Somewhat Contra Marcus On AI Scaling

I.

Previously: I predicted that DALL-E’s many flaws would be fixed quickly in future updates. As evidence, I cited Gary Marcus’ lists of GPT’s flaws, most of which got fixed quickly in future updates.

Marcus responded with a post on his own Substack, arguing . . . well, arguing enough things that I’m nervous quoting one part as the thesis, and you should read the whole post, but if I had to do it, it would be:

Now it is true that GPT-3 is genuinely better than GPT-2, and maybe (but maybe not, see footnote 1) true that InstructGPT is genuinely better than GPT-3. I do think that for any given example, the probability of a correct answer has gone up. [Scott] is quite right about that, at least for GPT-2 to GPT-3.

But I see no reason whatsoever to think that the underlying problem — a lack of cognitive models of the world —have been remedied. The improvements, such as they are, come, primarily because the newer models have larger and larger sets of data about how human beings use word sequences , and bigger word sequences are certainly helpful for pattern matching machines. But they still don’t convey genuine comprehension, and so they are still very easy for Ernie and me (or anyone else who cares to try) to break.

And including a proposed bet!

I am willing to bet [Scott] now (terms to be negotiated) that if OpenAI gives us unrestricted access to GPT-4, whenever that is released, and assuming that is basically the same architecture but with more data, that within a day of playing around with it, Ernie and I will still be able find lots of examples of failures in physical reasoning, temporal reasoning, causal reasoning, and so forth.

I of course will not take that bet, since I agree that they will be able to find many problems.

To repeat, the main point I was making in my last post was that we should mostly expect certain particular minor problems with DALL-E to get fixed by the next update. I don’t think Marcus particularly wants to argue against that.

But I do think we have a more substantive disagreement that it’s worth fleshing out.

II.

Let’s start with a softball: I think, regardless of whether or not Marcus is right, he’s failed to provide evidence for his position.

Marcus says GPT’s failures provide evidence that purely statistical AI is a dead end. Quoting here:

Literally billions of dollars have been invested in building systems like GPT-2, and megawatts of energy (perhaps more) have gone into testing them; few systems if any have ever been trained on bigger data sets. Many of the brightest minds have been working on blank-slate-ish sentence prediction systems for decades.

In essence, GPT-2 has been a monumental experiment in Locke’s hypothesis, and so far it has failed. Empiricism has been given every advantage in the world; thus far it hasn’t worked. Even with massive data sets and enormous compute, the knowledge that it acquires has been superficial and unreliable.

Rather than supporting the Lockean, blank-slate view, GPT-2 appears to be an accidental counter-evidence to that view […]

GPT-2 is both a triumph for empiricism, and, in light of the massive resources of data and computation that have been poured into them, a clear sign that it is time to consider investing in different approaches.

GPT certainly hasn’t yet shown that statistical AI can do everything the brain does. But it hasn’t shown the opposite, either.

GPT-2 has ~1 billion parameters (a measure of neural network size). It failed on a lot of questions, as Marcus demonstrated.

GPT-3 has ~100 billion parameters. It did significantly better than GPT-2, but still failed on some different questions Marcus was able to find.

How many parameters does the human brain have? As I’ve said before, the responsible answer is that brain function doesn’t map perfectly to neural net function, and even if it did we would have no idea how to even begin to make this calculation. The irresponsible answer is 100 trillion.

So: a thing designed to resemble the brain, but 100,000x smaller, is sort of kind of able to reason, but not very well.

A similar thing designed to resemble the brain, but now only 1,000x smaller, does a noticeably better job at reasoning, although still not brain-level.

And from this progression, Marcus concludes . . . that this demonstrates nothing like this will ever be able to imitate the brain. What? Can we get a second opinion here?

I don’t want to definitively assert that a brain-sized GPT will definitely be just as good at reasoning as the brain. But I hardly think GPT’s performance provides strong evidence to the contrary.

What I’m describing is a version of the scaling hypothesis: GPT-like AIs get better with scale. The story of the past ~10 years of AI research has been everyone expecting this to break down (“okay, adding more layers made AIs smarter last time, but surely that same trick won’t work again!”) and the story of the past ~10 years of AI research has been that it just keeps going.

