Prediction Market FAQ

This is a FAQ about prediction markets. I am a big proponent of them but have tried my hardest to keep it fair. For more information and other perspectives, seeWikipedia, the scholarly literature (eg here), and Zvi.

1. What are prediction markets?

2. Why believe prediction markets are accurate?

3. Why believe prediction markets are canonical?

4. What are the most common objections to prediction markets?

5. What are some clever uses for prediction markets?

6. What’s the current status of prediction markets?

7. What can I do to help promote prediction markets?

1. What are prediction markets?

Prediction markets are like stock markets, but for beliefs about future events. For example, you can buy or sell shares in events like “The Democrats will win the next election” or “A Category 5 hurricane will hit Florida this year”.

Typically, a share pays out $1 if the event occurs, and nothing if it doesn’t. In this scenario, the price of the share will naturally represent the market’s belief about the likelihood of the event. For example, if a share in “The Democrats will win the next election” trades for $0.20, then the market believes there’s a 20% chance the Democrats will win the next election.

Why does this work? If it didn’t, you could make easy money. Suppose that a share in “The sun will rise tomorrow” was priced at $0.20, even though there’s a 100% chance that will happen. You could spend all your money on shares, and then, when the sun inevitably rose and the shares paid out $1, you would quintuple your money. If you think about different situations, you’ll realize that the only time you neither want to buy nor sell is when you think the share’s price correctly represents the probability.

Prediction markets have two good qualities: in ideal situations, they are accurate and canonical.

By accurate, I mean that that over the long run, they will be at least as accurate as any other source of information.

By canonical, I mean that they short-circuit discussion of “which expert should we trust?” or “how do we know which sources are biased?” All prediction markets speak with a single unified voice, that voice will always be at least as trustworthy as any individual expert, and it cannot be biased. If you’re not sure which of many competing experts (or supposed experts) to trust, you should always trust a prediction market instead of any of them. And the same is true of people on the opposite side of the political spectrum who doubt all the sources you trust and vice versa.

According to Pew Research , a poll of experts named “the breakdown of trusted information sources” as one of the leading challenges of the 21st century (who are these “experts”? was the poll fair? did Pew really say this, or am I making it up?) Millions of words have been written on how to solve this crisis, with most ideas being impossibly naive or dangerously authoritarian. I think prediction markets are a genuine solution, one that can’t come fast enough.

The rest of this FAQ tries to expand on these ideas, justify these surprising claims, answer some common objections, and explain where the prediction market industry is right now. It will start by presenting the theoretical argument for why prediction markets should work, then go into some reasons why they might work less well in real life, then try to bound how much damage the real-life problems can cause.

Because prediction markets work a lot like other markets (eg the stock market), some of this FAQ will be too basic and obvious for people who already have a good understanding of finance. You can skip these parts once you notice them.

2. Why believe prediction markets are accurate?

You can prove that one of two things must be true. Either over a long time scale, a prediction market will always be at least as good as the best expert, authoritative organization, or other information source. Or you can get rich quick. Here’s how:

Suppose that over a long time scale, a prediction market was consistently worse than the best expert (let’s sayNate Silver). Then you could make money by always betting on Nate Silver’s opinion. That is, if Nate Silver said there was a 90% chance the Democrats would win, but the market said only a 30% chance, you could buy shares in “the Democrats will win” and, on average, triple your money. You won’t always win, since Nate isn’t always right, but (by our supposition) on average you would make money on each bet. Repeat until you are rich, or the mispricing has been corrected.

Moving from the second person to the third person: if prediction markets were consistently worse than Nate Silver, then after a while someone would notice. This person could make a lot of money by betting on the market based on this observation. Once they did, the market would no longer be worse than Nate Silver.

2.1: What do you mean by “once they did, the market would no longer be worse than Nate Silver”?

To bet on a prediction market is to correct a mispricing.

Prices are set by the law of supply and demand. The more demand there is for something, the higher the price.

This is true in prediction markets too. The more demand there is for shares of “The Democrats will win”, the more a share will cost.

Suppose you see that Nate Silver says there’s a 90% chance the Democrats will win, but right now only costs 30 cents on the prediction market. Since these shares will probably triple in price, you decide to buy lots of them. Each time you try to buy one, it increases demand, and the price goes up.

How much will the price go up? Well, suppose you bought ten shares, and it only went up to 45 cents. You could still double your money by buying these, so you would probably buy more. Suppose it went up to 60 cents. You could still multiply your money by 1.5x by buying these, so you would probably buy more. In fact, the only case in which you wouldn’t want to buy more is when they’re worth exactly 90 cents. So if Nate Silver is better than the market, and Nate Silver says 90% chance for the Democrats, you’ll keep buying shares until they’re worth 90 cents each, then stop.

So once someone notices that a prediction market has made a mistake, they’ll be incentivized to make bets in a way that corrects the mistake. This means that we should expect prediction markets not to make easily-noticed mistakes. Since being worse than some other expert that everyone knows about (like Nate Silver) is an easily-noticed mistake, we should expect it to quickly be corrected.

2.2: Are you equivocating between “a prediction market will never make this mistake” and “there will be a financial incentive for someone to correct this mistake if a prediction market makes it?”

These are kind of the same thing.

There’s a rule in finance “there aren’t $100 bills lying on the ground”. Although some people might drop $100 bills on the ground, other people pick them up quickly, so you shouldn’t ever see a $100 bill lying on the ground.

But isn’t it possible that you’re the first person to notice?

In the real stock market, to a first approximation the answer is no. The first person to notice will be some trader at Goldman Sachs who has a complicated proprietary algorithm that watches 24/7 for the moment a $100 bill falls on the ground, then snaps it up within a millisecond of finding it. Unless you’re also an expert who spends all your time looking for mispricings, that guy will probably find them before you.

In general, the larger the mispricing, the more incentive there will be for people to look for it, and the more likely it is that some very experienced career trader who watches the market like a hawk will find it before you do.

I watch for a lot of different mispricings on a lot of different prediction markets, and I almost never find any that can make me more than a few hundred dollars, and even these are almost always in special cases where someone has crippled the prediction market for some reason (usually regulatory). After that, the incentive for some person to devote a substantial fraction of their time to pouncing on mispricings the moment they appear is too strong.

Sometimes in this FAQ I jokingly phrase that as “either prediction markets will be accurate, or you can get rich quick”. Unfortunately, it’s almost always the former.

2.3: You said this is true in ideal cases. What are the real-life cases where prediction markets might not be as accurate as other sources?

As the amount of money you can make from correcting a market goes to infinity, the accuracy (relative to other sources) approaches perfect. But if you can’t make much money on a market, it won’t necessarily be very accurate.

I know of a market called Futuur. It’s in English, but US citizens are banned from using it for regulatory reasons. They only accept cryptocurrency, which is hard to use and tends to implode. And they don’t have very good advertising, so not too many people ever hear about it. You can find all sorts of weird mispricings on Futuur - for example, they’re only 75% sure humans won’t reach Mars by 2024, whereas I’m about 100% sure of this. Can I make money by correcting this? There’s only about $100 in the market. So I would have to figure out a way to evade the ban on Americans, figure out how to use their cryptocurrency, tie up $100 in capital for a whole year - and then I would make about $33. Unless Futuur went bust, cryptocurrency imploded, or something else went wrong. Even though I know that in some sense I could make “free money” by correcting this market, I don’t feel like doing that (and apparently neither does anyone else). So the market remains mispriced.

