The Phrase "No Evidence" Is A Red Flag For Bad Science Communication

Related to: Doctor, There Are Two Types Of No Evidence; A Failure, But Not Of Prediction.

I.

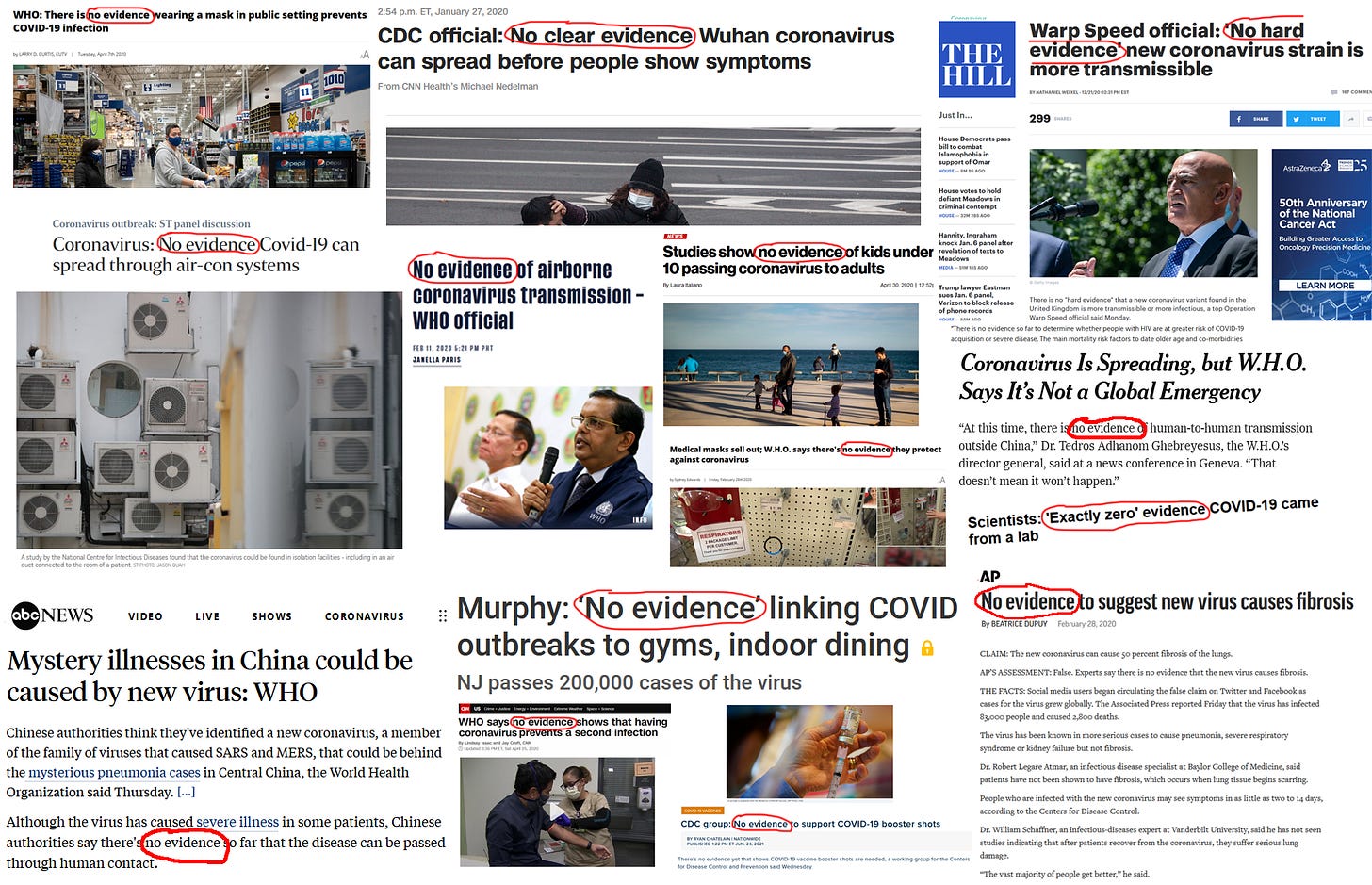

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Every single one of these statements that had “no evidence” is currently considered true or at least pretty plausible.

In an extremely nitpicky sense, these headlines are accurate. Officials were simply describing the then-current state of knowledge. In medicine, anecdotes or hunches aren’t considered “real” evidence. So if there hasn’t been a study showing something, then there’s “no evidence”. In early 2020, there hadn’t yet been a study proving that COVID could be airborne, so there was “no evidence” for it.

On the other hand, here is a recent headline: No Evidence That 45,000 People Died Of Vaccine-Related Complications. Here’s another: No Evidence Vaccines Cause Miscarriage. I don’t think the scientists and journalists involved in these stories meant to shrug and say that no study has ever been done so we can’t be sure either way. I think they meant to express strong confidence these things are false.

You can see the problem. Science communicators are using the same term - “no evidence” - to mean:

-

This thing is super plausible, and honestly very likely true, but we haven’t checked yet, so we can’t be sure.

-

We have hard-and-fast evidence that this is false, stop repeating this easily debunked lie.

This is utterly corrosive to anybody trusting science journalism.

