Response To Alexandros Contra Me On Ivermectin

I.

In November 2021, I posted Ivermectin: Much More Than You Wanted To Know, where I tried to wade through the controversy on potential-COVID-drug ivermectin. Most studies of ivermectin to that point had found significant positive effects, sometimes very strong effects, but a few very big and well-regarded studies were negative, and the consensus of top academics and doctors was that it didn’t work. I wanted to figure out what was going on.

After looking at twenty-nine studies on a pro-ivermectin website’s list, I concluded that a few were fraudulent, many others seemed badly done, but there were still many strong studies that seemed to find that ivermectin worked. There were also many other strong studies that seemed to find that it didn’t. My usual heuristic is that when studies contradict, I trust bigger studies, more professionally done studies, and __(as a tiebreaker) negative studies - so I leaned towards the studies finding no effect. Still, it was strange that so many got such impressive results.

I thought the most plausible explanation for the discrepancy was Dr. Avi Bitterman’s hypothesis (now written up here) that ivermectin worked for its official indication of treating parasitic worms. COVID is frequently treated with steroids, steroids prevent the immune system from fighting a common parasitic worm called Strongyloides , and sometimes people getting treated for COVID died of Strongyloides hyperinfection. Ivermectin could prevent these deaths, which would mean fewer deaths in the treatment group than the control group, which would look like ivermectin preventing deaths from COVID in high-parasite-load areas (like the tropics) but not low-parasite-load areas (like temperate zones). This explained some of the mortality results, with the other endpoints likely being because of publication bias.

Alexandros Marinos is an entrepreneur, long-time ACX reader, and tireless participant in online ivermectin arguments. He put a very impressive amount of work into rebutting my post in a 21 part argument at his Substack, which he finished last October (if you don’t want to read all 21 parts, you can find a summary here). I promised to respond to him within a few months of him finishing, so that’s what I’m doing now.

I’ll be honest - I also didn’t want to read a 21 part argument. I would say I have read about half of his posts, and am mostly responding to the summary, going into individual posts only when I find we have a strong and real disagreement that requires further clarification. I also have had a bad time trying to discuss this with Alexandros (not necessarily his fault, I can be sensitive about these kinds of things) and am writing this out of obligation to honor and respond to someone who has put in a lot of work responding to me. It is not going to be as comprehensive and well-thought out as Alexandros probably deserves.

I’ll go through each subpart of his argument, as laid out in the summary post.

II. Individual Studies

Alexandros is completely right about one of these studies, partly right about a few others, and I still disagree with him on several more. On the one where I was wrong, I was egregiously wrong, and I apologize to the study authors and to you.

On the original post, I went through a list of 29 studies, trying to decide whether or not I trusted them. I dismissed 13 studies as untrustworthy (which didn’t necessarily mean fraudulent, just that I wasn’t sure they had good methodology). Then I dismissed 5 more studies that epidemiologist Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz didn’t like (even though I didn’t have strong objections to them myself), just to get a list of studies everyone agreed seemed pretty good. This part is about my study-keeping decisions. It won’t have a very big impact on the final result, since both Alexandros and I agreed that regardless of which study-dismissing criteria you use the final list supports ivermectin efficacy. But I still tried to get this right and mostly didn’t.

Alexandros critiques many of my study interpretations, but includes four in his summary. I’ll go over those four in detail, and make less detailed comments on the rest.

Biber et al (Alexandros 100% right)

The study I am most embarrassed about here is Biber et al, an Israeli study which found that COVID patients who received ivermectin had lower viral load. In the original post, I wrote:

This is an RCT from Israel. 47 patients got ivermectin and 42 placebo. Primary endpoint was viral load on day 6. I am having trouble finding out what happened with this; as far as I can tell it was a negative result and they buried it in favor of more interesting things. In a “multivariable logistic regression model, the adjusted odds ratio of negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR negative test” favored ivermectin over placebo (p = 0.03 for day 6, p = 0.01 for day 8), but this seems like the kind of thing you do when your primary outcome is boring and you’re angry.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz is not a fan. He notes that the study excluded people with high viral load, but the preregistration didn’t say they would do that. Looking more closely, he finds they did that because, if you included these people, the study got no positive results. So probably they did the study, found no positive results, re-ran it with various subsets of patients until they did get a positive result, and then claimed to have “excluded” patients who weren’t in the subset that worked.

I’m going to toss this one.

You can find Alexandros’ full critique here. His main concerns are:

-

I claimed that the primary outcome results were hidden, probably because they were negative. In fact, they were positive, and very clearly listed exactly where they should be in the abstract and results section.

-

That makes my dismissing their secondary outcomes as “the kind of thing you do when your primary outcome is boring and you’re angry” incorrect and offensive. The correct thought process is that their primary outcome was positive, and their secondary outcome was also positive, which they correctly mention.

-

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz’s objected to the researchers changing the (previously preregistered) procedure partway through. But the researchers had good reasons for doing that, they got the IRB’s permission, and they couldn’t have been cherry-picking, because they hadn’t seen results yet and didn’t know whether this would make ivermectin look more vs. less effective.

-

Gideon (correctly) phrased this as a non-sinister albeit potentially weird misstep by the study authors, but in trying to summarize Gideon, I (incorrectly) phrased it as a sinister attempt to inflate results.

After looking into it, I think Alexandros is completely right and I was completely wrong. Although I sometimes get details wrong, this one was especially disappointing because I incorrectly tarnished the reputation of Biber et al and implicitly accused them of bad scientific practices, which they were not doing. I believed I was relaying an accusation by Gideon (who I trust), but I was wrong and he was not accusing them of that. I apologize to Biber et al, my readers, and everyone else involved in this.

My only reservation is that I don’t want to say too strongly that Gideon’s critique is wrong: I haven’t looked through the study documents enough to say with certainty that Alexandros’ reanalysis of the protocol issues is correct (though the superficial check I’ve done looks that way). But my mistakes are completely separate from anything Gideon did and definitely real and egregious.

Cadegiani et al (Alexandros 50% right)

Flavio Cadegiani did several studies on ivermectin in Brazil; I edited this section in response to criticism by Marinos and others, but the earliest version I can find on archive.is (I can’t guarantee it was the first I wrote) said:

A crazy person decided to put his patients on every weird medication he could think of, and 585 subjects ended up on a combination of ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and nitazoxanide, with dutasteride and spironolactone “optionally offered” and vitamin D, vitamin C, zinc, apixaban, rivaraxoban, enoxaparin, and glucocorticoids “added according to clinical judgment”. There was no control group, but the author helpfully designated some random patients in his area as a sort-of-control, and then synthetically generated a second control group based on “a precise estimative based on a thorough and structured review of articles indexed in PubMed and MEDLINE and statements by official government agencies and specific medical societies”.

Patients in the experimental group were twice as likely to recover (p < 0.0001), had negative PCR after 14 vs. 21 days, and had 0 vs. 27 hospitalizations.

Speaking of low p-values, some people did fraud-detection tests on another of Cadegiani’s COVID-19 studies and got values like p < 8.24E-11 in favor of it being fraudulent. Also in Cadegiani news: he apparently has the record for completing one of the fastest PhDs in Brazilian history (7 months), he was involved in a weird scandal where the Brazilian government tried to create a COVID recommendation app but it just recommended ivermectin to everybody regardless of what input it got, and he describes himself as:

…the only author of the sole book in Overtraining Syndrome, the prevailing sport-related disease among amateur and professional athletes. He is also responsible for approximately 70% of the articles published in the field in the world in the last 05 years, and reviewer for more than 90% of the manuscripts in the field.

And, uh, he’s also studied whether ultra-high-dose antiandrogens treated COVID, and found that they did, cutting mortality by 92% . Which sounds great, except that it looks like most of this is that the control group had a shockingly high mortality rate, much higher than makes sense even in the context of severe COVID. I think the charitable explanation here is that he made this data up too. But the Brazilian Parliament seems to be going with an uncharitable explanation, seeing as they have recommended that Cadegiani be charged with crimes against humanity.

Anyway, let’s not base anything important on the results of this study.

You can find Alexandros’ full critique here, but again I’ll try to summarize it as best I can.

-

Alexandros is unhappy with my portrayal of Cadegiani’s background. I cite details that make him look strange and maybe fake, but there are other details that make him seem more impressive, like that he won gold medals at a Brazilian Scientific Olympiad.

-

I mention Cadegiani’s “involvement” in a scandal where the Brailizan government created a COVID recommendation app that recommended ivermectin to everyone. Marinos points out that it did alter its recommendations based on the patient (eg what other drugs it recommended, what dose of ivermectin to use), and although it had some problems it was overall an okay app whose only “crime” was operating on the assumption that ivermectin was a great COVID drug.