There’s another market called PredictIt. In 2016 a lot of people bet Hillary, lost big, and left in disgust, so now the site has a small but consistent conservative bias. This is a mispricing it should be possible to make money by correcting. But because of a deal with US gambling regulators, PredictIt won’t let anyone bet more than $850 on their site. Every election year I go to PredictIt, make some bets, and dutifully collect a few hundred dollars in free money. But it would take more like $85,000 to fully correct the mispricing. And although I would be delighted to make tens of thousands of dollars in free money each election year, I can’t do that because of the gambling regulations. And although the contributions of a hundred people like me would add up to $85,000 and correct the mispricing, I guess there aren’t a hundred people who know about this strategy and care enough about making a few hundred dollars to pursue it. So the site continues to lean slightly conservative.

Here are some other reasons real prediction markets might fall short of the ideal:

-

They have transaction costs - eg fees or taxes - that make it not worth correcting small mispricings

-

There are easier ways to make money than to correct their mispricings. For example, on average you can make 5% per year in the stock market. If there’s a prediction market question about an event that will happen a year from now, and it’s mispriced by 4%, then it’s not worth buying shares in the prediction because you could make more profits by putting your money in the stock market. This is especially problematic for questions about events many years in the future, for example “will there be AGI in 2050?”

-

People don’t trust the prediction market. If there is a 10% mispricing, but a 15% chance that the prediction market will go bust, steal your money, or wrongly resolve the question against you - then on average you lose 5% by correcting the mispricing!

This doesn’t mean it’s impossible to have a truly accurate prediction market. There are two markets right now - Polymarket and Kalshi - where you can easily make $10,000+ by correcting mispricings. Unsurprisingly, I can’t find any big obvious mispricings on these markets!

2.4: Is there any empirical evidence comparing real prediction markets to experts?

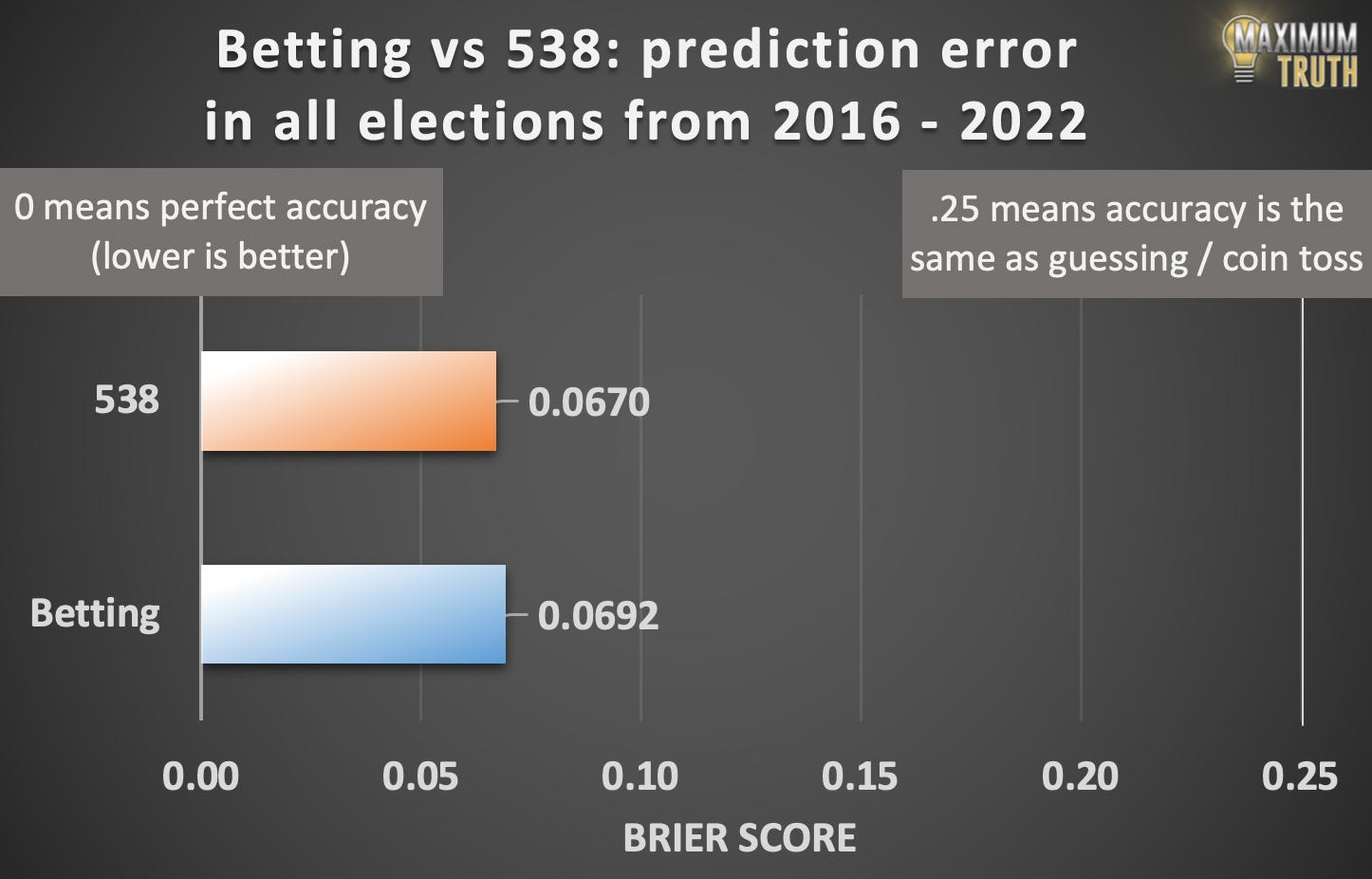

Yes. As predicted, prediction markets are about as accurate as Nate Silver. See Maxim Lott’s analysis here.

More generally, studies usually find that prediction markets beat the average person, various experts, and various other methods like election polling. They are somewhere between equal-to and slightly-worse-than complicated aggregation algorithms, but these complicated aggregation algorithms are rarely used in real life, and I consider them to be “prediction markets lite”, ie part of the same toolbox of forecasting technologies.

Hanson (2007) says (I have not individually checked each claim):

Remarkably, in every known head-to-head field comparison between speculative markets and other forward-looking institutions, the speculative markets have been at least as accurate. More often than not, they prevail. Orange juice futures improve on National Weather Service forecasts (Roll 1984), horse race markets beat horse race experts (Figlewski 1979), Oscar markets beat columnist forecasts (Pennock, Giles, and Nielsen 2001), gas demand markets beat gas demand experts (Spencer 2004), stock markets beat the official NASA panel at identifying the company responsible for the Challenger accident (Maloney and Mulherin 2003), election markets beat national opinion polls (Berg, Nelson, and Rietz 2003), and corporate sales markets beat official corporate forecasts (Chen and Plott 2002).

2.4.1: If prediction markets are only as good as Nate Silver or other experts, who cares? Why don’t we just skip the prediction markets and listen to the experts directly?

See the next section, “Why believe prediction markets are canonical?”

2.4.2: What if there are many equally impressive experts who disagree? What do prediction markets do then?

See the next section, “Why believe prediction markets are canonical?”

3. Why believe prediction markets are canonical?

By canonical, I mean that in ideal cases:

-

all prediction markets speak with a single voice

-

that voice cannot be manipulated by special interests and is free from bias.

