Unpredictable Reward, Predictable Happiness

[Epistemic status: very conjectural. I am not a neuroscientist and they should feel free to tell me if any of this is totally wrong.]

I.

Seen on the subreddit: You Seek Serotonin, But Dopamine Can’t Deliver. Commenters correctly ripped apart its neuroscience; for one thing, there’s no evidence people actually “seek serotonin”, or that serotonin is involved in good mood at all. Sure, it seems to have some antidepressant effects, but these are weak and probably far downstream; even though SSRIs increase serotonin within hours, they take weeks to improve mood. Maxing out serotonin levels mostly seems to cause a blunted state where patients can’t feel anything at all.

In contrast, the popular conception of dopamine isn’t that far off. It does seem to play some kind of role in drive/reinforcement/craving, although it also does many, many other things. And something like the article’s point - going after dopamine is easy but ultimately unsatisfying - is something I’ve been thinking about a lot.

Any neuroscience article will tell you that the “reward center” of the brain - the nucleus accumbens - monitors actual reward minus predicted reward. Or to be even more finicky, currently predicted reward minus previously predicted reward. Imagine that on January 1, you hear that you won $1 billion in the lottery. It’s a reputable lottery, they’re definitely not joking, and they always pay up. They tell you that it’ll take a month for them to get the money in your account, and you should expect it February 1. You’re going to be really busy the whole month of February, so you decide not to start spending until March 1. What happens?

My guess is: January 1, when you first hear you won, is the best day of your life. February 1, when the money arrives in your account, is nice but not anywhere near as good. March 1, when you start spending the money, is pretty great because you go do lots of fun things.

However good you predicted your life would be last year, you make a big update January 1 when you hear you won the lottery. Nothing good has happened yet: you don’t have money and you’re not buying fancy things. But your predictions about your future levels of those things shoot way up, which corresponds to happiness and excitement. In contrast, on February 1 you have $1 billion more than on January 31, but because you predicted it would happen, it’s not that big a mood boost.

What about March 1? Suppose you do a few specific things - you buy a Ferrari, drive it around, and eat dinner in the fanciest restaurant in town. Do you enjoy these things? Presumably yes. Why? You knew all throughout February that you were planning to get a Ferrari and a fancy dinner today. And you knew that Ferraris and fancy dinners were pleasant; otherwise you wouldn’t have gotten them. So how come predicting you would get the money mostly cancels out the goodness of getting the money, but predicting you would get the Ferrari/dinner doesn’t cancel out the goodness of the Ferrari/dinner?

Or: suppose that every year I ate cake on my birthday. This is very predictable. But I would expect to still enjoy the cake. Why?

It seems like maybe there are two types of happiness: happiness that is cancelled out by predictability, and happiness that isn’t.

Happiness that’s cancelled out by predictability sounds like our old friend the hedonic treadmill: if your life gets better, that doesn’t improve your long-term happiness, because you just adjust. Something like this must be sort of true - if medieval serfs had normal happiness level, modern middle-class people have so many advantages over them that you’d expect them to be delighted all the time, but this doesn’t seem right . On the other hand, the hedonic treadmill can’t be the whole story, or else there would be no advantage of being rich/healthy/popular to being poor/sick/shunned. But studies usually find that rich people tend to be happier than poor people.

This post is about searching for those two different kinds of happiness.

II.

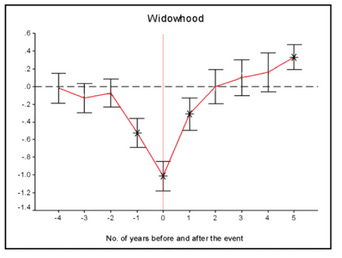

I once attended a presentation on grief at a psychiatry conference. The presenter treated grief as a form of updating on prediction error. Your spouse dies. The next morning, you wake up and expect to find your spouse in bed with you. They aren’t. The situation is worse than you expected. Actual hedonic state is lower than predicted hedonic state, reward prediction error is negative. You now feel bad.

