Prospectus On Próspera

Who among us hasn’t looked out at the great edifice of human civilization in all its complexity, and thought “Yeah okay but I could do it better”? Centuries of utopian communes, micronations, and seasteads have dreamed of rebuilding society from first principles, free from entrenched interests and the debris of the past. If you got all the laws and values just right, maybe you could prevent poverty and corruption from finding their first footholds. Do the “liberty and justice for all” thing, but for real.

And who among us, having had the dream, hasn’t entered into multi-year negotiations with the government of Honduras? Taken advantage of a clause in the Honduras-Kuwait Treaty Of Reciprocal Investment guaranteeing them their right to pursue their vision unmolested? Raised millions in venture capital and bought land on a Caribbean island to turn it into a reality?

Not Erick Brimen, and not Honduras Próspera Inc. You might have read about them last month in Bloomberg: A Private Tech City Opens For Business In Honduras. Or in NACLA: A Private Government In Honduras Moves Forward. Or FT: An Investor’s Prosperity Vision For Honduras. I read all of this and still didn’t feel like I quite understood what was going on. Then a fortuitious mistake led me to an email exchange with Trey Goff, Próspera’s extremely open and thorough Chief of Staff, who kindly let me grill him on all the stuff I didn’t understand.

The result is this post. It’s all the information I could collect on Próspera from basically every public source, plus some non-public ones. It’s about a private tech city and a prosperity vision and all that. But it’s also about - - - well, people talk a lot these days about “systemic change”. But usually that means something like fiddling with tax rates or ending the filibuster. What if you could actually change the system? Say “this system we have, the one that’s letting all these people starve and suffer violence and die of preventable diseases - I don’t care for it. Let’s try something else”? Yes, this is about startup governments and investment opportunities and blah blah blah, but it’s also about trying to fight global poverty by radically changing the rules of the game that makes it possible.

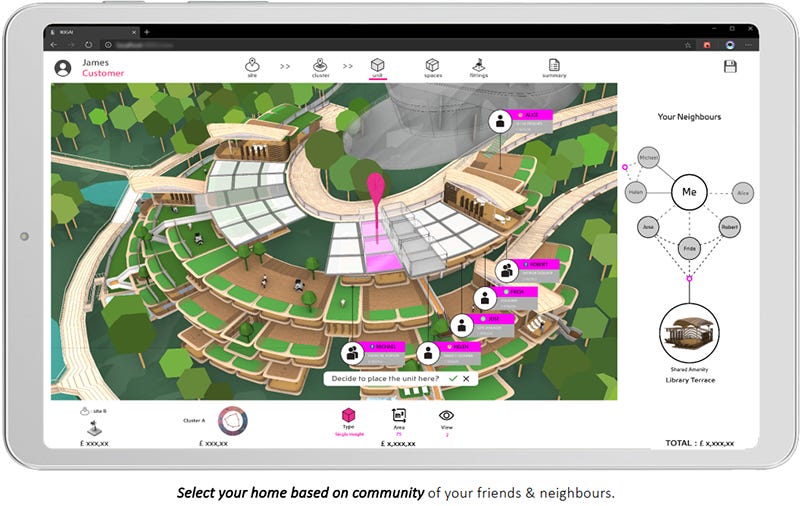

Also, it will look like this:

So, starting from the beginning:

1. What is this? What’s a ZEDE? What’s going on? Where am I?

In 2009, Nobel-winning economist Paul Romer proposed a new type of governance structure. Underdeveloped countries looking for an economic boost could donate territory to some entity considered non-corrupt and skilled at governance - for example, a successful country like Switzerland. The recipient entity would govern the territory as effectively as it could, bringing improved human rights and economic growth.

If this went well, it could be win-win-win. The region’s citizens would get good governance, safety and wealth. The underdeveloped donor country would get to skim a little off the top as taxes, plus the downstream benefits of having a well-developed economic hub in their country. And the successful recipient country would get bragging rights, investment opportunities, and comparatively cheap labor.

Honduras - with 70% of its population in poverty, the 5th highest murder rate in the world, and a political system widely recognized as corrupt and dysfunctional - was running low on options. They approached Romer and expressed interest in his idea. Together, Romer and Honduran officials developed the ZEDE (Spanish acronym for “Zone for Employment and Economic Development”), a generic model for creating special economic zones (“charter cities”) within Honduras.

1.1. Sounds nice and straightforward, I guess?

Nope, the original implementation of the ZEDE law was a disaster.

In 2009, Honduras’ leftist-ish President Manuel Zelaya proposed a referendum to change the Constitution, which his opponents interpreted as a plot to remove term limits and rule indefinitely. The Supreme Court ruled against him, Zelaya ordered the military to assist in holding the referendum anyway, and the military held a coup instead. They appointed the next person in the line of succession the interim president, then held tense elections which were partially boycotted by Zelaya supporters and of debated legitimacy. Conservative candidate Porfirio Lobo Sosa won and became president. Lobo’s chief of staff Octavio Sanchez stumbled upon the TED talk where Romer discussed charter cities and invited him to Honduras for negotiations.

Lobo’s party controlled Congress and got a charter city law passed. After this the story gets kind of murky. Paul Romer’s version was that they appointed him head of a Transparency Committee to make sure that whatever happened was in the best interests of Honduras, then started negotiating with a company called MKG Group without telling him. Upset at the opacity, and also at the negotiations themselves (he preferred having a foreign country administer the zones, not a private corporation), he resigned in protest. Honduras’ version is that Romer was never appointed head of anything and there was no Transparency Committee.

Attention turned to a definitely-existing group called the Committee For Best Practices (CAMP in Spanish) which was handling the day-to-day negotiations. But its members seemed to have been hand-picked to raise eyebrows. They included Ronald Reagan’s adopted son, the foreign minister of Oman, US low tax campaigner Grover Norquist, and - in case there was a single conspiracy theorist anywhere in the world not already on high alert - a member of the Habsburg family. I would say this raises a lot of questions, but really the only question anyone had at the time was “what?”

In the midst of all this, the Honduran Supreme Court struck down the charter city law 4-1 because they thought it threatened Honduras’ sovereignty.

This became part of a broader conflict in Honduran politics, which came to a head after the Supreme Court struck down a major police reform bill. Congress fired the four anti-government Supreme Court justices and replaced them with pro-government ones; opinions on the constitutionality of the move range from unclear to extremely skeptical. There was a big crisis for a while, various factions accused various other factions of plotting coups, but the government made it through. Three years later, they tried again with a ZEDE law, this one slightly amended to make it clear that the areas were still ultimately under Honduran sovereignty. The new packed-with-government-supporters Supreme Court pronounced it okay, and the law passed with the support of 78% (!) of Congress. They dismissed the old CAMP members and replaced them with people apparently inoffensive enough that nobody’s reported on who they are (I think one of them might be this guy).

After various other failed projects and false starts, we come to Próspera and the present.

1.2. Could this work?

Maybe.

Proponents point out that the idea of a ZEDE or charter city is similar to (in fact, stronger than) the idea of a special economic zone, which transformed the cities of Shenzhen in China and Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

You could tell similar stories about the success of Hong Kong and Singapore, two other polities with little to recommend themselves other than a different and more competent regime than the surrounding regions.

The idea behind charter cities is: Shenzhen, Dubai, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the rest of the rich world aren’t rich because their citizens are morally superior to those of their poorer neighbors. They’re rich because they have better legal systems, less corruption, stronger rule of law, and more competent administrators.

One reason Honduras is poor could be because it’s hard to start a business there, with long delays and plenty of opportunities for officials to demand bribes. One of Próspera’s top priorities is making it easier (source)

One reason Honduras is poor could be because it’s hard to start a business there, with long delays and plenty of opportunities for officials to demand bribes. One of Próspera’s top priorities is making it easier (source)

And poor countries don’t have corruption, crime, and incompetence because they choose to. They have those things because vested interests, zero-sum games, and poor education make it hard to improve things. If you could get part of a poor country to be under a rich-country-style government, it too could get rich the same way all those other places did.