-

you should trust a prediction market above your own opinion

-

when you’re not sure which of many competing experts to trust, you should trust a prediction market instead of any of them

Going through these claims one by one:

3.1: Why expect all prediction markets to agree with each other?

Either all prediction markets agree with each other, or you can get rich quick:

Suppose prediction markets disagreed. For example, suppose the RNC ran an Official Republican Prediction Market that said there was only a 10% chance Democrats would win the next election, and a 90% chance Republicans would. And suppose the DNC ran an Official Democrat Prediction Market that made the opposite prediction: 90% chance Democrats, 10% chance Republicans. Then you could buy a share of “Democrats will win” from the Republican market for 10 cents, plus a share of “Republicans will win” from the Democrat market for 10 cents, and be guaranteed to make $1 when one party or the other wins. You have turned 20 cents into a guaranteed $1. Repeat until you are rich or the mispricing has been corrected.

This is just what financial experts call “arbitrage”. You may notice that in finance, people always give specific prices for things like shares of stock, barrels of oil, or Bitcoins. People say things like “Google stock is up to $300”, but never “Google stock is up to $300 on the NYSE, but down to $200 on NASDAQ”. If that was true, people would buy it on NASDAQ, sell it on NYSE, make $100 in free money, and get rich quick.

In ideal situations, arbitrage forces everybody everywhere to agree on the same price for a financial instrument. Prediction markets turn claims about truth into financial instruments in a way which forces everybody everywhere to agree on how likely the claim is to be true.

3.2: Why expect prediction markets to be hard for special interests to manipulate?

Either a prediction market is not currently mispriced because of a manipulation attempt, or you can get rich quick. Argument:

Suppose a prediction market was currently mispriced because of a manipulation attempt. For example, suppose there is a prediction market for whether the sun will rise tomorrow. The true probability is obviously 100%, corresponding to a cost of $1.00. But suppose some special interest who wanted to trick people into believing the sun would not rise successfully spent money to bid the market down to only 10%.

This means that you can buy, for $0.10, a share which pays $1 if the sun rises tomorrow. In other words, you can dectuple your money for free. Repeat until you are rich or the mispricing has been corrected.

This may sound complicated in theory, but it plays out straightforwardly in real life. As a test, I tried to manipulate the market on whether Austin Chen, founder of Manifold Markets, would be charged with a felony. There’s no reason to think he should be, so the price started at 5%. I spent $200 in Manifold’s play money bidding it up to 95%. Within an hour, other investors noticed the mispricing and corrected it back down to 5% again.

3.3: Why expect prediction markets to be free from bias?

Either a prediction market is not currently mispriced because of bias, or you can get rich quick. The argument:

Suppose all smart people, including you, know that there is an 80% chance that the Democrats’ economic plan will create new jobs. But suppose that Republicans, because of their partisan biases, refuse to believe it, and say there is only a 40% chance. And suppose the Republicans set up their own prediction market where they bid the price of a share down to $0.40.

You can, of course, go on this prediction market, buy shares for $0.40, and double your money in expectation. Repeat until you are rich or the mispricing has been corrected.

I already described how something like this happens on PredictIt (a non-ideal prediction market that you can only make a few hundred dollars in expectation by correcting), and that I do in fact make a few hundred dollars every election season.

3.4: Why should I believe a prediction market’s consensus over my own opinion?

This is the same argument as “the prediction market will always be at least as accurate as the top expert” only with you in the place of the top expert.

Either prediction markets are at least as smart as you are, or you can get rich quick. The argument here is the same as “at least as smart as the smartest expert” argument in 2, except replacing “the smartest expert” with “you”. But just to lay it out explicitly:

Suppose you were smarter than some prediction market. Then if you disagreed with the market, usually you would be right and it would be wrong. So look for cases where you disagree with the market, buy those shares, and you will make money in expectation. Repeat until you are rich or the mispricing has been corrected.

I like this because it’s a good empirical test, and one that many people have tried. If you think you’re smarter than the prediction markets, bet on them and see what happens! I think most people will find that (over the long run) they lose money, and eventually this will cure them of their delusion that they can beat the markets.

A few people might find that (over the long run) they do win money, just as a few people (eg Warren Buffett) can consistently win money on the stock market. Hopefully those people will quit their day jobs and become full-time prediction market traders. They’ll become multimillionaires, and their hard work will ensure that prediction markets stay more accurate than the rest of us.

3.5: Why should I believe that a prediction market makes good decisions about which of many competing experts to trust?

Suppose you accept that a prediction market will always be at least as accurate as some well-known expert (eg Nate Silver). But what if you’re not sure who the real experts are? Or what if there are many experts, all saying different things, and nobody knows who to trust?

In this case, a prediction market will always be at least as good as any other source (including you) at telling good experts from bad, or at figuring out which of many good experts is the best. By this point you should be able to predict the argument, but for completeness’ sake:

Suppose you were better than the prediction market at determining which of many competing experts to trust, or how to aggregate the pronouncements of many experts into a single authoritative opinion. Then if you disagreed with the market, usually you would be right and it would be wrong. So look for cases where you disagree with the market, buy those shares, and you will make money in expectation. Repeat until you are rich or the mispricing has been corrected.

To ground this in a real example, suppose there is some new virus which might or might not spread to the United States. A Harvard professor of epidemiology says there’s a 70% chance it will spread, a Yale professor of epidemiology says there’s an 90% chance it will spread, and a guy in a tinfoil hat on Infowars says there’s a 0% chance it will spread because it’s all a fake government plot.

If I knew nothing else about this situation, I would probably think there’s about an 80% chance the virus will spread. I trust the Harvard and Yale professors equally much, and the tinfoil hat guy not at all.

Suppose I saw a prediction market that was only at 10%, because most people trusted the tinfoil hat guy. I would want to buy YES shares until the price got up to 80%, because in expectation I would octuple my money.

Suppose I saw a prediction market that was only at 70%. Now I wouldn’t be sure whether the prediction market was dumber than me (believed tinfoil hat guy) or smarter than me (they know a lot about epidemiology - or about the credibility of specific experts - and have decided to trust the Harvard professor over the Yale professor). Maybe I could improve on this. If I knew things about epidemiology, I could read over both professors’ arguments and try to figure out if one was better than the other. If I knew things about academia, I could pick over both professors’ resumes and see whether the Harvard professor seemed more distinguished or had more respect in her own field than the Yale professor. In the end, I might decide the prediction market was right to price it at 70% (in which case I wouldn’t do anything), or that actually both experts seemed equally expert (in which case I might bid it up to 80%), or that actually the Yale epidemiologist was better (in which case I might bid it up to 90%).

3.5.1: Isn’t it weird to give non-experts (like prediction market investors) the final judgment in which of two experts is right?

Yes, but I don’t think this is avoidable.

If there were no such thing as prediction markets, and the Harvard epidemiologist said 70%, and the Yale epidemiologist said 90%, and the tinfoil hat guy said 0%, and for some reason it mattered a lot to you which of these was true - then you would still have to make that decision.

If there’s some extremely authoritative source who can make the decision for you - let’s say the World Health Organization says “after reviewing all experts’ arguments, we believe that the final probability is 75%” - then great! Either:

-

The WHO is clearly the most trustworthy source - in which case we go back to the Nate Silver situation where the prediction market should be just as accurate as it is.

-

The WHO is just one more expert adding their opinion, in which case instead of the prediction market deciding between two experts, it can decide between three experts.