Marcus is admitting this: each GPT has been better than the one before. He even seems to predict this will continue a bit into the future - he expects OpenAI to release a GPT-4, and surely they wouldn’t release a new product if it wasn’t an improvement on the old. He just seems convinced that the improvements will stop sometime before human level. Why?

That is: suppose we created some ideal Platonic benchmark of every reasoning problem you might ask a human. Suppose GPT-2 got 20% of these right, and GPT-3 gets 40% of these right. Might some future GPT-X - not necessarily 4, but 5, or 10, or whatever - get 100% right? I don’t see how Marcus can rule this out: he can’t point to any specific kind of reasoning problem GPTs will never be able to solve. And he agrees that each generation of GPTs can solve more than the one before. So why shouldn’t GPT keep progressing until it gets 100%?

III.

My understanding of Marcus is that he’s going off some argument like this: GPT makes ridiculous mistakes that no human would make. This proves that it doesn’t have common sense - or, more technically some specific skill called “world-modeling”. If you could model the world, you would never make these kinds of ridiculous mistakes. Therefore, until someone figures out how to add in that skill, GPT will continue to be deficient. Even if hypothetically you feed it so much data that it can answer all reasoning problems, it’s doing something like a giant lookup table, and we shouldn’t be especially impressed.

My answer is: I think humans only have world-models the same way we have utility functions. That is, we have complicated messy thought patterns which, when they perform well, approximate the beautiful mathematical formalism.

I asked the local five-year-old the same questions that Gary Marcus asked GPT. She did a little better than GPT-3 (73% vs. 63%), but it was a close contest. Five-year-olds are known to be less good at practical reasoning than adults, but it’s not like they’re missing a brain lobe or neurotransmitter or anything. They’re just doing the same processes, only worse. Did this 5 year old have world-modeling ability, or not?

No five-year-olds were harmed in the making of this post. I promised her that if she answered all my questions, I would let her play with GPT-3. She tried one or two prompts to confirm that it was a computer program that could answer questions like a human, then proceeded to type in gibberish, watch it respond with similar gibberish, and howl with laughter.

No five-year-olds were harmed in the making of this post. I promised her that if she answered all my questions, I would let her play with GPT-3. She tried one or two prompts to confirm that it was a computer program that could answer questions like a human, then proceeded to type in gibberish, watch it respond with similar gibberish, and howl with laughter.

If I had more time and experimental subjects, I would like to ask people who are asleep the same questions, in their dreams (this is a perfectly valid experimental protocol! Konkoly et al asked people questions in their dreams, and it went fine!) I predict that dreamers would also do mediocre. For example, just before I got married, I dreamt that my bride didn’t show up to the wedding, and I didn’t want to disappoint everyone who had shown up expecting a marriage, so I married one of my friends instead. This seems like at least as drastic a failure of prompt completion as the one with the lawyer in the bathing suit, and my dreaming brain thought it made total sense.