Honduras allowed ZEDEs in order test this hypothesis and see if it offered a radical solution to poverty.

2. So what is Próspera?

Próspera is Honduras’ first ZEDE.

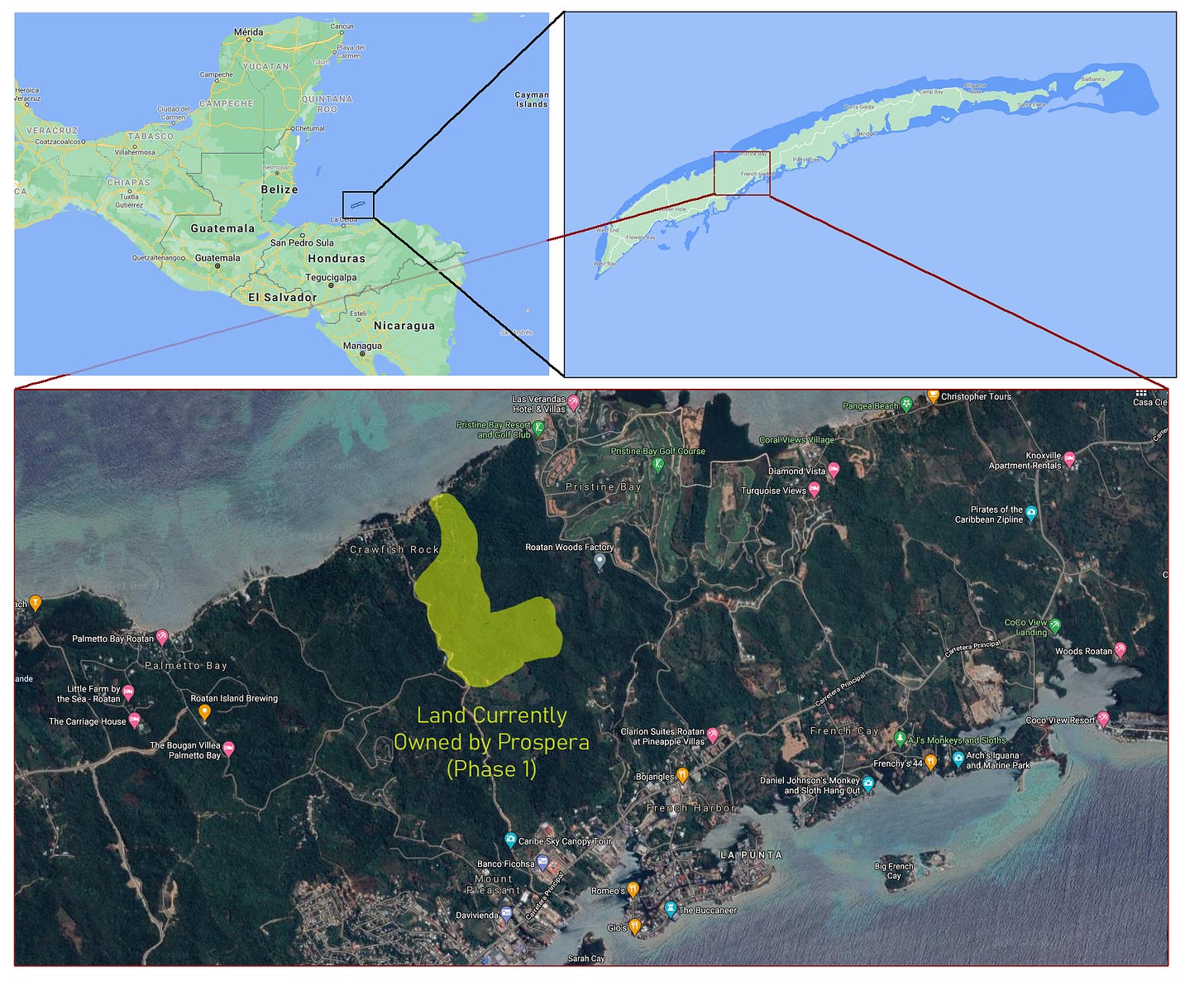

In one sense, Próspera is a 58 acre tract of unoccupied land on the island of Roatan, between a fishing village and a golf course. 58 acres is small; the nearby golf course is bigger.

If I can’t be within driving distance of Daniel Johnson’s Monkey And Sloth Hangout, I don’t want to be a part of your revolution.

If I can’t be within driving distance of Daniel Johnson’s Monkey And Sloth Hangout, I don’t want to be a part of your revolution.

So far there are three buildings on the land. They’re called the Beta Buildings, because they’re a beta test of whether people could actually build things under Próspera’s building code.

Right now this is just a sort of testbed. Eventually, Próspera plans to buy up most of the land between Palmetto Bay and the golf course (though not the area marked Crawfish Rock, which is already a separate town). That would make it about a square mile in size - a little smaller than New York’s Central Park.

But that’s only the beginning. Próspera’s not a place, it’s a platform. It’s a government with a charter, laws, legislators, officials, contracts, partnerships, etc. Anywhere can become part of Próspera - if someone has land in a totally different part of Honduras and wants to be part of Próspera they can. So far this one tract on Roatan is the only place that’s signed on, but that could change.

The Prósperans use the metaphor of a string of pearls. They expect to eventually control several noncontiguous enclaves within Honduras, the same way the US controls the contiguous 48 states, Hawaii, and Alaska, separated by ocean and foreign territory but still part of the same structure.

What’s to stop this from getting really weird? Can I have my house be in Próspera while my neighbor’s house is in regular Honduras? My kitchen in Próspera but my dining room in regular Honduras? I asked Trey, who said HPI has to guarantee provision of services to everywhere within Próspera; they wouldn’t expect providing services to somebody’s dining room to be worth it, and so they would turn down those kinds of frivolous applicants. Their plan is for a network of hubs, each city-sized and relatively convenient to provide for. They’ve already selected an area near the city of La Ceiba as their first satellite, and eventually want to expand across Honduras’ north coast.

Location of Roatan (current Próspera hub) and La Ceiba (likely future hub) within Honduras.

Location of Roatan (current Próspera hub) and La Ceiba (likely future hub) within Honduras.

Aren’t these a bit far away from each other? Wouldn’t it be hard to run a single polity on so many unconnected islands and enclaves? From the white paper:

Próspera is well versed on the myriad environmental, climate, and humanitarian concerns with automobile traffic. As such, Próspera hopes to enable the creation of the world’s first truly affordable and safe air taxi system between its various Prosperity Hubs through the use of VTOL drones.

Air taxi image taken from here, this is not from Prósperan promotional material or necessarily what they want theirs to look like.

Air taxi image taken from here, this is not from Prósperan promotional material or necessarily what they want theirs to look like.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, remember that right now, in the real world, it’s a tract of land somewhat smaller than a golf course, with approximately three buildings on it. The main building looks like this:

3. Who’s doing this?

In the original plan, charter cities would be governed by some respected and competent foreign power like Switzerland. That fell apart for various reasons (worries about national sovereignty and colonialism, no sign Switzerland actually wanted to help) and the new version is that they’ll be governed by a corporation full of visionaries and experts and other hopefully non-corrupt people. The corporation will only make money if the ZEDE becomes economically productive, corporations seem to like making money, so in theory this gives them an incentive to govern wisely.

The particular corporation involved in Próspera is Honduras Próspera Inc (after this: HPI), and its founder and CEO is Erick Brimen.

Brimen comes from Venezuela, where he briefly flirted with socialism and Chavismo as a teenager before “reality…opened my eyes to just how wrong I was”. He emigrated to the United States, entered finance, rose through the ranks, founded an insurance company in Colombia, and eventually started a “social impact investing” corporation called NEWay Capital to promote growth in Latin America. Próspera started out as one of NEWay’s projects and quickly grew into a separate and more ambitious company.

