Some Unintuitive Properties Of Polygenic Disorders

E. Fuller Torrey recently published a journal article trying to cast doubt on the commonly-accepted claim that schizophrenia is mostly genetic. Most of his points were the usual “if we can’t name all of the exact genes, it must not be genetic at all” - but two arguments stood out:

-

Even though twin studies say schizophrenia is about 80% genetic, surveys of twin pairs show that if one identical twin has schizophrenia, the other one only has a 15% to 50% chance of having it.

-

The Nazis ran a eugenics program that killed most of the schizophrenics in Germany, eliminating their genes from the gene pool. But the next generation of Germans had a totally normal schizophrenia rate, comparable to pre-Nazi Germany or any other country.

I used to find arguments like these surprising and hard to answer. But after learning more about genetics, they no longer have such a hold on me. I’m going to try to communicate my reasoning with a very simple simulation, then give links to people who do the much more complicated math that it would take to model the real world.

Let’s start with the identical twin concordance. If you have schizophrenia, there’s only a 15% - 50% chance your identical twin has it too. Does that really fit a condition which is supposedly 80% genetic? Shouldn’t it be an 80% chance? Or at least higher than 15%?

No. I ran a discount-rate simulation on a spreadsheet. I generated 2000 people. I gave each of them a genetic risk score and an environmental risk score - both random numbers between 0 and 1.

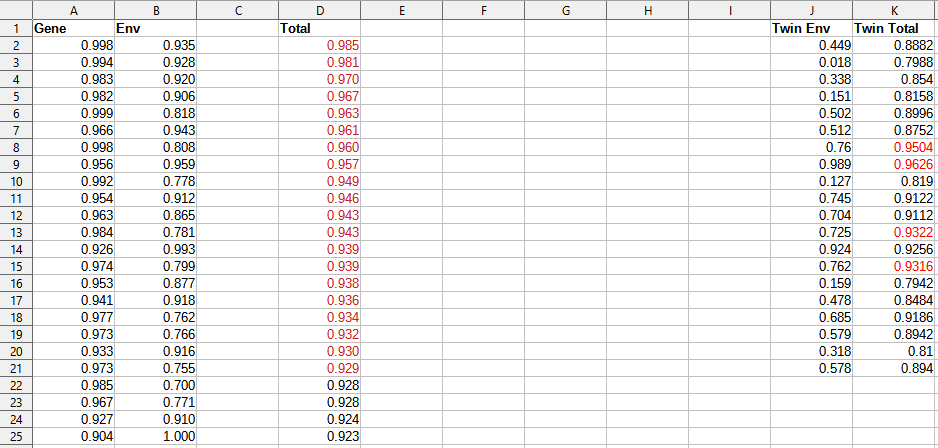

Then I created a total risk score which was the average of their genetic and environmental scores, with the genetic weighted 4x more highly than the environmental, ie [((4 * genetic) + (environmental))/5]. In other words, the genetic score contributed 80% of the variance. It looked like this.

[EDIT: My bad, it should be 2x, but this shouldn’t change the overall direction of the results1]

Since 1% of the population is schizophrenic, I sorted by total risk score and declared the top 20 out of these 2000 people to be schizophrenics.

This produced a threshold of 0.928 - in this discount simulation, anyone with a higher total risk score than that got the condition.

Then I generated an “identical twin” for each schizophrenic: another person who had the same genetic risk score, but a new random environmental risk score. I computed total risk score [((4 * genetic) + (environmental))/5] for the second twin.

We see here that only four of the twenty twins pass the 0.928 threshold for schizophrenia - a 20% rate. This fits well within the 15% - 50% rate we find in real life.

Since our simulation says genes matter 4x more than environment, how come the identical twins of schizophrenics (who have the same genes) are so unlikely to have the condition?

Look at the screenshot above again, and notice the genetic and environmental risk scores of the original twenty schizophrenics. By sorting for total risk, we select very heavily on genetic risk, which matters four times more - and so we see numbers like 0.998, 0.994, 0.983, etc. But we’re still selecting somewhat on environmental risk, so we see numbers like 0.935, 0.928, and 0.920 (remember, average is 0.5). Schizophrenia is so rare that you need both high genetic and high environmental risk to get it.

Now go to the twins. By definition, they also have high genetic risk scores. But on average, they have average environmental risk scores. Most of them don’t cross the 0.928 threshold unless the random number generator that determined their environmental risk score came up high. How high? In this simulation it had to be at least 0.725, and only 20% of the twins scored that high.

Is it wrong to give twins random environmental scores? Don’t twin pairs grow up in very similar environments? Yes - this is why I called this an overly simplified simulation that was just supposed to communicate the basic point. ACX commenter Metacelsus found a paper from 1970 that did the full calculations and predicts about 33% twin concordance for a disease like schizophrenia with 80% heritability and 1% prevalence. But I think even this isn’t exactly right; it depends on the balance between shared and non-shared environmental risks. Still, somewhere in the 15 - 50% range is probably reasonable.