-

The WHO is completely untrustworthy. I worry some people will be offended by me even considering this possibility, but sometimes things like this are clearly true. For example, the EPA seems like it should be an authoritative-seeming source on the environment. But during the Trump administration it got captured by some pretty awful people and made some official-sounding statements about how the evidence showed global warming was fake. So we do need to be prepared for authoritative-sounding sources being completely untrustworthy. And if this happens, I hope prediction markets will figure this out and discount their opinion the same as they would the tinfoil hat guy. Or, if they don’t, at least you can get rich quick by betting against them.

3.6: Why does this matter?

I think prediction markets are our way out of the “crisis of trust” that threatens modern democracy. Lots of people doubt the experts, the government, and the media. Sometimes these doubts are justified; other times they’re loony. Most proposed solutions to this problem are authoritarian (eg ban all sources of information that the speaker doesn’t trust), and throw the baby (a free press capable of challenging authority when necessary) out with the bathwater (real disinformation).

Prediction markets solve this. When there are multiple competing experts (including fake experts) all saying different things, prediction markets offer a canonical source of truth that cuts through the noise. Either they will be at least as accurate as the experts you trust, or you can get rich quick. Since people on both sides know this, they’ll both trust prediction markets and end up converging to the same true beliefs.

…or they’ll lose all their money. I can’t guarantee that the misinformation-believers will all read and agree with this FAQ. Probably lots of them will think they’re right and the markets are wrong, and make bets on that basis. It’s your civic duty to take their money and get rich quick. Once this has happened enough times, they’ll stop believing that, calm down, and trust the markets again.

Another possibility is that they’ll come up with some reason why they have a philosophical objection to putting money on the prediction markets even though they claim to be sure the markets are mispriced. That’s fine. It at least provides a clear signal that lets the people who are operating in good faith find each other and identify the stragglers who aren’t.

There are lots of factual questions we would like near-impossible-to-bias social consensuses on! For example:

-

Will this coronavirus vaccine work / have too many side effects?

-

Will the climate change in such-and-such a way by such-and-such a year?

-

Would X amount of funding lead to a cure for cancer? Cheap renewable energy?

-

Will some politician’s pet project (high speed rail / an anti-poverty campaign / a plan to lower crime) succeed?

-

How long will a geopolitical conflict last? Who will win?

-

If we try this plan, then looking back on it ten years from now, will we agree it was a mistake?

Prediction markets give us a way to get accurate and canonical answers to questions like these, and to short circuit the usual discussions about how biased different information sources are. See below for some clever, more exotic ways we can use prediction markets.

4. What are the most common objections to prediction markets?

These are various objections, some wrongheaded, some true but nonfatal. There are many of them, making this section very long - you might want to skip over any objections you’re not worried about.

4.1: Would prediction markets be ruined by insider trading?

That is, suppose there is a market on whether President Biden will resign before the end of his term. President Biden has special knowledge of this, so he could bet on the true outcome and make a lot of money unfairly. He could even change his behavior (eg resign at an unexpected time) just to make more money. Isn’t this unfair?

One answer is that normal markets (eg the stock market) face these same problems, but manage them by making insider trading illegal. These laws don’t always work perfectly, but they work well enough that most people are happy to buy stocks.

Another answer is that, while this is bad for other investors, it’s not bad for the accuracy of prediction markets, or their use in creating unbiased social consensuses. In fact, knowing that President Biden is insider-trading on a “Will President Biden resign?” prediction market should only increase your confidence in it getting the right answer!

This is slightly too rosy, because if insider trading is bad enough for other investors, they might just not trade. This would be a partial effect: investors would be willing to overcome their fear for a big enough payday, meaning that concerns about insider trading probably would increase the likelihood of persistent small mispricings while still not allowing bigger ones (with the exact size depending on how frequent the insider trading was). It’s unclear whether this negative effect would be bigger or smaller than the positive effect from insiders having more information, so in different situations the market might end up either more or less accurate.

Overall, economists are split on whether insider trading makes markets more or less accurate. Commodities markets don’t really have insider trading laws right now, and seem to be about as accurate as anything else. I hope prediction markets will experiment with different insider trading rules, and the ones that best satisfy all participants and create the most accurate results will win out. If for some reason this doesn’t work, I don’t expect it to make too much difference either way.

4.2: Would prediction markets encourage harmful or illegal activities?

What about the risk of insider trading by committing harmful / illegal acts? That is, could President Biden’s doctor decide to poison him, then make money when he has to resign due to ill health?

I think the strongest evidence against is that this basically never happens in stock markets. Tesla stock would plummet if Elon Musk died or resigned, but nobody realistically worries that Musk’s doctor will short Tesla and poison him. Lots of corporations’ stocks would sink to zero if you burned down their offices and factories, but nobody shorts them and then commits arson.

Probably this is because there are laws against doing harmful and illegal things, and people have decided that stock market gains aren’t worth breaking the law and getting punished. Since prediction markets have only a tiny fraction of the amount of money that stock markets do, probably people won’t consider it worthwhile to commit harmful actions to manipulate them either. If you were going to murder someone to profit off a market, who would you rather kill: a US politician (the PredictIt market on the presidential election has a volume of about $600,000)? Or a Fortune 500 CEO (whose companies might have market caps in the hundreds of billions)?

4.2.1: What about prediction markets in very specific harmful or illegal activities?

I guess if you created a market in “Will someone burn down the 7-11 on Main Street tomorrow at 3:32 AM?”, then bet a lot of money, then did it, that would be bad.

I think realistically nobody would bet against you on that. But probably prediction markets should avoid hosting markets on these very specific bad things, just to make sure.

4.3: Would prediction markets give rich people more power?

That is, suppose we used prediction markets to assess socially important questions like “will the climate change by such-and-such a number of degrees by 2030?” It would be bad if rich people could manipulate our social consensus on this. But you move prediction markets by buying shares, and rich people can afford more shares than poor people. So doesn’t this mean that rich people can manipulate how concerned we are by global warming?

No. See 3.2 for the general reasons why it’s very difficult or impossible to successfully manipulate a prediction market. These reasons apply to rich people too.

Suppose a rich person spent $100 million to buy NO shares in “will the climate be warmer in 2030 than today?”, pushing the market’s implicit chance of global warming down to 1%.

That means if there is global warming, you could multiply your money by 100x by buying YES. I would immediately invest $10,000 in this market, so that I could get $1 million back in 2030 and retire rich.

My $10,000 isn’t going to be enough to fully move this market all the way back - we already said the rich person spent $100 million manipulating it. But “you can get a free $1 million quickly with no downside at an evil rich person’s expense by correcting an obvious misconception about global warming” sounds like the sort of thing that could make it to the front page of Reddit (to put it lightly). I think more than enough people would learn about this to fully correct the mispricing.

Is there any amount of money that could successfully manipulate a market? I think the answer is that you need to have more money than the sum total owned by everybody else in the world who wants to make $1 million quick. And at the limit, there’s always Goldman Sachs - who watch financial markets very closely, definitely want to make $1 million quick, and have a lot of money.

So I think the most honest answer to this objection is: if you are an evil rich person reading this FAQ, then it will definitely work for you. Please sink $100 million into reducing a prediction market’s chance of global warming to 1%. And make sure you tell me first, so that I can fully marvel at your evil genius. This will work great for you and nothing will possibly go wrong.

4.3.1: But wouldn’t the subtle biases of rich people (which they might genuinely believe) still affect the market more, since they have more money?

