What Caused The 2020 Homicide Spike?

In my review of San Fransicko , I mentioned that it was hard to separate the effect of San Francisco’s local policies from the general 2020 spike in homicides, which I attributed to the Black Lives Matter protests and subsequent police pullback.

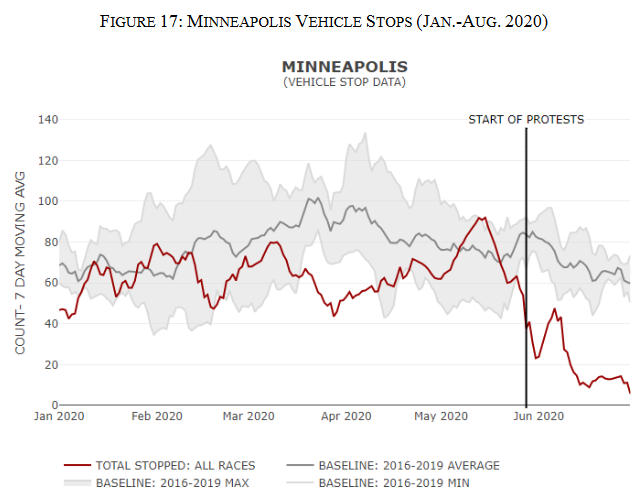

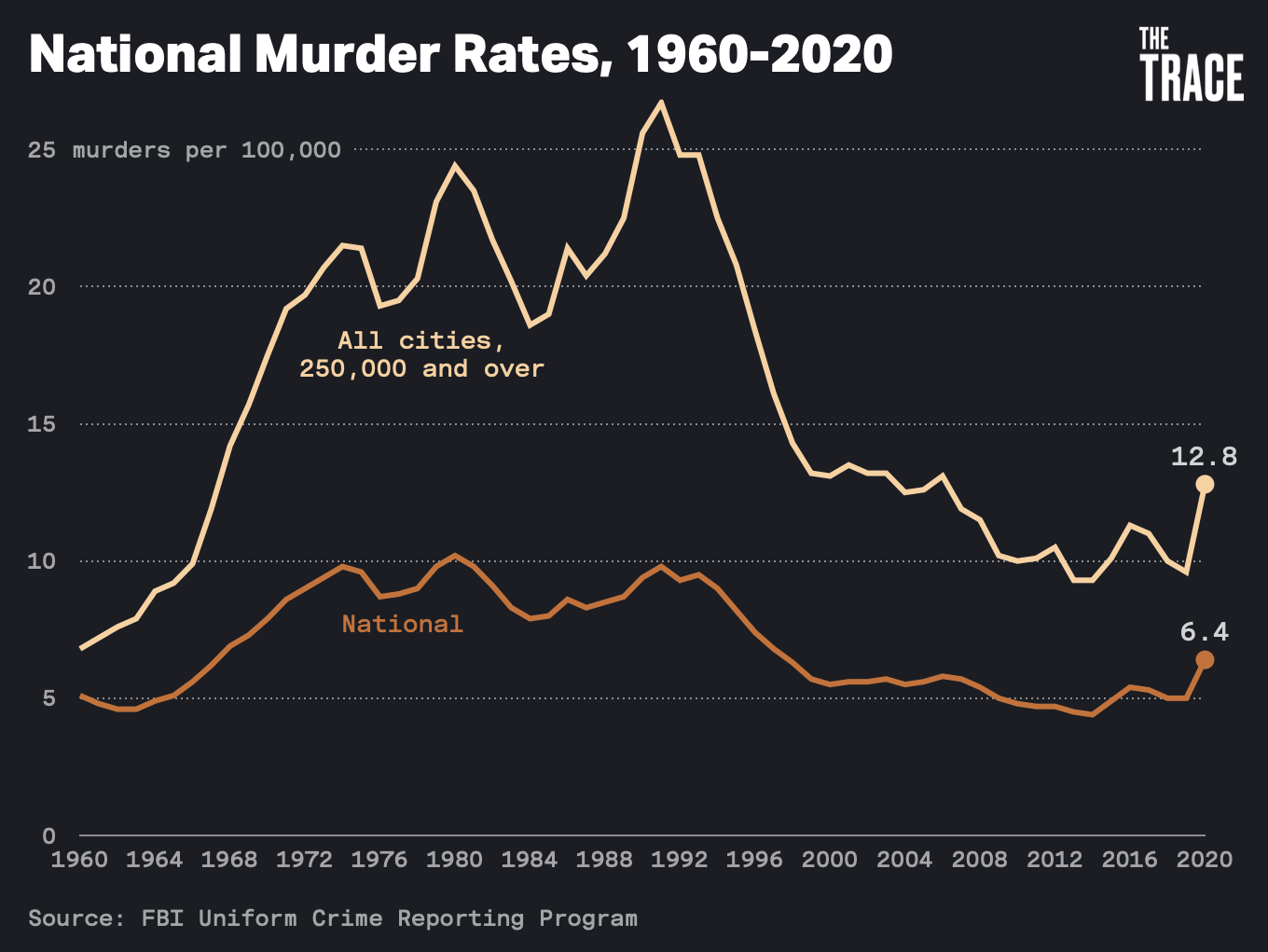

The nationwide 2020 spike in homicides (source). The spike is small compared to the secular trend from the 1960s through 2000, but large by the standards of the past twenty years.

The nationwide 2020 spike in homicides (source). The spike is small compared to the secular trend from the 1960s through 2000, but large by the standards of the past twenty years.

Several people in the comments questioned my attribution, saying that they’d read news articles saying the homicide spike was because of the pandemic, or that nobody knew what was causing the spike. I agree there are many articles like that, but I disagree with them. Here’s why:

Timing

