Your Book Review: On The Natural Faculties

[This is the second of many finalists in the book review contest. It’s not by me - it’s by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done, to prevent their identity from influencing your decisions. I’ll be posting about two of these a week for the next few months. When you’ve read all of them, I’ll ask you to vote for your favorite, so remember which ones you liked. - SA]

I.

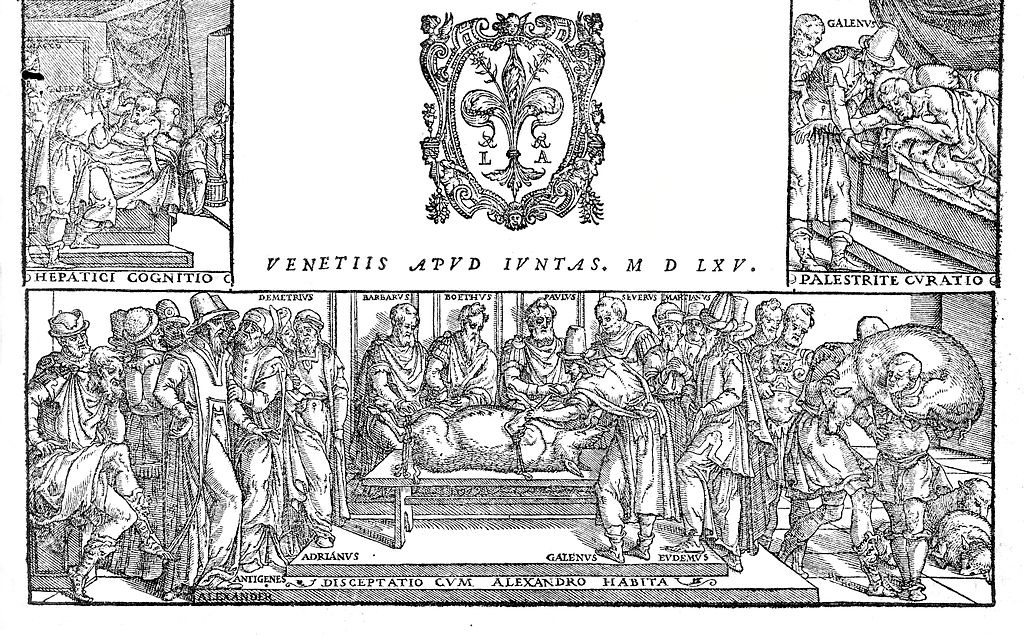

If you’re looking for the whipping boy for all of medicine, and most of science, look no further than Galen of Pergamon.

As early as 1605, in The Advancement of Learning , Francis Bacon is taking aim at Galen for the “specious causes” that keep us from further advancement in science. He attacks Plato and Aristotle first, of course, but it’s pretty interesting to see that Galen is the #3 man on his list after these two heavy-hitters.

Centuries went by, but not much changed. Charles Richet, winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, said that Galen and “all the physicians who followed [him] during sixteen centuries, describe humours which they had never seen, and which no one will ever see, for they do not exist.” Some of the ‘humors’ exist, he says, like blood and bile. But of the “extraordinary phlegm or pituitary accretion” he says, “where is it? Who will ever see it? Who has ever seen it? What can we say of this fanciful classification of humours into four groups, of which two are absolutely imaginary?”

And so on until the present day. In Scott’s review of Superforecasting , he quotes Tetlock’s comment on Galen:

Consider Galen, the second-century physician to Rome’s emperors…Galen was untroubled by doubt. Each outcome confirmed he was right, no matter how equivocal the evidence might look to someone less wise than the master. “All who drink of this treatment recover in a short time, except those whom it does not help, who all die,” he wrote. “It is obvious, therefore, that it fails only in incurable cases.”

Scott then says,

After hearing one too many “everyone thought Columbus would fall off the edge of the flat world” -style stories, I tend to be skeptical of “people in the past were hilariously stupid” anecdotes. I don’t know anything about Galen, but I wonder if this was really the whole story.

This strikes me the same way. The more I read about history, the more I realize that it was made up of people just like us. They didn’t always have the same tools we do, and they made some weird mistakes, but they weren’t any less intelligent than we are. Some of them were pretty smart.

I’m also concerned that this criticism doesn’t pass the sniff test. If Galen was really a moron, why did he have such a lasting impact? Most philosophers, including great ones, aren’t even known in their own time. There must have been something about Galen’s works that kept them around for thousands of years.