-

More to the point, although the app cited Cadegiani’s research, he was not involved in creating it, and in fact criticized it (yes, there is some tension between Alexandros defending the app and defending Cadegiani for criticizing it; he argues that he has no position on the app’s quality but does not think it has been shown to be a “scandal”)

-

The Brazilian Parliament did recommend that Cadegiani be charged with crimes against humanity for his trial, but this was for not giving the drugs to the control group, not for excess mortality in the control group (is this nonsensical? Doesn’t this mean that the medical establishment wants to blame Cadegiani both for giving drugs that don’t work, and for not giving them to enough people? Alexandros argues that yes, the establishment really is that dumb).

-

Alexandros doesn’t dispute that one of Cadegiani’s trial had some impossible-seeming statistics, but says we shouldn’t jump to allegations of fraud, shouldn’t let this unduly influence our opinion of Cadegiani’s other trials, and also accuses Kyle Sheldrick, the person who discovered the discrepancy, of doing other bad things.

My responses:

Alexandros’ Point 1 is fair-ish. Since this person appears to be commiting pretty substantial fraud and doing some strange things, I thought it was useful to highlight the ways in which he is weird and suspicious, rather than the ways he is prestigious and impressive. But probably I went too far in this.

His Point 2/3 is completely fair, and I’m sorry for getting this wrong. I may have unthinkingly copied it from forbetterscience.com, which made this mistake before me, or I might have just failed at reading comprehension on this translated Portugese-language article I linked. In either case, I apologize to Cadegiani. This is already on my Mistakes page as of June 2022 when Alexandros wrote his original article.

His Point 4 is correct, although based on information that came out after I wrote my article. All that was available in English when I wrote was that the Brazilian government was considering accusing Cadegiani of crimes against humanity. I think I did an okay job noting that I was guessing at their reasoning (rather than reporting a known fact), and as written I did make clear that I thought he was innocent of the specific charge. Still, I appreciate the clarification.

His Point 5 is - I do feel like Alexandros is having a sort of missing mood on the fact that one of Cadegiani’s big pro-ivermectin studies contains impossible data. While this is not proof of fraud or incompetence, it is some Bayesian evidence for both. And while fraud or incompetence in one of your studies supporting ivermectin is not proof that your other studies supporting ivermectin are also fraudulent/incompetent, it is, again, Bayesian evidence.

Alexandros makes a big deal of there being four corrections in the BMJ article attacking Cadegiani, as if now the BMJ has admitted they were wrong all along, whereas these were mostly on unrelated details and the BMJ definitely did not correct the quotes about how his study was “an ethical cesspool of violations” or how “in the entire history of the National Health Council, there has never been such disrespect for ethical standards and research participants in the country”1. I feel like if his Science Olympiad medals are an important part of the story, these kinds of things are an important part too.

Still, several of Alexandros’ points were entirely correct, and I appreciate the corrections.

Babalola et al (still disagree with Alexandros)

OE Babalola (I incorrectly wrote this name as “Babaloba” in the original) did a Nigerian study which found that ivermectin decreased the amount of time it took before people tested negative for COVID. I described this study as:

This was a Nigerian RCT comparing 21 patients on low-dose ivermectin, 21 patients on high-dose ivermectin, and 20 patients on a combination of lopinavir and ritonavir, a combination antiviral which later studies found not to work for COVID and which might as well be considered a placebo. Primary outcome, as usual, was days until a negative PCR test. High dose ivermectin was 4.65 days, low dose was 6 days, control was 9.15, p = 0.035.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, part of the team that detects fraud in ivermectin papers, is not a fan of this one. He doesn’t say there what means, but elsewhere he tweets [this figure highlighting how the study has “Numerous impossible numbers”]

I think his point is that if you have 21 people, it’s impossible to have 50% of them have headache, because that would be 10.5. If 10 people have a headache, it would be 47.6%; if 11, 52%. So something is clearly wrong here. Seems like a relatively minor mistake, and Meyerowitz-Katz stops short of calling fraud, but it’s not a good look.

I’m going to be slightly uncomfortable with this study without rejecting it entirely, and move on.

Alexandros calls this The Sullying Of Babalola Et Al, and says I “followed Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz off a cliff” by unfairly “lambasting” the innocent Babalola. I “[made] a mountain out of a molehill”.

Alexandros quotes a commenter who found that the most likely explanation for the “impossible numbers” in Babaloba was missing data, and notes that usually-anti-ivermectin researcher Kyle Sheldrick had evaluated the raw data and found no fraud. Alexandros concludes:

As far as I can tell, Scott discarded a good study here, and besmirched the reputation of the researchers by amplifying flimsy allegations that were known to be off-base at the time that the article was written.

I don’t think I did anything especially wrong here. There was a chart that didn’t make sense. It turned out not to make sense because some data was missing. I said “[this] seems like a relatively minor mistake, and Meyerowitz-Katz stops short of calling fraud, but it’s not a good look. I’m going to be slightly uncomfortable with this study without rejecting it entirely, and move on.”

I was right that it was a minor mistake, I was right that it wasn’t fraud, and I was right not to reject the study. I didn’t have the exact explanation (missing data), so I did not mention it, but I think I made the correct guess about the sort of explanation it was. I don’t understand why Alexandros acts like I said the study wasn’t worth keeping, or that there was no innocent explanation, or that I was accusing the researchers of fraud, when in fact I said the opposite of all those things, pretty explicitly.2

Carvallo et al (Alexandros 25% right)

This was an Argentine study. I described it as:

This one has all the disadvantages of Espitia-Hernandez, plus it’s completely unreadable. It’s hard to figure out how many patients there were, whether it was an RCT or not, etc. It looks like maybe there were 42 experimentals and 14 controls, and the controls were about 10x more likely to die than the experimentals. Seems pretty bad.

On the other hand, another Carvallo paper was retracted because of fraud: apparently the hospital where the study supposedly took place said it never happened there. I can’t tell if this is a different version of that study, a pilot study for that study, or a different study by the same guy. Anyway, it’s too confusing to interpret, shows implausible results, and is by a known fraudster, so I feel okay about ignoring this one.

Alexandros responds here. Attempting to summarize his points:

-

He agrees this study is extremely confusing.

-

The other Carvallo paper was accused of fraud, but not actually retracted.

-

The fraud accusation (primarily described in this Buzzfeed article, which Alexandros believes is unfair) was for a study done in four hospitals. One of the hospitals denied knowing anything about it or authorizing it. But the main hospital said they did know about it and authorize it, it (according to Carvallo) it is considered okay in Argentina to let hospital staff enroll in trials without telling the hospital.3

-

The study does have a lot of data collection issues and Alexandros agrees we shouldn’t take it seriously, he just disagrees with calling it fraud.

This is a good place to note that I very poor memory of what I was thinking two years ago, and am having to reconstruct my arguments as I go. Still, reading the BuzzFeed article, I notice things like:

-

Different sources about the study contradict each other (or gave seemingly impossible numbers for) when the study happened, how many patients were involved, and how old they were.

-

Dr. Carvallo said that another researcher, Dr. Lombardo, had reviewed these data. But Dr. Lombardo denied ever having been involved.

-

Not only did a hospital claim that they weren’t formally involved in the study, but the infectious disease doctor at the hospital said none of his colleagues that he knew of had participated, and he had never seen any ads inviting people at that hospital to participate. After this, all references to that hospital in the paper were changed to “other peripheral medical center”. Carvallo said he changed it only because the hospital wanted to do a trial of some other drug; the infectious disease doctor from the hospital said that was “an absolute lie”.

-

Carvallo refused to release the data from the study to anyone who asked for it. When one of his coauthors asked Carvallo for the data, Carvallo claimed to have given it to him, but actually only gave him “summaries of the results and a written narrative of how the study was carried out”. His collaborator was so disgusted that he withdrew his coauthorship and asked for his name to be removed from the article.

-

Carvallo said that zero people in the treatment group of his study got COVID, compared to 58% of people in the control group. This is a pretty implausibly big effect, even by the standards of other pro-ivermectin studies, although I don’t know if anyone else tried the exact same preventative protocol as Carvallo.

I think this is a more nuanced story than Alexandros’ version where Buzzfeed just doesn’t know that sometimes studies happen at more than one hospital.

Is fraud the best explanation? I think Alexandros thinks of Carvallo as just not keeping very good records, so he doesn’t have raw data, and probably mixed up his numbers a few times or gave false numbers, and didn’t have anything to send his collaborators when they asked. I think this is maybe possible, although it seems suspicious that he falsely said Dr. Lombardo was involved, falsely claimed the hospital involved was doing a different trial, and got very implausible results. I can imagine weird chains of events that would cause all of these things through honest misunderstandings. But they don’t seem like the best explanation.

After discussing this with Alexandros, he objects to my use of the term “known fraudster”. Perhaps I should have said “highly credibly suspected fraudster” instead, although in a Bayesian sense nothing can ever be 100% and at some point plausibility shades imperceptibly into knowledge. Still, I feel like my description here was more accurate than Alexandros’, which just mentions the hospital approval issue and says nothing about any of the rest of this in a thousand word subsection about this study in particular.