When exactly did the spike start? The nation shut down for the pandemic in mid-March 2020, but the BLM protests didn’t start until after George Floyd’s death in late May 2020. So did the homicide spike start in March, or May?

Let’s check in with the Council on Criminal Justice:

Edited to remove the word “pandemic”, which they put in a place suggesting the red line was associated with the pandemic. They meant the faint graph paper effect was associated with the pandemic. The red line is the BLM protests.

Edited to remove the word “pandemic”, which they put in a place suggesting the red line was associated with the pandemic. They meant the faint graph paper effect was associated with the pandemic. The red line is the BLM protests.

It very clearly started in late May, not mid-March. The months of March, April, and early May had the same number of homicides as usual.

This is the conclusion of most sources I can find. The only dissenter is this Intercept article, which claims the following:

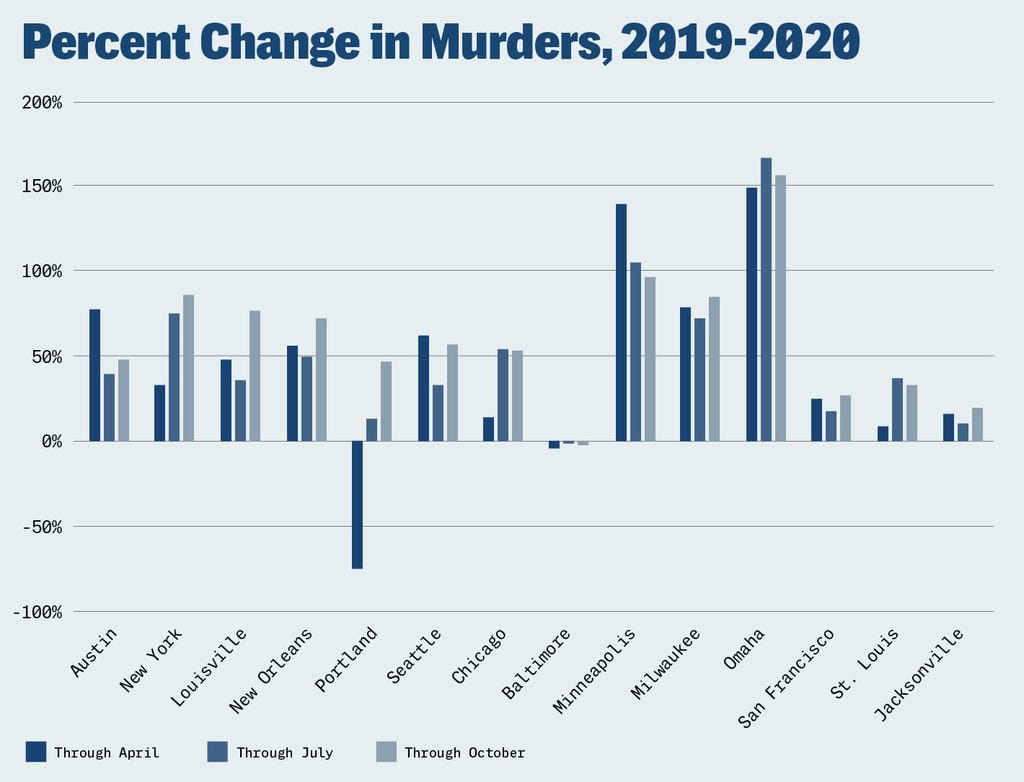

Here it looks like there’s a big change in murders through April, with basically no extra increase through July. This definitely contradicts the graph above. What’s going on here?

