Your Book Review: Public Choice Theory And The Illusion Of Grand Strategy

[This is one of the finalists in the 2022 book review contest. It’s not by me - it’s by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done, to prevent their identity from influencing your decisions. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked - SA]

[update 6/26: at least one paragraph of this review appears to be plagiarized; seehere for more information. I will be investigating this and possibly disqualifying it from the contest -SA]

Introduction

[In Public Choice Theory And The Illusion Of Grand Strategy], Richard Hanania details how a public choice model (imported from public choice theory in economics) can explain the United State’s incoherent foreign policy much better than the unitary actor model (imported from rational choice theory in economics) that underlies the illusion of American grand strategy in international relations (IR), in particular the dominant school of realism. As the subtitle How Generals, Weapons Manufacturers, and Foreign Governments Shape American Foreign Policy suggests, American foreign policy is driven by special interest groups, which results in millions of deaths for no good reason.

In the unitary actor model, the primary unit of analysis of inter-state relations is the state as a monolithic agent capable of making rational decisions (forming coherent, long-term “grand strategy”) from cost-benefit analysis based on preference ranking and expected “national interest” maximisation.

In the public choice model, small special-interest groups that reap a large proportion of the benefits from a policy (concentrated interests) are much more incentivised to lobby for a policy than the general public who pay for a negligible portion of the cost of the policy (diffused interests) are incentivised to lobby against. The former can coordinate much easier than the latter that has to overcome rational ignorance (the cost of educating oneself about foreign policy outweighs any benefit an one can expect to gain as individual citizens cannot affect foreign policy) and the society-wide collective action problem (irrational for every citizen to cooperate in the prisoner’s dilemma especially if individual gain is negligible) resulting in inefficient (not-public-good-maximising) policymaking i.e. government failure.

It is very much an academic book that should revolutionise the whole field of IR by challenging the fundamental assumption of realpolitik with impressive rigour, so the brisk 200 pages should probably be mandatory reading for IR/political science freshmen. Like Robin Hanson, I would have been persuaded by an article length analysis, but as Hanania himself agrees, the belabouring book length treatment is to disabuse academics who by nature demand sweat and impressive mastery of literatures — this review should, dare I say, suffice for the cynical reader.

1. Goodbye Unitary Actor Model

IR theorists have put forth three justifications for the unitary actor model.

First, Morgenthau argued that human nature is intrinsically aggressive, so states seek to dominate one another in the struggle for power. But this begs the question of why the collective action problem inherent to large-scale cooperation within hierarchic political organisation is overcome at the level of states.

Second, Mearsheimer, Bosen, and Waltz argued that nationalism is strong enough to make states act like unitary actors. However, nationalism only appears strong when compared to the pull of universalist ideologies like Marxism or liberalism, because soldiers can continue fighting for their fellow combatants despite widespread disillusionment with the mission itself as seen in the Iraq war. Nationalism is weaker than financial self-interest, as no viable army can exist without paying soldiers market salary, and states need laws like tariffs to protect domestic industry; nationalism is also weaker than familial interests, as states need laws against nepotism.

Third, Waltz argued that states behave as unitary actors because those that do not get overtaken by those that do. The Darwinian or market selection analogy breaks down as there are only very few states at any point in history i.e. insufficient units for selection, and conquest has disappeared from international society i.e. selection pressure does not exist.

Other IR theorists have argued that the unitary executive model can save the unitary actor model but Hanania argues that they, too, fall short.

First, Milner and Tingley argued that US presidents are more constrained in policy areas with concentrated interests (e.g. trade, foreign aid, immigration), and less constrained in policy areas with diffused interests i.e. public goods (e.g. geopolitical aid, deployment of force, sanctions), so American foreign policy has the tendency to militarise. Alas, voters have short memories — an election with the president’s party on the ballot is never more than two years away, so the president should constantly be seeking to help his own party, even when not facing the voters himself. A “grand strategy” based on a biennial election calendar is not much of a grand strategy at all.