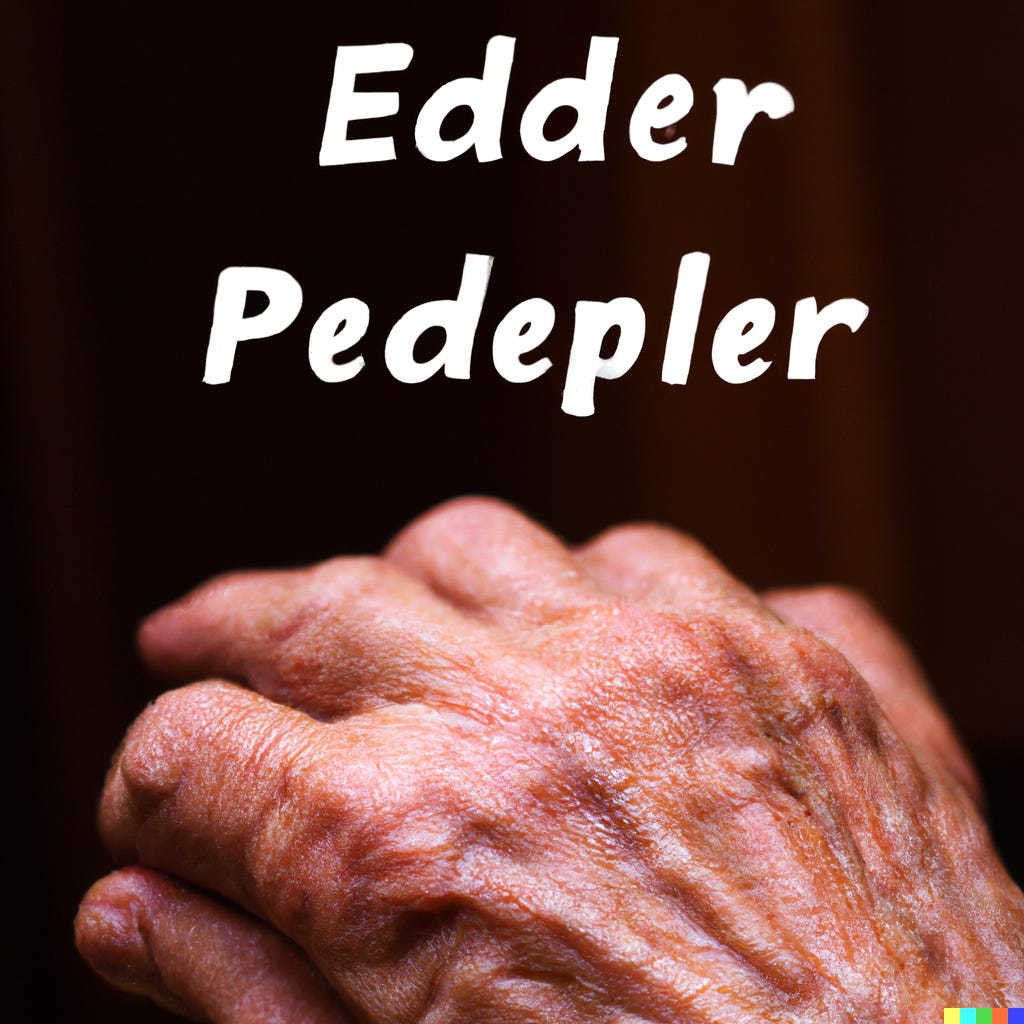

DALL-E, “A elderly person’s hand, labelled with the text ‘AN ELDERLY PERSON’S HAND’” Lucid dreaming enthusiasts suggest that two of the easiest ways to distinguish dreams from reality is that, in dreams, hands have the wrong number of fingers, and text is garbled and unreadable. This is not a coincidence because nothing is ever a coincidence.

DALL-E, “A elderly person’s hand, labelled with the text ‘AN ELDERLY PERSON’S HAND’” Lucid dreaming enthusiasts suggest that two of the easiest ways to distinguish dreams from reality is that, in dreams, hands have the wrong number of fingers, and text is garbled and unreadable. This is not a coincidence because nothing is ever a coincidence.

But even the waking world gives us clues, as Sarah Constantin notes in Humans Who Are Not Concentrating Are Not General Intelligences. Most adults will make GPT-like mistakes (or gloss over such mistakes) unless they’re focusing all their brainpower on an issue.

And a 4chan post by someone who claims to have done psych research in prison populations goes further (slightly edited for language and offensiveness):

I did IQ research as a grad student, and it involved a lot of this stuff. Did you know that most people (95% with less than 90 IQ) can’t understand conditional hypotheticals? For example, “How would you have felt yesterday evening if you hadn’t eaten breakfast or lunch?” “What do you mean? I did eat breakfast and lunch.” “Yes, but if you had not, how would you have felt?” “Why are you saying that I didn’t eat breakfast? I just told you that did.” “Imagine that you hadn’t eaten it, though. How would you have felt?” “I don’t understand the question.” It’s really fascinating […]

Other interesting phenomenon around IQ involves recursion. For example: “Write a story with two named characters, each of whom have at least one line of dialogue.” Most literate people can manage this, especially once you give them an example. “Write a story with two named characters, each of whom have at least one line of dialogue. In this story, one of the characters must be describing a story with at least two named characters, each of whom have at least one line of dialogue.” If you have less than 90 IQ, this second exercise is basically completely impossible. Add a third level (‘frame’) to the story, and even IQ 100’s start to get mixed up with the names and who’s talking. Turns out Scheherazade was an IQ test!