I don’t know the Intercept’s criteria for including cities on their chart, but more than half of the cities in the US with the most murders aren’t even on there, whereas they did choose to include such colossi of crime as Omaha, Nebraska. Either they’re cherry-picking on purpose, or using some kind of inscrutable methodology that coincidentally is giving the wrong result.

Of the actually relevant cities on there - New York, Chicago, etc - most of them show the May spike we discussed earlier.

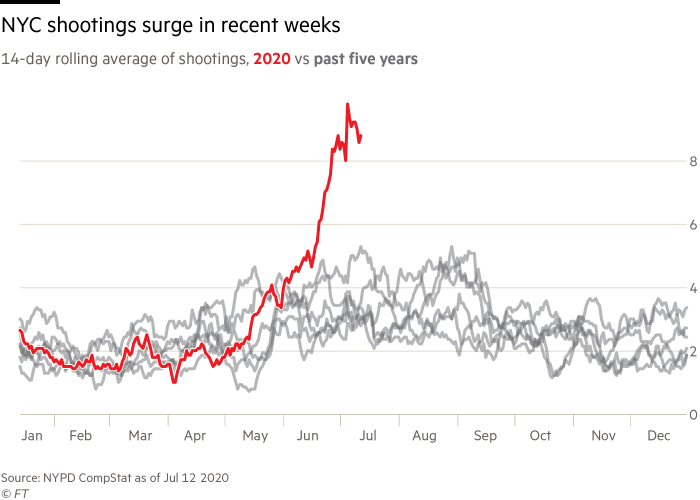

From the Financial Times. Notice no difference from the usual trend in March, April, or early May, then a very obvious spike around the time the BLM protests start on May 25. This is shootings rather than murders, for the same reason discussed below, but murders show a similar though noisier pattern.

From the Financial Times. Notice no difference from the usual trend in March, April, or early May, then a very obvious spike around the time the BLM protests start on May 25. This is shootings rather than murders, for the same reason discussed below, but murders show a similar though noisier pattern.