NEWay is barely five years old, has single-digit to low double-digit employees, and seems to deal with sums of money in the single-digit millions. They hardly seem like the sort of people that you would expect to see founding their own city. Is there anybody else involved?

HPI is getting some funding from Pronomos Capital, who are exactly the sort of people you would expect to see founding their own city. Pronomos is a group of Silicon Valley libertarians interested in competitive governance; their site predicts “crowd choice in governance providers, new startup societies approved by existing states, and completely new developments in unclaimed areas such as the high seas or celestial bodies”. Some of them are veterans of the Seasteading Institute, who wanted to create charter cities on floating platforms in international waters. Pronomos is run by former SI head Patri Friedman (grandson of Milton Friedman, son of David Friedman), and their advisors include cryptocurrency mogul / VC / outspoken libertarian Balaji Srinivasan, legendary venture capitalist Naval Ravikant, and lots of other apparently rich and famous people who I know less about. I think we would all be disappointed in Peter Thiel if he were not involved in this somehow, and it looks like in fact he’s a major Pronomos funder.

But as far as I can tell, the big-name billionaires are only providing the money. Weird as it sounds, Próspera is mostly the project of a small company, started by a Venezuelan guy who’s really passionate about helping Latin America.

3.1. Do they, uh, have a track record of building successful cities?

Actually, some of them do! They’ve collected advisors from some of the most influential private city projects of the past few decades.

Jeff Singer is the former CEO of Dubai International Financial Center Authority, the charter-city-like legal zone at the heart of Dubai; Chirag Shah is another member of Dubai’s executive team. During their administration, Dubai got the world’s tallest building, the world’s largest shopping mall, the world’s largest theme park, the world’s busiest international travel hub, the world’s largest painting, and the world’s largest chocolate sculpture of the world’s tallest building in the world’s busiest international travel hub.

44.2 feet tall, in case you were wondering. Taking bets on which will come first: the world’s largest painting of the world’s largest chocolate sculpture, or the world’s largest chocolate sculpture of the world’s largest painting.

44.2 feet tall, in case you were wondering. Taking bets on which will come first: the world’s largest painting of the world’s largest chocolate sculpture, or the world’s largest chocolate sculpture of the world’s largest painting.

Oliver Porter is the architect of the Sandy Springs model, named after the city of Sandy Springs, Georgia. This is an interesting rabbit hole in itself - Sandy Springs incorporated in a hurry, didn’t have time to create its own city services, hired private corporations to do everything, then liked it so much that they advertised themselves as a libertarian paradise and a model for everyone else to follow (though see here for another perspective).

Tom Murcott was an investment officer for Songdo, a South Korean charter city which now has 50,000 people, a thousand-foot-tall skyscraper, the headquarters of the UN’s Green Climate Fund, and a pneumatic waste disposal system - instead of leaving cans out for the garbage truck, you throw your trash directly into pressurized tubes that suck it to the recycling center or incinerator.

The HPI team also has a bunch of lawyers, consultants, diplomats, architects, and enterpreneurs. So, so many entrepreneurs.

5. Who will live in Próspera?

Próspera expects 10,000 residents by 2025.

They’re especially focusing on Honduran professionals and remote workers - the more remote, the easier a time they’ll have moving to a new city on an island. But they’re also interested in poorer Hondurans looking for construction and service jobs, and expats after a slice of paradise on a tropical beach.

Interested? All you need to do is sign the social contract, pay the membership fee, get Honduran residency (they promise it’s pretty easy, and they have lawyers who can help) and you’re good to go.

Wait, sign the social contract? Yes. Contra your Political Science professor, there’s a literal social contract which you literally sign (officially: “Agreement Of Coexistence…which stipulates that the resident is explicitly, freely, and voluntarily consenting to the governance structures, rulemaking systems, and authority of Próspera”).

And wait, membership fee? Yes. It’s $260/year for Hondurans, $1300 for foreigners, maybe more for corporations. This is separate from normal taxes, and goes to HPI as part of their compensation for running the ZEDE.

Are people actually up for this? HPI says a thousand Hondurans have already applied. Since there’s currently only one building complex in Próspera, it’s safe to say that the supply of interested residents will be exceeding demand for a long time.

In case demand ever exceeds supply, HPI is already reaching out to NGOs that work with Honduran refugees trying to illegally immigrate to America. They plan to see if they can convince these people to legally immigrate to Próspera instead (“Hey, we heard you liked jobs and capitalism…”)

We’re opening up the Próspera Talent Bank. Any Honduran who is looking for a better life and a better job IN HONDURAS should submit his/her information: info.prospera.hn/talent We’re at just under 15 new jobs… if you want to be among the first 100, move fast! #hondurasprospera

info.prospera.hnPróspera Talent - EN11:02 PM ∙ Aug 3, 2020

info.prospera.hnPróspera Talent - EN11:02 PM ∙ Aug 3, 2020

Interested parties who don’t want to move to Roatan can seek “virtual residency” / “e-residency”, a concept pioneered by Estonia in 2014. This mostly allows virtual residents to set up companies in Próspera, governed by Prósperan law. In keeping with their usual modus operandi, HPI has already hired Ott Vatter, the leader of the Estonian project, to design their system.

6. Will Próspera be a libertarian / anarcho-capitalist utopia?

Sort of but not really.

The people behind Próspera are mostly libertarians, but they’re trying to avoid using the word “libertarian” too much when talking about their project. Partly because the libertarian brand scares people. But partly because their vision is more complicated than just small government.

Charter cities fall into an awkward crack in libertarian ideology. Almost every libertarian agrees that you can make rules (even arbitrary rules) about what people can do on your own property, and anyone who wants to stay on your property has to follow your rules. But what’s the difference between that, versus a government “owning” its territory and making rules for its citizens? In practice the difference is that going in someone’s house - or even their golf course - is a choice you made, and they have clear title of ownership. But being in a country happens involuntarily, and the President doesn’t “own” America in the same way an ordinary person might own a house.

But if someone did own an entire city, and you chose to be in that city, theoretically they should be able to make whatever laws they wanted, and not even the most zealous libertarian could protest. The issue hadn’t really come up before. But here we are.

Próspera is erring on the side of small government, because that’s what they expect will work best. But their overriding motive is making their city a nice place to live and work, and when small government conflicts with that, the city usually wins.

So for example, when you buy land in Próspera, you’ll have to sign a Covenant Restricting Vice Industry Uses - ie you can’t turn your house into a joint brothel+casino and do unethical medical experiments in the basement. Even the strictest libertarian has to admit this is fair; if you sign a contract, you’ve got to follow it. But you can tell HPI plans to have the town be ship-shape, well-organized, and family-friendly, instead of the sort of Wild West vibe some people associate libertarianism with.

Also, Próspera remains bound by several Honduran laws that Honduras refuses to exempt them from, including laws against abortion, euthanasia, and most gun ownership.

6.1. But they’ll at least have really low taxes, right?

The lowest in the world.

The Próspera Charter declares that income taxes cannot exceed 10%; anyone who wants to raise taxes above that will have to pass a full constitutional amendment in a system deliberately designed to be hard to change. There are also some other minor taxes, but the Charter says that (after certain conditions are met) total taxes may never exceed 7.5% of GDP, and total debt may not exceed 20% of GDP (with various specifications and caveats). From HPI documentation:

This is a key improvement upon the American system, as unlimited debt can potentially lead to untenable fiscal situations which threaten the economic health, stability, and shared prosperity of the jurisdiction

Where do the taxes go?

- 12% go to Honduras, as their incentive for allowing ZEDEs at all

- 44% go to the General Service Provider, a private company that handles things like sanitation and power. This will probably be an HPI subsidiary which subcontracts out to Jacobs Engineering, the same company that did a lot of the work in Sandy Springs.