No. See 3.3 for the general reasons why we should expect prediction markets to be free from subtle biases which people genuinely believe. These reasons apply to rich people too.

Suppose rich people have subtle biases which make them wrong more often than poor people. And suppose rich people (wrongly) believe global warming is 75% likely, but poor people (correctly) believe it’s 99% likely.

This just reduces to the Nate Silver situation earlier, with poor people playing Nate Silver. The aggregated opinion of poor people is “an expert” which is right more often than the markets. It’s easy for someone to notice this and get rich quick (in expectation) by betting on what poor people think. Since lots of people can easily notice this and want to get rich quick, eventually they will correct the mispricing.

Even if rich people have so much more money than poor people that no group of poor people, however large, can ever correct a rich person mispricing, eventually some smart rich person will hit upon this strategy themselves. If no individual rich person does it, Goldman Sachs will definitely do it.

4.3.1.1: What if both rich people and poor people have biases, and neither one is consistently more right than the other? Won’t the market still reflect rich people’s biases rather than poor people’s?

Not if it’s possible for anybody to notice these biases and correct for them. Treating the aggregate opinion of poor people as an expert was just one example. If the winning strategy is something like “trust rich people on financial questions, poor people on environmental questions, and the point exactly halfway between them on social questions”, then whoever discovers that strategy can get rich quick. The more often people use prediction markets, the easier it should be to detect strategies like these.

4.4: Aren’t prediction markets worse than superforecasting?

“Superforecasting” refers to a variety of forecasting methods similar to those pioneered by Philip Tetlock and the Good Judgment Project. Typically, they would do something like:

-

Ask many smart people to give probabilistic answers to a very well-specified question

-

Have some incentive mechanism in place where people who give good answers gain reputation, and people who give bad answers lose reputation

-

Filter the answers through some complicated aggregation algorithm. Partly the algorithm will weigh the answers of people who have been right before (“superforecasters”) more heavily, but probably it will also do other things.

-

After the event happens, use the outcome to update everyone’s reputation and refine the algorithm.

Superforecasting uses some of the same ideas as prediction markets - probabilistic forecasts, incentives to get the right answer, aggregation methods that favor people with good track records. In studies comparing superforecasting tournaments to small prediction markets, the superforecasting tournaments have done equally well or even slightly better.

My goal with this FAQ is not to claim that prediction markets are always better than superforecasting. I think of both as part of the same revolution in forecasting technology, and would be happy with policy-makers or other important people using either. Still, I do think that each has situations where they might be a better fit than the other.

Superforecasting tournaments shine on questions so far in the future that financial incentives start to lose force (for example, people are unlikely to place bets on questions about 2100, when most of them will be dead anyway). They’re also good in situations where you can’t get a big prediction market together - superforecasting scales down more gracefully, since you can identify individuals as superforecasters and consult them even in situations where you can’t get a full tournament together.

Prediction markets shine in avoiding advanced manipulation attempts, in providing a single canonical answer when someone might worry that any given tournament was biased, and in aggregating the results of superforecaster tournaments with each other and with other sources.

Remember that a superforecasting tournament can be considered an “expert”, like Nate Silver. So by the argument in Part 2, we should expect that a big prediction market won’t consistently be worse than any given superforecasting tournament, as long as the tournament’s answers are public knowledge. If there were ever a superforecasting tournament that consistently outperformed prediction markets, that would be a simple mispricing, people would correct it, and the market would eventually agree with the tournament.

4.5: Aren’t prediction markets gambling? Isn’t gambling bad and addictive?

Yes, sort of. But most countries allow forms of gambling that aren’t too addictive and have some social value. For example, investing in stocks, or investing in commodities futures. I think prediction markets are more like this than like traditional gambling in casinos.

People who want to gamble can already buy cryptocurrencies, or trade stocks on Robin Hood, or (in 20 states) place online sports bets on sites like DraftKings. All these things seem more addictive than, and have less social utility than, prediction markets. I don’t think promoting or legalizing prediction markets is going to make the gambling situation much worse than it is already - so given how useful I think they are, I think they would be net positive.

People who are more concerned about the gambling aspect might want to stick to play money prediction markets, which wouldn’t have this problem.

4.6: Where does the money in prediction markets come from? That is, if “you get a dollar when the Democrats win”, who provides the dollar?

In the abstract, prediction markets pair up people who want to bet on different sides of a proposition. For example, if a market says that there’s a 75% chance that the Democrats win, then they pair up someone willing to buy a share in “The Democrats win” for $0.75 with someone willing to buy a share in “The Democrats lose” for $0.25, for a total of $1 spent on these two shares. Then, when the Democrats either win or lose, the person with the correct share gets the $1.

In practice it’s annoying to have to wait for someone to take the opposite side of the trade, so some people (or bots!) play “market maker” and are willing to take your bet on the assumption that someone else will come along soon to take the other side. But it’s usually safe to abstract this step away and just imagine people betting with each other, using the market as an intermediary.

4.6.1: Then why should anyone play prediction markets, when on average they’ll only break even? It seems like this is a worse deal than stocks, which tend to go up over time.

Every dollar someone wins on a prediction market corresponds to someone else’s loss; in expectation; across all participants, the average gain is 0. But the stock market tends to go up over time, as businesses expand to new areas and invent new products; across all participants, the average gain is about 4% per year. So why ever invest in prediction markets instead of stocks?

Whatever the theoretical answer to this question, lots of people do invest in prediction markets instead of stocks sometimes; several existing prediction markets have questions with hundreds of thousands of dollars in trading volume. You would have to ask those people why they do it. Maybe it’s because it’s fun. Or maybe it’s because they think (rightly or wrongly) that they’re above average and can make a profit. This is no different than other zero-sum games like sports betting, which attracts billions of dollars each year.

The futures and commodities markets are also zero-sum, but attract billions of dollars by giving companies an opportunity to hedge risk. For example, a nickel mine might get rich if the price of nickel goes up, but go bankrupt if the price of nickel goes down. And they might prefer a predictable world where they get a small but guaranteed profit no matter what happens to nickel prices. So they bet some amount of money on commodity markets that the price of nickel will go down, and then their income is the sum of what they make from their nickel mining and from their bets - which, if they handled their hedging correctly, should be a small but guaranteed profit. Prediction markets would allow hedging of other types of risk - for example, import-export businesses might want to hedge against the risk that a protectionist politician gets elected, or tourism companies might want to hedge against a pandemic that closes international borders. These people would inject enough money into the market to subsidize sophisticated speculators.

Finally, I envision that someday people who want to know the answer to specific questions can subsidize prediction markets on them. For example, the Democratic Party might subsidize a conditional market (see 5.1) about which Democratic primary candidate is most likely to win the general election. Their money would go to giving the average investor a 4% (or some other number) rate of return - although of course winners would gain more than that and losers would still lose on net. I think this is the most likely way for prediction markets to become very big.

4.6.1.1: If people use prediction markets to hedge risk, won’t that distort them?

That is, suppose that an import-export business spends millions of dollars betting that Trump will win in order to hedge against his protectionist policies. Since their bets aren’t based on the real chance of Trump winning, won’t that distort the market?

No. Suppose that everyone knows Trump has a 50-50 chance of winning. And suppose the import-export business, in the process of hedging risk, bids it up to 90-10. Since you know Trump has a 50-50 chance of winning, you can get rich quick by bidding it back down to 50-50. From your point of view, the import-export business is (in expectation) giving you free money. But they’re still happy to do it, because they’re hedging their risk successfully.