Of course, your conscious brain should be able to fully update on “I will not see my spouse again” the moment they die. This explanation assumes that the unconscious is slower to update. I accept this assumption. I’ve never had a partner die, but I’ve had some bad breakups. The next few months really are a series of “If only X were here…” and “This is so much worse without X”. Then eventually I mostly update and stop thinking of X being around as a natural comparison. The depressing part of the breakup is over. I assume something like this happens with bereavement, which is usually considered to be especially bad for a few months to a few years.

Self-reported life satisfaction before, during, and after the year where a spouse dies. Source is here, This graph is for women; you can find men at the link.

Self-reported life satisfaction before, during, and after the year where a spouse dies. Source is here, This graph is for women; you can find men at the link.

This isn’t to say people eventually fully recover from a spouse’s death (although according to the chart, their life satisfaction does). I would expect the effect in isolation to be asymptotic, where after long enough it becomes lower than whatever threshold you’re asking about. I can’t provide evidence for this other than subjective impression.

Here it seems like there’s an extra kind of sadness associated with prediction error. It takes a few months or years to fully update predictions, and then you just have a normal stable sadness.

III.

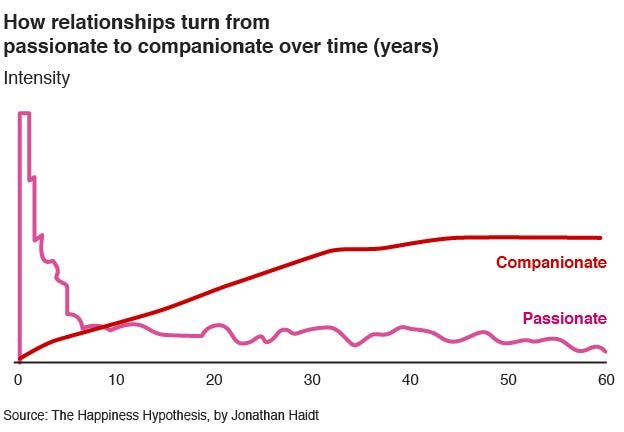

My old psych 101 textbook said that romantic love lasts between a few months and a few years. Jonathan Haidt apparently has this graph in his book Happiness Hypothesis , though I don’t have the book and can’t evaluate the source:

Some more modern studies have challenged this; as far as I can tell they are nitpicking different types of love. Every study agrees there is a quick-burning type of love that lasts a few months to a few years, and a slow-burning one that hopefully grows over time.

Although I don’t always trust psych studies, my experiences with the polyamory community strongly confirm this. Poly people talk about “new relationship energy” - if you start a relationship with a new person, you will be passionately into them for a few months, usually at the expense of all your other relationships, before settling back down again. Most poly advice books will give you tips for managing it, which mostly boil down to for God’s sake, don’t take your feelings seriously and deprioritize all your other relationships because this new one is so much better.

New relationship energy seems like a good match for bereavement. Both last a few months to a few years. Both seem to involve updating on your life taking a surprising turn. Until you’ve fully updated, you feel unusually good/bad. After that…

…I know many people who have been married for decades and still have great relationships. The typical retort is that they are doing something called “companionate love” which is totally different. But I know some people who have been married for decades and still have great sex (sometimes even with each other!)

This sort of tracks with Part I and II. There seems to be an extra-sparkly type of happiness associated with new relationships (relationships you haven’t adjusted to yet, that aren’t baked into your predictions, that haven’t already been hedonic-treadmilled away). This lasts a few months or years while you slowly update your predictions. Then hopefully you end up with a more stable type of happiness associated with good long-term relationships.

IV.

Here’s some advice for aspiring psychiatrists: never tell your patient “yeah, seems like you’re cursed to be perpetually unhappy”.

The closest I’ve ever come to violating that advice was with a patient who came in for trouble with (I’m randomizing their gender; it landed on male) his girlfriend.