Time is practically impossible to understand for sub 80s. They exist only in the present, can barely reflect on the past and can’t plan for the future at all. Sub 90s struggle with anachronism too. For example, I remember the 80-85s stumbling on logic problems that involved common sense anachronism stuff. For instance: “Why do you think that military strategists in WWII didn’t use laptop computers to help develop their strategies?” “I guess they didn’t want to get hacked by Nazis”. Admittedly you could argue that this is a history knowledge question, not quite a logic sequencing question, but you get the idea. Sequencing is super hard for them to track, but most 100+ have no problem with it, although I imagine that a movie like Memento strains them a little. Recursion was definitely the killer though. Recursive thinking and recursive knowledge seems genuinely hard for people of even average intelligence.

I have no proof that this person is who they say they are, but it matches some of my experience giving cognitive exams to patients from low-functioning populations. And it matches Flynn on Luria (who admittedly was approaching IQ from a cultural relativist viewpoint, but one which I think is equally applicable to the current problem). Luria gave IQ-test-like questions to various people across the USSR. He ran into trouble when he got to Uzbek peasants (transcribed, with some changes for clarity, from here):

Luria: All bears are white where there is always snow. In Novaya Zemlya there is always snow. What color are the bears there?

Peasant: I have seen only black bears and I do not talk of what I have not seen.

Luria: What what do my words imply?

Peasant: If a person has not been there he can not say anything on the basis of words. If a man was 60 or 80 and had seen a white bear there and told me about it, he could be believed.

And:

Luria: There are no camels in Germany; the city of B is in Germany; are there camels there or not?

Peasant: I don’t know, I have never seen German villages. If is a large city, there should be camels there.

Luria: But what if there aren’t any in all of Germany?

Peasant: If B is a village, there is probably no room for camels.

And:

Luria: What do a chicken and a dog have in common?

Peasant: They are not alike. A chicken has two legs, a dog has four. A chicken has wings but a dog doesn’t. A dog has big ears and a chicken’s are small.

Luria: Is there one word you could use for them both?

Peasant: No, of course not.

Luria: Would the word “animal” fit?

Peasant: Yes.

And:

Luria: What do a fish and a crow have in common?

Peasant: A fish — it lives in water. A crow flies. If the fish just lies on top of the water, the crow could peck at it. A crow can eat a fish but a fish can’t eat a crow.

Luria: Could you use one word for them both?

Peasant: If you call them “animals”, that wouldn’t be right. A fish isn’t an animal and a crow isn’t either. A crow can eat a fish but a fish can’t eat a bird. A person can eat fish but not a crow.

What I gather from all of this is that the human mind doesn’t start with some kind of crystalline beautiful ability to solve what seem like trivial and obvious logical reasoning problems. It starts with weaker, lower-level abilities. Then, if you live in a culture that has a strong tradition of abstract thought, and you’re old enough/smart enough/awake enough/concentrating enough to fully absorb and deploy that tradition, then you become good at abstract thought and you can do logical reasoning problems successfully.

(Sometimes! If you’re lucky! Linda is a blah blah blah you know the story. Is she more likely to be a bank teller, or a feminist bank teller. When people get this question wrong, do they have a world-model, or not?)

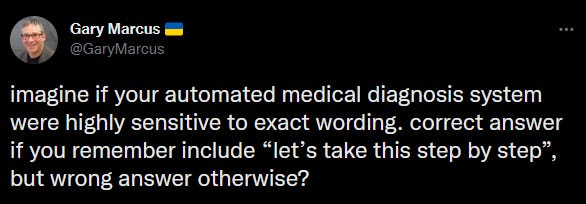

Imagine a world where doctors gave different diagnoses based on unrelated contingent features of the encounter like a patient’s gender, their race, or how you phrase the question. What a crazy place that would be!

Imagine a world where doctors gave different diagnoses based on unrelated contingent features of the encounter like a patient’s gender, their race, or how you phrase the question. What a crazy place that would be!

