Updated Look At Long-Term AI Risks

The last couple of posts here talked about long-term risks from AI, so I thought I’d highlight the results of a new expert survey on exactly what they are. There have been a lot of these surveys recently, but this one is a little different.

Starting from the beginning: in 2012-2014, Muller and Bostrom surveyed 550 people with various levels of claim to the title “AI expert” on the future of AI. People in philosophy of AI or other very speculative fields gave numbers around 20% chance of AI causing an “existential catastrophe” (eg human extinction); people in normal technical AI research gave numbers around 7%. In 2016-2017, Grace et al surveyed 1634 experts, 5% of whom predicted an extremely catastrophic outcome. Both of these surveys were vulnerable to response bias (eg the least speculative-minded people might think the whole issue was stupid and not even return the survey).

The new paper - Carlier, Clarke, and Schuett (not currently public, sorry, but you can read the summary here) - isn’t exactly continuing in this tradition. Instead of surveying all AI experts, it surveys people who work in “AI safety and governance”, ie people who are already concerned with AI being potentially dangerous, and who have dedicated their careers to addressing this. As such, they were more concerned on average than the people in previous surveys, and gave a median ~10% chance of AI-related catastrophe (~5% in the next 50 years, rising to ~25% if we don’t make a directed effort to prevent it; means were a bit higher than medians). Individual experts’ probability estimates ranged from 0.1% to 100% (this is how you know you’re doing good futurology).

None of that is really surprising. What’s new here is that they surveyed the experts on various ways AI could go wrong, to see which ones the experts were most concerned about. Going through each of them in a little more detail:

1. Superintelligence: This is the “classic” scenario that started the field, ably described by people like Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky. AI progress goes from human-level to vastly-above-human-level very quickly, maybe because slightly-above-human-level AIs themselves are speeding it along, or maybe because it turns out that if you can make an IQ 100 AI for $10,000 worth of compute, you can make an IQ 500 AI for $50,000. You end up with one (or a few) completely unexpected superintelligent AIs, which wield far-future technology and use it in unpredictable ways based on untested goal structures.

2. Influence-seeking ends in catastrophe: Described by Paul Christiano here. Modern machine learning techniques “evolve” and “select” AIs that appear good at a certain goal. But sufficiently intelligent AIs with a wide variety of goals (eg power-seeking) will try to seem good at the goal we want them to do, since that’s the best way to be kept online and put in control of important resources, which will help them achieve their real goals. Depending on how we design AI goal structures, some large percent of the AIs we use at any given time might have unexpected goals (including pure power-seeking). As long as everything stays stable, that’s fine; it will continue to be in the AIs’ best interests to play along. But if something unusual happens, especially something that limits our attempts to control AIs, it might cause many AIs at once to switch to their real goal, whatever that is (or one very important AI, like one that controls nuclear weapons).

3. Goodharting ourselves to death: Described by Paul Christiano here. There are some things that are easy to measure as a number, like how many votes a candidate gets, how much profit a company is making, or how many crimes are reported to police. There are other things that are hard or impossible, like how good a candidate is, how much value a company is providing, or how many crimes happen. We try to use the former as proxies for the latter, and in normal human society this works sort of okay. But it’s much easier to train/optimize AIs to increase measurable proxy numbers than real values. So AIs would be incentivized to find ways to improve proxies (easy) without necessarily finding ways to satisfy our real values (hard) - for example, a real Robocop, programmed to “reduce the crime rate”, might try to make it as hard as possible for people to report crimes - and then try to deceive everyone involved so they don’t close this loophole in a way that makes the (measured) crime rate increase. As AIs take over more and more of society, we end up in the position of the mythical king whose kingdom is falling apart around him, but who does nothing because flattering courtiers keep telling him everything is okay.

4. Some kind of AI-related war: Described by Allan Dafoe here. Not a war against AI, but a war between normal human countries that happens because of AI for some reason. Maybe AI turns out to be really militarily valuable, and whichever country gets it first decides to push its advantage before others catch up. Maybe other countries predict that will happen and launch a pre-emptive strike. Maybe AI is able to undermine nuclear deterrence somehow.

5. Bad actors use AI to do something bad: Maybe smarter-than-human AIs are able to invent really good superweapons, or bioweapons, and terrorists use them to destroy the world. Maybe some dictatorship (cough China cough) figures out how to use AI to predict, monitor, and crush dissent at a superhuman level, entrenching itself forever. Maybe billionaires use AI to make lots more money and become a permanent feudal oligarchy in a way which is terrible for everyone else.

6. Something else: Catch-all “other” option.

And the winner is…

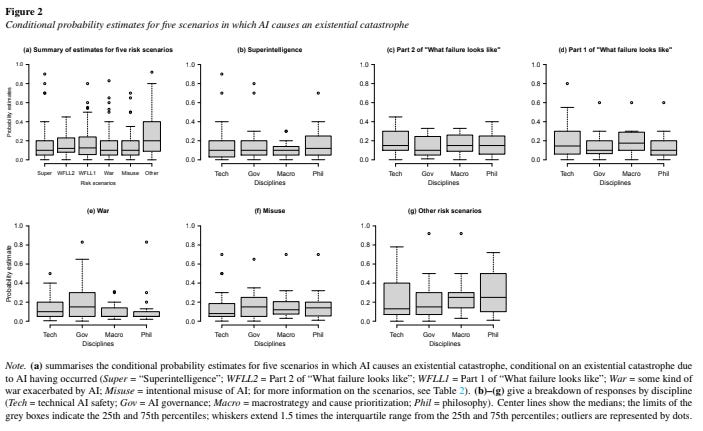

Nobody in particular! All the scenarios got about equal probabilities, except “other”, which was higher.

There was a slight tendency for people to be more concerned about the scenarios relating to the field they were personally in; people working in government/policy were more concerned about wars and misuse, and people working in tech were more concerned about failing to solve hard optimization problems. It’s hard to read the graphs, but this seems like on the order of 10% vs. 15%, which I guess is relatively a big difference even if it’s small in absolute terms.

I find this pretty surprising. I would have expected that very practical “people do bad stuff with the help of AI or because of AI” scenarios like 4 and 5 would rank higher than speculative futuristic sounding ones like 1 - if only because, even if the speculation is entirely correct, people could kill us by doing bad stuff before we ever reach the part of the future where the weird stuff starts happening. But no, everything is pretty similar.

For me, the interesting takeaways here are:

-

Even people working in the field of aligning AIs mostly assign “low” probability (~10%) that unaligned AI will result in human extinction

-

While some people are still concerned about the superintelligence scenario, concerns have diversified a lot over the past few years

-

People working in the field don’t have a specific unified picture of what will go wrong