- 44% go to the Próspera municipal government, to handle whatever services they can’t subcontract out.

How does HPI make money? They get a cut of the membership fees and the General Service Provider money, but their real cash cow is probably land development. They buy empty land, develop it into a thriving city, then sell it to people who want to live in thriving cities at a huge markup. The more thriving the city, the higher the land value, and the more money HPI makes - which they think puts the incentives in the right place.

7.Okay, but what will Próspera be like?

So some businesspeople have gotten a once-in-a-lifetime chance to design a utopian city of the future from the ground up. The Honduras government will let them do great innovative things. They’re incentivized to do great innovative things. They have enough money and talent to be able to do great innovative things. What particular kinds of great innovative things are they planning to do?

Going through the list:

7.1. What will the houses in Próspera be like?

Modular, customizable, community-oriented, and beautiful.

Patrick Schumacher is the Principal Architect of Zaha Hadid, a world-famous architectural firm that designed eg Beijing International Airport and the London Olympics’ Aquatics Center. He’s won some of architecture’s most prestigious prizes, but also faced controversy over views his Wikipedia page describes as “aligned with anarcho-capitalism in favour of complete decentralisation and radical privatisation of all aspects of architecture, planning and development”. He recently lost a court case over ownership of his architecture company, and…wait, haven’t I read this Ayn Rand book before?

Anyway, he’s embraced Próspera as a laboratory for some of his wilder ideas, and the results are pretty stunning:

Trey: “Building codes and rules around aesthetics and setbacks and whatnot prohibited them from designing low cost, beautiful Zaha Hadid style structures prior to now. And without modular construction, it was impossible to get construction costs down to a reasonable number. But they’ve finally managed to pull it off, in coordination with [local startup] Circular Factory.”

Trey: “Building codes and rules around aesthetics and setbacks and whatnot prohibited them from designing low cost, beautiful Zaha Hadid style structures prior to now. And without modular construction, it was impossible to get construction costs down to a reasonable number. But they’ve finally managed to pull it off, in coordination with [local startup] Circular Factory.”

Drones sold separately. I think. Actually, scratch that, who even knows anymore?

Drones sold separately. I think. Actually, scratch that, who even knows anymore?

Próspera also promises an unprecedented level of customization. The houses are modular enough that you can design yours however you want. I haven’t been able to get access to the real program (called “the Configurator”) yet, but here are some apparent screenshots:

How much will these cost? Trey estimates a starting price of $70K to buy or $450 - $600/month to rent for cheaper units. In a podcast, Erick Brimen gave some slightly different estimates for more expensive homes: $3750/m^2, with sizes ranging from 40 m^2 (small apartment) to 250 m^2 (large four bedroom house) - which would suggest prices from $150,000 to $950,000.

I get the impression that the pictures above are the Prósperan equivalent of apartment buildings; I’m not sure what their single-family houses are like. But Próspera is also interested in serving non-traditional living arrangements - group houses, co-living spaces, whole communities uprooting themselves and relocating to somewhere in Próspera they’ve customized for their needs.

Meanwhile, in much of the US it’s still illegal for unrelated people to live together.

Meanwhile, in much of the US it’s still illegal for unrelated people to live together.

Making big promises and glossy images is easy, but for the record, Trey says that “[these] renders should reflect the reality of the 58 acres by end of 2022”.

What about the poorest Honduran laborers who can’t afford $450/month? Trey writes:

For blue collar laborers under even tighter economic circumstances, LAVA Architects in partnership with a Honduran architect have created something we call the Beta Residencies (for now), which can be built for less than $40k and in less than 60 days. These are specifically designed for very low-income Hondurans to be able to move in to Próspera alongside the wealthy expats, as urban planning literature shows having a diverse cross section of class and culture is important for community cohesion, especially early on when the community is just forming. Some of them are already built.

Here they are:

7.2. What will the education system be like?

From their white paper:

If some students are capable of learning two years of standard school mathematics in one year whereas other students can only learn half a year of standard mathematics in one year, personalized learning systems will allow schools to customize education for the needs of individual students. “Competency-based” refers to the fact that schools should focus on whether or not students have mastered the academic content rather than how many credit hours they have taken of a subject. The fact is some students are very fast in some subjects and slow in others, some students are fast in all subjects, and some students are slow in all subjects. Learning systems should reflect the diversity of student interests and abilities.

As examples of what they like, they list every successful private school ever, including ones whose philosophies contradict each other, like Montessori and No Excuses (though I was also recently accused of doing this, so whatever).

Trey says they’re negotiating with someone involved in Montessori schools to bring one to Próspera as their first educational institution.

In terms of secondary education, they had a deal with Technical University of Munich, a very well regarded German university, but it looks like German leftists pressured them into withdrawing. Currently they are investigating a partnership with Universidad Francisco Marroquin, a libertarian university in Guatemala City which (for example) has a “Ludwig von Mises library [which] has 100,000 visitors annually and is the most extensive collection of works on liberty in Latin America”, and whose alumni include eg one of Julian Assange’s defense lawyers.

7.3. What will the health care system be like?

Próspera currently advertises a partnership with CEMESA Hospital, a nice and completely normal local hospital in Roatan that would be well-placed to expand into Próspera. But they also want to become a center of medical tourism, ie people going to foreign countries to get better or more affordable medical care than is available at home. Their Master Plan hopes to have a medical center like this available within the first few years.

But let’s get to what I know you’re all here for - medical licensing policy. Próspera plans to be the first polity to allow complete medical reciprocity with all developed nations (plus Honduras). That means if you’re an American/French/Japanese/etc doctor with a valid American/French/Japanese/etc medical license, you are licensed to practice medicine in Próspera.

This policy is close to my heart, because like many people I’ve had Uber drivers who were doctors back in their home countries. They’re stuck driving Ubers because the US insists that nobody - not British doctors, not Canadian doctors, nobody - can work in the US unless they repeat their last four years of training in an American hospital. American hospitals don’t have many training positions, and reserve the ones they do have for American med students, so most of them can’t do it. Meanwhile, my patients complain of having to wait months to get a desperately-needed appointment, and the hospitals just say “well, there aren’t enough doctors”. There are, they’re just all driving Ubers because of regulatory failure! I’m not sure Próspera goes far enough - a lot of the real gains would come from allowing Indian or Iranian doctors - but go further than anywhere else.

Likewise, Próspera has 100% drug approval reciprocity. If a drug has been approved in an OECD country (eg by the FDA), it’s approved in Próspera. Again, close to my heart. Amisulpride is a great antipsychotic, probably better then most of the ones we use here. It’s approved in Europe, the UK, Australia, Israel, etc, where many studies have shown it’s safe and effective. Because none of those studies were done in the US, the FDA refuses to approve it here, and has demanded several hundred million dollars worth of more studies, which the company involved has chosen not to do (an injectable version was recently approved for nausea, but can’t be easily used for psychosis). Meanwhile, bupropion (“Wellbutrin”), the fourth-most prescribed antidepressant in the US, isn’t approved for depression in Britain; the subset of patients who respond to this medication and nothing else are out of luck. Próspera will be one of the only places in the world where patients will have access to amisulpride, bupropion, and all the other medications that one country or another is restricting because “it wasn’t invented here”.

7.3.1. How will hospitals and medical practices be regulated?

The same way as everything else in Próspera - pick a country or get insurance.

You can read the details in the Industrial Regulation Statute starting on page 317 of their law code , but I think the basics of “pick a country” are - you can choose what country’s regulations you want to operate under, with your options being Honduras or a list of Best Practice Peer Countries including:

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Dubai, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Hong Kong, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Singapore, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States of America

So if I open a medical practice in Próspera, I can look through everybody’s medical regulation laws, decide Norway’s laws suit my purposes best, and choose to be bound by the Norwegian regulatory code. Then I have to follow all the laws carefully like a good Norwegian. If I get in trouble, any disputes between me and my patients will be settled by Norwegian law.

