Whither Tartaria?

Imagine a postapocalyptic world. Beside the ruined buildings of our own civilization - St. Peter’s Basilica, the Taj Mahal, those really great Art Deco skyscrapers - dwell savages in mud huts. The savages see the buildings every day, but they never compose legends about how they were built by the gods in a lost golden age. No, they say they themselves could totally build things just as good or better. They just choose to build mud huts instead, because they’re more stylish.

This is the setup for my all-time favorite conspiracy theory, Tartaria. Its true believers say we are those savages. We live in the shadow of the Taj Mahal, Art Deco skyscrapers, etc. But our buildings look like this:

The headquarters of Google, one of the richest corporations in the world. A third-rate 1500s merchant would be ashamed to live anywhere as bare.

The headquarters of Google, one of the richest corporations in the world. A third-rate 1500s merchant would be ashamed to live anywhere as bare.

So (continues the conspiracy) probably we suffered some kind of apocalypse a hundred-ish years ago. Our elites are keeping it quiet, and have altered the records, but they haven’t been able to destroy all the buildings of the lost world. Their cover story is that technology and wealth level haven’t regressed or anything, those kinds of buildings have just “gone out of style”.

People say that conspiracy theories are sometimes sublimated expressions of critiques of our society. No mystery what this one is criticizing. Some people don’t like modern architecture. How many? I sometimes see claims like “nobody really likes it”, and certainly it feels intuitively incontrovertible to me that the older stuff is more beautiful. But I know some people who claim to genuinely like the modern style. Are the modern-is-obviously-worse folks just over-updating on their own preferences?

The best source I can find for this is a National Civic Art Society survey, which finds Americans prefer traditional/classical buildings to modern ones by about 70% to 30% (regardless of political affiliation!). In a poll of America’s favorite architecture, 76% of buildings selected were traditional/classical (establishment architects said the poll was invalid, because you can’t judge buildings by pictures). A study of courthouse architecture determined that “[our] findings agree with consistent findings that architects misjudge public likely public impressions of a design, and that most non-architects dislike “modern” design and have done so for almost a century.”

Yet 92% of new federal government buildings are modern. So I think there’s a genuine mystery to be explained here: if people prefer traditional architecture by a large margin, how come we’ve stopped producing it?