I did err in saying the Carvallo paper was retracted. According to the article:

After BuzzFeed News raised questions about how the study’s data was collected and analyzed, a representative from the Journal of Biomedical Research and Clinical Investigation, which published the results, said late Monday, “We will remove the paper temporarily.” A link was removed from the table of contents — but was reinstated by Thursday. The journal’s explanation, provided after this story was published, was that the author “informed us that he has already provided the evidence of his study to the media.”

I apologize for the error.

Elalfy et al (still disagree with Alexandros)

I described this as:

As best I can tell, this is some kind of Egyptian trial. It might or might not be an RCT; it says stuff like “Patients were self-allocated to the treatment groups; the first 3 days of the week for the intervention arm while the other 3 days for symptomatic treatment”. Were they self-allocated in the sense that they got to choose? Doesn’t that mean it’s not random? Aren’t there seven days in a week? These are among the many questions that Elalfy et al do not answer for us.

The control group (which they seem to think can also be called “the white group”) took zinc, paracetamol, and maybe azithromycin. The intervention group took zinc, nitazoxanide, ribavirin, and ivermectin. There were very large demographic differences between the groups of the sort which make the study unusable […]

There is no primary outcome assigned, but viral clearance rates on day seven were 58% in the yellow group compared to 0% in the white group, which I guess is a strong positive result.

This table looks very impressive, in terms of the experimental group doing better than the control, except that they don’t specify whether it was before the trial or after it, and at least one online commentator thinks it might have been before, in which case it’s only impressive how thoroughly they failed to randomize their groups.

Overall I don’t feel bad throwing this study out. I hope it one day succeeds in returning to its home planet.

In the summary post, Alexandros’ entire criticism of my coverage of this trial, one of the seven trials he focuses on as most unfairly covered and uses as the lynchpin of his argument that I am morally culpable for disastrously bad reporting, is:

[Elalfy et al] are accused of incompetence for failing to randomize their groups multiple times in Scott’s piece. The paper writes in six separate places that it is not reporting on a randomized trial, amongst them on a diagram that Scott included in his own essay. Hard to imagine how else they could have made it clear.

In his full post on this, he goes line by line to point out all the places they say they are non-randomized, pausing to snark about how dumb I am for not noticing each time4. But he never addresses the actual source of my confusion, which is the part of the paper where it says that:

Patients were self-allocated to the treatment groups; the first 3 days of the week for the intervention arm while the other 3 days for symptomatic treatment.

If this was done as described, it should be an (almost) random trial; patients who come in on Wednesdays shouldn’t systematically differ from patients who come in on Thursdays5. But in fact, it looks (assuming I am understanding a very ambiguous table correctly) like there are very large pre-existing differences between the groups, sufficient to explain the entire result. If they in fact followed their days-of-the-week protocol, and it was random as expected, then I’m misunderstanding the table seeming to show very large differences, and they have indeed found evidence for ivermectin’s efficacy. If they didn’t follow their day-of-the-week protocol and it’s non-random, then maybe I’m understanding the table correctly and their groups had large differences to begin with and the fact that they had large differences at the end of the trial doesn’t demonstrate anything about ivermectin. This is all I was trying to say in the post, and instead of having any opinion on it Alexandros just makes fun of me for saying it.

I think our actual crux is that Alexandros thinks a table of big differences between the groups has to be post-treatment (based on how big the differences are), whereas I’m not sure (because it’s unclear in the study, and also because the authors describe what could be a randomization method but also go on and on about how nonrandom they are). This is why I thought it mattered how random it was! Maybe instead of mocking me for this, you can admit it’s an important and relevant question!

Ghauri et al (still disagree with Alexandros)

I describe this as:

Pakistan, 95 patients. Nonrandom; the study compared patients who happened to be given ivermectin (along with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin) vs. patients who were just given the latter two drugs. There’s some evidence this produced systematic differences between the two groups - for example, patients in the control group were 3x more likely to have had diarrhea (this makes sense; diarrhea is a potential ivermectin side effect, so you probably wouldn’t give it to people already struggling with this problem). Also, the control group was twice as likely to be getting corticosteroids, maybe a marker for illness severity. Primary outcome was what percent of both groups had a fever: on day 7 it was 21% of ivermectin patients vs. 65% of controls, p < 0.001. No other outcomes were reported.

I don’t hate this study, but I think the nonrandom assignment (and observed systematic differences) is a pretty fatal flaw.

Alexandros notes that these are three differences between experimental/control groups, out of 33 listed characteristics that could have been different. There is approximately a 23% chance (he calculates) that you could get these differences by chance. He accuses me of failing to do a formal Carlisle test - the usual test you would use to determine whether weird differences between randomized groups are because of fraud - instead eyeballing it and getting it wrong.

Here I do want to defend myself: I am not accusing Ghauri et al of fraud. In fact, this would be nonsensical: they admit they are assigning patients nonrandomly. Carlisle tests are usually done to show that something about group assignment is impossible (and therefore fraudulent) in a fair random assignment. But these people aren’t claiming to have done a fair random assignment, so I’m not sure what a Carlisle test would prove.

My argument is more like: this is nonrandom, therefore we should expect it to be unfair. It is unnecessary, but helpful, to note an actual apparent unfairness - there’s some evidence they gave the ivermectin to less severe patients (as measured by corticosteroid use). Therefore, we can’t necessarily trust this to be a fair trial (which it was never really claiming to be).

In the end I kept Ghauri as an okay study, although GMK didn’t so it ended out trashed in the final analysis anyway. I think my thinking was that I never claimed to be only looking at RCTs, so this non-RCT whose between-group-differences confirmed that it was indeed a non-RCT with all the risk of bias that entails, didn’t necessarily need to be ruled out. Still, I don’t think I was wrong to mention this possibility, and I think Alexandros was wrong to suggest that I needed to do extra tests for this to be fair.

Borody et al (still disagree with Alexandros)

I described this as:

Our last paper!

…is it a paper? I can’t find it published anywhere. It mostly seems to be on news sites. Doesn’t look peer-reviewed. And it starts with “Note that views expressed in this opinion article are the writer’s personal views”. Whatever. 600 Australians were treated with ivermectin, doxycycline, and zinc. The article compares this to an “equivalent control group” made of “contemporary infected subjects in Australia obtained from published Covid Tracking Data”; this is not how you control group, @#!% you.

Then it gets excited about the fact that most patients had better symptoms at the end of the ten-day study period than the beginning (untreated COVID resolves in about ten days). Why are these people wasting my time with this? Let’s move on.

Alexandros lists his full concerns here. My summary:

-

Scott is being incredibly disrespectful to the authors, who are in fact a legendary gastroenterologist who invented life-saving h. pylori therapy and a brilliant immunologist who invented a well-regarded bronchitis vaccine (in particular, in describing their control group, I said “this is not how you control group, @#!% you”.

-

“Synthetic control groups” - ie comparing people in a trial to some previously-known understanding of how a disease progresses - are a standard practice, and basically fine.

Borody et al indeed have had amazing careers with many things they can be proud of. But I continue to believe that this paper is not among them.

Synthetic control groups are more common in social sciences, but have occasionally been used in pharmacology when it would be unethical or extremely difficult to use a real control group. The most common use case is rare cancers, where it takes years to get enough patients to test a drug and it also seems kind of unethical to delay. Another good thing about rare cancers is that they’re pretty discrete; you don’t have to worry about things like “well, 90% of leukemias never make it to a doctor anyway, so maybe we’re only seeing the serious leukemias” or “these guys counted the leukemias that get dealt with by the local doctors’ office, but those other guys counted the leukemias that have to go to the hospital”.

More important, studies with synthetic control groups usually go above and beyond to justify why their synthetic control group should be a fair comparison to the treatment group. Here’s an example, from a paper about a rare leukemia. They start by getting a synthetic control group from a previous randomized controlled trial of leukemia drugs (not the general population!) Then they throw out more than half their patients for not being a good match for the selection criteria of the current study. Then they investigate whether there are significant differences on five important demographic factors, and find a few. Then they re-weight the patients in the historical comaprator study to adjust out the differences between the previous population and the current population. Then they do some analyses to check if they re-weighted everything correctly. Then they apologize profusely for having to use this vastly inferior methodology at all:

In special cases when a disease is rare, prognosis is very poor, and there are limited therapeutic options available, single-arm clinical trials may be used as evidence for accelerated drug approvals. Comprehensive evaluation of historical comparator or reference data can provide an additional approach for putting the efficacy of a new therapy into perspective.11, 12 In this study, we applied different statistical methods and sensitivity analyses to evaluate the clinical efficacy of blinatumomab against historical data.