All this makes me very suspicious. Was Galen actually a dope? Or did someone pull an intellectual hit job on the guy? If so, why? What was he actually like, and why did he have such a huge influence?

When you press a seashell into the sand, it leaves an impression that is its own shape. For some reason culture isn’t like this. Great works and people seem to leave impressions in the culture that are different from their own shape. People who read Frankenstein are often surprised to learn that “Doctor” Frankenstein was about 19 (Victor made the creature during the summer after his second year at university; he was an undergrad), and that his “monster” can not only speak, but is articulate and sensitive. Whatever Galen was actually like, the modern stereotype of him is probably inaccurate.

So for these reasons and others, I decided to review one of Galen’s books.

II.

First, a little biographical context.

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (henceforth “Galen”) was born in Pergamon, a town in modern-day Turkey, in 129 CE. At the time, it was a part of the Roman empire, and a major intellectual center. Galen’s father was an architect; while rich, he was not considered to be particularly high status. Since there was little pressure for his son to go into a traditional career, instead of the “safe” subjects of literature and rhetoric that most Romans studied, Galen got an unusual education in mathematics and geometry.

(His father’s patient encouragement has its foil in his mother, who “flew into rages and bit her servants, a practice of which Galen disapproved.”)

When Galen was a teenager, however, his father had a dream where the god of medicine appeared and told him that his son should study medicine, so Galen started training as a doctor.

During this training Galen became familiar with the writings of Hippocrates, who had lived about 600 years earlier. Hippocrates had introduced the idea of the four humors to medicine — four fluids that congeal together to form our flesh and organs, and which co-mingle in our veins in their liquid form. Hippocrates came up with this system, but Galen would be the one to make it world-famous.

I could try to describe the theory myself, but actually Hippocrates does a great job on his own:

The Human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed. Pain occurs when one of the substances presents either a deficiency or an excess, or is separated in the body and not mixed with others.

All disease and illness, in this system, were the result of an imbalance in the four humors. From this perspective, treatments like bloodletting make perfect sense. By opening up the veins, the excessive humors drain away, leaving the patient more balanced — in better humors.

Long-term trends towards any of the humors were responsible for what we would call personality. Hence the terms sanguine , phlegmatic , melancholy and so on for different personal traits and emotional conditions.

This is the theory that he would put his weight behind, and which he would eventually be responsible for bringing to the majority of the western world.

When Galen was 19, his father died, leaving him independently wealthy. Hippocrates wrote that a good doctor should travel, so Galen ended up spending a decade studying with medical experts from various schools in cities all around the Mediterranean, including Alexandria.

After this, he came back to Pergamon where he got a job as the doctor treating the gladiators of the city. This was an unusual step for someone of his wealth and education, because despite their popularity as a form of entertainment, gladiators at the time were considered extremely low-class.

It’s not clear why he took this job, but it seems likely that it influenced how he thought about medicine. Spending long hours stitching gladiators back together gave him a detailed knowledge of human anatomy, which other doctors of the time lacked. It sounds like he did a great job, too, because only five of the gladiators died during his time there — compared to 60 under the guy who had the job before.

Eventually all roads lead to Rome, of course, and Galen arrived in 162 CE. His lectures and demonstrations made such an impression, and ruffled so many feathers, that he was afraid of getting poisoned by the Roman doctors and eventually left to save his life. In 169 CE, however, a great plague (probably smallpox) broke out, and Marcus Aurelius summoned him back to Rome to serve as court physician. Marcus Aurelius died the next year (according to some sources, of the plague), but Galen ended up with a longterm post in Rome as physician to the new Emperor, Commodus.

Galen himself died some time between 199 and 216 CE, at the the ripe old age of between 70 and 87.

It’s hard not to notice just how famous Galen was in his own time. Marcus Aurelius described him as “primum sane medicorum esse, philosophorum autem solum” — first among doctors and unique among philosophers (one wonders if Galen might have influenced the Emperor’s own philosophy). Forgeries and unscrupulous editions of his work were such a problem during his lifetime, he had to write a book called On My Own Books to try to sort it all out. Among other things, he complains that his servants were stealing private letters he had written to friends and circulating bootleg copies of them as medical advice.

Galen was an incredibly prolific writer. Wikipedia claims that he produced more works than any other author in antiquity, maybe up to 600 treatises, and possibly employed 20 scribes at one point. While these particular claims are hard to substantiate, he did leave behind a whole lot of books.