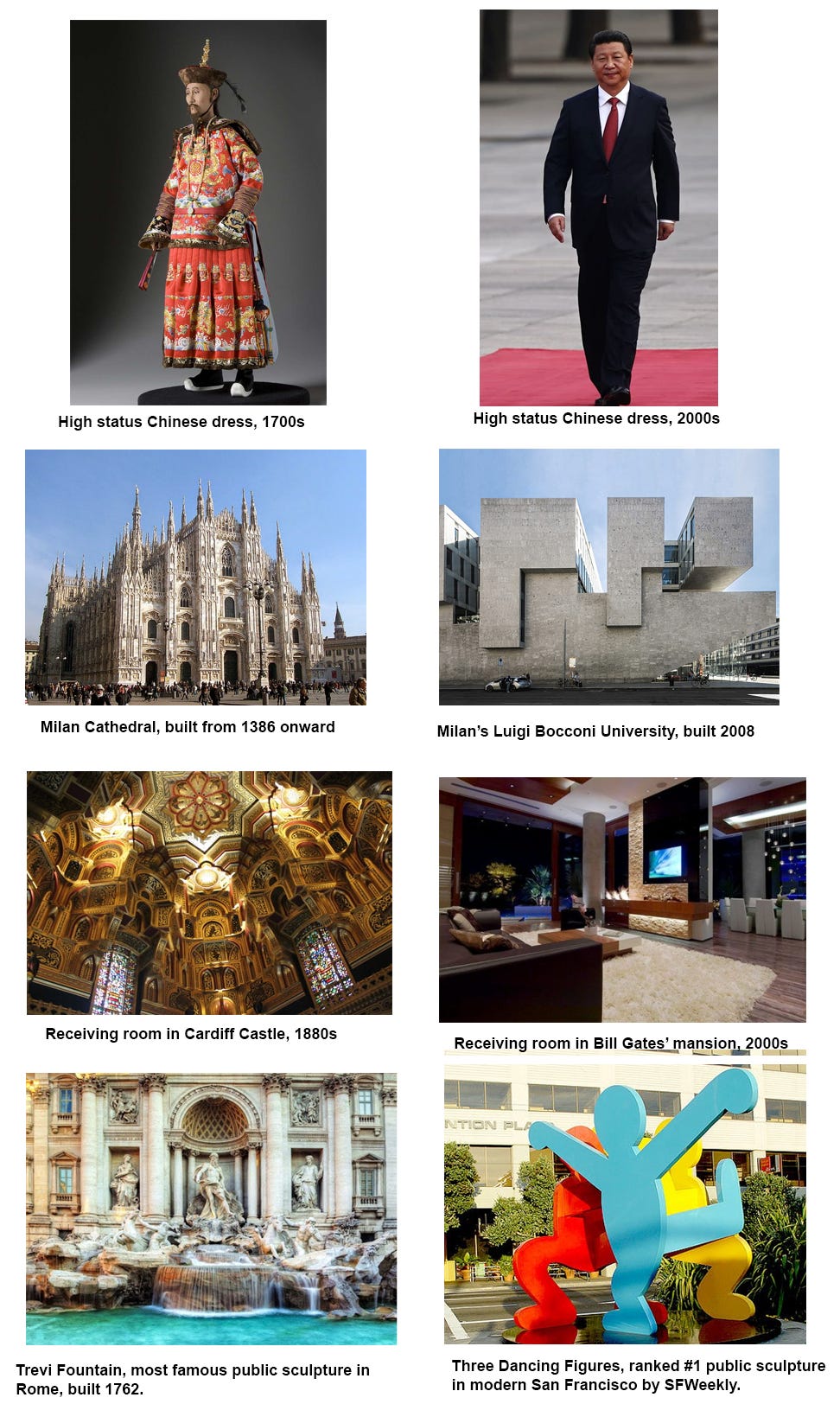

While changes in building materials, cost-cutting, etc might have a role, I think it would be myopic to focus too hard on architecture-specific explanations. The shift from Tartarian to modern aesthetics is consistent across art forms:

I have tried to be as fair as possible here. The first pair is the formal dress of the highest-status person in China in each time period. The second is an architecturally-celebrated building from Milan in each period (the university won the World Building Of The Year award for the the year it was constructed). The third pair is the receiving room of the mansion of a rich person from each period. For the last pair, I used a famous old public sculpture, and searched for the most-celebrated public sculpture from San Francisco, the nearest big city to where I live.

I have tried to be as fair as possible here. The first pair is the formal dress of the highest-status person in China in each time period. The second is an architecturally-celebrated building from Milan in each period (the university won the World Building Of The Year award for the the year it was constructed). The third pair is the receiving room of the mansion of a rich person from each period. For the last pair, I used a famous old public sculpture, and searched for the most-celebrated public sculpture from San Francisco, the nearest big city to where I live.

Older art tends to have bright colors, ornate details, realistic representations, technical skill, and be instantly visually appealing to the average person. Newer art tends to be more abstract, require less obvious skill, and have less direct appeal. Although it doesn’t fit in meme format, I would carry the analogy to poetry (cf. The Fairie Queene vs. William Carlos Williams) and certain pieces of high status music (cf. Mozart vs. Philip Glass). Obviously these are broad generalizations vulnerable to cherry-picking; I’m mostly relying on your common sense here.