4.7: Aren’t a lot of the questions we care about inherently subjective or hard to measure?

This is a frequent problem for prediction markets. For example, we might want to know something like “will we get human-level AI before 2050?” But how do we define “human-level AI”? If there’s an AI that’s much better than humans at most tasks, but much worse at a few, is that “human-level”? If there’s an AI that seems human-level in demos, but the team that makes it won’t let it be independently tested, should that count? If it works through some kind of Frankenstein chip that combines vat-grown brain tissue with computing machinery, is that still an “AI”?

Prediction markets have found a few ways around this problem.

First, many groups (for example, Metaculus) try to define their resolution criteria very carefully. A typical Metaculus question on AI sounds like this:

We will thus define “an AI system” as a single unified software system that can satisfy the following criteria, all completable by at least some humans.

Able to reliably pass a 2-hour, adversarial Turing test during which the participants can send text, images, and audio files (as is done in ordinary text messaging applications) during the course of their conversation. An ‘adversarial’ Turing test is one in which the human judges are instructed to ask interesting and difficult questions, designed to advantage human participants, and to successfully unmask the computer as an impostor. A single demonstration of an AI passing such a Turing test, or one that is sufficiently similar, will be sufficient for this condition, so long as the test is well-designed to the estimation of Metaculus Admins.

Has general robotic capabilities, of the type able to autonomously, when equipped with appropriate actuators and when given human-readable instructions, satisfactorily assemble a (or the equivalent of a) circa-2021 Ferrari 312 T4 1:8 scale automobile model. A single demonstration of this ability, or a sufficiently similar demonstration, will be considered sufficient.

High competency at a diverse fields of expertise, as measured by achieving at least 75% accuracy in every task and 90% mean accuracy across all tasks in the Q&A dataset developed by Dan Hendrycks et al..

Able to get top-1 strict accuracy of at least 90.0% on interview-level problems found in the APPS benchmark introduced by Dan Hendrycks, Steven Basart et al. Top-1 accuracy is distinguished, as in the paper, from top-k accuracy in which k outputs from the model are generated, and the best output is selected.

By “unified” we mean that the system is integrated enough that it can, for example, explain its reasoning on a Q&A task, or verbally report its progress and identify objects during model assembly. (This is not really meant to be an additional capability of “introspection” so much as a provision that the system not simply be cobbled together as a set of sub-systems specialized to tasks like the above, but rather a single system applicable to many problems.)

Resolution will come from any of three forms, whichever comes first: (1) direct demonstration of such a system achieving ALL of the above criteria, (2) confident credible statement by its developers that an existing system is able to satisfy these criteria, or (3) judgement by a majority vote in a special committee composed of the question author and two AI experts chosen in good faith by him, for the sole purpose of resolving this question. Resolution date will be the first date at which the system (subsequently judged to satisfy the criteria) and its capabilities are publicly described in a talk, press release, paper, or other report available to the general public.

Even this isn’t perfect (which models are “the equivalent of” a 1:8 scale Ferrari 312?), but in practice once you get to this level of details people mostly stop worrying about this.

Another method (mostly associated with Manifold) is to just leave it up to human judgment - specifically, the judgment of the person who made the market. For example, I could make a market in “By 2050, will there be an AI which Scott Alexander thinks qualifies as ‘human-level’?” This will force market participants to price in the risk that I have bad judgment or act dishonestly. But perhaps these risks are small. For example, I might say elsewhere what I think qualifies as “human-level” AI, or you might think human-level AI will be so obvious when it comes that I will definitely agree with you about it. As for honesty, this could be enforced either legally or by reputation. Someone who has resolved their past 100 prediction markets honestly will probably resolve this one honestly too, especially if they get paid to do so and will never get customers again if they lie. When we invest on the normal stock market, we trust that our brokers / the NYSE / etc won’t run off with our money, and this trust is usually well-deserved. Even when we make an online purchase, we trust that the store we’re sending our money to won’t steal it and refuse to send us the product. It would be an exaggeration to say that trust is a solved problem, but evidence from Manifold suggests that most people price in a <1% chance that well-known market makers with good reputation resolve dishonestly.

If prediction markets got big enough, they could spawn trusted “resolution companies” who individual markets and market-makers could outsource their resolution to, for a fee. If these companies were ever dishonest, they would lose all their business from then on, so they would probably be as honest as other businesses like your broker / the NYSE / various online stores / etc.

4.7.1: Isn’t a lot of the “crisis of trust” around questions that might never have clear future answers?

For example, consider the debate around whether Donald Trump is a Russian agent. Maybe no proof will ever come out either way. Or maybe some evidence will appear that seems to prove one side or the other, but people will continue to deny it for political reasons, and the problem of resolving the prediction market will be just as hard as the problem of answering the original question.

Indeed, prediction markets aren’t very good at this, and are only fully trustworthy on questions where the true answer will eventually become apparent.

Still, they might not be completely useless. For example, if you’re worried about Trump being a Russian agent because you expect him to pursue pro-Russia policies, you can start markets in whether he pursues those policies. Or you can start a conditional market (see 5.1) on whether, if Russia ever releases its past intelligence data many years from now, the data confirm/disconfirm that Trump was an agent. See Part 5 for other clever ways you might try to address this problem.

4.8: “Meme stocks” like Gamestop and AMC sometimes remain mispriced indefinitely. How do we know this won’t happen with prediction markets?

Meme stocks are a type of Ponzi. It’s “reasonable” to buy Gamestop at some inflated price, because - who knows? - someone else might buy it at an even more inflated price tomorrow. And this can keep going arbitrarily long, or at least long enough for you to get out with a profit.

Unlike meme stocks, prediction markets have a clear resolution date. If you’re predicting who will win the next election, the market will go to 100% or 0% after the election finishes. No matter how many memes there were, you wouldn’t buy a share in “the Democrats will win the election” for 99% the day before Election Day if you knew they would definitely lose. But that means prediction markets should be accurately priced the day before Election Day, which means you shouldn’t buy at an inaccurate price two days before Election Day, and so on.

I can’t say for sure that no prediction market will ever get mispriced for meme reasons, but they should be much more robust against meme mispricings than the stock market. And even the stock market doesn’t have too many meme stocks.

4.9: How do prediction markets deal with outcomes in the far future?

Suppose there is a question “who will win the 2100 election?” Currently it says 25% Democrats, 75% Republicans, and I believe it should be 50-50 (we’ll ignore third parties, or the possibility of America not existing in 2100, for now). So if I bet on the market, I can (in expectation) double my money.

But there are many better ways to double your money by 2100. For example, if the stock market grows 4% per year, I should expect any money invested in the stock market to multiply by 20x in 2100. So just doubling it in a prediction market is a bad option.

Realistically, this means prediction markets won’t work well for far-future events. These might be a better match for forecaster tournaments or some other structure, where we get the forecaster track records through present events, then use those track records weighting their far-future predictions (see also 5.5). There are already good forecasting tournaments on some far future events.

But if you really wanted to use a prediction market, you could theoretically solve this by putting investors’ money in index funds while they waited. Then the winner would get their (and the losers’) original deposits and investment profits, and it would go back to being a better option than investing in index funds directly. In practice this seems complicated and I wouldn’t expect it to work.

4.9.1: What about predicting things that would make it impossible or pointless to win money, like human extinction?