Concerns often raised regarding the use of historical comparator data are the influence of potential biases related to selection, misclassification and confounding.12 The requirement of rigorous eligibility criteria in the blinatumomab clinical study—such as Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status of two or lower and absence of abnormal lab values during screening—may increase the chance of better outcomes in the clinical study than the historical data. While it may be possible to use unadjusted historical data when patient populations are sufficiently similar,27 the disproportionate number of advanced-stage patients in the blinatumomab trial required methods applied to individual-level data to minimize bias. Selection bias was minimized by use of stringent inclusion criteria into the historical data set and by weighting or adjusting for known prognostic factors. In addition, the historical data set represented adult R/R patients who received standard of care (excluding palliative care patients where possible), without any restrictions to any patient subgroups. Residual confounding may still remain and be difficult to control for, particularly in data sets where differences in important prognostic factors are unknown or not measured in one data set. In this study, nearly all known important prognostic factors were adjusted for in the weighted or propensity score analyses. Missing data on key covariates lead to exclusion of some records from the analyses (Figure 1), which may theoretically bias the overall results. However, our examination of records with missing covariates did not identify significant differences by patient demographic characteristics compared with patients who had complete data (data not shown). Misclassification bias was limited by harmonization of patient-level data in the pooled analysis, which employed common data definitions for disease classification and outcomes characterization.

Compare this to how the Borody study discusses its synthetic control group:

The control data was from contemporary infected subjects in Australia obtained from published Covid Tracking Data.

I hesitate to say “they didn’t even say which tracking data”, because in the past I’ve said things like that and just missed it. But I can’t find them saying which tracking data.

In Borody et al’s synthetic control group, 70/600 (11.5%) patients required hospitalization. But the US hospitalization rate appears to be about 1% for unvaccinated individuals. So Borody’s synthetic control group got 10x the expected hospitalization rate. This seems very relevant to this study finding that ivermectin decreases hospitalization by 90%! I’m not claiming this is fraudulent, or impossible, or means the study couldn’t have been good. And Borody claim to have used an “equivalent” control group, so maybe there was some adjustment done for this. But this is why we usually use more than one word to describe our control groups! Or use real control groups that don’t ruin your study if you do a finicky adjustment slightly wrong!

I feel like these are the kinds of questions Alexandros needs to be asking, instead of just giving a link to a Stat News article about how sometimes synthetic control groups are okay. Also other questions, like “how come this found a 90% decrease in hospitalization and mortality, but lots of other studies found smaller decreases, and the biggest and best studies found none at all?” I know Alexandros’ answers are to find lots of flaws with the biggest and best studies, but these flaws wouldn’t be enough to cover up a 90% cure rate. And if you’re in the business of calling out flaws in studies I genuinely think having your control group be “we used some group of people somewhere in Australia, they had 10x the normal hospitalization rate, we won’t tell you anything else” would be the sort of flaw you would call out!

Thomas Borody is a genuinely brilliant gastroenterologist and I am very grateful for his life-saving discoveries. But Elon Musk is a genuinely brilliant engineer and I am very grateful for his low-cost reusable rockets - and this doesn’t mean he never does crazy inexplicable things. Maybe Borody and his collaborators have a point from this study, but I don’t feel like it makes sense as written. If they ever explain what they were doing in more detail and it’s some sort of amazing 4D-chess move that makes total sense, I will apologize to them. Otherwise, stick to inventing amazing life-saving digestive therapies.

In response to this section, Alexandros stresses that he is not necessarily saying Borody et al is incorrect or challenging my decision to leave it out. He writes:

I will repeat that my strong objection, is that you wrote “ this is not how you control group, @#!% you”. I therefore pointed to stat news to support my case that, yes, this can indeed be how you control group. That’s all. In the article I even noted that this aversion towards disrespect to elders may even be a cultural difference between us.

To be clear, if I were making a case for ivermectin, I would not be relying on this study as my starting point.

III. Hokey Meta-Analysis

Alexandros points out that I used the wrong statistical test when analyzing the overall picture gleaned from this studies. He’s right. The right statistical test would make ivermectin look stronger, without changing the sign of the conclusion.

After getting a core group of potentially trustworthy studies, I tried to see whether ivermectin still had a statistically significant positive effect in them. I tried to be honest that I didn’t really know how to do formal meta-analyses:

Probably I’m forgetting some reason I can’t just do simple summary statistics to this, but whatever. It is p = 0.15 , not significant . . . What happens if I unprincipledly pick whatever I think the most reasonable outcome to use from each study is? . . . Now it’s p = 0.04 , seemingly significant

I in fact could not do simple summary statistics to this. Alexandros describes the test I should have used, a DerSimonian-Laird test, and applies it to the same data. Now the numbers are p = 0.03 and p < 0.0001. I accept that I was wrong, he is right, and this is more accurate.

My original conclusion to this section is that although you couldn’t be absolutely sure from the numbers, eyeballing things it definitely looked like ivermectin had an effect. I then went on to try to explain that effect. With Marinos’ corrections, you can be sure from the numbers, but the rest of the post - an attempt to explain the effect - still stands.

IV. Worms

Alexandros brings up issues with the Strongyloideshypothesis; Dr. Bitterman graciously responds. I find the issues real enough to lower my credence in the idea, but not to completely rule it out. Even if it is true, I probably overestimated how important it was.

My original explanation for the effect was Dr. Avi Bitterman’s theory of Strongyloides hyperinfection.

Many people in certain tropical regions are infected with the parasitic worm Strongyloides. Usually a person’s immune system keeps this worm under control, and the parasites cause only limited problems. But under certain situations - especially when people take immune-suppressing corticosteroids - the immune system fails, the worms multiply, and the patient can potentially die of sudden worm overgrowth (“hyperinfection”). Corticosteroids are a common COVID treatment. So plausibly some people in tropical areas fighting COVID are at risk of dying from worm hyperinfection. Ivermectin was originally an anti-parasitic-worm medication before being repurposed to fight COVID, and everyone agrees it is very good at this. So if many people in COVID trials are dying of worm infections, then ivermectin could help them. This would look like ivermectin reducing mortality in COVID trials, and make people wrongly conclude that ivermectin treats COVID.

Alexandros responds to this theory here, again I’ll try to summarize:

-

The original Bitterman paper concludes that ivermectin trials show stronger results in high-_Strongyloides_ -prevalence regions. But it mixes prevalence data from two different papers with different methodologies. Correcting for this, the findings no longer clear a formal bar for statistical significance, and don’t really look significant either.

-

Strongyloides hyperinfection usually doesn’t kill patients for several weeks. Most of the COVID trials weren’t observing steroid patients for long enough that hyperinfection was likely to be a concern.

-

Strongyloides hyperinfection isn’t subtle: you can sometimes see worm-shaped tracks along the patient’s skin. Not only would you expect the doctors in the studies to have noticed this and mentioned it, but you would expect a large published literature on cases of Strongyloides hyperinfection during COVID treatment. There is a small literature on this, but not enough to make it look like a common, trial-disrupting event.

-

In some cases, we can look at the data from the original trials and check things like whether the patients who died were on steroids, or took a long time to die, or had hyperinfection-like symptoms - and in a lot of cases they weren’t and didn’t.

-

The control groups in high-worm-prevalence-area studies had no more deaths than in low-worm-prevalence-area studies. If the worms were killing people in the control groups (who ivermectin was then saving in the treatment groups) you would expect more deaths.

You can find arguments for all these points at the link.

(One additional thing Alexandros does that I really like: he compares the Strongyloides hypothesis - as an attempt to explain why these studies keep getting such different results - to other hypotheses. For example, studies in Latin America get negative results more often than others. This really feels like confronting the real question. He finds that Latin American studies do find lower efficacy for ivermectin than the other mostly Asian studies, and hypothesizes that this is because ivermectin is very popular in Latin America, the “control” group illicitly takes it without telling the researchers, and so these studies are inadvertantly comparing two ivermectin groups. This is another clever and elegant theory. Unfortunately, the recent spate of negative American studies sink it6. Still, I agree there is a strong geographic element here; worms are one possible explanation, but there are others - including the scientific culture in different countries. I appreciate Alexandros highlighting how much this is true.)

I asked Dr. Bitterman for his thoughts. He reiterates that although steroids are one major cause of Strongyloides hyperinfection, another is eosinopenia, a decrease in the immune cells that fight parasites. COVID can cause eosinopenia directly, so just because a COVID patient didn’t get steroids, or was only on steroids for a short period, doesn’t prove that the patient couldn’t have had hyperinfection.

On the mixing of different sources to get Strongyloides prevalence data, he said:

As mentioned in the paper, when available we attempted to granulate by regional prevalence. This was often not possible because robust data did not available for a given country. Brazil is a large country (and multiple different studies in our analysis were in Brazil) with variability and Paula was a robust study. We decided to attempt to granulate instead of stacking the Brazil countries with the same prevalence even though they are in very different regions. His re-analysis is a crude one, and he often switches between using that analysis and the ecological model study. At the time of out paper’s publication, the ecological model was not available. I offered to re-do the whole analysis with that study’s raw data with a mutually agreed upon methodology, which we have not fully ironed down yet.

On the long delay before hyperinfection kills:

I don’t think it happens in 1 or 2 weeks. But 3-4 weeks (within almost all study durations) is certainly not unheard of (again, without being treated). Even 1/3rd of the [untreated animals in a marmoset study Alexandros cites] died within the range of the study durations.”