There is a lot of writing about “the modernist turn” and the origins of modern art, but I haven’t been able to find anything that links all these artistic fields and tries to explain what happened in general. I am sure you will link me to great resources about this in the comments. Until then, some speculative responses that one might give the Tartarians:

The Modernist Turn As A Change From Flaunting Wealth To Hiding It

Paul Fussell says that pre-Great Depression mansions were beautiful giant houses in the center of town, where everyone could see them and marvel at how rich the owner was. During the Depression, it became awkward to flaunt wealth while everyone else was starving, and the super-rich switched to a strategy of having mansions in the countryside behind lots of hedges and trees where nobody could see them. I remember somebody (not a historian) claiming that the French Revolution had a similar effect on European nobility - it stopped being quite as cool to rub how rich you were in peasants’ faces, and going to court in silks and gold jewelery became less fashionable. The closer you get to the present, the more rich people start to feel like their position is precarious, and other people might resent them - and to act accordingly.

On the other hand, they still want to show off their wealth. So they do it in a plausibly deniable way. They wear a really nice tailored suit or buy an abstract painting that seems completely black until you look closer and see it’s a famous piece of modern art worth millions of dollars. This gets the message across, but it’s not quite the same kind of “f$@k you poor people” as wearing a suit made of gold thread or building a palace with marble statues of griffins in front of every door. If a poor person were to try to complain about how ostentatious and disrespectful you were by having a painting that mostly just looks black, it would fall flat.

I’m a little skeptical of this explanation because I’m not sure that this is actually fooling anyone. In some ways, it’s even more disrespectful to spend millions of dollars on something most people don’t even consider pretty. People don’t really complain when some billionaire buys a Rembrandt, but they did roll their eyes when someone paid $69 million for an NFT.

…Or As Elites Getting More Out Of Touch Than Ever

A lot of people really angry about modern art say the opposite: that in the past elites made at least some effort to cater to the tastes of common people. But due to declining social technology, now elites prefer to signal allegiance to the elite class, and they do that by making buildings which please elite tastemakers and no one else.

It’s still kind of mysterious why not-generally-popular aesthetics would please elite tastemakers, though. Maybe elites are specifically trying to signal not being commoners, by choosing the opposite of commoners’ aesthetic preferences?

This sounds a little conspiratorial for an explanation we originally came up with to counter a conspiracy theory, but I can’t rule it out. It might be helpful to go through a list of countries, see which have more modern vs. traditional architecture, and correlate that with their system of government and level of inequality. My impression is that the more democratic and developed a country, the more modern its architecture, which would require a lot of additional explanation.

…As A Change From Catholic To Protestant Aesthetics

Catholicism traditionally goes heavy on the ornateness, Protestantism heavy on the plainness. Something to do with a Protestant rejection of wealth as too linked to the powers of this world, and trying to get back to the poverty and humility of the original Church. If Protestant aesthetics “won” in a way that affected even people who weren’t thinking in religious terms, that could explain some of the shift.

But the timeline and, uh, spaceline don’t really work. The ornate room from Cardiff Castle is from 1880s Britain (albeit deliberately referencing older styles), and modern Milan is hardly Protestant. I think this might have been one of the threads that fed into this change, but it needs further explanation why it stuck around and spread so far beyond people who cared about religious matters.

…Or As New Timeless Aesthetic Truths

One possibility is that, even though normal people prefer traditional architecture, modern architecture is actually better, and good architects know this.

This is not really the way I think of aesthetics, but I guess it’s possible.

A weaker version of this might be the difference between a very sugary soda and a fine wine. Most ordinary people would prefer the sugary soda, but the fine wine has some kind of artistic value. Right? I don’t know, people always tell me this, but I’ve never been able to enjoy it.

This raises the question of what architecture/art/etc are for. Should eg the government, as a representative of the people, build buildings that people will like? Or should it build buildings with objective artistic value? Maybe in the hopes that this will cause people to appreciate the value, even though this hasn’t worked for the past hundred years? I think you would have a really hard case arguing for the last one, but it’s possible in theory.

You could also frame this as architects deliberately choosing some value other than beauty. Maybe beautiful buildings make everyone feel very proud of their country and connected to their past, but after World War II we realized that nationalism and romanticization-of-history are scary things, and now we’re trying to discourage them. Maybe our civilization is still on probation after a multi-decade-long mass murder spree and we need buildings that carefully avoid inflaming our emotions.