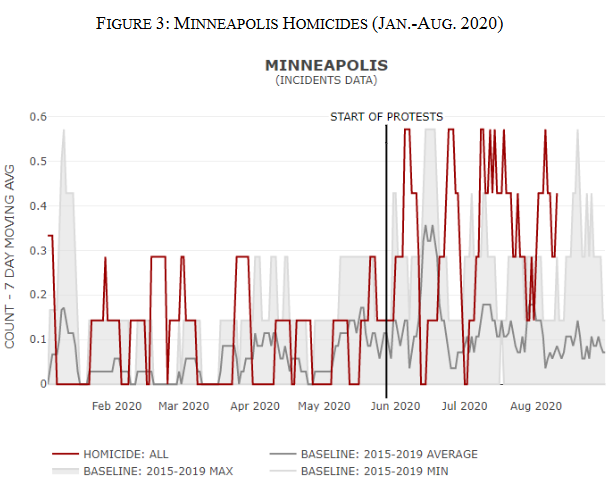

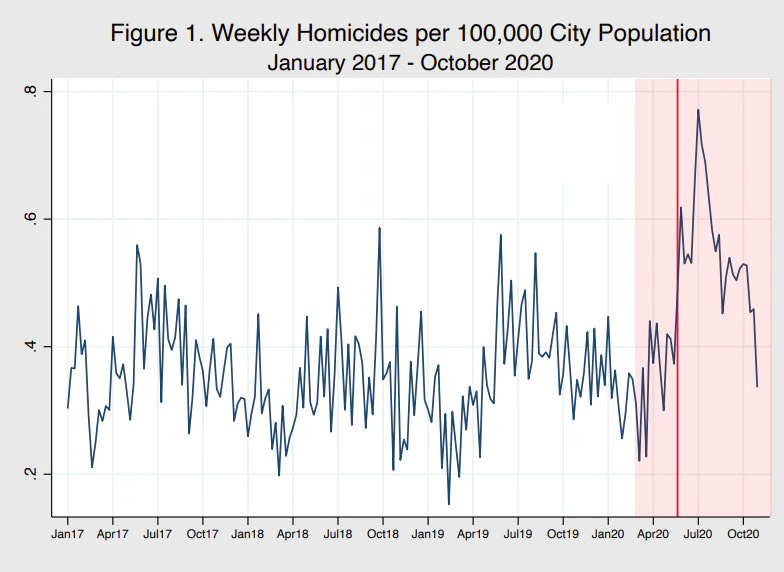

Another surprise on the Intercept’s graph: Minneapolis, the epicenter of BLM protests, saw more of a change in January-April than from May-August. Is this true? Cassell (2020) shows us the data:

It looks like maybe this is random variation; there’s so few murders in Minneapolis in the winter that even one or two looks like a very large percent increase. But the raw data show that the summer was a much bigger deal.

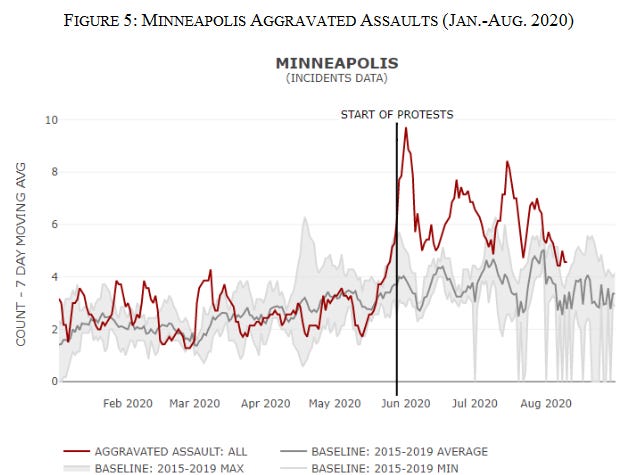

Since murder is very rare, maybe we can get a better view using assault, a crime similar to murder but much more common:

Now the pattern is really obvious, except that it looks like it began about a week before the protests. I’m not sure, but I think this is because the site the paper took this from uses a 7-day rolling average, which smooths the data at the cost of having it be about a week off. A few of the other graphs have this problem as well, but I wouldn’t read too much into it.

Nationwide, the spike in murders clearly happened in May, not March. On a city by city level, it’s hard to tell because murders are so rare. But when we look at other crimes that probably correlate with the murder rate, they clearly go up in May, not March.

Police Pullback

My specific claim is that the protests caused police to do less policing in predominantly black areas. This could be because of any of:

-

Police interpreted the protests as a demand for less policing, and complied.

-

Police felt angry and disrespected after the protests, and decided to police less in order to show everybody how much they needed them.

-

Police worried they would be punished so severely for any fatal mistake that they made during policing that they were less willing to take the risk.

-

The “Defund The Police” movement actually resulted in police being defunded, either of literal funds or political capital, and that made it harder for them to police.

I don’t want to speculate on which of these factors was most decisive, only to say that at least one of them must be true, and that police did in fact pull back. For evidence, see Cassell (2020) again:

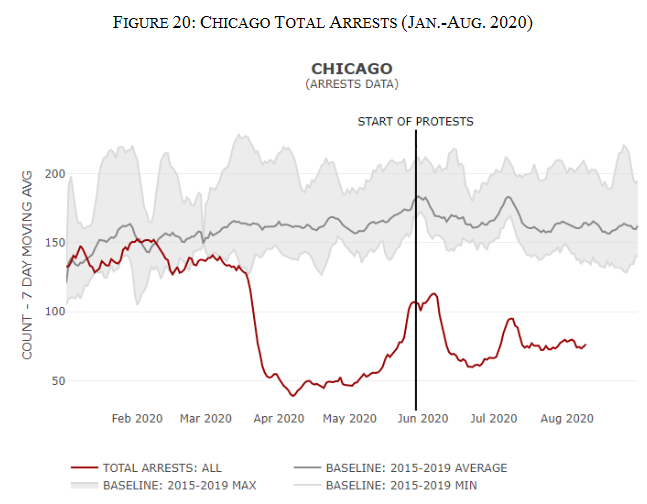

Here’s number of arrests in Chicago. We can see that it goes way down in March when the pandemic starts and everybody (including police and criminals) are indoors, then starts going up again before the protests. Then after the protests it goes back down and stays down. My interpretation is that people complied with the strict lockdown early in the pandemic, that effect was played out by May, and then separately the protests caused a longer-term decrease in policing.