What is the pre-logical function that logic gets knit out of? I think it’s something like predictive pattern-matching. I think the brain starts by predicting arbitrary patterns, builds up more and more layers of abstraction to try to predict those patterns better, and eventually some of those layers cohere into something that looks like formal logic.

To put it another way, my brain is in some sense a supercomputer that can outperform the best calculating machines in the world - but also, I have trouble multiplying three digit numbers in my head. The supercomputer is doing something , and then I’m using that something, very lossily, to emulate logical functions like math or formal logic. So when I see GPT, which also runs on a supercomputer, also slowly gaining the ability to multiply two-digit, then three-digit numbers as the supercomputer gets bigger and bigger, I feel a sort of kinship with it. It’s a trash heap of patterns with a hard-won ability to sometimes break out into the clear day of logical reasoning, just like me.

IV.

I think Marcus knows and agrees with most of this, but I think he thinks of the world-modeling ability as some special rare brain region (maybe the prefrontal cortex?) which is only online part of the time (or maybe can have its performance degrade gracefully). Whereas I think of it as shallower pattern-matching abilities which escalate to deeper and deeper pattern-matching abilities as more and more brainpower becomes available, with world-modeling as one of the deepest (and sure, probably the PFC plays a major role, but not because it has a fundamentally different structure but just because that’s where reinforcement learning stuck the highest-level patterns). Why do I think this?

The human brain is pretty plastic. Usually if one part of it dies, another part can take over. This makes me think that the brain area : function correspondence isn’t entirely a function of different structures in different regions (though some of it might be this), but downstream of an originally poorly-differentiated blob of neurons that get trained by the overall predictive structure based on their proximity to various input ports (eg sensory nerves) output ports (eg motor nerves), and other brain areas.

(this would also explain why the brain has a pretty consistent area dedicated to reading/writing, even though we haven’t been literate long enough to evolve new literacy-related structures)

Deep learning agents are also a poorly-differentiated mass of neurons. As they get inputs and outputs (ie training data) they slowly “evolve”/develop the ability to “recognize” patterns. We don’t know how they do this or what recognition-abilities they’re evolving, except by speculating (the way Marcus and I are doing) based on what kinds of problems they can and can’t solve.

It would make sense to me if poorly-differentiated blobs of neurons, when having lots of problems thrown at them, gradually move from developing simpler pattern-recognition programs (eg edge detectors), to more complicated pattern-recognition programs, all the way up to world-modeling, without any of these being hard-coded into the territory.

(the brain does have a lot of things hard-coded - ie we’re not blank slates - but its plasticity suggests that the forms of hard-coding we’re talking about here are helpful but not completely necessary for cognition)

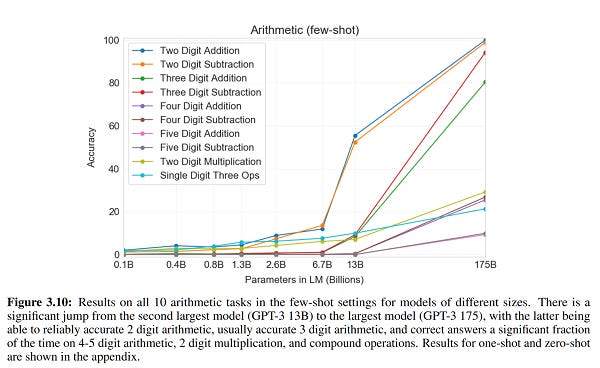

If this were true, it would mean that as a blob of neurons got bigger, more sophisticated, and saw more training data, it would eventually develop new capabilities that weren’t hard-coded in, and that smaller versions of the same blob didn’t have. One of the really exciting things about GPT-3 was its sudden and unplanned development of new capabilities over GPT-2 (its creators mention “translation, question-answering, and cloze tasks, as well as several tasks that require on-the-fly reasoning or domain adaptation, such as unscrambling words, using a novel word in a sentence, or performing 3-digit arithmetic”).

This seems like a good fit for the chimp → human transition, where evolutionary lineages that couldn’t do a bunch of difficult things for the first few hundred million years suddenly became good at those things in an evolutionary eyeblink. The ~5 million chimp/human gap seems like enough time to scale up chimp brains a bit (which definitely happened), but not enough time to invent a fundamentally new architecture. It wouldn’t surprise me if the architecture changed a little during this time, but we’re limited in how fundamental a change we can talk about over that period.