Imagine you are John Q. Public. You read “no evidence of human-to-human transmission of coronavirus”, and then a month later it turns out such transmission is common. You read “no evidence linking COVID to indoor dining”, and a month later your governor has to shut down indoor dining because of all the COVID it causes. You read “no hard evidence new COVID strain is more transmissible”, and a month later everything is in panic mode because it was more transmissible after all. And then you read “no evidence that 45,000 people died of vaccine-related complications”. Doesn’t sound very reassuring, does it?

II.

Unfortunately, I don’t think this is just a matter of scientists and journalists using the wrong words sometimes. I think they are fundamentally confused about this.

In traditional science, you start with a “null hypothesis” along the lines of “this thing doesn’t happen and nothing about it is interesting”. Then you do your study, and if it gets surprising results, you might end up “rejecting the null hypothesis” and concluding that the interesting thing is true; otherwise, you have “no evidence” for anything except the null.

This is a perfectly fine statistical hack, but it doesn’t work in real life. In real life, there is no such thing as a state of “no evidence” and it’s impossible to even give the phrase a consistent meaning. EG:

Is there “no evidence” that using a parachute helps prevent injuries when jumping out of planes? This was the conclusion of a cute paper in the BMJ , which pointed out that as far as they could tell, nobody had ever done a study proving parachutes helped. Their point was that “evidence” isn’t the same thing as “peer-reviewed journal articles”. So maybe we should stop demanding journal articles, and accept informal evidence as valid?

Is there “no evidence” for alien abductions? There are hundreds of people who say they’ve been abducted by aliens! By legal standards, hundreds of eyewitnesses is great evidence! If a hundred people say that Bob stabbed them, Bob is a serial stabber - or, even if you thought all hundred witnesses were lying, you certainly wouldn’t say the prosecution had “no evidence”! When we say “no evidence” here, we mean “no really strong evidence from scientists, worthy of a peer-reviewed journal article”. But this is the opposite problem as with the parachutes - here we should stop accepting informal evidence, and demand more scientific rigor.

Is there “no evidence” homeopathy works? No, here’s a peer-reviewed study showing that it does. Don’t like it? I have eighty-nine more peer-reviewed studies showing that right here. But a strong theoretical understanding of how water, chemicals, immunology, etc operate suggests homeopathy can’t possibly work, so I assume all those pro-homeopathy studies are methodologically flawed and useless, the same way somewhere between 16% and 89% of other medical studies are flawed and useless. Here we should reject journal articles because they disagree with informal evidence!

Is there “no evidence” that King Henry VIII had a spleen? Certainly nobody has published a peer-reviewed article weighing in on the matter. And probably nobody ever dissected him, or gave him an abdominal exam, or collected any informal evidence. Empirically, this issue is just a complete blank, an empty void in our map of the world. Here we should ignore the absence of journal articles and the absence of informal evidence, and just assume it’s true because obviously it’s true.

I challenge anyone to come up with a definition of “no evidence” that wouldn’t be misleading in at least one of the above examples. If you can’t do it, I think that’s because the folk concept of “no evidence” doesn’t match how real truth-seeking works. Real truth-seeking is Bayesian. You start with a prior for how unlikely something is. Then you update the prior as you gather evidence. If you gather a lot of strong evidence, maybe you update the prior to somewhere very far away from where you started, like that some really implausible thing is nevertheless true. Or that some dogma you held unquestioningly is in fact false. If you gather only a little evidence, you mostly stay where you started.

I’m not saying this process is easy or even that I’m very good at it. I’m just saying that once you understand the process, it no longer makes sense to say “no evidence” as a synonym for “false”.

III.

Okay, but then what? “No Evidence That Snake Oil Works” is the bread and butter of science journalism. How do you express that concept without falling into the “no evidence” trap?

I think you have to go back to the basics of journalism: what story are you trying to cover?

If the story is that nobody has ever investigated snake oil, and you have no strong opinion on it, and for some reason that’s newsworthy, use the words “either way”: “No Evidence Either Way About Whether Snake Oil Works”.

If the story is that all the world’s top doctors and scientists believe snake oil doesn’t work, then say so. “Scientists: Snake Oil Doesn’t Work”. This doesn’t have the same faux objectivity as “No Evidence Snake Oil Works”. It centers the belief in fallible scientists, as opposed to the much more convincing claim that there is literally not a single piece of evidence anywhere in the world that anyone could use in favor of snake oil. Maybe it would sound less authoritative. Breaking an addiction to false certainty is as hard as breaking any other addiction. But the first step is admitting you have a problem.

But I think the most virtuous way to write this is to actually investigate. If it’s worth writing a story about why there’s no evidence for something, probably it’s because some people believe there is evidence. What evidence do they believe in? Why is it wrong? How do you know?

Some people thought masks helped slow the spread of COVID. You can type out “no evidence” and hit “send tweet”. But what if you try to engage the argument? Why do people believe masks could slow spread? Well, because it seems intuitively obvious that if something is spread by droplets shooting out of your mouth, preventing droplets from shooting out of your mouth would slow the spread. Does that seem like basically sound logic? If so, are you sure your job as a science communicator requires you to tell people not to believe that? How do you know they’re not smarter than you are? There’s no evidence that they aren’t!