting even more of an opportunity to identify disagreements with the judges early, and get a chance to tell them beforehand about issues like the ones above.

I’m sympathetic to both these changes, but I don’t think they would have changed the outcome of this debate.

The Aftermath: Rootclaim

Rootclaim is an admirable idea. Somebody called it “heroic Bayesian analysis”, and I like the moniker. Regular human reasoning doesn’t seem to be doing a great job puncturing false beliefs these days, and lots of people have converged on something something Bayes as a solution. But the something something remains elusive. While everyone else tries “pop Bayesianism” and “Bayes-inspired toolboxes”, Rootclaim asks: what if you just directly apply Bayes to the world’s hardest problems? There’s something pure about that, in a way nobody else is trying.

Unfortunately, the reason nobody else is trying this is because it doesn’t work. There’s too much evidence, and it’s too hard to figure out how to quantify it.

Peter, Saar, and the two judges all did their own Bayesian analysis. I followed along at home7 and tried the same. Daniel Filan, who also watched the debate, did one too. Here’s a comparison of all of our results:

Again, most people didn’t use these exact categories, I’m putting them in this format to make them easy to compare, and any errors are mine….

Again, most people didn’t use these exact categories, I’m putting them in this format to make them easy to compare, and any errors are mine….

The six estimates span twenty-three orders of magnitude. Even if we remove Peter (who’s kind of trolling), the remaining estimates span a range of ~7 OOMs. And even if we remove Saar (limiting the analysis to neutral non-participants), we’re still left with a factor-of-50 difference.

50x sounds good compared to 23 OOMs. But it only sounds good because everyone except Saar leaned heavily towards zoonosis. If raters were closer to even, it would become problematic: even a factor of 50x is enough to change 80-20 lab leak to 80-20 natural.

Saar’s perspective is that true theories should have many orders of magnitude more evidence than false theories (most of the Rootclaim analyses end up with normal-sounding percentages like “94% sure”, but that’s after they correct for potential model error). If that’s true, a 50x fudge factor shouldn’t be fatal.

But 23 orders of magnitude is fatal any way you slice it. The best one can say is that maybe this is no worse than normal reasoning. Among normal people who don’t use Rootclaim, many are sure lab leak is true, and many others are sure it’s false. If we interpret “sure” as 99%, then even normal people without Rootclaim are a factor of 10,000x away from each other. If we interpret “sure” as including more nines than that, maybe normal people are 23 OOMs away from each other, who knows? In this model, Rootclaim is no worse than anything else; it’s just legible enough that we notice these discrepancies. We’ve gotten inured to people failing to agree on difficult issues. Maybe Rootclaim gets credit for showing us exactly where we fail, and putting numbers on the failure.

Still, this is faint praise for a method that hoped to be able to resolve these kinds of disagreements. In the end, I think Saar has two options:

-

Abandon the Rootclaim methodology, and go back to normal boring impure reasoning like the rest of us, where you vaguely gesture at Bayesian math but certainly don’t try anything as extreme as actually using it.

-

Claim that he, Saar, through his years of experience testing Rootclaim, has some kind of special metis at using it, and everyone else is screwing up.

Saar gestured at (2) in the debate, repeatedly emphasizing that Rootclaim was difficult and subtle. But he mostly talked about things like the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy, which all participants already knew about and were trying to avoid. Maybe he should go further.

This wouldn’t necessarily be special pleading. When psychoanalysts claim their therapies work, they don’t mean that someone who just read a two page “What Is Psychoanalysis?” pamphlet can do good therapy. They mean that someone who spent ten years training under someone who spent ten years training and so on in a lineage back to Freud can do good therapy. When scientists say the scientific method works, they don’t mean that any crackpot who reads an Intro To Science textbook can figure out the mysteries of the universe. They mean someone who’s trained under other scientists and absorbed their way of thinking can do it.