Fires and the various other mishaps that are guaranteed to happen to classical texts destroyed many of his works. Some of this even happened during his own lifetime, and in On My Own Books he seems surprisingly relaxed about so many of his works being lost:

The books of many others perished at that time, as did all those of mine which were located in that storehouse; and none of my friends in Rome admitted to having copies of the first two books. Since, then, my followers prevailed upon me to write the same treatise again, I thought that I should give this explanation regarding the previously distributed books, in case anyone in the future finds them and wonders why I should have written a treatise twice on the same subject.

Even with these losses, huge amounts of his work has survived. It’s hard to get an exact count, but Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia by Karl Gottlob Kühn, compiled around 1833 and for a long time the definitive edition, contains 122 different works in 22 volumes. That’s a lot.

Despite this, I was surprised how hard it was to get my hands on primary source copies of his works (in English). Because of our own plague, I was limited to finding sources online — but for most classical works, this is pretty easy. Marcus Aurelius was a contemporary of Galen, and it’s not too hard to find multiple different translations of Meditations (though admittedly Marcus may have a slightly wider appeal).

Part of this might be that Galen’s works are very badly organized. Every secondary source I read on the Galenic corpus is full of griping about how confusing the whole thing is. Galen wrote in Greek, but many of the original versions of his books are lost, leaving us only with Arabic or Latin translations, or Latin translations of earlier Arabic translations. Some of the books appear under different titles in different places, and sometimes the works are only indexed under abbreviations of those titles. Some of them probably were never intended for publication (those bootleg letters I mentioned above), and so may not have official titles or versions at all. Forgeries of his works in various languages continued well on into the Renaissance.

Galen himself was very unclear on how to think about the documents he produced. At one point in On My Own Books , he starts off by talking about a piece of writing he did “as an exercise for myself”, and then immediately turns around and mentions that he gave it to friends, who in turn gave it to their friends. Needless to say, the whole thing is a mess, the scholars seem very agitated.

I chose to review the longest piece I could find, which is On the Natural Faculties , specifically the translation by Arthur John Brock, which was the only translation I was able to track down. This also seemed like a good choice because, instead of being a treatise on a more limited topic like diet, the pulse, or bones, this book serves as more of an introductory textbook to what today we would call biology.

III.

On the Natural Faculties is divided into three books, though if the three books have any structure to them, I wasn’t able to figure it out.

Galen is pretty straightforward in naming his pieces, and this book is about him trying to describe all of the “natural faculties”. This doesn’t really correspond to any modern concept, but essentially he means the fundamental or basic biological functions common to all living things. He begins by contrasting the functions of the soul, like feeling and voluntary motion (we might say “mental functions”), which occur only in animals, with the natural functions common to both animals and plants. You could maybe translate “natural faculties” as something like “basic biological functions”.

I had always heard that Galen was a Hippocrates stan, but right from the get-go he’s mentioning Aristotle in the very same breath (though he reminds us that Hippocrates “lived much earlier than Aristotle”). When describing the natural faculties, he seems to base them off of Aristotle’s physics more than Hippocrates’ humors.

Aristotle’s physics is a system I mostly know secondhand from the descriptions offered by Thomas Kuhn (for an example, take a look at this piece). Kuhn stresses that this system is hard for a modern mind to understand and even harder to explain, so I was surprised at how intelligible Galen’s account is. Maybe reading Kuhn’s description prepared me to understand what Galen has to say, but either way, it’s great. I think Galen does a better job than Kuhn. Basically he says, look, there are different kinds of motion:

If that which is white becomes black, or what is black becomes white, it undergoes motion in respect to colour; or if what was previously sweet now becomes bitter, or, conversely, from being bitter now becomes sweet, it will be said to undergo motion in respect to flavour … when a warm thing becomes cold, and a cold warm, here too we speak of motion; similarly also when anything moist becomes dry, or dry moist.

He goes on to suggest that the natural faculties are more advanced forms of motion, possibly built up out of the combination of simpler forms of motion.

(Kuhn treats the Aristotelian perspective as if it was the common sense of the ancient world, but the fact that Galen has to describe it in such detail makes me wonder if that was really the case.)

That’s the framework. What the exact set of natural faculties are, however, is less clear.

In book one he focuses on three faculties in particular — genesis, growth, and nutrition — and provides lots of arguments that (for example) the body’s ability to grow is different from its ability to sustain itself. In book three he gives a different list of four — the attractive, retentive, expulsive, and alterative faculties — but he also suggests that these are “handmaids of Nutrition”.

Elsewhere he says that genesis is not “a simple activity of Nature” but instead is “compounded of alteration and of shaping.” He also mentions faculties like “adhesion” and “presentation”. The particulars are pretty confusing, but the general gist is clear. Galen wants to lay out all the different faculties and their sub-faculties (and sub-sub-faculties?) so that the reader can understand the workings of the body.