He described his girlfriend in a way that made it clear she was abusive, emotionally manipulative, and had a bunch of completely-untreated psychiatric issues. He was well aware of all of this. He had tried breaking up with her a few times. Each time, all of his own issues went away, and his life was great. Then, each time, he got back together with her. So we did some therapy together for a while, tried to figure out why, and all I could ever get out of him was that she was more “exciting”. It was something about knowing that on any given day, she might either adore him or try to kill him. With every other partner he’d tried, it was either one or the other. With her it was some kind of perverse exactly-50-50 probability, and he was addicted to it.

I’m disappointed the gender randomization landed on male here; we usually associate “person who keeps dating abusive partner after abusive partner for incomprehensible reasons” with women. This pattern has always confused me, and I never know what advice to give people who find themselves falling into it.

I thought about this recently when watching a great couple who loved each other very much. The wife said some kind of extremely mushy compliment to the husband about how much she loved him, and the husband joked something like “Oh, you always say that.” He maybe mildly appreciated the compliment, but they really were always saying incredibly nice things about how much they appreciated each other, to the point where it kind of started to sound kind of like background noise.

Suppose you reached the point where it sounded exactly like background noise. Your spouse could give you a dozen red roses and a sonnet about your many excellent qualities every day, and it wouldn’t update you at all. At that point, you either need to have the mysterious “companionate love” thing in place - something that isn’t based on reward prediction error - or you are doomed to never feel another positive emotion from your relationship at all.

What if for some reason you can’t do companionate love? I wonder if you would end up like my patient - addicted to someone who had a 50-50 chance of being adoring or terrible at any given time, just because half the time you get positive prediction error out of it, and you’re able to feel anything at all. Of course, half the time you get negative prediction error. But as gambling addictions show, the positive and negative errors don’t necessarily have to add up above 0 in order for something to be compelling. Everyone has some weird function that doesn’t correspond to normal addition, and maybe for some people dating a person who gives good vs. bad signals exactly 50% of the time is the only way to get that function in the black.

This also reminds me of the bane of relationship counselors everywhere: the wife (yes, it’s usually the wife) who complains that the husband never gets her flowers. Then the husband gets her flowers, and the wife says “it doesn’t count, you should have known without me telling you”. To this couple, gestures of affection are meaningless unless unpredictable. If the husband had gotten the wife flowers before she had asked, she would have been delighted. If he’d tried the same thing a second time, it wouldn’t have counted; she would have already predicted it and factored it in.

V.

Some more serious psychiatry advice: when patients start taking stimulants (eg Adderall) daily, a common pattern is that they feel euphoric and on-top-of-the-world for a few days to a week. After that, the euphoria will go away, and the stimulant will just do its normal job of helping them focus. Sometimes, additionally, after a few months or years, they’ll gain complete tolerance to the stimulant, and it won’t help them focus anymore. It seems to be a minority of people who get this complete tolerance, and usually a short break (a few weeks to months) can reset it and make the stimulant work again. Sometimes a very long break (months to years) can reset the euphoria, and they can feel on top of the world for a few days again after restarting it. But there’s no way to get the euphoria for more than a few days per months-to-years, sorry.

How similar is the euphoria → focus → nothing pattern to the passionate love → companionate love → nothing pattern, and the grief → lingering unhappiness → nothing pattern? Are the unlucky people who gain quick tolerance to stimulants analogous to the unlucky people who can’t enjoy normal relationships and have affairs or emotionally manipulative partners? Would they be the same people? I don’t know of any research on this (though I would expect them not to be literally the same people; different people seem to have addictions to different drugs and behaviors).

VI.

I recently read TurnTrout’s Reward Is Not The Optimization Target on Less Wrong. It’s technically about AI, but half the useful things I’ve learned about psychology recently have started out being about AI, so let’s not hold that against it.

It points out that AIs are not, technically, “trying to get reward”. You can prove this is true because (as far as I know), most modern AIs only get reward during training. Then you deploy them and they keep doing stuff, even though there is no way to get reward in the deployment environment. It’s fair to describe this as “doing things like the things that got them reward in the past”, but not as reward-seeking.