If Saar wants to convince people, I think he should abandon his debates - which wouldn’t help even if he won, and certainly don’t help when he loses - and train five people who aren’t him in how to do Rootclaim, up to standards where he admits they’re as good at it as he is. Then he should prove that those five people can reliably get the same answers to difficult questions, even when they’re not allowed to compare notes beforehand. That would be compelling evidence!8

The Aftermath: Pseudoscience

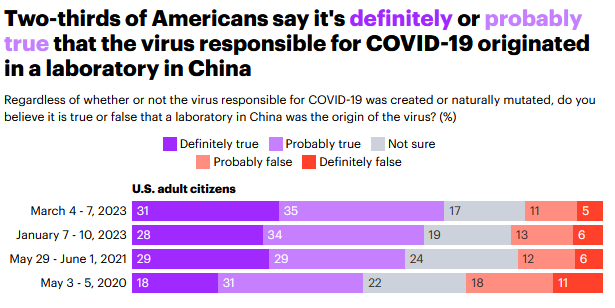

Suppose we accept the judges’ decision that COVID arose via zoonosis. Does that mean lab leak was a “conspiracy theory” and we should be embarrassed to have ever believed it?

The term “conspiracy theory” is awkward here because there were definitely at least two conspiracies - one by China to hide the evidence, one by western virologists to convince everyone that lab leak was stupid and they shouldn’t think about it. Saar cited some leaked internal conversations among expert virologists. Back in the earliest stage of the pandemic, they said to each other that it seemed like COVID could have come from a lab leak - their specific odds were 50-50 - but that they should try to obfuscate this to prevent people from turning against them and their labs. So the best we can say here is that maybe the conspiracies got lucky on their 50-50 bet, and the thing they were trying to cover up wasn’t even true.

Still, it’s awkward to use “conspiracy theory” as an insult when the conspiracies were real. Maybe a better question is whether lab leak is “pseudoscience”.

The argument against: lots of smart people and experts believed it was a lab leak. There were all those virologists giving 50-50 odds in their internal conversations. Even Peter says he started out leaning lab leak, back in 2021 when everyone was talking about it.

The argument in favor: since 2021, experts (and Peter) have shifted pretty far in favor of zoonosis. They’ve been convinced by new work - the identification of early cases, the wet market surveys, the genetic analysis.

What category of noun does the adjective“pseudoscientific” describe? It doesn’t necessarily describe theories : Newtonian mechanics wasn’t pseudoscience when Newton discovered it, but if someone argued for it today (against relativity), that would be pseudoscientific. It doesn’t even describe arguments : “we don’t have enough data to confirm global warming” was a strong argument against global warming before there were good data, and a pseudoscientific one now. Might we place the locus of pseudoscientificness in people, communities, and norms of discussion?

Peter’s position is that, although the lab leak theory is inherently plausible and didn’t start as pseudoscience, it gradually accreted a community around it with bad epistemic norms. Once lab leak became A Thing - after people became obsessed with getting one over on the experts - they developed dozens of further arguments which ranged from flawed to completely false. Peter spent most of the debate debunking these - Mr. Chen’s supposed 12/8 COVID case, Connor Reed’s supposed 11/25 COVID case, the rumors of WIV researchers falling sick, the 90 early cases supposedly “hidden” in a random paper, etc, etc, etc. Peter compares this to QAnon, where an early “seed” idea created an entire community of people riffing off of it to create more and more bad facts and arguments until they had constructed an entire alternative epistemic edifice.

If we don’t accept the judges’ verdict, and think lab leak is true, are we worried the zoonosis side has some misbehavior of its own? Yuri and Saar didn’t talk about that as much. High-status people misbehave in different ways from low-status people; I think the zoonosis side has plenty of things to feel bad about (eg the conspiracies), but pseudoscience probably isn’t the right descriptor.

The Aftermath: Ebb And Flow

During the debate, Peter accused the lab leak side of being constantly left flat-footed by new evidence. Sure, it had seemed plausible back in 2020, but they’d had to scramble to explain a steady stream of pro-zoonosis papers.

Afterwards, Saar and Yuri got some new evidence of their own. A Chinese team appeared to have found a T/T intermediate strain of COVID in Shanghai, possibly imported from very early in Wuhan. If true, it would provide new evidence against a double spillover, instead supporting Lineage A mutating into B in humans.

(You can see Peter’s response here - basically that we’re not sure it’s a true intermediate and not a reversion - if it were true, how come the two strains on either side of it got millions of cases, and it just got one guy in Shanghai? But if it were true, it would still be compatible with zoonosis - Lineage A would have spread from an animal and quickly mutated into B, the first A case would have been someone who left the wet market for a nearby area, and the first B case would have been someone who stayed in the wet market.)