Galen makes it pretty plain that he thinks that diseases are caused by failures or overactivity of the different principles. For example, he says that in leprosy “there is adhesion of the nutriment but no real assimilation”. One faculty is working but the other is disordered. If you want to be a good physician, he says, you need to understand all these faculties so you can identify diseases (tell what faculties are misfunctioning) and treat them — “how are you going to be successful in treatment, if you do not understand the real essence of each disease?” he says.

The four humors do make their way into this mix eventually, especially in the second and third books. (Though the translator often insists on translating “humor” as “juice”, which makes me very uncomfortable.) The relationship seems to be that the humors are the building material of the body, but that all the activity is carried out through the natural faculties. The student needs to know the humors to understand what is being moved around, but the humors are primitive. To Galen, biology is all about these faculties shuffling, transforming, and combining different humors.

VI.

Anyways, that’s what Galen wants to be talking about. But about halfway through book one, he goes entirely off the rails and never really gets back on track.

The thing that sets him off is other schools of medicine. It’s clear that Galen cannot stop thinking about them. They invade his every thought; he is beleaguered by them. I would seriously believe that he loses sleep over them.

Some of the commentators I’ve read suggested that Galen was an arrogant man — one said he saw in Galen “the blind assumption that he alone was graced with the ability to bring Hippocrates’ work to completion”. My sense of Galen was that he is a man who is constantly exasperated. He is just trying to write basic pieces about how to be a good physician and philosopher, and people keep descending on him with the most unbelievably pedantic arguments. Book One of On the Natural Faculties is divided into 17 sections, and he spends half of the first section hedging around ways people could potentially take his words in the wrong ways.

These sound more than a little like intrusive thoughts, and it’s tempting to think that he’s blowing this all out of proportion. But from what I know about Galen’s life, it seems likely that he really was getting into disagreements all the time, and probably really did need to worry about people quoting his work out of context. One article in The Lancet describes him as “a public figure, known and recognised by many, accosted in the streets, challenged to debate.” It’s easy to imagine how being accosted in the streets might work its way into your head.

Either way, these concerns absolutely consume him. He keeps getting drawn off on different tangents, before trying to return to the main thread with statements like:

I said, however, that I was not going to enter into an argument with these people, and it was only because the example was drawn from the subject-matter of medicine, and because I need it for the present treatise, that I have mentioned it.

Let us pass on, then, again to another piece of nonsense; for the sophists do not allow one to engage in enquiries that are of any worth, albeit there are many such; they compel one to spend one’s time in dissipating the fallacious arguments which they bring forward. What, then, is this piece of nonsense?

Now, we usually refrain from arguing with people whose principles are wrong from the outset. Still, having been compelled by the natural course of events to enter into some kind of a discussion with them, we must add this further to what was said…

Since, then, we have talked sufficient nonsense — not willingly, but because we were forced, as the proverb says, “to behave madly among madmen” — let us return again to the subject of urinary secretion.

But, as I have said, one is driven to talk nonsense whenever one gets into discussion with such men. Having, therefore, given a concise and summary statement of the matter, I wish to be done with it.

Of course, in the very next paragraph, he is immediately drawn back into a discussion of their shortcomings!

In some ways, On the Natural Faculties is less of a medical treatise and more of a fascinating snapshot of the state of the academic medical world in the latter half of the second century CE. The tone sounds really contemporary in a lot of ways, and has a quality of acrimonious quibbling that is more than a little familiar, though I don’t think modern physicians are likely to be poisoned by their colleagues (but what do I know).

V.

We’ve established that Galen has a problem with other experts and schools of medical thought. That leaves us wondering how justified he is. Is he criticizing them for real problems in their work, or is this just partisan squabbling?

What are the things that he takes such issue with from these other schools? I think there are two things he’s mostly complaining about.

The first thing that really sets Galen off is sectarian dogmatism. “Everyone becomes like the first teacher that he comes across,” he says, “without waiting to learn anything from anybody else.” He bemoans sectarian partisanship and, in classic doctor fashion, uses a weird hygiene metaphor, calling it “excessively resistant to all cleansing process”. It is “harder to heal than any itch”.

The fact is that those who are enslaved to their sects are not merely devoid of all sound knowledge, but they will not even stop to learn!

This is kind of tragicomic, because two of the main things Galen is accused of are 1) blindly following whatever Hippocrates said about medicine and 2) leading centuries of physicians to blindly follow whatever he wrote!