On the more general argument:

I have a higher credence of the effect modifier than he does. Perhaps the main thing I don’t think he fully appreciates is just how few deaths need to be explained by this in order to substantially shift the RR. Even if this is the case for just a handful of control group deaths, the RR change is not trivial simply because of how low events the entire supposed benefit was in the first place. Furthermore, the new trials (ACTIV-6 400, ACTIV-6 600, COVID-OUT), while they all have very low mortality rates, all tip the needle in favor of the hypothesis. As expected, in the USA where the prevalence is near 0, all the deaths of those trials were in the ivermectin group (again, small event rates though).

I could re-do the analysis with the new data even with his critiques of how he thinks it should be done (which is highly debatable) but I didn’t end up doing it because at this point it would be an historical debate since the world has moved on from the topic. There are other points of course, there’s quibbles line by line.

I find Alexandros’ adjustment for Brazil somewhat convincing - not necessarily as a good adjustment, just in the sense that some adjustment needed to be done. I think the broader point is that results on the border of “statistical significance” often appear or go away depending on ambiguous decisions about coding single cases.

Alexandros realizes this and includes a more gestalt style chart directly showing the correlation, which he says goes below the significance threshold when you recode the Brazilian studies. This chart seems to be missing some studies which might change its conclusions; it was made by a third party and Alexandros is going to get back to me with more information. Dr. Bitterman adds that more recent American studies strengthen his hypothesis.

More discussion with Dr. Bitterman has also helped me better understand the context of this theory. Ivermectin does worst in studies of intermediate clinical endpoints: hospitalization, ICU admission, recovery time. It does best in studies of viral clearance rate and mortality. Viral clearance rate is a weak preclinical endpoint: not only is it especially susceptible to biases and file drawer effects, but it’s not that interesting unless it affects later clinical outcomes; many drugs change secondary endpoints but fail to change the things we care. Mortality is (usually) a strong and important endpoint; apparent positive results of ivermectin here require an explanation. The Strongyloides hypothesis tries to provide it.

But I erred on my earlier post by holding it up as “the” explanation for a large and heterogenous group of studies which were mostly looking at endpoints other than mortality, or as a counter to ivmmeta’s analysis which found positive results everywhere for everything through statistical incompetence.

I think I implicitly believed a stronger version of the worm hypothesis - that even in places without literal Strongyloides literally killing you, some people had some parasitic worms that were holding them back, ivermectin killed those worms, and that made them healthier overall and better able to deal with COVID. But nobody has asserted or defended that hypothesis and there’s no evidence for it. When I asked Dr. Bitterman, he pointed out that the opposite was at least as credible: parasitic worms depress the immune system, but immune overreaction is a major cause of death in COVID, so getting rid of them could make things worse rather than better.

The original post should have explained this hypothesis better, devoted less emphasis to it, and focused more on publication bias and other issues that could explain the overall result. In some cases, these issues would have shed more light on the mortality statistics too.

On my original post, I wrote:

Parasitic worms are a significant confounder in some ivermectin studies, such that they made them get a positive result even when honest and methodologically sound: 50% confidence

In retrospect this is framed too weakly - “significant” in “some” studies is compatible with irrelevant overall. Still, sticking to the spirit of what I meant, I think I would lower this guess to more like 35% now , and lower my overall estimate of how much of the mystery it explains even further.

I’m not an expert on this, you shouldn’t care about my exact probability, and I’m only mentioning it to communicate clearly and try to hold myself accountable.

V. Publication Bias

Alexandros has various arguments against funnel plots in general, and Dr. Bitterman’s funnel plot in particular. Some of these arguments are reasonable, but taken together they would discredit 95 - 100% of all funnel plots everywhere. Trying to destroy the whole institution of funnel plots just because one of them disagrees with your hypothesis is . . . honestly a move I have to respect. I agree that these provide Bayesian evidence, rather than 100% irrefutable evidence, of publication bias, and need to be considered in the context of everything else going on. After doing that, I still think they’re publication bias.