Cassell shows an even more dramatic pattern for traffic stops in Minneapolis:

This itself doesn’t prove that the murder spike was because of the BLM protests rather than the pandemic, since both events caused decreases in policing. But it fleshes out the model and demonstrates a casual chain by which the protests could have caused the spike.

Victims

Who is being targeted in these extra murders?

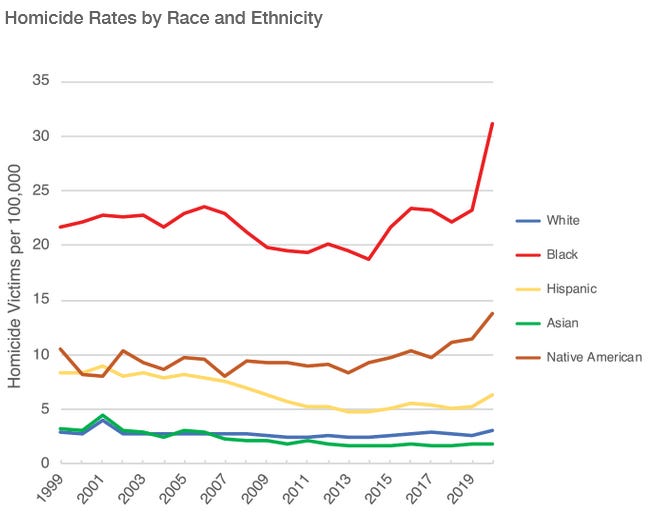

Source: Manhattan Institute. The last number listed on the axis is 2019, but if you click through to the source you’ll see it definitely includes 2020 data.

Source: Manhattan Institute. The last number listed on the axis is 2019, but if you click through to the source you’ll see it definitely includes 2020 data.

The 2020 homicide spike primarily targeted blacks.

(there also seems to be a much smaller spike for Native Americans, but there are so few Natives that I think this might be random, or unrelated).

Most violent crime is within a racial community, and there was no corresponding rise in hate crimes the way I would expect if this was whites targeting blacks, so I think the perpetrators were most likely also black. This was a rise in the level of violence within black communities.

A priori there’s no reason to expect lockdowns and “cabin fever” to hit blacks much harder than every other ethnic group. But there are lots of reasons to expect that the Black Lives Matter protests would cause police to pull back from black communities in particular. I think this is independent evidence that the homicide spike was because of the protests and not the pandemic.