It’s hard to know how blindly Galen is following the teachings of Hippocrates. On the one hand, he does refer to him as “most divine Hippocrates” at least once. On the other hand, he is open to pointing out the (rare) cases where he thinks Hippocrates has overlooked something, and even talks about how he wishes his opponents would criticize Hippocrates more directly! When someone disagrees with a whole suite of his intellectual heroes, he says, “now, one cannot be blamed for not agreeing with all these great men, nor for imagining that one knows more than they; but not to consider such distinguished teaching worthy either of contradiction or even mention shows an extraordinary arrogance.”

Maybe other physicians really did follow Galen’s writing blindly in the centuries following his death. I’m not sure anymore. But Galen certainly can’t be blamed for it. He could not be clearer in stating that this is exactly what the student of medicine should avoid doing.

It would be tempting to pass this all off as one-sided; “stop listening blindly to your teachers and listen blindly to me!” I don’t get that sense.

First, we know that Galen studied all over the ancient world, so he was exposed to all sorts of ways of doing medicine. He practiced what he preached. It’s hard to know how fair a representation he’s giving of the other schools of thought, but he writes as though he has them all memorized, and he certainly was in a position to frequently get into debates with them. When he tells us that they’re uncritical, I’m tempted to believe him.

Second, Galen makes a serious point to try to convince the reader of his positions. He’s not just stating “facts” and expecting you to bow down at his feet. He’s engaging with opposing points of view and trying to make compelling arguments that he thinks will convince his readers.

VI.

Finally, I don’t buy this because nowhere is Galen asking people to listen blindly to anyone, least of all himself. Because the second thing that REALLY sets Galen off is when people aren’t empirical enough! He constantly ridicules, in pretty harsh language, those who remain unconvinced by observation and experiment.

Asclepiades, one particularly hated adversary, is charged with “bidding us distrust our senses where obvious facts plainly overturn his hypotheses.” Asclepiades has rather unusual opinions about the urinary system, and in one particularly strong example, Galen asks rhetorically (and sarcastically!),

I do not suppose that Asclepiades ever saw a stone which had been passed by one of these sufferers, or observed that this was preceded by a sharp pain in the region between the kidneys and the bladder as the stone traversed the ureter, or that, when the stone was passed, both the pain and the retention at once ceased. It is worth while, then, learning how his theory account for the presence of urine in the bladder, and one is forced to marvel at the ingenuity of a man who puts aside these broad, clearly visible routes, and postulates others which are narrow, invisible—indeed, entirely imperceptible.

Other schools are also attacked for denying “observed facts” or even “obvious facts”. Meanwhile, people who draw incorrect conclusions but respect the facts are praised.

Galen cares a lot about physicians basing decisions on empirical observation. We know that he’s serious about this because of the many disturbing vivisection experiments he describes in great detail.

In discussing digestion, he says, “I have personally, on countless occasions, divided the peritoneum of a still living animal and have always found all the intestines contracting peristaltically upon their contents.” He describes an experiment where you vivisect an animal, cutting away different coats of the esophagus, “then give the animal food and you will see that it still swallows although the peristaltic function has been abolished”. When describing the action of the stomach, he suggests that you can fill an animal with liquid food — “an experiment I have often carried out in pigs” — and cut them open “after three or four hours.”

He really seems to want his readers to try these macabre exercises at home. “You may observe this yourself,” he says, “if you will try to hit upon the time at which the descent of food from the stomach takes place.” Fellow physicians are criticized for their lack of anatomical experience in the same way. “If he had ever practised anatomy, he might have known that the outer coat of the bladder springs from the peritoneum and is essentially the same as it.”

The most extreme example comes from a debate with the disciples of Asclepiades about the function of the ureters, trying to convince this rival school that urine flows from the kidneys to the bladder through these channels. After exhausting his rhetorical options, Galen turns to empirical anatomy. First he shows them, in a dead animal, that the ureters connect the two structures. This isn’t enough. Next he shows them “in a still living animal, the urine plainly running out through the ureters into the bladder.” This doesn’t change their minds either.

Next he takes a live animal, ligates the ureters, bandages the animal up, and lets it go. When he opens it up again later, he finds the ureters “quite full and distended”, and when he removes the ligature, everyone can see the urine flow into the bladder.