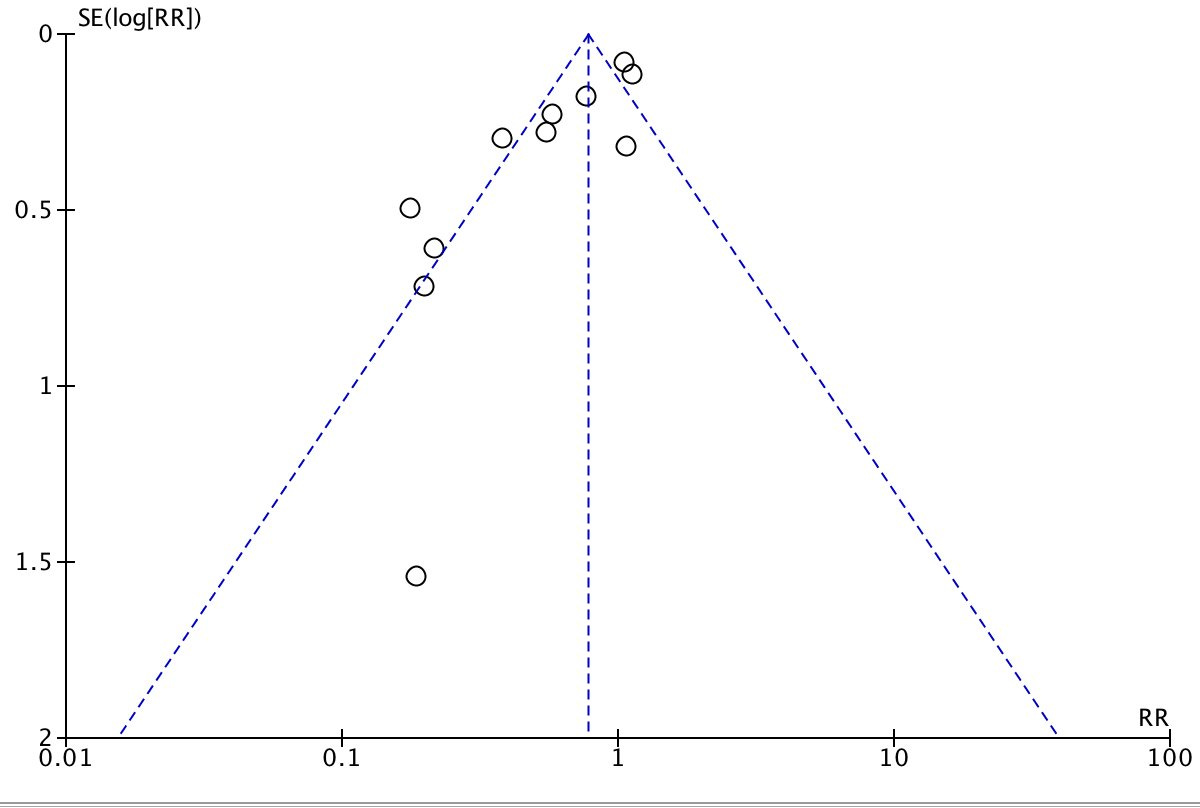

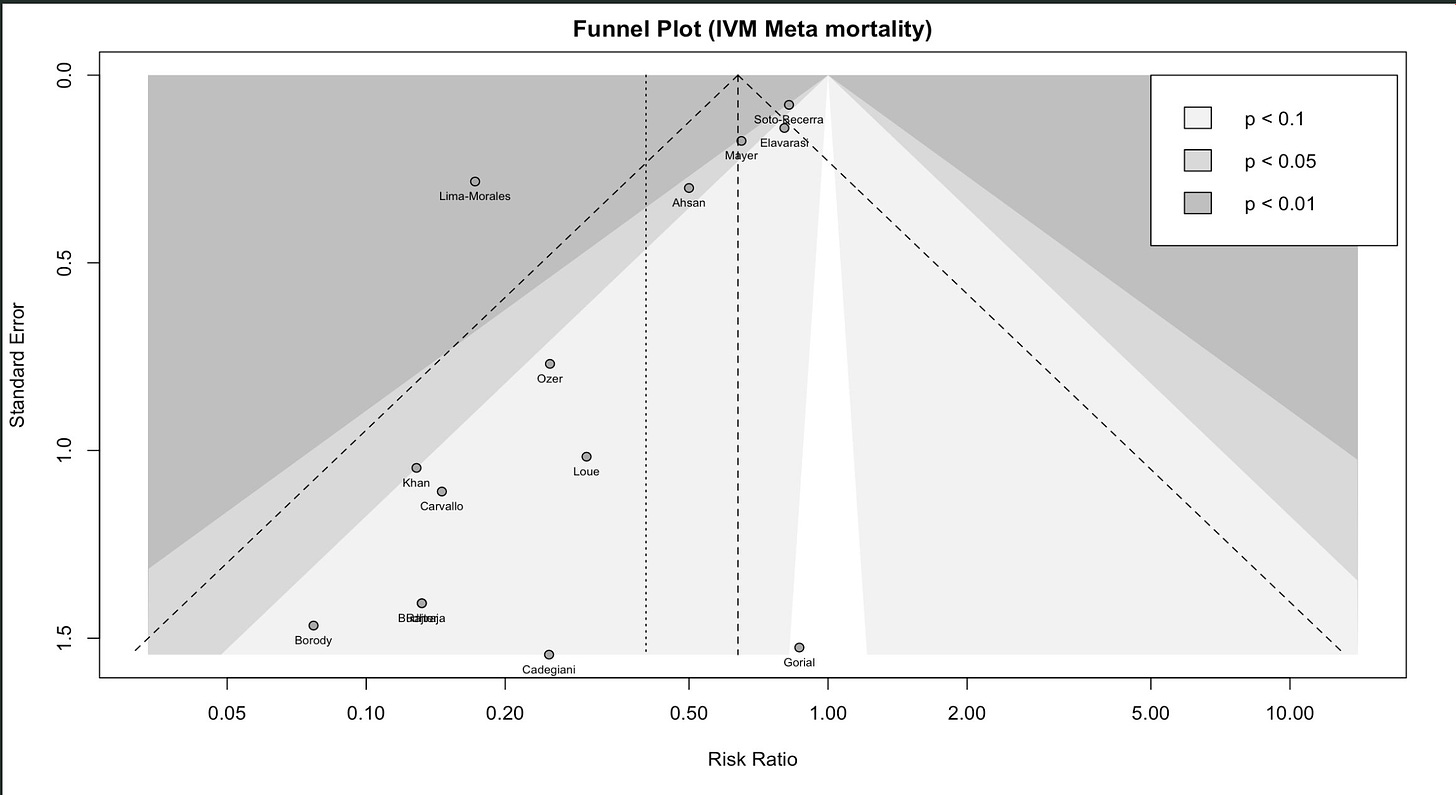

That makes publication bias more important. In the original post, I included this funnel plot from Dr. Bitterman:

In case you haven’t seen one of these before: this plots how big an effect the study found (horizontal axis) against study size (vertical axis). Studies that find ivermectin had no effect are at the center (RR = 1), studies that find a strong curative effect are to the left, studies that find a strong harmful effect are to the right.

When all studies are good, we have no reason to expect a correlation between study size and ivermectin efficacy - any deviations from the true effect should be random. This would look like a triangle centered around the true effect of the drug, with an equal number of studies on both sides.

When there is a lot of publication bias, we should expect that small studies get published only if they find exciting results, and big studies get published regardless (because a lot of work went into them, someone will want to publish them, and journals will accept them regardless of how exciting they are). So here you would expect to see big studies around zero, and an asymmetric tail of smaller studies heading in the more-exciting direction. This is what we see on Dr. Bitterman’s plot, suggesting strong publication bias for ivermectin results.

Alexandros’ full counterargument is here. Trying to sum it up:

-

Funnel plots can sometimes look deceptive, or be misreported, and are generally suspect.

-

Between-study heterogeneity can sometimes mimic publication bias (he has a nice graphic that makes this intuitive). The studies in the funnel plot have high heterogeneity.

-

For example, there is heterogeneity in when studies took viral loads, and on visual inspection that seems to explain some of the funnel plot.

-

We got most of the studies listed in this analysis from ivmmeta, which is not a journal and tries to include all studies it knows about, including preprints. We have studies like Carvallo and Borody which are more like informal writeups about what happened than formal papers. “Publication bias” here would have to mean that someone hid the fact that their study happened at all - a stronger bar than just “a journal didn’t publish it”.

My response to Point 1: Funnel plots are a widely-, almost universally- used tool in meta-analyses. Alexandros has found some finicky statisticians saying that maybe they are bad, but for any statistical test there are finicky statisticians saying that maybe they are bad. Alexandros says that Dr. Bitterman’s funnel plot fails standards laid out by a 2006 Ioannidis paper, but that paper says that 95% of funnel plots in the Cochrane database (considered an especially high-quality database of meta-analyses) would fail its standards.

When John Ioannidis attacks funnel plots, I am fine with this because Dr. Ioannidis is known to be unusually rigorous and this is part of his pro-rigor crusade. But when Alexandros gets angry at me for rejecting Borody et al, whose control group was “we got a control group from somewhere, it had 10x the normal hospitalization rate, don’t ask questions” - or thinks it’s offensive to suspect Carvallo, whose statistical analysis was “the person I claim was my statistician denies ever having been associated with me and explicitly accuses me of lying, but whatever, here are some numbers proving that zero people who took ivermectin died” - then I don’t think he can fairly demand Ioannidean levels of rigor when it serves him.

(am I incorrectly switching from truth-seeking to social-fairness-games? Probably partly, but I also think a part of truth-seeking is to apply the same level of rigor to all evidence. If we demand infinite rigor on both sides, nothing will ever pass our bar. If we demand zero rigor on both sides, we’ll be left with lots of confusing garbage. There are many defensible points on the how-much-rigor-to-demand continuum, but whichever one you choose it’s important to stick with it on both ends. This is especially true when we’re not expert statisticians and some of what we’re debating is which sources to trust and which tests are acceptable.)

Points 2 - 3 are worth taking seriously. These studies definitely have lots of heterogeneity. It’s why we’re having this discussion at all - if all studies agreed, then ivermectin would obviously work/fail and it wouldn’t be a controversy.

An asymmetric funnel plot shows that something unusual is going on. Publication bias is one common kind of unusual thing that causes this pattern. Therefore, asymmetric funnel plots provide evidence for publication bias. But they don’t prove it. Other things like heterogeneity can produce the same pattern. If Alexandros’ point is that we need to think clearly about whether an asymmetric funnel plot shows publication bias or something else, his point is well taken.7

But in this case, it’s probably publication bias. An exciting new medication for a deadly pandemic, where it would be revolutionary if it worked, but also boring and obvious if it didn’t, and which is originally tested mostly in small trials - is a situation perfectly designed to elicit publication bias.

Alexandros presents two arguments for why publication bias is unlikely.

First, our selection of studies comes from IVMMeta, a site that included not just published articles but preprints and vaguely-written-up summaries of experimental results. This removes one source of publication bias: bias in what journals choose to publish. But it doesn’t remove another: bias in what studies get written up, even at the vague summary level. I asked Dr. Bitterman for his assessment of how often this happens; he says it’s very common, even with medium-sized studies. When I pressed him on how medium-sized, he says he knows institutions that might not publish a hundred-person RCT if its results were too boring. Most of the studies on IVMMeta were smaller than that, so publication bias is still likely.

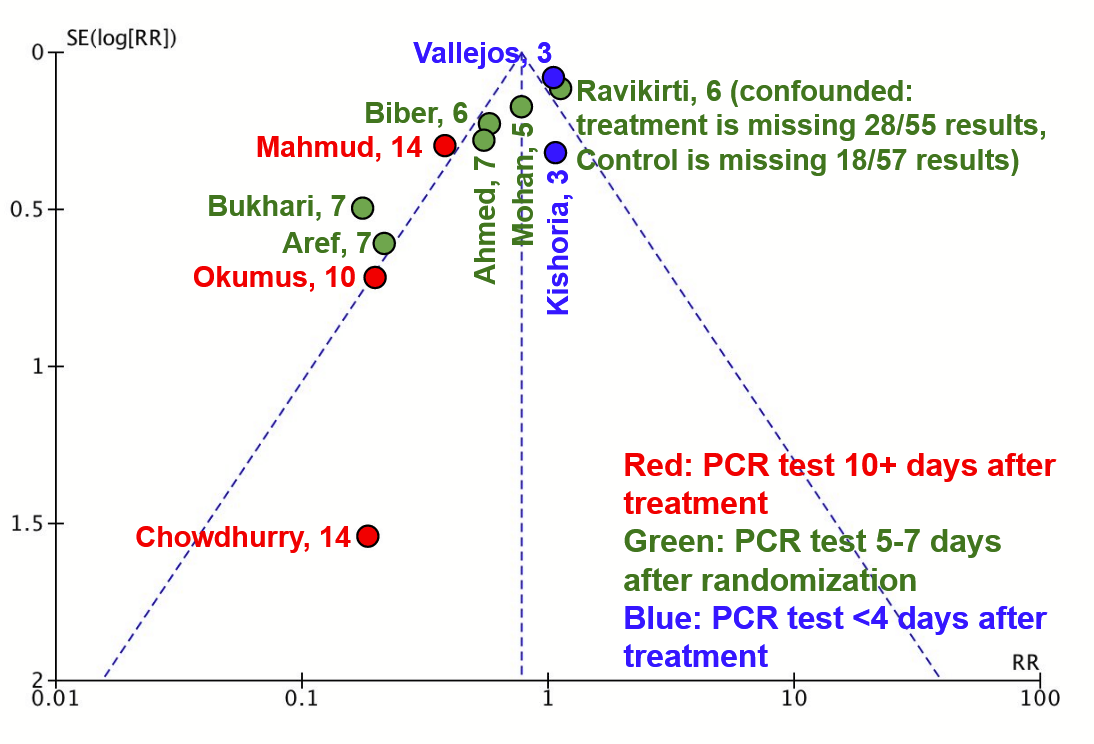

Second, he thinks he has found a specific example of heterogeneity:

Red studies (late testing) seem disproportionately on the left compared to blue studies (early testing). Here’s my contribution to the effort:

I think this is at least as convincing. I don’t think Alexandros would disagree - part of his point is that with so few studies, you can support any kind of heterogeneity you want. He hasn’t so much found real heterogeneity, as shown that with a funnel plot of so few studies, you never know.