Second, Posner and Vermeule argued that the executive branch of the US government can be considered a united force capable of outmanoeuvring a Congress divided by power, which leads to a federal government that is more responsive to public opinion via elections and politics (rather than laws) to better solve problems. Afterall, politicians are political — they are selected based on their ability to convince others of their sincerity, likability, and competence, not necessarily their ability to solve problems, and especially not to solve problems that will arise after they have left office.

2. Hello Public Choice Model

Public choice theory was developed to understand domestic politics, but Hanania argues that public choice is actually even more useful in understanding foreign policy.

First, national defence is “the quintessential public good” in that the taxpayers who pay for “national security” compose a diffuse interest group, while those who profit from it form concentrated interests. This calls into question the assumption that American national security is directly proportional to its military spending (America spends more on defence than most of the rest of the world combined).

Second, the public is ignorant of foreign affairs, so those who control the flow of information have excess influence. Even politicians and bureaucrats are ignorant, for example most(!) counterterrorism officials — the chief of the FBI’s national security branch and a seven-term congressman then serving as the vice chairman of a House intelligence subcommittee, did not know the difference between Sunnis and Shiites. The same favoured interests exert influence at all levels of society, including at the top, for example intelligence agencies are discounted if they contradict what leaders think they know through personal contacts and publicly available material, as was the case in the run-up to the Iraq War.

Third, unlike policy areas like education, it is legitimate for governments to declare certain foreign affairs information to be classified i.e. the public has no right to know. Top officials leaking classified information to the press is normal practice, so they can be extremely selective in manipulating public knowledge.

Fourth, it’s difficult to know who possesses genuine expertise, so foreign policy discourse is prone to capture by special interests. History runs only once — the cause and effect in foreign policy are hard to generalise into measurable forecasts; as demonstrated by Tetlock’s superforecasters, geopolitical experts are worse than informed laymen at predicting world events. Unlike those who have fought the tobacco companies that denied the harms of smoking, or oil companies that denied global warming, the opponents of interventionists may never be able to muster evidence clear enough to win against those in power with special interests backing.

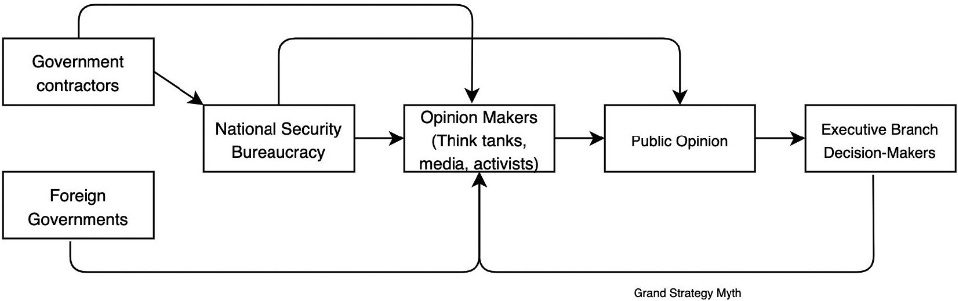

Hanania’s special interest groups are the usual suspects: government contractors (weapons manufacturers [1]), the national security establishment (the Pentagon [2]), and foreign governments [3] (not limited to electoral intervention).

What doesn’t have comparable influence is business interests as argued by IR theorists. Unlike weapons manufacturers, other business interests have to overcome the collective action problem, especially when some businesses benefit from protectionism. By interfering in a foreign state, the US may build a stable capitalist system propitious for multinationals, but can conversely cause a greater degree of instability and make it impossible to do business there; when business interests are unsure what the impact of a foreign policy will be for their bottom line, they should be more likely to focus their lobbying efforts elsewhere.