You’d think the story would end there, but not so. Instead, says Galen, “tie a ligature round [the animal’s] penis and then … squeeze the bladder all over.” He points out that nothing goes back through the ureters to the kidneys, demonstrating that the conveyance is a special, one-way action. He goes on like this for a while. Let the animal urinate and tie a ligature around one ureter but not the other. Cut open both the ureters and see the urine “spurt out of it”. Bandage the animal up and open him up later to discover his insides full of urine and the bladder empty. “Now, if anyone will but test this for himself on an animal,” Galen concludes, “I think he will strongly condemn the rashness of Asclepiades.”

Today we know that Galen was wrong, and that humorism isn’t a great way to think about medicine. But whatever Galen might have been lacking, it certainly was not the empirical bent. He was no armchair philosopher, and was more than happy to cut up lots of animals to make a point about the function of the ureters.

This is funny because, again, this is the opposite of the story we’re told about Galen. He’s described as a pre-scientific or even unscientific thinker, believing that experimentation and investigation are a waste of time. Clearly this isn’t the case, and he made full use of all the resources available to him. We know that human dissection was prohibited in the empire, but Galen worked with gladiators, so we know that he had firsthand experience with human anatomy. He certainly was unafraid, even eager, to practice animal dissection and vivisection. Other doctors of the time didn’t seem to do either of these things, or at least didn’t do nearly as much, and so Galen starts looking more and more like a lone light of empiricism in the wilderness.

(However extreme and disturbing his methods may be.)

VII.

In view of this, it’s extremely depressing to see Tetlock write, “yet Galen never conducted anything resembling a modern experiment.” Galen isn’t here to respond, but if he were, I imagine he would say: and yet Tetlock never conducted anything resembling a basic literature review!

Galen definitely isn’t as charitable as we might want him to be. He calls some of the ideas he disagrees with “impossible, nay, perfectly nonsensical”, or “stupid—I might say insane”. His intellectual rivals “are like slaves” he says, “caught in the act of stealing … quite bewildered, and while the one says nothing, the other indulges in shameless lying.”

But I’m pretty sympathetic to Galen’s position, because his contemporaries really do sound like idiots. Of course, all this is being filtered through Galen’s own account, but if he’s describing them with any accuracy, he is totally fair in saying that they have no idea what they are talking about.

Some of the positions he argues against include:

-

Urine passes into the bladder in the form of vapors, rather than being secreted by the kidneys and passed through the ureters to the bladder. Galen argues against this first by pointing out that the kidneys and bladder are connected by the ureters (which must have some purpose), and second by the extensive evidence from vivisection that I mentioned above.

-

Fetuses are constructed piecemeal in the uterus, instead of beginning small and growing to the size they are at birth. Galen argues against this by describing an observation mentioned by Hippocrates, where he saw a very early miscarriage in which he noticed that the heart of the fetus was “so small as to differ in no respect from a millet-seed, or, if you will, a bean.”

-

Swallowing is powered by the “impulse from above” (I think he means gravity), rather than the action of the muscles. Galen argues against this first by pointing out that the “oblique situation of the gullet” means that gravity wouldn’t be sufficient, and second by describing vivisections he had conducted that showed swallowing to be caused by the action of different parts of esophagus. He also mentions something about pouring water down a dead man’s throat, but I didn’t understand that part of the argument.

Galen is certainly right about some things and wrong about other things. He mentions that the veins and arteries are connected to each other, something that had apparently escaped everyone else’s notice. But he also thinks that air is taken in through the capillaries near the skin. He has some unusual ideas about pregnancy, and reports that corn will spontaneously draw water out of nearby earthen jars and increase in weight, which I’m pretty sure is not true. But compared to his contemporaries, he seems to be very much on the right track.

In fact, I was surprised by how modern Galen’s reasoning seems. At one point he discusses magnets, and argues against an atomic explanation of their action. Before you laugh, remember that the modern explanation is electromagnetic fields, which look a lot more like one of Galen’s natural faculties (a tendency for mutual attraction over distance) than they do Epicurus’ view that “the atoms which flow from the stone are related in shape to those flowing from the iron, and so they become easily interlocked with one another”.

In making this argument, Galen first points out that the idea that nature has “powers which attract” is sufficient to explain the observations. Next he says that since the proposed entanglement can’t be observed, it’s not clear why anyone would prefer this explanation to another. Even if we do allow it, he says, it doesn’t explain why a piece of iron that has previously touched a lodestone will then go on to attract other pieces of iron. The atomic explanation predicts that this shouldn’t happen!

Then he brings out cases from his own experience, saying, “I have seen five writing-stylets of iron attached to one another in a line, only the first one being in contact with the lodestone, and the power being transmitted through it to the others.” Then he uses a thought experiment! “Now, if you imagine a small lodestone hanging in a house, and in contact with it all round a large number of pieces of iron, from them again others, and so on…” He continues on in this vein for a number of paragraphs.