What about the second argument, the one about the Nazis’ eugenics program?

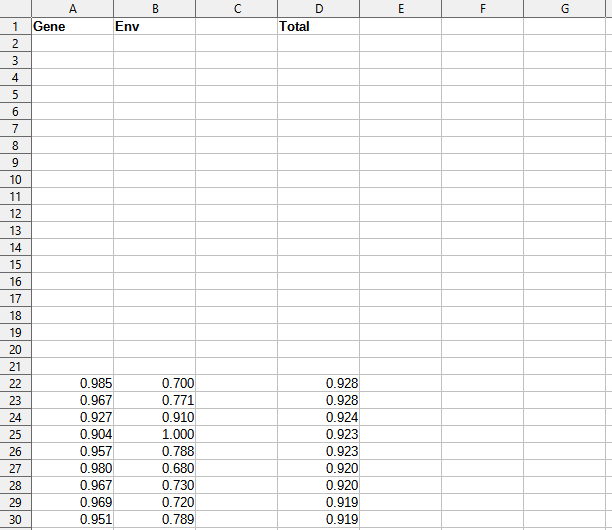

Here I took the same simulation and eliminated all the schizophrenics:

Making everyone mate is beyond the scope of this discount-rate simulation, so I just assumed everyone had a child who had the exact same genetic risk as themselves, but a new random environmental risk.

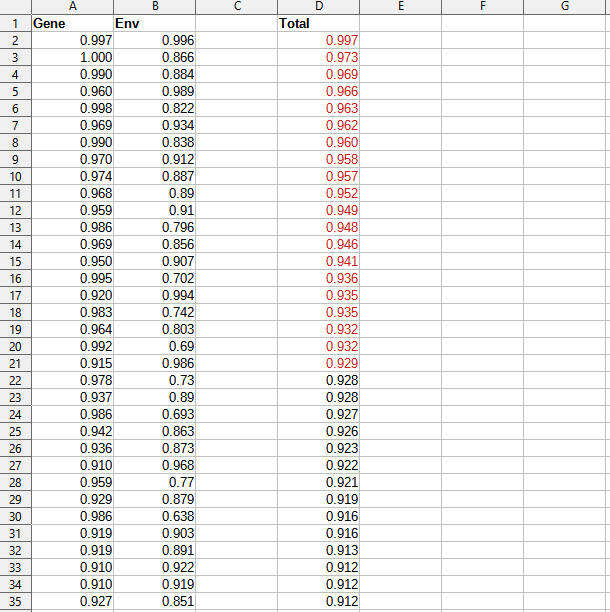

Then I sorted again, and called anyone with total risk > 0.928 a schizophrenic.

The new generation still has 20 schizophrenics - just as many as the last!

How can this be? The lowest genetic risk score of a person who nevertheless developed schizophrenia was 0.915. In our sample of 2000 people, we should expect about 183 people to be at or above that threshold. The simulated Nazis killed off 20 in the last generation. There are still 163 left. These are people who didn’t get schizophrenia because they had a positive environment, but could have gotten it if their environment had been worse. They outnumber schizophrenics by almost 10 to 1. When we bring their genes forward into the new generation, some of their descendants get bad environments, and so get schizophrenia. I think you should expect very slightly fewer schizophrenics in the new generation, but the effect size wasn’t noticeable in this small granular simulation - nor, apparently, in Germany2.

I can’t find a formal paper about this one. A better model would have to take into account that people’s children aren’t clones of themselves, and that children’s environment is correlated with their parents’. But at least the first one would drive rates up, not down, so I think this makes the point just fine.

People really hate the finding that most diseases are substantially (often primarily) genetic. There’s a whole toolbox that people in denial about this use to sow doubt. Usually it involves misunderstanding polygenicity/omnigenicity, or confusing GWAS’ current inability to detect a gene with the gene not existing. I hope most people are already wise to these tactics.

The two arguments above were the really novel ones that I found potentially convincing. But AFAlCT the mystery goes away once you think about them more formally.

Awais Aftab has a more interesting article about how even if the twin studies are right, “mostly genetic” is a poor way to describe their results. I disagree, and will try to respond to it some other time.

-

When I re-ran it with the correct 2x number, the twin concordance rate was 10%, and the second generation had 23 schizophrenics. This puts the twin concordance rate outside the observed amount, which I think is because I’m not accounting for twins having a shared environment; the linked paper accounts for that and finds 33%.

-

Probably because it’s hard to diagnose schizophrenia, and the change was below the noise threshold of whatever methods they used.