…As A Result Of Increased Cost Of Labor

I’ve added this in because people keep bringing it up in the comments, but I don’t think it works. Sure, it might explain architecture. But I don’t think it explains trends in modern clothing, art, poetry, or sculpture, all of which have also shifted towards decreased ornamentation, symbolism, and realism.

I predict you could buy clothing that looks like this for less than the cost of a nice suit, but nobody does. Is this connected to nobody making buildings that look like the Taj Mahal anymore?

I predict you could buy clothing that looks like this for less than the cost of a nice suit, but nobody does. Is this connected to nobody making buildings that look like the Taj Mahal anymore?

…As A Result Of The Split Between Art And Mass Culture

Modern poems don’t sound very much like the Odyssey. But modern superhero movies are a little bit like the Odyssey. Modern poetry doesn’t have a lot of rhyme or rhythm. But modern pop music does have lots of rhyme and rhythm. Modern gallery art doesn’t have colorful ornate realistic-looking scenes. But modern computer games and animation have lots of those scenes.

Older generations didn’t have superhero movies, pop music, or animated features. Mostly they were missing the technology, but the genres themselves have also evolved. Maybe the existence of pop music makes people less likely to write poems that are “close to” pop music in some kind of artistic space. If you were going to write this today, why wouldn’t you meet up with a garage band somewhere and put it to music?

Or maybe: since pop music is low status, if you want to write high status poetry, you need to make it as unlike pop music as possible, so people don’t accuse your poem of sounding pop-music-y. Or maybe: pop music fulfills what people want out of some poetry much better than the poetry itself does, so if you want an audience, you need to write poetry that fulfills some other kind of need.

Maybe all the people who were looking for easy-to-enjoy things left poetry, gallery art, etc for easier-to-enjoy pursuits like superhero movies, computer games, and pop music, and so poetry and high art were left with disproportionately the sorts of people who were looking for more intellectual pursuits (or who wanted to pretend/signal that they were).

I’m a little skeptical of this one too - what replaced architecture? Or fashion? Also, I still very much want poems that rhyme and I don’t feel like pop music is a perfect substitute for them.

ursula @ursulabrsAs a teacher of poetry what I can tell you for sure is people want poems to rhyme. They want poems to rhyme so bad. But we won’t give it to them[8:11 AM ∙ Sep 6, 2021

ursula @ursulabrsAs a teacher of poetry what I can tell you for sure is people want poems to rhyme. They want poems to rhyme so bad. But we won’t give it to them[8:11 AM ∙ Sep 6, 2021

19,206Likes1,401Retweets](https://twitter.com/ursulabrs/status/1434791291653558275)

…As A Change From Signaling Wealth To Signaling Taste

One use of art is signaling wealth. Pharaohs, nobles, and billionaires would patronize artists, funding the creation of masterpieces that sent the message “look how great I am”. This only works if making beautiful things is expensive. For example, the clothing of the Kanxi Emperor (first picture on left) required servants to create the intricate patterns, dyes that had to be harvested from finicky insects and rare plants, etc. Displaying your ornate dyed objects let everyone know you were rich. With the invention of sewing machines, industrial dyes, rhinestones, etc, even poor people could dress like the Kangxi Emperor. With the invention of photography and printing, everyone could have realistic pictures of whatever they wanted. Actual rich people needed better ways to distinguish themselves.

One attractive option is to switch from signaling wealth to signaling taste. Rich people are more likely to know other rich people and be plugged into rich people social networks (and if they’re not, they can always hire people who are). To signal taste, you need art where the difference between good art and bad art is very hard to discern (if anyone could discern it, then ability-to-discern wouldn’t signal having more taste than average). You want some kind of complicated code that makes sense to tasteful people, feels impenetrable to tasteless people, and (if possible) changes every so often so that tasteless people can’t just memorize it.