It actually goes further than this - you can choose to be in a particular location within a Best Practice Peer Country. Trey uses the example of a developer choosing to build a skyscraper using the laws of Houston, Texas. Since Houston is in America, a Best Practice Peer Country, the developer will be legally protected as long as they conform to Houston’s building regulations.

And if you don’t like any country’s regulations, but you’re confident in your ability to operate safely, you can take your chances. Anyone who doesn’t like what you’re doing can sue you under common law for any damage you cause, and you won’t have “I was following the regulations” as a defense.

(speaking of suing people, the law code seems to cap damages from medical malpractice lawsuits at $250,000, which is a defensible choice, but sure not the direction that the US has gone here.)

Everyone operating in Próspera will need insurance for any damages caused by their activities. This should be easy and cheap to get if you’re following strict regulations, harder and more expensive if you’re following lax regulations, and potentially prohibitive if you’re not following any regulations at all. The city will ensure most normal activities, but anyone who wants to do an abnormal activity - or shop around for a cheaper price - can contract with a private insurer instead.

The idea is to put the burden on insurance companies to figure out whether an industry is safe or dangerous. But it also gives companies a “default yes” regulatory option. If you invent the world’s safest ultralight plane in the US, you still have to comply with various burdensome regulations about how you can use it. If you invent the world’s safest ultralight plane in Próspera, you can prove to some insurance company that it really is as safe as you say, they’ll insure it for relatively cheap, and then you can fly it to your heart’s content. If it crashes into someone’s house, the insurance company will pay damages. If it kills someone, the insurance company will pay a lot of damages. I hope Próspera has a good way of calculating how much.

What if a regulatory issue can’t be expressed financially? I asked Trey about human genetic engineering. He said that extreme or irresponsible forms of medical experimentation will probably be banned by Honduran law or international law or something. If they’re not, he expects that insurance companies will keep their distance. If they don’t, he expects they’ll find a way to ban it anyway, for PR reasons if nothing else.

7.4. What are property rights like?

3D, possibly on the blockchain.

Prósperan property is sold in three dimension voxels, eg 1m x 1m x 1m cubes, which is supposed to solve “air rights” debates once and for all. The idea is: imagine I have a house with a nice view of the beach, but my neighbor right in front of me wants to build a tower that blocks my view. Can he do it? In the US, the answer is “depends what happens after ten years of lawsuits and city council meetings”. In Próspera, the answer is “depends who owns the voxels the tower is going through.”

So if I want to prevent my neighbor from building a tower and blocking my view, I can buy the air above his house that the tower would have to pass through; then if my neighbor builds there, he’s trespassing on my property. But if my neighbor wants to buy a house and make sure he has the option to expand it into a tower five years later, he can buy the air above his house along with the ground, and then nobody can tell him what to do on his own property.

In practice, this is going to look more like Próspera selling everybody ground-level voxels, then agreeing to sell or not sell higher-up voxels depending on whether they want to “zone” land for higher-density construction.

What happens if the person who owns the base of a skyscraper wants to raze it, but the person who owns the fifth floor doesn’t want it razed? I’m not sure, but other jurisdictions already do something like this (New York City has a hackish partially 3D property rights system) so probably someone’s already thought about it.

Sun, sand, surf, and five hundred miles from the nearest NIMBY

Sun, sand, surf, and five hundred miles from the nearest NIMBY

Though it’s just a throwaway sentence in one of their more speculative documents, they also mention:

Land backed tokens: One way to capitalize and fund the purchase and development of land is through the use of a land backed crypto token. In effect, anyone in the world could buy one of the tokens issued for a specific plot of land. This capital would then be used to purchase and develop the land, with a secondary market enabling early movers to profit as the development grows and with [HPI] or some other financial partner potentially buying all the tokens back at the successful development of the lot. This would powerfully democratize land development away from the wealthy and open the space up to everyone else.

7.5: What’s the government?

Garrett Jones famously recommended 10% less democracy . Próspera goes further: 44% less democracy. The city will be governed by a Council of nine people, of whom five are elected and four appointed by HPI.

(right now everyone is appointed by HPI because no one lives there, but there are various provisions for gradually giving residents more of a voice as more of them move in, and eventually five Council members will be elected)

But that’s still kind of democratic, right? Majority democratic? Yes, but the Council requires 66% majority to do anything. The five democratically-elected members can’t do anything without at least one HPI member in support.

But HPI also can’t do anything without some democratic members in support, right? Yes, but HPI has already written all the laws the way they want them. They can’t change anything without at least some democratic support, but they expect to be pretty happy even if they have to keep everything the same.

(also, one assumes that the four HPI members will vote as a bloc on issues important to the company, but the democratically elected members will be split among various parties and philosophies in the tradition of democratic elections everywhere. As long as 2/5 democratically elected members vote with HPI, HPI gets what it wants).

Other parts of the government follow the same principle: impressively democratic on the surface, unlikely to rock the boat in practice. For example, if the general population disagree with a law passed by the Council, they can overturn it in a referendum with a simple 50% majority. But the offer only applies within seven days of the law being passed (Trey insists that Próspera’s e-governance platform will be so good that it will be easy to know what’s going on, start a referendum, and finish voting within a seven day period). Even after the seven days, the public can repeal any law. But now it requires a 66% majority, and also this process can only repeal laws, not add them.

The most drastic check on the government: once Próspera has 100,000 residents (so realistically a long time from now, if the experiment is very successful), they can hold a referendum where 51% majority can change anything about the charter, including kicking HPI out entirely and becoming a direct democracy, or rejoining the rest of Honduras, or anything. Trey says he hopes it never gets this far, that he can’t imagine failing so badly that the residents would want to kick them out, and that this was added in case somehow Próspera gets gobbled up by some other company that does a much worse job than HPI intends to. But also , the referendum requires support from 51% of eligible voters , not 51% of the people who turn out to vote. For comparison, in the most lopsided presidential election in modern US history, FDR winning his second term with 523 electoral votes to his opponent’s 8, only 35% of eligible voters voted for FDR.

Other interesting Próspera government facts: candidates for the 5 democratically-elected seats must have “successful business experience or comparable strong management or leadership experience”, and be of “high ethical standards”. If you think a candidate is inexperienced or has a history of shady behavior, you can challenge their candidacy in court.

7.5.1: What about the judiciary?

Honduras requires Próspera to use the regular Honduran criminal justice system, but they can have their own civil law. Próspera’s civil law is based around arbitration. When signing a contract, you can choose who will arbitrate your contract in case of disagreements. If you don’t choose, you default to the Próspera Arbitration Center.

I don’t envy the PAC if they have adjudicate disputes involving, say, a doctor who has chosen to be regulated by the medical code of Norway suing her office building regulated by the laws of Houston, Texas. But they’re trying to rise to the occasion: their arbiters include a former Arizona Supreme Court judge, the head of the Cato Institute’s Center for Constitutional Studies, and “the first Chilean lawyer to obtain permission from the Berlin Bar Association to act as a legal advisor in Chilean law in Germany”, which I guess sounds like the level of convolutedness you would need to be experienced in to make this work.

7.6. What if I move to this weird charter city that’s schismed from the rest of Honduras, and I decide I don’t like it? Am I allowed to meta-schism from it and form my own even weirder, charter-er city?

Allowed, encouraged, and your right to do so is enshrined into law!

Trey writes:

We wanted to allow for the creation of internal competitive pressures on ourselves. As such, by the Charter, any community can create a community interest declaration and displace the GSP entirely within the limits of their community. It’s a miniature competitive jurisdiction within the [larger] Próspera jurisdiction. It still has to comply with Próspera statutes, but is free to make its own rules just like an HOA does, and is free to hire it’s own security like many private developments around the world do.