This is an important distinction! One big concern in AI alignment is that AIs will learn to hack their own reward systems (ie wirehead), and devote their energy to implementing such hacks (which produce super-high reward) instead of doing their assigned tasks (which only produce normal levels of reward). TurnTrout argues this won’t happen, at least for the current paradigm of AIs. If they didn’t learn to hack their reward system in training, they’re not going to want to do it in deployment, even if they are smart enough to know that it would work.

This makes sense to me from a human perspective. I know there are ways to hack my reward system - eg heroin and electrodes wired directly into the reward center of my brain. I know that if I used them, I would feel really rewarded. But I have no desire to use them. In fact, I’m pretty against using them. They would prevent me from doing all the things I like - ie the things that have rewarded me in the past.

What would it mean if reward wasn’t my optimization target? One way I imagine this is eg the alcoholic who drinks compulsively but doesn’t really enjoy it any longer. At some point in the past, drinking gave positive reward. Now that reward has all been predicted away, but the behavior remains. If drinking ever stopped being reinforcing (eg the bar owner secretly substituted non-alcoholic beer), then there would be negative prediction error and the behavior would eventually stop. But as it is, the system is stable: the alcoholic drinks, it’s exactly as good as predicted, and he will keep drinking at the same rate.

(is this just the Sinclair Method? Then how come drinking on the Sinclair Method is usually neutral rather than aversive, given that the drinker must be getting less reward than predicted? Is it because we’re blocking opioids rather than dopamine? Why are we doing that?)

I think the main thing I get from this article is a renewed determination to think of reward as “that thing which changes behavioral programs” rather than as some sort of fuzzy concept of “the target” or “good things that I like”. This softens the blow of the original question - eating cake on my birthday might not produce behavior change, but it might still be enjoyable.

VII.

All of these examples are meant to point to a similar phenomenon: an extra kind of happiness that persists only in the context of prediction error, and eventually goes away, plus a lingering kind of happiness which can be enjoyed even after prediction error has been corrected. What explains this pattern?

I disagreed with the serotonin-focused explanation at the beginning of the post, but you can rescue it to be about dopamine vs. some other neurotransmitter (endogenous opioids are a popular choice). This would correspond nicely to the liking vs. wanting theory, even though technically they’re explaining different things (pleasure + motivation, vs. two different kinds of pleasure).

This review of dopamine reward signaling admits that there are two “components of phasic dopamine response”; one gets cancelled out by predicted reward, the other doesn’t. This seems suspicious, but they insist that the non-cancelled one is just a “detection signal” and not involved in things actually being rewarding.

Another possibility is to say you can never predict away all reward - sort of like how even after your spouse has been dead for weeks, your brain still hasn’t fully adjusted its “predictions”. This would also match an “active inference” theory of drives, where the body implements hunger by something like a non-update-able prediction that you’re well-fed, and then lets you be unhappy about the “prediction error” and work to fix it. Maybe some lingering happiness from things like good relationships come from an inability to update the last little bit of the “I am not in a good relationship” prediction, added specifically as a hack so that people in good relationships can still be happy. But I don’t think this matches the neuroscientific evidence; you can just check the reward center for simple things (traditionally a monkey drinking juice) and find that it’s fully adjusted away this prediction (even though the monkey presumably enjoys the juice just as much as we enjoy our predicted rewards like Ferraris.)

I got a chance to talk to Andres from Qualia Research about this. He emphasized (sorry if I am mistransmitting any of this) his belief that happiness is related to something like consonance of brain states (which I think sort of relates to low free energy / low prediction error). The reward center works because it’s an interchange between many brain regions, and when activated it connects them and globally increases consonance in the brain. But you can also increase consonance other ways, and predictability won’t cancel these out.

So I would amend the original post on the subreddit to “You seek unpredicted reward, but by definition you can never get this consistently; luckily predicted reward can be pretty good too.” I still don’t feel like I understand exactly how this is implemented.

[image creditthis video]