I’m not at all sure this is true! I’m honestly close to 50-50 here. Maybe the PFC actually is magic! It just confuses me that Marcus seems to think we’ve ruled out the theory that this kind of scaling is possible, when I feel like we’ve heard plausible arguments on both sides. Nothing we’ve seen in GPTs or any other AI thus far disproves the scaling hypothesis, and a lot of what we’ve seen supports it.

So sure, point out that large language models suck at reasoning today. I just don’t see how you can be so sure that they’re still going to suck tomorrow. Lemurs sucked for millions of years, then scaled up a bit and took over the world!

V.

…is one possible argument.

Another possible argument is: language models and other deep learners really aren’t doing the same thing humans do - but whatever, their thing is powerful/effective/dangerous too.

Suppose that GPT-X took over the world and killed all humans. Millennia later, some alien archaeologists come and investigate. They conclude that since its training data included Alexander the Great and Caesar, it was just pattern-matching to the kind of things they did (multiplied by a vector representing the difference between ancient and modern times), and GPT-X never demonstrated any true intelligence. So . . . what?

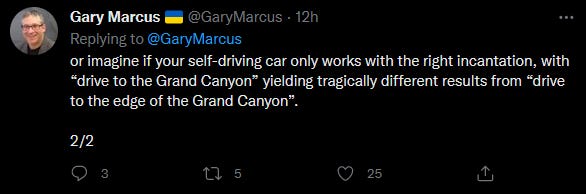

I imagine this situation ALL THE TIME and I hate it. I think the impetus behind a lot of the AI risk stuff is that we’re barrelling to a world where AIs have far more than self-driving-car levels of capabilities, while being unpredictable in ways that are a lot like this.

I imagine this situation ALL THE TIME and I hate it. I think the impetus behind a lot of the AI risk stuff is that we’re barrelling to a world where AIs have far more than self-driving-car levels of capabilities, while being unpredictable in ways that are a lot like this.

The history of the past few decades has been people getting surprised, again and again, at how much AIs can do without being “generally intelligent”. Douglas Hofstadter predicted in 1979 that any AI that could beat a grandmaster at chess would also be able to decide chess was boring and it preferred writing poetry. Instead, we got Deep Blue, so domain-specific it can’t even do so much as play checkers.

Worse, now we have AIs that can switch between writing poetry and playing chess, and it still seems like a clever parlor trick rather than anything like real intelligence. I think basically nobody predicted this: narrow AI has won victories beyond past generations’ imagination.

(cf. Nostalgebraist’s Human Psycholinguists: A Critical Appraisal)

So even if GPTs aren’t a step on the path towards some sort of human-like AGI thing, I have no idea where they’ll end up. Replacing humans at all jobs? Writing novels? Taking over the world? If this seems crazy to you, “solve protein folding” sounded crazy ten years ago, and they already did that! At this point I will basically believe anything.

VI.

So I’m not going to take Marcus’ bet that GPT-4 will be perfect (as if anything ever is!). But here are some things I do believe, with confidence levels:

-

At some point before 2030, someone will come out with a deep-learning-based language model which is significantly better than the current state of the art, by Gary Marcus’ admission (97%)

-

At some point before 2030, someone will come out with a DLBLM which makes few or no embarrassing errors on practical reasoning problems - for example, maybe it can beat a 10 year old child on this genre of question. (66%)

-

When we finally get something that most people agree is AGI, whether by Marcus’ definition here or just by common sense, it will be a descendant in some important way of the kind of deep learning that produced GPT-3. (90%)

-

…as above, and also it won’t incorporate a further paradigm shift centering around deliberate human addition of the kind of neurosymbolic systems Marcus talks about (it can still include other paradigm shifts) (66%)

-

…in fact, it won’t incorporate any further paradigm shifts at all, beyond the bare minimum required to let it do things other than handle short text strings (eg actuators, sensors, larger attention windows, etc) - its brain won’t be that much more different from current AIs than current AIs are from 2015 AIs. (40%)