Unlike anywhere else in the world, it also displaces the rest of the jurisdictions’ provision of services in that area. So if an intrepid individual wants to create a better community with better rules and administration than we have, we invite them to come do it! Test drive your Marxist commune in Próspera! Maybe it will work this time. If it does, then people can move out of the rest of Próspera and into your little community, and the ZEDE will have to adapt its meta institutions accordingly.

This mostly applies to provision of services (eg electricity, sanitation, policing). But partly that’s because Próspera already provides optionality in other areas. For example, by default contracts disputes are resolved under Prósperan law by the Próspera Arbitration Center, but you and your fellow commune-members can agree that all of your contracts will be resolved under your own private law that you made up, by some other arbiter you selected. Most of the schools will be private anyway, but if your commune wants to have its own separate private school, nobody can stop you there either.

8. What stops Honduras from pulling the rug out from under them after they’re successful?

A timely question, given recent news about Hong Kong. Its unique position outside the Chinese system helped it grow rich and important, China promised to preserve that position, and - once it became inconvenient to China, they reneged on their promise and reapplied Chinese law. Why couldn’t the same happen here?

The law enabling ZEDEs was passed as an amendment to the Honduran Constitution, which would require a 66% majority to overrule (it was passed with a 78% majority, so that would require an overwhelming turn against it). The law also says that even if repealed, it will take ten years for the repeal to take effect (I don’t know if this is legal or enforceable). Ten years is longer than a Honduran election cycle, so you would need two consecutive governments to agree to repeal it.

Próspera says they are “guaranteed by international treaty”. The particular treaty involved is the Honduras-Kuwait Treaty For Reciprocal Investment (link in Spanish), in which I think Honduras tells Kuwait that they should feel comfortable investing in ZEDEs because Honduras promises not to get rid of them for 50 years. I don’t have anywhere near the understanding of international law I would need to know if this is actually binding. Could a future ZEDE-hostile Honduran Congress repeal this treaty? Would that damage their international reputation? Precipitate the Great Honduras-Kuwait War Of 2036?

Finally, what would Honduras’ incentive be? They went into this hoping that ZEDEs would be economically productive, and this would benefit the rest of Honduras and let them skim a little off the top. If ZEDEs actually become economically productive, letting that benefit the rest of Honduras and skimming a little off the top still seems like their best bet. Sure, if push came to shove, they could take over the ZEDE by military force. But that would be killing the goose that lays golden eggs. China didn’t take over Hong Kong because they wanted its money. They already had as much of its money as they cared to take. They took over Hong Kong because they wanted to maintain autocratic rule, and having a successful democracy inside their borders was too awkward. The Charter Cities Institute’s blog talks about this further.

9. Is anyone else doing anything like this?

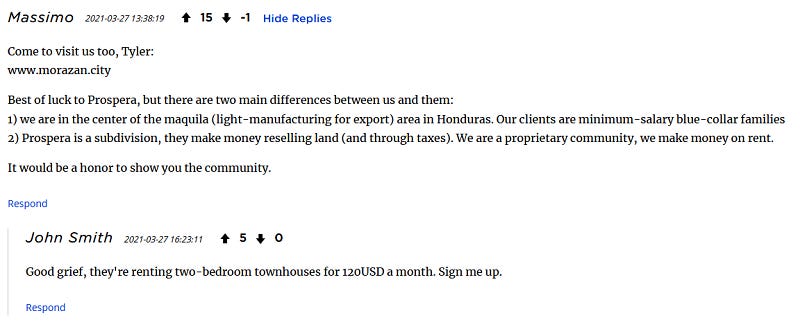

There’s another ZEDE project called Ciudad Morazán, on the Honduran mainland. They are almost exactly the same size - 59 acres. They’re less flashy and ideological and publicity-seeking than Próspera. They just seems to want to build a nice neighborhood in the suburbs of Choloma, Honduras. Looking at their website, they talk a lot about crime and “freedom from fear”. I think at least part of their business case is to be able to give poorer Hondurans a place to live that has private security and good policing, which would be a big attraction in such a violence-ridden country. They promise that:

“Ciudad Morazán offers freedom of fear because it is a private venture, created to make money. The developer has to provide its clients the best possible environment in order to rent the spaces of the community. The developer will not keep in its payroll corrupt or ill-mannered security guards. It will not rent accommodations to criminals. The houses are built to last and are resistant to nature events…Residents that engage in criminal activities will be swiftly turned over to police authorities. People that do not follow the rules of coexistence or are a nuisance to their fellow residents will be denied the renewal of the rent. We will be strict in the application of the rules, because it is the only way to guarantee everybody the best possible place to develop as responsible, happy and fulfilled individuals.”

Taken from https://www.morazan.city/residence/ . A police car in every pot!

Taken from https://www.morazan.city/residence/ . A police car in every pot!

I’d originally thought these people were more grounded and less ideological than Próspera - where Próspera’s documentation has wild dreams of 3D property rights and land-backed crypto tokens, Ciudad Morazan’s has page after page diagramming how the sewer system is going to work. Just normal, hard-headed businesspeople doing business, right?

But I recently spotted their CEO/Council Secretary in the Marginal Revolution comments section, a sure sign of a deranged mind.

Still, they have a lot of advantages over Próspera. For one thing, their ambitions are lower. For another, they’re run by a huge company, Centro American Consulting & Capital, with “revenues…around $800M per year”. For another, nobody seems to have noticed them enough to get angry yet.

Speaking of which…

10. Will Próspera expropriate land?

There’s a whole small industry of anti-Próspera activism, almost all of which centers around the same concerns: Próspera is going to steal people’s land, Próspera will nonconsensually annex the surrounding towns, thousands of people will be forced into Próspera against their will, Próspera will evict indigenous people from their own territory, then sell it back to them at sky-high prices.

To be completely fair to these people, this is usually a good starting assumption whenever something is happening in Honduras. Honduras’ North Bay - the area where Próspera will be starting off - has a long and ugly history of evicting natives for big development projects.

The concerns around Próspera mirror the case of Randy Jorgensen, a Canadian porn mogul, who founded a chain of Honduran tourist resorts. He expropriated land from native communities, especially a group called the Garifuna who are descended from escaped African slaves. Jorgensen and his supporters in the Honduran government did use violence (and other tactics, like cutting off basic services) to force the Garifuna off the land. It was terrible, and everyone in this part of Honduras is understandably on edge. Although there’s no connection between Jorgensen and the ZEDE, some people see them as the product of the same pro-business, pro-development tendency in Honduran government.

Próspera has tried its best to repudiate these kinds of tactics. They’ve passed an internal resolution saying it’s illegal for Próspera to ever expropriate Honduran land without the owners’ consent. With their support, the CAMP (the Honduran governing body regulating ZEDEs) has passed a Honduran resolution saying it’s illegal for ZEDEs to expropriate Honduran land. Próspera’s current territory is a completely empty site where “in order to avoid claims of expropriation (which we somehow inexplicably got tarred with anyways), we [did] title research to ensure at no point in the property title’s entire history has it ever been expropriated by the government.” Their stated policy is to only buy other empty land, from the landowner, with their consent.

The flashpoint of this conflict has been a fishing village a few hundred feet from the Próspera site called Crawfish Rock (its name is in English because Roatan was formerly a British colony and still has many English speakers). Different versions of the story are going around - according to Próspera, Crawfish Rock held a referendum on whether they wanted Próspera next door, and 90%+ voted yes. According to opponents, those people didn’t realize Próspera was a ZEDE and probably hate ZEDEs and would all be against Próspera if they understood it. This site has some more incomprehensible and contradictory information, including that

On August 10, the federation of village councils and several civic associations in Roatan released a joint statement about the unrest caused by the project, given that it went into motion without adequate community awareness or consultation […] The model city developers…sent a letter on August 20 to the residents of Crawfish Rock indicating that the village council had [since] disassociated itself from the public statement and supported the Próspera project. But no village council members signed this document.