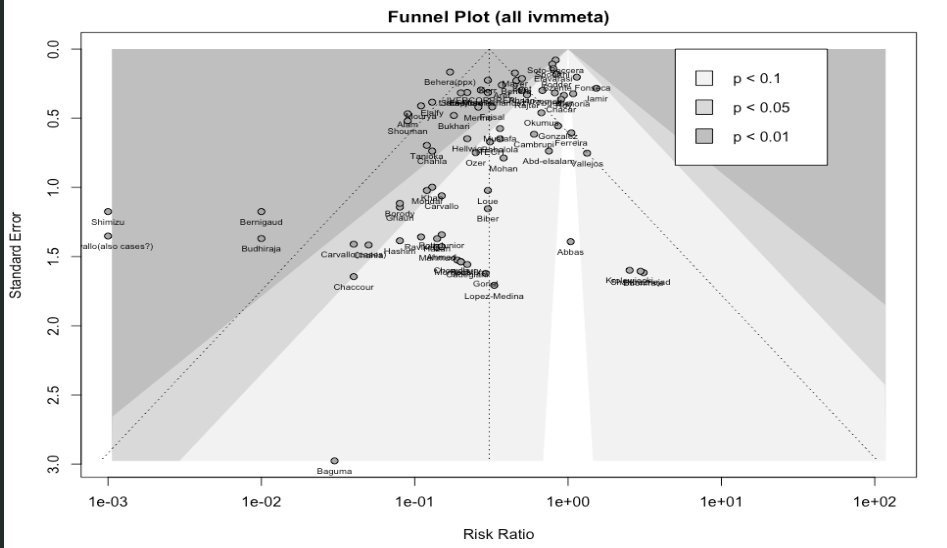

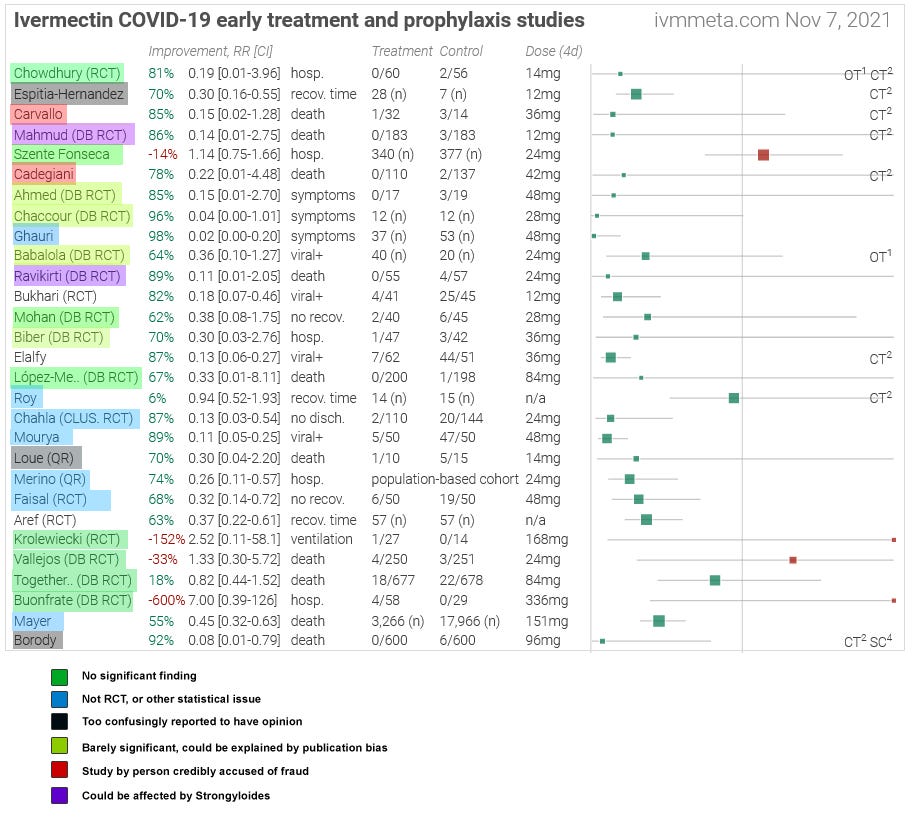

This funnel plot shows the viral clearance results. This is important because it’s one of the areas where ivermectin studies have most commonly found a signal of efficacy. But Dr. Bitterman has also looked for publication bias in ivermectin studies overall. For example, here’s a plot of all studies on IVMMeta.com:

Here’s just the mortality studies:

These aren’t confounded by day of PCR test (they’re mostly not testing PCR)8, but they’re at least as skewed as the PCR plot. Either by coincidence every funnel plot about ivermectin results that you can generate is confounded by a different kind of heterogeneity, or this area with high incentives for publication bias, investigated by types of studies where publication bias is extremely likely, has publication bias.

VI. What’s Happened Since 2021?

Since I wrote my post, several new ivermectin studies have come out.

I briefly looked to see if there were more small positive trials of the type analyzed above, but didn’t find too many of them. Studying ivermectin unsurprisingly seems to have gone out of vogue among ordinary doctors (or I’m getting worse at finding the studies).

But there were three new big RCTs - I-TECH from Malaysia, and ACTIV-6 and COVID-OUT from the United States. All three found no effect. With these studies (notably from low-parasite areas) meta-analyses of mortality no longer show any effect.

You can read Alexandros’ criticisms of ACTIV-6 trial here (1, 2, 3, 4), and his criticisms of I-TECH here. I don’t think he’s criticized COVID-OUT yet, but I’m sure it’s only a matter of time.

However skeptical you were of ivermectin efficacy in 2021, you should be more skeptical now.

It’s not directly related to ivermectin, but around the same time some studies seemed to show that another medication, fluvoxamine, did treat COVID effectively. I welcomed those studies and said that, although they had not yet firmly proven that fluvoxamine worked, the risk-benefit ratio was high enough that doctors should prescribe it and patients should ask for it. Later trials, including some of the same ones that found no effect for ivermectin, also found no effect for fluvoxamine. I no longer believe that fluvoxamine is likely to help COVID. The whole “repurpose existing drugs against COVID” idea seems to have been a big wash.

VII. Conclusions

a.

I ended my original post by saying I had 85 - 90% confidence that ivermectin didn’t have clinically significant effects. After a year, I’m upgrading that to 95% confidence, for a few reasons.

First, the many new well-done negative trials that have come out, mentioned above.

Second, the better visualizations of publication bias, that have convinced me that this is more of a problem than I previously thoughts.

This graph doesn’t think it’s a visualization of publication bias. But it shows that IvmMeta’s methodology gets positive results for basically any random drug or supplement thrown at it. Alexandros points out the ivermectin does better than any of the others (except quercetin, which has low n). But any process that spits out random positive results will have one of its random positive results be the highest. My conclusion is that the procedure that produced this graph is totally inadequate for telling us anything. And the most likely explanation for why this would happen again and again, across so many different substances, is publication bias.

This graph doesn’t think it’s a visualization of publication bias. But it shows that IvmMeta’s methodology gets positive results for basically any random drug or supplement thrown at it. Alexandros points out the ivermectin does better than any of the others (except quercetin, which has low n). But any process that spits out random positive results will have one of its random positive results be the highest. My conclusion is that the procedure that produced this graph is totally inadequate for telling us anything. And the most likely explanation for why this would happen again and again, across so many different substances, is publication bias.

Third, feeling like all of this analysis has actually gotten somewhere. I started looking into this because I wanted to know why studies so often fail, or return contradictory results. I appreciated the perspective Dr. Bitterman relayed to me on this, which is - come on, this always happens, we do Phase 1 trials on a drug, it looks promising, and then we do Phase 3 trials and it fails, this is how medicine works. He’s right and this is the correct attitude towards drug development.

But in other fields - the one that comes to mind now is declining sperm count, which I’m trying to write an article on - there aren’t the equivalent of Phase 3 trials. Just a hodgepodge of smaller or bigger studies, probably about as good as the ones that find ivermectin improves viral clearance, producing a hodgepodge of noisy results. Then some statistician draws a line through the noise and tells us the line is pointing up and that means we should be worried. Should we? What about silexan for anxiety? There are five studies - better than the worst ivermectin studies, but nowhere close to Phase 3 - and they find positive results. Silexan would revolutionize the treatment of anxiety and help avoid medications with much worse side effects. Do I start recommending it as a first line treatment?