Effects Of Previous Protests

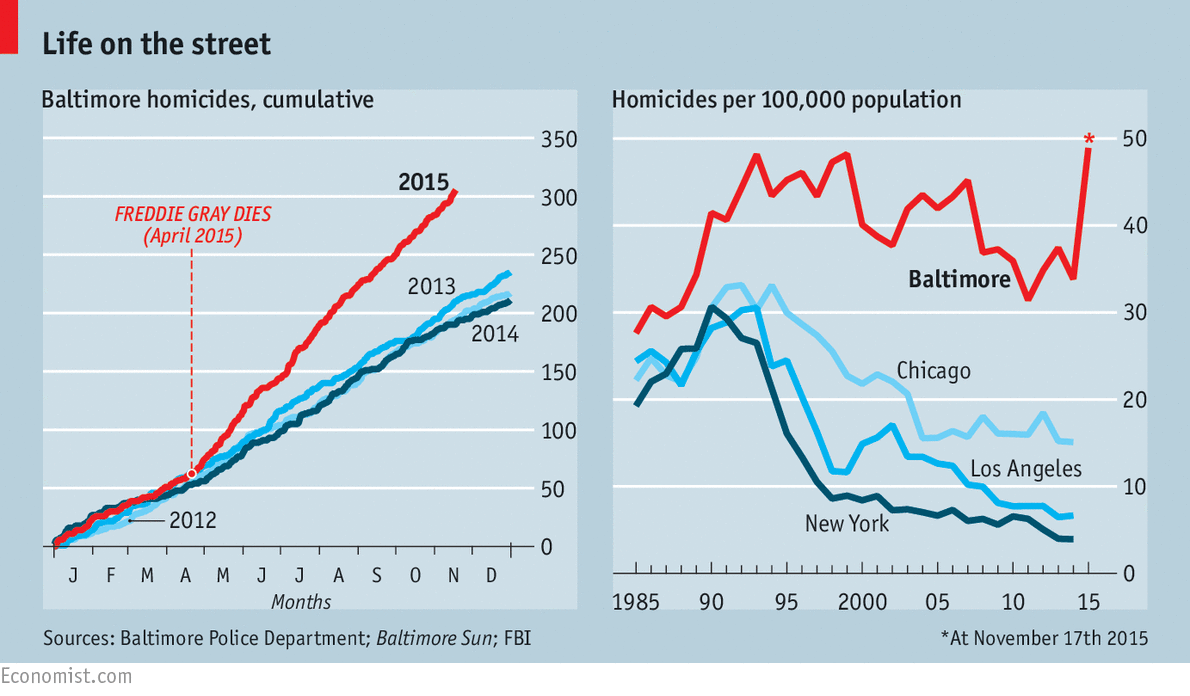

Although the George Floyd protests in May 2020 were the largest round of Black Lives Matters protests, there had been several previous rounds. Most notable were the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO in August 2014, and the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in Baltimore in April 2015. If Black Lives Matters protests can cause homicide spikes, we would expect to see one around this time also.

This was definitely observed by many people, and given the title “Ferguson Effect”. Every official source on the Ferguson Effect is careful to say we can’t be sure it is real / was caused by the protests, just as every source on the recent homicide spike is careful to say the same thing. But let’s look at the evidence:

Source: FactCheck

Source: FactCheck

Here’s a graph of US murder rate until 2018 (ie not showing the most recent spike). You can see a clear spike in 2014.

(You can see the same spike on the graph up to 2021 at the top of this post, it just looks less impressive next to the 2020 spike).

Some detractors point out that this is very small compared to (say) the difference between now and 1990, but all things are smaller than other, larger things, and that doesn’t prevent them from being real or relevant.

Other skeptics point to this study, which claims an overall effect on crime did not occur. The study does claim this, and even says there was no statistically significant break in the homicide trend around 2014. I have no explanation for why their statistics give such a different result than just looking at the graph above. But they do say that when they disaggregate by cities, they find a clear increase in homicides in cities with large black communities, with the two highest being St. Louis (Ferguson is a suburb of St. Louis) and Baltimore (where the Freddie Gray incident happened). My guess is that homicides rose in all cities, and it only reached statistical significance in mostly-black cities and the cities where the protests were most concentrated.

Here is a graph from the Economist on Baltimore’s homicide rates. In the first graph, you can see that the 2015 homicide rate de-correlates from the 2012, 2013, and 2014 rates immediately after Gray’s death, eventually reaching about 50% more homicides than in any of those previous years. In the second graph, you can see a more traditional presentation of homicide rates, which shows them shooting up after Gray’s death to a level higher than they had been in the previous twenty years.

A followup shows that they stayed elevated for several years afterwards:

Source here. On this chart, it looks like Gray’s death happened after the spike, but this is just an artifact of the recording method they’re using, where 2015 is represented as a single point.

Source here. On this chart, it looks like Gray’s death happened after the spike, but this is just an artifact of the recording method they’re using, where 2015 is represented as a single point.

You can read more people trying to deny this effect eg here, but I don’t find them very convincing.

And after a year or two, the pattern became clearer, and now even the detractors don’t seem to really have their heart in it anymore. The New York Times had an article Deconstructing The Ferguson Effect, subtitled “The idea that the police have retreated under siege will not go away. But even if it’s true, is it necessarily bad?”, which as far as I can tell is as close as the New York Times has ever come to acknowledging that a politically inconvenient fact is true.

Likewise, Vox has an article The Ferguson Effect, A Theory That’s Warping The American Crime Debate, Explained, which makes it very clear that believing in the Ferguson Effect is Problematic, but admits halfway through that if you insist on thinking on a completely literal level, “evidence has begun to mount that there really is something going on.”

I think the proposed Ferguson Effect and the proposed George Floyd effect mutually reinforce each other. The people who believed in the Ferguson Effect would have predicted that the 2020 George Floyd protests would have been followed by a homicide spike, and they would have been right. The people who attributed the 2020 homicide spike to the protests, if they hadn’t previously known about the Ferguson Effect, could have predicted that it existed, and they would have been right too. I think this is a point in favor of both theories.

Other Countries

The pandemic hit almost all countries. Although the Black Lives Matter protests spawned some sympathetic demonstrations around the world, they probably most affected police behavior in the US, where there are large black communities.