Again, these questions probably aren’t great matches for prediction markets, and you should use forecasting tournaments or some other method (see also 5.5). If you really wanted, you might be able to make it work in theory through a mechanism sort of like this one.

5. What are some clever uses for prediction markets?

Here’s a non-exhaustive list:

5.1: Conditional prediction markets / decision markets

Suppose the government is trying to decide whether to throw its weight behind Vaccine A or Vaccine B for some deadly disease. There are some experts behind both, both sets of experts accuse the other of being in the pay of pharmaceutical companies, and decision-makers don’t know who to trust.

They might make two prediction markets, like:

-

If we decide to go with Vaccine A, will at least X people die from the disease?

-

If we decide to go with Vaccine B, will at least X people die from the disease?

If the first prediction market is 60% and the second one is 40%, they might decide to use Vaccine B. Then they can give refunds to everyone who bet on the first market (since it will never be tested) and resolve the second market normally.

Remember, decision-makers usually aren’t experts themselves, and have the same “which experts do I trust?” problem as the rest of us - except worse, because there are more special interests spending more money to confuse them. They could find markets like these very helpful.

One downside of decision markets is that you have to be very careful to choose the right outcome. For example, if people can both die from the disease or be disabled by the disease, this market will choose the vaccine that causes the fewest deaths, regardless of how much disability it causes. Because of issues like these, decision markets should only be used as one input in decision-making, not as the entire process.

Another downside is that sometimes conditionals can interact in non-intuitive ways that make conditional prediction markets inappropriate or slightly off. See this article for more details.

5.2: Politician pledge markets

Suppose that President Biden pledges to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030. In theory this is a noble goal. In practice, it’s cheap talk; he can institute whatever policies he wants, but he has no incentive to make them work. By 2030 he’ll be retired and maybe even dead.

Instead, he could pledge to move prediction markets about 2030 emissions. Suppose that before he made his pledge, prediction markets said there was only a 5% chance that emissions would halve by 2030. Biden might pledge that within a year, prediction markets would say there was a 80% chance of this. Then he could announce new policies. If they were good policies that would almost certainly halve emissions by 2030, the prediction markets would go up to some very high number. If they were bad policies, the prediction markets would stay low, and Biden would either have to propose better policies, or admit having failed at his pledge.

For more, see Instead Of Pledging To Change The World, Pledge To Change Prediction Markets.

5.3: Attention markets

Suppose you’re a very important person, like the President of the US, or the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. You want ordinary people to be able to raise important problems to your attention (for example, a threat to national security, or a major flaw in your product). But if you made your email address public, millions of people would send you dumb complaints or random screeds every day.

Prediction markets could solve this. Tell people who have a complaint to start a conditional prediction market in “If the President personally looks over this complaint, will he believe it was a good use of his time?” Then agree to look over any complaints that get above 50% (plus some randomly selected ones, to encourage people to keep the probability accurate even when it’s below 50%). When you’re done, tell people whether you thought it was a good use of your time, so the market can resolve. If the markets start sending too many complaints your way, your bar for “good use of my time” will go up, and the system will naturally self-correct.

I’ve sometimes used this system to resolve moderation issues around this blog, with generally good results.

5.4: Replication Markets

Suppose you have one hundred scientific studies that got kind of weird results and that you think might have made a mistake somewhere. But you don’t have enough money to repeat all one hundred studies; in fact, you only have enough money to repeat one.

You can open up a hundred prediction markets, like:

-

If we decide to redo Study #1, will we get the same results?

-

If we decide to redo Study #2, will we get the same results?

…and so on. Obviously the market can’t be sure how studies will turn out - otherwise we wouldn’t need scientists or experiments! But this acts as a force multiplier, letting you get predictions about 100 studies even if you can only do one - and might guide which one you redo.

Predicting replicability—Analysis of survey and prediction market data from large-scale forecasting projects, published in PLoS One , attempted this and found the markets were pretty accurate - 73% was their headline finding, but read the study for more. One participant wrote about his experience: How I Made $10K Predicting Which Studies Will Replicate. You can learn more about this project at replicationmarkets.com

Eliezer Yudkowsky once wrote a story about a civilization that settled legal questions this way. They had a few truly brilliant legal experts - the equivalent of US Supreme Court Justices - but not enough to answer every possible question that might come up. So for each question they made a prediction market:

-

If we submit Question #1 to the Supreme Court, will they rule in favor?

-

If we submit Question #2 to the Supreme Court, will they rule in favor?

…and so on. A few randomly selected questions went before the Supreme Court each year, and the corresponding markets were resolved normally. In every other case, the market’s verdict was final, and bettors got their money refunded.

5.5: Asking people who are good at prediction markets to do other things

Prediction markets have many limitations. They can’t predict far future events. They have trouble predicting things that involve money becoming worthless (eg human extinction). There are complicated biases in predicting conditionals.

One way around these is to see who keeps winning prediction markets, assume those people are smart and good at predicting things, and ask them to predict these issues directly.

This would lose the well-aligned-incentives and canonicity of prediction markets. But it might be better than asking random experts in related fields who have never shown any particular skill at prediction to do this. Or the prediction market experts could work with the domain-relevant experts to come up with a joint statement.

Samotsvety is a group of some of the world’s top forecasters. They have released predictions on various risks and issues that markets/tournaments aren’t a good match for, using the same methodology that they use when predicting in markets and tournaments. I trust them less than I would trust a well-functioning market or tournament, but still quite a substantial amount.

5.6: Education

Even if nobody uses them for anything important, prediction markets’ existence has a salutary effect on the discourse.

There’s something about framing a question as “at what odds would you bet on this in a prediction market?” that seems to make people smarter. Some lifelong Democrat will be going on about how the Democrats can’t possibly lose the next election and then you ask “at what odds would you bet on this in a prediction market?” and they suddenly backtrack.

Even the idea that we can think of events as occurring at some specific probability seems nonintuitive to a lot of people, and encountering prediction markets is the best way I know of to make those people understand this.

Prediction markets also do really well at communicating a sense of how you’re not always right. A lot of people list off all the things they and their political side have been right about, cleverly eliding or making exceptions for every time they were wrong. Thinking more in terms of “How much money would you have been able to make on a prediction market using your skill of magically always being right?” seems to sometimes snap these people out of it, and help them avoid overconfidence.

I would love if everyone on all sides of a debate had some prediction market experience, even if we weren’t able to use prediction markets to settle the debate directly.

6. What’s the current status of prediction markets?

The United States currently classifies prediction markets as gambling, so real-money prediction markets are mostly illegal. This has forced markets to pursue one of three strategies:

-

Operate outside the United States, closed to US citizens. Polymarket fills this niche effectively.

-

Make special deals with US regulators for exemptions to the usual restrictions. Usually these deals involve promises to have a very limited set of questions or deal in very small bets only. PredictIt used to be the leader here, but regulators changed their mind and are shutting it down. Kalshi will probably replace it.

-

Operate using play-money only. Here Manifold is the leader. You could also think of superforecasting tournaments like Metaculus as a version of this.

I claim that the main reason prediction markets haven’t fulfilled their potential and become a major pillar of worldwide decision-making is that none of these solutions are really adequate.

For whatever reason, most people interested in prediction markets are American, so Polymarket has a limited userbase.

The regulators are pretty harsh, so the companies that strike deals to get exemptions usually have to trade away most of their functionality. Kalshi can only ask a few specific regulator-approved questions; the limits are so harsh that they’re not even allowed to predict elections.