I don’t have taste, so I’m agnostic as to the virtues of the particular code that people ended up with. Maybe it involves real but hard-to-explain aesthetic truths, such that far-off civilizations who have no contact with us would independently converge on the same art being better or worse. Maybe it’s arbitrary but self-consistent, the same way lots of features of English grammar (saying “was” instead of “be-ed”) are arbitrary but self-consistent and it’s reasonable to think of that as “good English” and various deviations as “grammatical errors”. Or maybe it’s all totally made up, and elite tastemakers randomly declare stuff that seems cool to them to be the new big thing, almost as a taunt (“look how socially powerful I am, such that I can make people fall in line and call any old garbage Art, even this stuff”). Cf. the Ern Malley Hoax. Probably all three of these are true in different subfields at different times.

A friend, more in touch with the pulse of rich-people-society than I am, objects that billionaires still like buying paintings by Old Masters. But I don’t think that contradicts this. Being able to buy a Rembrandt still signals wealth fine: Rembrandts are in limited supply and everyone knows they’re expensive. But a modern painter with Rembrandt’s skillset wouldn’t be able to make it big - their talents are no longer in short supply.

Why Does This Matter?

Partly because art is nice and we should want more beautiful things or at least try to understand where our beautiful things come from.

Partly because exploring these questions can shed light on broader questions of class, signaling, and how intellectual/cultural/economic elites relate to their social inferiors. It seems like premodern artistic elites and commoners were on the same page. Then something happened to put them on different pages. Why? How does that relate to the formation of classes in general? Is society better off if elites successfully win the support of commoners by patronizing art that they like, or win their respect by surrounding themselves in awe-inspiring trappings of wealth? Or if elites are barred from using that particular propaganda lever?

And partly because modern art and architecture are examples of fields talking to themselves. In a way, this is good - they’ve successfully implemented a technocracy where the best and brightest are able to pursue their own visions rather than pander to the masses. In another way, it’s confusing - public art, architecture, etc is supposed to be to the benefits of residents, but it seems like those residents can’t get their voices heard.

Every field is shaped by some combination of ground truth - the thing they’re supposed to be studying - and incentives. Economic theories in capitalist and socialist countries will share some characteristics - there’s a real world with real economic laws that are hard to miss - but they’ll also take different paths depending on what the surrounding society celebrates vs. condemns.

And the incentives depend on who they’re trying to impress. Sometimes fields are trying to impress the public - Justin Smith writes about so-called “Spiderman Studies” classes where college humanities departments try to look hip and in-touch to attract more students. Other times fields are definitely not trying to do this - you get status by appealing to other experts in your own guild. Doctor Oz might be the most famous and publicly-beloved doctor, but he has zero credibility in the medical field. I may have a popular blog where I write about psychiatry (and I try not to lapse into Doctor Oz style charlatanry) but the blog doesn’t raise my status in the medical hierarchy at all, and might actively hinder it. Best-case scenario, you want a field that talks to itself enough that you get status for impressing other experts with your expertise, not for impressing the public with demagoguery.

But if you talk to yourself too much, you risk becoming completely self-referential, falling into loops of weird internal status-signaling. Science has a safety valve here - they’ve got to at least contact the real world enough to do experiments. But humanities fields (or social sciences where experimentation is hard and wrapped in layers of interpretation) don’t have that defense. If their signaling incentives lean too far one way, they surrender to the public so cravenly that it’s pointless for them to have expertise at all. If they lean too far the other way, they become actively contemptuous of the public, ignore all criticism, and the whole edifice risks becoming vulnerable to any Sokal-style attack that uses the right buzzwords.

Art is interesting because in some ways it’s less “about something” than other fields are. Maybe there are real timeless aesthetic truths, but they’re a lot harder to detect than the timeless truths of math or science, and you can do art history pretty well without worrying about them at all. That makes it an unusually clear laboratory for examining the status incentives within fields. Sometimes the definition of “good art” changes. It probably wasn’t the discovery of a new timeless aesthetic truth, so what was it?

The turn is an especially vivid example of a shift in the art world. If we understood what factors shaped it, maybe we would learn more about the factors shaping other fields with clearer targets.