So did foreign countries see murder spikes, or not?

The murder rate in the UK fell in 2020-21 compared to the previous year:

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/318385/homicide-rate-england-and-wales/

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/318385/homicide-rate-england-and-wales/

In Germany, there was slightly less attempted murder and slightly more completed murder, but nothing that could really be called a spike.

Source https://www.statista.com/statistics/1045508/number-of-murders-in-germany/. I’m not deliberately trying to move the goalposts by including attempted murder, this is just the graph I was able to find. Even completed murder, while higher than in 2019, was lower than 2017 or 2018.

Source https://www.statista.com/statistics/1045508/number-of-murders-in-germany/. I’m not deliberately trying to move the goalposts by including attempted murder, this is just the graph I was able to find. Even completed murder, while higher than in 2019, was lower than 2017 or 2018.

[EDIT: See this comment on a better way of defining murder in Germany, which shows a smaller 3.7% increase]

Denmark went from 48 murders in 2019 to 49 in 2020:

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/576114/number-of-homicides-in-denmark/

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/576114/number-of-homicides-in-denmark/

I promise I’m not deliberately trying to cherry pick - these are the first three foreign countries that I was able to find good graphs for on Statista (it also has an unreadable graph for China, which I think says Chinese murders declined in 2020).

A commenter was concerned that European countries were a bad comparison, and asked about other countries with lots of guns and high murder rates. I looked into Central America, and found that Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala also all saw murders decline rather than spike in 2020.

No country except the United States had a large homicide spike in 2020, which suggests that the spike was unrelated to the pandemic and more associated with US-specific factors, for which the BLM protests and subsequent pullback of policing in black communities seem to me to be the most obvious suspect.

A Moment Of Griping

Most of these points have already been made in right-wing sources, but have gone unnoticed because respectable people don’t read right-wing sources.

One of these is the Heritage Institute’s piece, What The Media Doesn’t Want You To Know About 2020’s Record Murder Spike. This is an annoying title, basically designed to annoy / drive off / own the libs. It sounds sensationalist and confrontational.

Still, I kind of think the media doesn’t want you to know this.

I mentioned the Intercept piece above, which through selective presentation of data managed to make it look like the protests and homicide spike didn’t coincide. It presents several unconvincing lines of evidence against the protests alone being a main driver (though eventually allows them a supporting role), and in the end focuses on rising gun sales (but guns are mostly bought by white people, and so can’t explain why the homicide spike was so overwhelmingly black). Finally, it concludes that it was “a complex stew of forces”.

Most other media treatments do the same. Vox’s Rise In Murders In The US, Explained gives seven possible explanations, of which two are protest-related, but its overall conclusion is that:

Above all, though, experts caution it’s simply been a very unusual year with the Covid-19 pandemic. That makes it difficult to say what, exactly, is happening with crime rates.

Are there any implications for policy?:

The first priority should be to end the pandemic — ending its potential ripple effects on crime . . . In this sense, Trump’s failures to address Covid-19 may be leading to more violence.

This is basically par for the course. Read New York Times’ or Washington Post’s The Atlantic’s or Pew’s or Voice of America’s articles on this same topic. They’re all exactly the same “It’s a complex combination of factors, we can never know for sure, but probably the pandemic is the most important thing”.

I accept that they had somewhat less data when they wrote their articles than I have now, but many of them have since updated their articles with new data without updating the conclusion, and none of them have since published any correction or indication that they changed their minds.

I won’t waste your time by speculating on why they might do this, or what the implications might be for the truth of everything else you read on these sites. I have tried this so many times and it never works. People keep saying things like “oh, I liked when he made an compelling statistical case showing that the media was completely wrong on this one thing they sounded very confident in, but then he started saying the media is often wrong and biased, and that sounded cliched and conspiracy-ish and right-wing, so I lost interest”.

Conclusion

I think there’s clear evidence that the current murder spike was caused primarily by the 2020 BLM protests. The timing matches the protests well, and the pandemic poorly. The spike is concentrated in black communities and not in any of the other communities affected by the pandemic. It matches homicide spikes corresponding to other anti-police protests, most notably in the cities where those protests happened but to a lesser degree around the country. And the spike seems limited to the US, while other countries had basically stable murder rates over the same period.

I understand this is the opposite of what lots of other people are saying, but I think they are wrong.