This strikes me as a very modern way to make an argument. It’s how I would make an argument today — none of the intellectual arsenal seems to be missing! In fact, Galen uses thought experiments quite frequently. There’s one in particular he loves, about children making balloons out of the bladders of pigs, which he uses a couple times to demonstrate that only Nature has the ability to actually make things grow, rather than just distend them.

Nature (always capitalized) is a concept Galen comes back to time and time again, which he uses as an underlying principle for his arguments. Usually he talks about how Nature exercises forethought for the animal’s well-being and survival, or talks about how Nature is “artistic”, making everything for a purpose. A constant criticism he makes of other schools is against their claims that various ichors, tissues, or organs exist without a purpose. Nature doesn’t make things without a purpose! he shouts.

“Nature”, described in this way, ends up sounding a lot like evolution. Of course, Galen had no concept of evolution, but it’s very interesting to see that he was using a functionally equivalent concept hundreds of years before Darwin. It’s not clear if this is a concept he developed himself or if he inherited it from some earlier thinker, but clearly someone, in looking at biology, noticed that the principle “everything exists for a purpose” was a pretty good starting place for making arguments that turned out to be true.

Nature takes on the exact same role in his arguments that evolution would take on in ours:

“Your school of medicine says that the ureters don’t do anything? Then why are they there? We know that this animal was created by Nature, why would she include these structures if they were truly useless?”

“Your school of medicine says that the ureters don’t do anything? Then why are they there? We know that this animal evolved through natural selection, wouldn’t selective pressure remove these structures if they were truly useless?”

VIII.

Galen’s idea of humorism is more detailed and nuanced than the picture of humorism I’ve gotten from secondhand accounts. For one thing, he’s not limited to just four humors. He refers to different types of blood and suggests that there is a “sweet” phlegm and a “bitter or salty” phlegm, the former useful to health and the latter dangerous. At one point he mentions that Praxagoras describes a theory of eleven humors, and even says, “this is not a departure from the teaching of Hippocrates; for Praxagoras divides into species and varieties the humours which Hippocrates first mentioned”.

As much as modern authors like to describe the humors as imaginary, Galen routinely talks about them as if he were actually collecting and measuring them! In a section where he talks about the properties of different drugs, he describes at length how they will evacuate more or less of the various humors in different seasons or from people of different ages.

One might be tempted to dismiss this as metaphor or inference — “probably Galen means that you can see the evidence of evacuation” — but how are we to take it, then, when he describes the humors in terms of the volume produced? “Who does not know,” he says, “that if a drug for attracting phlegm be given in a case of jaundice it will not even evacuate four cyathi [about 4 oz.] of phlegm?” I’m not sure what is being evacuated here, or how he collected it, but he certainly seems to be measuring something.

Galen makes even more sense when talking about other drugs. He has a whole digression on antivenoms, where he concludes by saying that after the treatment has been applied, “we can, in fact, plainly observe these poisons deposited on the medicaments.” He describes a case where manual traction was insufficient to remove a thorn from a young man’s foot, but some kind of “medicament” removed it easily. He mentions that some people claim that the thorn only falls out in this case because the medicament reduces inflammation. Not so, says Galen, who points out that while there are anti-inflammatory drugs as well, those don’t do anything to draw out embedded bodies.

He doesn’t offer enough detail and I don’t know enough medicine to discover how many of these claims are correct, but it’s certainly more nuanced reasoning than he is usually given credit for.

Remember that quote that Tetlock used to dunk on Galen? “All who drink of this treatment recover in a short time, except those whom it does not help, who all die. It is obvious, therefore, that it fails only in incurable cases.”

I haven’t been able to confirm its source. Everything attributes it to Galen, but they all point to earlier secondary sources — people who were not Galen but who were supposedly quoting him. Tetlock doesn’t cite one of Galen’s many works — he cites Druin Burch’s 2010 book, Taking the Medicine: A Short History of Medicine’s Beautiful Idea, and Our Difficulty Swallowing It. Now, Taking the Medicine does include that quotation, but as far as I can tell, it doesn’t cite a source.

The other secondary sources I found seem to lead back to the 1998 book, Where’s the Evidence? Debates in Modern Medicine , by William A. Silverman, but he doesn’t say which of Galen’s works this quote supposedly comes from. In fact I can’t find any sources from before 1998 that include any fragment of this quote at all. It’s not looking good for the authenticity of this quote.