My first post was very limited progress towards this goal; I felt able to make the case ivermectin wasn’t useful, but not to explain why so many studies found the opposite. I feel slightly more confident now…

…that I have reasonable explanations for what went on in about 26 of the 29 studies. Two of the remainders - Aref and Elalfy - give off gestalt vibes of untrustworthiness. The last one, Bukhari, remains mysterious. It’s a viral clearance study, and this is an area without lots of publication bias. But it got results p = 0.001, and you would need a thousand studies in file drawers to produce one like that. Weird.

b.

Alexandros has wrestled with these same problems, but solved it differently. He’s looked for (and found, as per his judgment) flaws in the few big trials, which lets him keep most of the rest. I haven’t read his whole corpus on this, but am generally not impressed. He does find some issues, but all trials will have some minor errors or ambiguities. And the big trials will have more documentation you can look through to find things to nitpick or be confused.

Alexandros has previously stressed that he doesn’t mean to express certainty that ivermectin works. He calls his style of reasoning Omura’s Wager, by reference to Pascal’s Wager. If you use ivermectin, and it doesn’t work, then you’ve wasted your time and maybe gotten a few minor side effects. If you don’t use ivermectin, and it does work, then you’ve missed out on a potentially life-saving medication. Therefore (he concludes) given even a little remaining uncertainty about whether ivermectin works, you should use it.

This isn’t how mainstream medicine thinks about this in any other context, and if true it’s much more interesting than a debate around one particular repurposed dewormer. I try to respond in Pascalian Medicine. But since then, there’s been more evidence that ivermectin at the doses used in COVID studies might be harmful. Both the I-TECH study and Dr. Bitterman’s analysis found more severe side effects in ivermectin groups compared to placebo. Not only does this challenge ivermectin in particular, but using it as a test case calls Omura’s Wager into question more generally.

Acknowledging that the Wager debate is interesting, I also asked Alexandros to, gun-to-his-head, tell me how likely he thinks it is ivermectin works. To his credit, he gave a clear response:

I’ll try to answer the question I think you’re asking: Whether I’d expect a sufficiently-powered, high-quality study (say, something that cloned the protocol used for testing Paxlovid in the EPIC-HR trial, and dosed ivm similarly to how FLCCC recommends) to produce a 10% or higher drop in mortality for high-risk patients. I’d guess we would have seen that kind of reduction or more in that kind of trial at that time, yes.

It does seem that TOGETHER, despite the many ways it deviates from what I described above, showed something in that range (12% reduction in mortality), though of course with too low an event/patient number to make it definitive.

However, you’re asking me about today, and in the US. Given current mortality rates, you’d need something much bigger than EPIC-HR to see a clear mortality benefit these days, and this is true regardless of the drug being tested. So the absolute steelman of your question may be something like: If someone re-ran EPIC-HR for ivm as described above, but with 10k patients (of similar characteristics as the ones they got in EPIC-HR), would I bet even money that they’d see “statistically significant” 10% reduction in mortality? Thinking about it as hard as I can, If I felt I could trust the scientists to not pull any dirty tricks, I think I still would, yes.

I said 5% above, so it seems like we still haven’t converged. Sad!

c.

I made several mistakes in the first version of this post:

First, I made a major mistakes on one of the studies I looked at (Biber).

Second, I was directionally correct on others, but too quick to accuse people of fraud on data that was merely suggestive, and to mock them for it. Nobody can be right all the time, but I try not to be simultaneously wrong and smug. I failed at that here and need to do better at Principle of Charity, even when looking at twenty-nine boring and often terrible studies one after the other until my brain turns to mush.

Third, I messed up the informal “meta-analysis”. I said in the post it was probably wrong and I was just churning something out to get a vague idea, but it was still embarassing and (weakly) misleading.

Fourth, I probably overemphasized the importance of worms, and underemphasized the importance of publication bias. This left me confused about some non-mortality-related results, and overall more confused about the literature and less willing to dismiss ivermectin than I should have been.

Realistically, this project was outside my expertise and competence level.

But I’m not exactly apologizing for publishing it. I think the discourse on this was terrible. The mainstream media just repeated that Elgazzar was a fraud, again and again, without mentioning the dozens of other studies that found positive effects of ivermectin. Academia knew what it was doing, but mostly failed to communicate their reasoning to the public, beyond giving short snippets for interviews harping yet again on how Elgazzar was a fraud. A few data detectives and epidemiologists with Twitter accounts took potshots at specific claims, but almost never in a way that explained the bigger picture (Dr. Bitterman was the main exception).

In contrast, the pro-ivermectin side did an amazing PR job. IVMMeta was tireless, fantastically designed, and presented exactly the kind of gestalt picture nobody else bothered to touch. Alexandros dedicated much of his time over two years filling in details of the pro-ivermectin case and gathering a network of amateur epidemiological detectives contributing to the effort. This replicates a pattern I’ve seen again and again: the mainstream shies away from deep analysis of contrarian theories, not wanting to dignify them with tough analysis, while obsessive contrarians produce compelling and comprehensive guides to their side of the argument.

I wanted to gather a gestalt argument for the consensus in one place and help relieve this embarrassing state of affairs. I give myself a C+ for results but an A for effort. I wish other people would do this so I could stay in my lane of sniping at people with bad opinions about antidepressants.

I appreciate everyone who helped gather this information, question its assumptions, fortify key points, and beat it into shape, including Alexandros.

I appreciate this. I acknowledge he did not literally insult my intelligence in so many words, but I found paragraphs like:

Scott starts out confused about whether this trial is an RCT. His confusion is somewhat puzzling, given that the paper says it’s “non-randomized” in several places. In particular:

…in the abstract

…in the first line of section 2

…in the first line of section 3.2

…at the end of the discussion section. They literally have the following sentence: “Study limitation: the groups were not randomized and the drug combination does not have an established in vitro mechanism of action and remains exploratory.”

How else were the authors supposed to make this clear?

…pretty grating, given that I don’t feel like Alexandros understood or responded to the reasons why I was uncertain about how random this trial was.

I agree it’s in some sense unfair if I use introduction of new data mid-argument to defend myself, and I don’t mean to do that. I do think it’s always fair to get new data to try to resolve the original question. And if it turns out a theory was right about the original question, this does sort of defend the at least the spirit of the theory, if not its implementation.

-

Alexandros responds: “These are quotes by a local official who is involved in the case. They’re not the BMJ’s opinion. I believe, but am not sure, that Cadegiani is in a legal dispute with this peroson. And in any case, they’re non-factual and hyperbolic. I can only look at the facts of the matter. The fact that this official is making hyperbolic statements can be interpreted as an argument on either side of the debate.”

-

Alexandros responds: “This is extremely common in studies, and accepted as normal. TOGETHER is missing ‘time since symptom onset’ for 23% of its patients, and age for 7% of its patients. Each of these are inclusion criteria, so one wonders how these patients were even included in the first place. And yet, nobody bats an eyelash. In principle, I have no objection if one wanted to make “missing data” a factor to filter by, but then every study has to be looked at the same way, not just Babalola. More here.

-

Alexandros adds: “This is from the buzzfeed piece: ‘Javier Farina, an infectious diseases doctor at Hospital Cuenca Alta and a member of its ethics committee, acknowledged that staff members may have individually participated and noted that it is common in Argentina for employees to work at different hospitals.’ – I don’t think this one is ‘according to Carvallo’. Surely Buzzfeed has to substantiate that there is in fact an issue with an adult medical professional enrolling in a study of their choice.”

-

Alexandros writes: “I checked the original, and I’m not sure what this is referring to. Was I irritated when I was writing this? Sure. But I don’t see any case where I make any aspersions about your intelligence or fling any insults whatsoever. If I did write something along those lines, please point it out. I tried quite hard to keep my tone as neutral as I possibly could, but I can see how something may have slipped.”

-

Alexandros writes “But patients who come in the weekend can totally differ systematically from patients who come in the weekdays.” First, I think (though this is very speculative) that the trial used a six day week to avoid Friday, the Muslim equivalent of the weekend. Second, although this is a possible source of bias, it’s a pretty weak one, and I’m still interested in whether the only source of bias is weekend vs. weekday, or whether this is actually nonrandom in some more general sense.

-

Alexandros writes: “Given that these new trials were mostly in late ‘21 and ‘22, and the mortality in them was extremely low, I don’t believe they would alter the results of my analysis, since studies with few if any events get very low weights in this style meta-analysis. I haven’t re-run it, but if it will make a difference, let me know and I’ll give it a go. I also think (but won’t take it the wrong way if you ignore me on this) it is unfair to introduce new data mid-argument. As you probably know, I have serious objections about these negative American studies (the most serious of which I have not yet published) and believe they are worthy of a separate conversation. My point, i believe, has consistently been that the confidence people are projecting that ivm doesn’t work isn’t supported by the evidence. either strongyloides was particularly strong as an explanation at the time, or there were other hypotheses we should have considered.”

-

Thanks to Dr. Bitterman for helping clarify this

-

See here for a separate look at timing as a confounder.