There was a weird event which I don’t have a great perspective on, where Erick Brimen, CEO of HPI, scheduled a meeting in Crawfish Rock to explain what Próspera was and why people didn’t need to be afraid of it. The municipal government banned him from having the meeting, supposedly because of COVID. Brimen felt he was being silenced, and said that he would have the meeting outdoors and observe all social distancing guidelines but otherwise wasn’t going to back off. He held the meeting, the municipal government sent police to shut it down, and after some resistance it got shut down (see video below).

Do the Prósperans seem a little defensive about this? I think it’s warranted. The government of actual Honduras has been expropriating things right and left throughout this area for decades. This is part of the failure of Honduran governance that they’re trying to provide an alternative to. Instead of having to live in a country that expropriates your land whenever Canadian porn moguls ask them to, you could live in a libertarian paradise obsessed with property rights and rule of law. Trey says: “Land expropriation is the exact kind of governance failure Próspera exists to fix”.

But everyone keeps ignoring Honduras’ repeated and flagrant land expropriation in favor of freaking out over completely fictional land expropriation by Próspera.

10.1. Could Próspera commit human rights abuses?

Well, they say they won’t.

But they at least make a strong case. Their first argument is that the border with Honduras is about five hundred feet away. Most Prósperans will be Honduran citizens (and the few expats can probably take care of themselves). So if anyone is unhappy or feels like their rights are being violated, one of their options will be to walk five hundred feet and be back home in regular Honduras. It would be really hard for Próspera to give immigrants from elsewhere in Hondurans a life worse than normal Honduras is offering them, and still keep them in the ZEDE.

Their second argument builds on the first; HPI only makes money if lots of people live in Próspera and patronize it with their business. If they start murdering people or stealing things, you wouldn’t want to live there and you wouldn’t want to set up a business there. When Honduras’ neighbor Nicaragua brutally crushed anti-government protests, their GDP per capita decreased 10% - an unprecedented amount during peacetime - as citizens fled, businesses closed, and foreign investment rushed out. If nothing else, HPI will be trying to avoid this to protect its own bottom line.

Their third argument is that Honduras is a party to all the normal international human rights treaties, and those treaties still apply in ZEDEs like Próspera. So human rights violations remain illegal. ZEDE law says that any alleged human rights violations in Próspera go straight to international courts (though nobody has figured out exactly which international court yet). For lesser issues, Honduras is also working on a system of ZEDE courts, where people who feel ill-treated in a ZEDE can appeal to Honduras-government-run ZEDE court and have their case heard.

And also: I’m writing this post off of some internal documents I was allowed to see, but I’m summarizing them. The real documents are this same information, but constantly interrupted by a bunch of brightly-colored graphics about how sustainable and just everything will be all the time. Words like “equitable” get used like they are going out of style. They plan to have “no poverty”, “zero hunger”, “gender equality”, “reduced inequalities”, “climate action”, etc. There’s a whole formal Bill Of Rights which they say “provides stronger human rights protections than those of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights” and “is more restrictive of state power and coercion than the American Bill of Rights, with clearer and more objective language”. Just assume that whatever concerns you have, they have a brightly colored graphic that uses meticulously-crafted language to express their commitment not to do it. These documents were aimed at investors.

So if you’ve read enough Matt Levine, you know where I’m going with this: if anything bad ever happens in Próspera, you can probably sue them for securities fraud.

10.2. What’s the case against Próspera?

You can read what actual anti-Próspera people have to say here, here, and of course on Vice. But I can’t stress enough how misleading and awful most of it is.

“Imagine…” starts the first:

…you live in the most dangerous country in the world that is not in a war zone. You fear your government, and the ZEDE syndicate taking over your homeland as much as you fear the narcotics gangs…these libertarian neocolonial conquistadors’ sole aim is to eventually force all of you out of their stolen paradise, and eventually expand, swallow and exploit the most precious parts of your country and its resources….In this new ZEDE experiment the indigenous people on Roatan how have to re-apply and pay to live on the their own land.

Nobody is as afraid of ZEDEs as they are of narco-gangs. Nobody is being forced out of anywhere - they’re being offered the choice to move to a previously unoccupied area. Nobody has to pay to live on their own land - they have to pay to live on someone else’s land if they voluntarily move to it.

“Nightmare libertarian project turns Honduras into the murder capital of the world!” says Salon (Honduras’ murder rate has been consistently terrible, started its most recent increase in 2006, started going down in 2011, and is now around the same as it was in 1990; the libertarians control an area of land smaller than a golf course in a country of ten million people). New Republic quoting a Honduran journalist: “I’ve seen all sorts of horrific things in my time, but none as detrimental to the country as this.” (Hurricane Mitch hit Honduras in 1998, killing 7,000 people and leaving 1.5 million homeless; Próspera plans to build a nice city on unoccupied land and let people live in it if they want).

Meanwhile, every week the regular government of Honduras does worse things than anyone in a ZEDE has ever done to anybody, and nobody cares because they’re not libertarians so it doesn’t count.

Other people are playing up the ultra-nationalist side of things. The territorial integrity of Honduras is the most important thing possible! It would be better for everyone to die than to see even one inch of Honduras get governed by institutions that foreigners had a hand in designing! I have never understood why Japanese people will give their lives to keep some uninhabited ocean rocks from the clutches of China, or vice versa, but there seem to be a lot of Hondurans equally concerned about a 58-acre parcel of uninhabited land on Roatan. The new ZEDE law, which emphasizes that the territories remain within some of Honduras’ institutions, seem to have partly (but not completely) cooled some of these sentiments.

10.2.1. Can you steel-man the case against Próspera?

There are a few other arguments that I find more concerning.

First, although Próspera’s unlikely to expropriate land, nothing prevents them from buying land from its rightful owners. If those rightful owners are landlords, then their tenants could unexpectedly end up in Próspera. Próspera’s only allowed to do this in low-density areas, but much of Roatan is officially classified as low-density. Although Próspera intends to mostly buy unoccupied land, they won’t rule out a situation where eg they buy a mostly-unoccupied area with a groundskeeper who lives in a rented groundskeeper’s hut somewhere on the property, and then that groundskeeper might find themselves in Próspera unexpectedly.

This is - maybe not a giant human rights violation? Landlords can already kick tenants out of their land. And getting unexpectedly added to Próspera seems strictly less bad than getting kicked out, since the worst case scenario is you can always choose to leave. Also, if everything goes according to plan this should happen very rarely, maybe one or two groundskeepers per giant city. But accepting for the sake of argument that anything bad is much worse when libertarians do it, this is one of the possible bad things.

Second, people on the edges of Próspera will probably experience a lot of gentrification. I trust Próspera’s commitment not to annex Crawfish Rock. But they do plan to build a giant very rich city surrounding Crawfish Rock on all sides, and it would be surprising if that had no effect on Crawfish Rock itself. This is no different than what everyone on the outskirts of every city in the world has had to experience as those cities grow, but it’s another possible bad thing. At least if you’re a renter there. If you own property there, I guess you’re now super-rich.

Third, could Próspera become a tax haven? Rather, given that they have a tax rate of 10% in a country with a tax rate of about 25%, why wouldn’t it become a tax haven? I asked Trey, who said that Honduras is awful at collecting taxes, and rich Honduran tax evaders already have plenty of options without having to move to a charter city. Honduras has a 25% tax rate but doesn’t collect; Próspera plans to have a 10% tax rate and collect every cent.

Fourth, is Honduras really getting its money worth? Próspera has 10% taxes, and Honduras gets 12% of that. So they get 1% of economic activity in the ZEDE. But Próspera won’t have its own military, criminal justice system, prison system, etc - it will be parasitic on Honduras for a lot of this. Presumably the central government hopes that 1% of economic activity will pay for all this and then some. If they’re wrong, a lot of people are going to be really mad.