(I was going to suggest that maybe this quote might somehow be a mistaken bastardization of the “dormitive potency” line from Molière’s The Hypochondriac , since that’s what it reminds me of. But I looked and I actually wasn’t able to find that line in the play, so…)

As with many other things, it’s ironic that people haven’t actually read Galen, because this is yet another thing that Galen complains about in this book. Back in his day, the guy no one read but everyone pretended to was Aristotle. “The fact is, these people seem to me to have read none of Aristotle’s writings, but to have heard from others how great an authority he was on ‘Nature’…” I guess little has changed in the past 1,800 years.

You know, reading about Galen reminded me of someone… a physician… trained all around the world… a prolific writer… constantly drawn into disputes about philosophy and empirical practice… who am I thinking of…

IX.

Ok, so it looks like there was an intellectual hit job on Galen. Why?

I see two possibilities. The first is that Galen’s followers may have really been as bad as people say. To take one example: Jacobus Sylvius, in the 16th century, was a huge supporter of Galen. When his student Vesalius called into question Galen’s knowledge of anatomy, by performing his own dissections, Sylvius rushed to Galen’s defense. Despite being the first professor to teach anatomy of the human corpse in France, Sylvius said that Galen had not erred, but “probably the human body had changed since then.” Further, he said that advance beyond Galen’s understanding was impossible.

(I’ll note, though, that the oldest source I can find for these claims is a Catholic book from 1913, so if there’s some reason to suspect that the Catholic Church wanted to put out an intellectual hit on Jacobus Sylvius, then maybe disregard all this.)

If Galen’s other supporters were anything like this — and my sense is that they were — then it’s no surprise that there was a reaction. Galen’s teachings had ossified, and when the old guard was swept out, it damaged Galen’s reputation just as much as it destroyed his school of thought. All this despite the fact that Galen probably would have endorsed the work of Vesalius, who was actually performing dissections, over the work of those who merely studied his texts!

Another is that Galen may have been a casualty of the fight between a corpuscular and an essentialist worldview. You’ll remember that Galen’s thought was as much based in the work of Aristotle as it was based on the work of Hippocrates. All things can be explained through different kinds of “motion”, or faculties. In this paradigm, other kinds of explanations are unnecessary.

Earlier I mentioned a passage where Galen makes an argument about how magnets work, and how he takes issue with the atomic explanations offered for this phenomenon. It’s not just magnets; Galen is strongly opposed to this entire worldview. In a particularly comic moment, he says:

According to Asclepiades, however, nothing is naturally in sympathy with anything else, all substance being divided and broken up into inharmonious elements and absurd “molecules.”

Now, you may remember from Scott’s review of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions that part of Descartes’ claim to fame is inventing the idea of a purely materialist world, where matter interacts with other matter directly, with no recourse to hidden “forces” or “essences” — the classic billiard balls or clockwork universe. This is part of why Newton’s theory of gravity caused such an uproar. Saying that it is in the nature of all matter to attract other matter sounded uncomfortably essentialist! Only Newton’s constant defense and the inherent strength of the theory eventually managed to win it acceptance.

It’s easy to imagine that Galen was a target of the Cartesian revolution in the same way that Aristotle was. As far as I know, Aristotle never explicitly argued against atomism, just in favor of essentialism. While Galen was prolific, his work still wasn’t as broad or as foundational as Aristotle’s. These factors might have left Galen more open to criticism. While grudging respect for Aristotle continued, it might have been enough to discredit Galen in the mind of most scholars.

It’s hard to make the timeline line up for this version of the story, however. Vesalius was arguing against Galen’s anatomical texts in the 1530’s and 1540’s, and Francis Bacon criticized him so roundly in 1605. Yet bloodletting was endorsed by major medical organizations as late as the 1830s, and during these decades France and England were still importing (!) millions of leeches a year. Possibly the criticism of Galen has always been stronger in scientific than in medical circles. In fact, my experience with modern pieces written about Galen is that those from a scientific perspective are full of criticism, while those of a more strictly medical background tend to mention his discoveries and the treatments he pioneered.

Whatever the cause of this hit job was, it seems to have been unjustified. Galen doesn’t seem like a very nice or pleasant guy to be around, but he was an empiricist if ever there was one, and he was trying to understand biology with absolutely every tool available to him at the time, so he could provide the best treatment possible. He was wrong about humorism, but after reading this book, it’s more understandable how at the time, humorism might have seemed like the best theory around. If more of us were like Galen (minus all the vivisection), we would be much better off.