Play-money prediction markets like Manifold are a lot of fun, but there’s a limit to how much work people will do to earn play money. I want a world where the people who are best at correcting mispricings in prediction markets can make full-time jobs out of it, and where there are prediction market equivalents of Goldman Sachs where hundreds of brilliant people work together with cut-throat efficiency to find mispricings the moment they appear. Play money won’t get us there.

Real money prediction markets tend to have between four- and six-digit (very occasionally seven-digit) volumes on most questions. Play money prediction markets have between one- and four-digit numbers of traders on most questions.

Most big prediction markets are usually within 10% of each other and the best outside experts, but not always within 1%. Traditional financial markets are usually within 1% of each other, so I think this is because the prediction markets are still too small to have sub-1% accuracy. I hope that as they grow bigger they can reach this milestone.

7. What can I do to help promote prediction markets?

If you’re an ordinary person with no special expertise or skills, I think the best thing you can do is create a Manifold Markets account, bet on topics that are interesting to you, and create markets for any interesting topics that don’t have one yet. I think this could be helpful for a few reasons:

-

It’s hard to really understand prediction markets until you’ve played a few yourself.

-

Realistically most people who read this FAQ will forget about it within a few weeks, but Manifold is genuinely fun and maybe a little addictive, and being part of a prediction markets community like that will keep the topic in your mind.

-

The more people play on Manifold, the better Manifold-the-company does, the more new features it can add, and the more likely it is to be able to reach more people and turn them into true believers.

-

Random people with their own idiosyncratic interests and community connections are valuable for Manifold. One of their first big breaks was attracting a bunch of random fans of the YouTube streamer “Destiny”. They would bet on what new episodes he would produce and whether he would win his debates. The more random communities like this get sucked in, the better.

-

If you have no special expertise or skills, I expect you would mostly lose money on prediction markets, and I would rather this be play money than real money.

7.1: …if I’m an expert in some unrelated field, like biology or physics

You can still try playing on Manifold, but I would also recommend you get an account on Metaculus and try out questions in your area of expertise. Metaculus aims to be policy-relevant, and the more experts it has forecasting scientific questions, the more likely it is to get them right.

You should also feel free to try Metaculus even if you’re not an expert - their algorithm will see how often you’re right, and upweight or downweight your guesses accordingly.

7.2: …if I’m a hotshot financial trader?

Consider betting on real money prediction markets.

If you’re outside the US, your best bet is probably Polymarket (some Americans have found ways to use VPNs and crypto to trade on Polymarket despite the ban on US citizens; I don’t know how safe or recommended this is).

If you’re inside the US, your best bet is probably Kalshi.

I think the sort of person who can make money day trading stocks or crypto can also make some money playing prediction markets, probably with more social utility. As with any investment, please be sure you’re actually a hotshot financial trader, and don’t bet more than you can afford to lose.

7.3: …if I’m a blogger or journalist?

You should consider including or citing prediction markets in your articles.

Instead of saying “two polls say that the Democrats have a slight lead in the election, versus one poll that says the Republicans have a big lead”, you can say “Prediction markets say the Democrats have a 64% chance of winning the election”.

Instead of saying “given their new logistical problems, experts are increasingly skeptical that Ukraine can retake Donetsk by winter,” you could say “Prediction markets say there is only a 12% chance Ukraine will take Donetsk by winter, which is down by 9% since the logistical problems started”.

I recently had to read many articles on Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, which all repeated that “rumors said” Twitter was about to go down because of his mass firing. Meanwhile, there were several prediction markets on whether this would happen, and they were all around 40%. If some journalist had thought to check the prediction markets and cite them in their article, they could have not only provided more value (a clear percent chance instead of just “there are some rumors saying this”), but also been right when everyone else was wrong.

Here are some examples of journalists talking about prediction markets:

-

Bloomberg: Election Prediction Markets Show Kenosha Is Helping Trump

-

The Capitolist: As Presidential Speculation Swirls, DeSantis Holds Lead Over Trump In 2024 Prediction Market

-

Fortune: Will We Have A COVID Vaccine By Year End? Here’s What The Prediction Markets Say.

But you don’t have to make the prediction market the focus of your article. If you’re writing about a promising new cancer cure, you might spend a paragraph mentioning that prediction markets think there’s only a 15% chance it will get approved by the FDA. Or if you’re writing about a trial, you could cite the prediction markets’ probability of a guilty verdict.

7.4: …if I’m a leader or policy-maker in some organization?

Although prediction markets can be helpful in gathering policy-relevant information and making decisions, I would be nervous about someone using them for something important before they fully understood what they can and can’t do.

If you’re very interested in this, it might be worth contacting Metaculus or Good Judgment Project about a partnership where they walk you through ways to use superforecasting for your organization. I don’t know of an easy way to get exactly this same service with a real prediction market yet.

Some companies have their own internal prediction markets, most famously Google. Last I checked, Google was offering their services to other companies that wanted to try the same thing, so you might want to try getting in touch with them.

7.5: …if I’m an entrepreneur who wants to get involved in this space?

I’ll be honest. Most of the proposals I see for new prediction market-related companies are bad. Existing prediction-market-related companies are pretty good, and I’m not sure how you would improve on them in the current environment. The main barrier everyone is facing is regulatory, and I don’t know how adding one more entrepreneur would fix this.

On an earlier version of this FAQ, a commenter disagreed, saying:

Some projects that I think could be very high EV to further popularize the use of prediction markets and advance the state of the art:

- You know how Splitwise facilitates splitting an arbitrary bill with your friends? Something like that, but to facilitate making a simple prediction market in a small group, and leaving it to you guys to “pay out” in money or whatever. Manifold is not very technologically suitable for this and it probably won’t be soon.

- It would be amazing to have the union of Polymarket and Manifold – a cryptocurrency-based tool for anyone to create markets, resolve markets, browse available markets, and participate in markets. There was a wave of tools that tried to do this five years ago, like Augur and Gnosis, but to my understanding, they basically failed due to Ethereum gas prices making them intractable to use at scale. If someone magically built this on e.g. some kind of Ethereum L2 with manageable fees, it could be The Real Deal for prediction markets that everyone (at least cryptocurrency-literate people) can participate in and which governments can’t really shut down. Polymarket isn’t this, because Polymarket doesn’t let people create and resolve their own markets; it relies on the Polymarket central authority, which can be censored, has limited throughput, and has limited trust. If this tool existed and had a proliferation of markets with 5 or 6 figures of liquidity, imagine how different conversations in rationalist-adjacent spaces about COVID, or AI forecasting, or public policy, would look.

- Any kind of experimentation that attacks the problems we are observing in practice with prediction markets, like working out how to make good multiple choice and numeric distribution market mechanisms, incentivizing accurate prices on long-term markets, and figuring out how to make markets user-friendly for people. We don’t know how to do these things at Manifold and we are just a couple of people guessing and trying stuff out. More people advancing the state of the art on any of these subproblems would be extremely beneficial. Maybe the answer is that Robin Hanson and some other guys definitely worked it out in some papers somewhere, in which case, please come tell us about it.

tl;dr If you believe that working public prediction markets could make a big difference to the world, you should consider trying to produce them.

If you have an idea for a prediction-market-related company, feel free to run it by me. You can reach me at scott@slatestarcodex.com.

7.6: …if I’m the head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission?

Please legalize real-money prediction markets in the United States. If it helps, here are a bunch of really famous economists including a Nobel laureate explaining why you should do this.