I’m pretty surprised Honduras didn’t hold out for a better deal. I don’t think this is Próspera’s fault. Próspera didn’t exist when the original ZEDE negotiations were going on. But they have a monopoly - no one else is offering a ZEDE-like product - and you’d think they could have gotten a better price from it.

10.3 And what’s the case for?

Thousands of Hondurans make the dangerous journey to the United States in search of freedom, safety, and a living wage. They’re tired of poverty and murder and corruption and think that a well-run polity with capitalist institutions can help them build a better life. I can’t blame them one whit. America is a better place to live than Honduras. This isn’t because Americans are smarter, or harder-working, or morally superior. It’s because Honduras has bad institutions.

But these people will probably or get turned away at the border, or languish in ICE detention camps, or die en route. Right now, we’re failing these people, not to mention the thousands more who wish they could make the same journey but are too scared to try. Próspera wants to give these people a better option by bringing American-style institutions to Honduras. They’re not going to displace any existing residents or include anyone who doesn’t want to be included. They just want to give people who have been ill-served by statism and nationalism a choice other than traveling three thousand miles and scrambling over barbed wire fences.

If you were a completely ordinary Honduran, making $1,300 a year, having a medium lifetime risk of being murdered, with the government occasionally taking your land and killing you if you complained - would you want the option of moving to Próspera? With its civil rights, property rights, strong security, good education, and higher salaries? I have these things right now in America and they’re great. I can’t imagine wanting these privileges for myself and also working to deny them to others. The people who like statism, ultra-nationalism, and the status quo have an entire world to play around in, and it’s turned out…well, you can see how it’s turned out. The Prósperans want 58 acres to try something different.

Also, remember status quo bias. If Próspera already existed, and somebody asked to take some of their land and create Honduras, would that be ethical? Absent a great answer to that question, it’s hard for me to worry about the reverse.

10.3.1. So the case is that it’ll be good for Hondurans?

That’s the medium-good-case scenario. In the best-case scenario, it could also be good for everyone else.

When China created the Shenzhen special economic zone, its success didn’t just enrich Shenzhen. It became the evidence that Chinese liberals used to enact reforms across the whole country, and Chinese GDP per capita dectupled over the next thirty years. And Vietnam saw China’s success and liberalized its own markets, and GDP there sextupled. And then Laos saw Vietnam’s success and liberalized its markets, and GDP there tripled. And before you know it, a billion and a half people were lifted out of poverty.

Próspera’s white paper mentions “expansion opportunities” in Guatemala, Dominican Republic, and Haiti. None of those countries allow ZEDEs now, and none of them seem interested in changing that. But if they watch Honduras get rich, maybe they’ll think again. There are six hundred million people in Latin America; who knows where they could be thirty years from now?

And maybe even the gringos can learn something. To my biased eye, Próspera’s institutions aren’t just better than Honduran institutions. They might well be better than the institutions of America, Europe, and the rest of the developed world. Some of their ideas - 3D property rights, modular construction, common law regulatory options, medical reciprocity laws - are genuinely innovative, the first in the world. They’re things that intellectuals have been discussing for decades, and then suddenly some progressive-minded people get a jurisdiction to try them out in and see if they work. I won’t call this historically unprecedented - for example, it happened in 1776 - but it’s a rare opportunity.

Never underestimate embarrassment as a driver of progress. When the US was dragging its feet on COVID vaccines, Israel vaccinated its population quickly and safely, and that embarrassed us enough to get the ball rolling. Or: the US is terrible at building infrastructure. We’re starting to discuss ways to fix this, but we wouldn’t have realized anything was wrong without stories about China constructing high-speed rail at lightning speed, or memories of our grandparents building Hoover Dam and the interstate highways.

If Próspera gets - I don’t know, let’s say a network of cheap VTOL air taxi drones - maybe we’ll find we can still feel shame. Maybe it’ll be embarrassing to have Honduras beat us to the future. Maybe we’ll start wondering if we can learn something.

10.4. What’s the case for being neither outraged or inspired but just kind of bored?

I can’t stress enough that right now, Próspera is 58 acres (the size of an average housing development), with three buildings on it, next to a golf course. It has big potential. But right now, it’s that.

Also, its potential is - maybe not as big as it could be? If all of Próspera’s Roatan land deals go through, it can grow to about a thousand acres. That’s 1.5 square miles. That’s 10% the size of Dubai, 5% the size of Manhattan, and less than 1% the size of Singapore. Even if it gets the same population density as Manhattan, that only means about 100,000 people. And it probably won’t get the same population density as Manhattan. Manhattan has sixteen skyscrapers over a thousand feet tall. The tallest building on any of the renders of Próspera I saw had eight stories. Realistically the Roatan site will be a medium-sized town. This isn’t to say they can’t build more hubs on the mainland, or even elsewhere on Roatan. But even a cool VTOL drone network isn’t going to change the way agglomeration effects work - their original site has limited ability to grow into a major city.

Also, Honduras is very poor and has many people who need help. But that poverty and those people mostly aren’t on Roatan. Roatan is a tropical vacation paradise, full of beautiful five-star resorts, five-star restaurants, and five-star tourist traps.

A resort near Próspera Roatan. And by “near”, I mean “you can see it from their roof”.

A resort near Próspera Roatan. And by “near”, I mean “you can see it from their roof”.

This isn’t to say there are no poor people on Roatan. There are. But those poor people mostly aren’t poor because they lack access to the amenities of modern civilization. They’re poor because the giant golf resort next door doesn’t pay much for their particular skills, or because they can’t / don’t want to work for a golf resort. Adding more development to Roatan has limited ability to fix those problems, and Próspera isn’t going to be playing on hard mode until they start expanding to the rest of the country.

10.5. What’s your opinion?

It’s hard for me to get too freaked out about corporate model cities - I grew up in one. The Irvine family of California ranchers founded the Irvine Company to develop their land, and in the 1970s they partnered with the UC system and local real estate developers to build a new city. The result - Irvine, California - is constantly showing up in various Best City lists - #5 best public schools in America, #1 fiscally strongest city, #10 best place to raise a family, #8 healthiest, #3 greenest, #1 safest, etc, etc, etc. Also, Irvine Company head honcho Donald Bren made $17 billion and is now the 32nd richest man in America. I may not have extracted quite as much value from the experiment as Mr. Bren did, but I got a very good childhood out of it and I feel suitably grateful.

A typical Irvine commercial district, giving off heavy planned-city vibes.

A typical Irvine commercial district, giving off heavy planned-city vibes.

So while I understand that other people might find it shocking or crazy for a corporation to buy up some land, sketch a street plan, and try to make billions of dollars by creating as nice a city as possible, well - to me it kind of reminds me of home. I promise it’s not that weird when you’re living in it.

Próspera is a lot more ambitious than Irvine - not just planned streets and utility grids, but planned government and law code. It doesn’t just want to be the #X Nicest City, it wants to declare war on global poverty and win.

Maybe the extra ambition will ruin the magic formula and it won’t work out. I have no idea. But you miss a hundred percent of the moonshots you don’t take. I like the way Próspera thinks, and I look forward to seeing what happens.

11. Where can I learn more?

Próspera’s website is at https://prospera.hn/.

Their code of laws (warning: 3552 pages!) is online at http://pac.hn/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Prospera-Legal-Code-TOC-v11.10-Compressed-Protected.pdf

There are some anti-Prospera articles at https://contracorriente.red/en/2020/09/27/a-micronation-for-sale-in-roatan/ and (especially) https://bakerstreetherald.com/

There’s an unofficial Próspera subreddit at reddit.com/r/Prospera/ ; Trey is frequently around to answer questions.

Erick A. Brimen @erickbrimen

Erick A. Brimen @erickbrimen