The mechanism of influence is outbidding all other competitors in the marketplace of ideas, by

-

donating to the most influential think tanks in Washington (the United Arab Emirates to CSIS; Qatar to Brookings Institution);

-

funding movements, as in the case of neoconservatives who pushed for Saddam’s overthrow, the movement was spearheaded by PNAC (created by Lockheed Martin) lobbyists who would go on to become Bush administration officials like Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Cheney and Weber;

-

bureaucratising public opinion management (the supposedly independent and neutral RAND Corporation gets 80% of its funding from the federal government);

-

boxing in the president’s major foreign policy decision via military generals’ press manipulation (MacArthur commenting on escalating engagement in the Korean War before he was fired by Truman; top generals in the Obama administration publicly discussing troop commitment needed to win in Afghanistan)

-

shaping foreign policy reporting from propagandistic journalists in the close-knit ‘foreign policy community’ (former Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland is literally the wife of neocon author Robert Kagan)

-

‘revolving doors’ for all three concentrated interest to actively collaborate (80% of retired three- and four-star generals between 2004 and 2008 went on to work as consultants or executives in the defence industry; ‘rent-a-general’ like the Four Star Group in which generals leverage their Pentagon contacts to consult in equity investing)

You know the book is dry when this is one of the only two graphics.

3. Team America: World Police

Hanania argues that Ikenberry and other’s advocacy of America’s role in maintaining the “rules based international order” cannot account for the American exceptionalism in blatantly violating international law — 237 American military interventions between 1950 and 2017 (3.5 per year), and 64 covert regime changes in the Cold War alone.

In the satire, the terrorists have WMDs courtesy of Kim Jong Un; in real life, Saddam had neither WMDs nor terrorist ties.

In the satire, the terrorists have WMDs courtesy of Kim Jong Un; in real life, Saddam had neither WMDs nor terrorist ties.

International law allows the use of force either in self-defence or with the approval of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). The “legal” American military interventions include:

-

The Korean War(1950-1953): UNSC declared a “breach of the peace” when North Korea crossed the 38th parallel

-

The Vietnam War(1954-1975): from the initial American involvement in fighting off communist insurgency in the South as requested by the sovereign state of the Republic of Vietnam, to the later ceding of governing responsibilities to South Vietnam with the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement in 1975 (notwithstanding the violation of proportionality in the Vietnam War, and the violation of international law in extending conflict to the sovereign nations of Cambodia and Laos)

-

The First Gulf War (1990-1991): UNSC authorised the US and 34 other countries to bomb Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi invation out of Kuwait at the Gulf Monarchy’s request

-

The War in Afghanistan (2001-2021): a series of UN Resolutions justified, out of self-defence, the US invasion of Afghanistan, overthrow of the Taliban government, and targeting of al-Qaeda, in spite of the failure of nation building when the Taliban returned to Kabul in the midst of the final American withdrawal

Similarly, the Soviet Union did not violate the sovereignty of states when it invaded Afghanistan at the invitation of its government in 1979, and similarly in Syria in 2015. When Russia violated international law, most notably Georgia in 2014 and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the goal was occupation rather than removing their governments, killing their leaders, or fundamentally remaking their societies (the book was published before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine).

The US is truly singular in violating international law:

-

Grenada Intervention (1983): Reagan ordered an invasion, not out of self-defence nor with UNSC approval (in fact voted against by UN general assembly 108 to 9), of the small island off the coast of Venezuela where its communist military junta came into power

-

Yugoslavia Humanitarian Intervention (1995, 1999): UNSC sanctioned NATO’s intervention against ethnic Serbs’ massacre of ethnic Bosnians in Srebrenica and Sarajevo in 1995, but not the so-called “illegal but legitimate” 1999 bombing of Kosovo to stop the Serbs’ ethnic cleansing of Bosnians as NATO would have been vetoed by Russia and China.

-

The War in Iraq (2003-2011): China, Russia, France, and Germany all opposed the invasion of Iraq and overthrow of the Saddam regime that was sold as a ‘preemptive war’, turns out there were no WMD and the supposed connection between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda was nonexistent.

-

The bombing of Librya(2011): a newly passed UNSC resolution allowed NATO to enforce a no-fly zone against al-Gadhaffi’s government “to protect civilians”, but did not sanction the no-fly zone intended for regime change, nor the subsequent airstrike that led to the capture and killling of al-Gadhaffi by rebels

Indeed, the idea of some wars being “illegal” seems odd enough, but the fact that no country on earth violates the most fundamental tenets of international norms so flagrantly and often as the United States means that IR theorists cannot insist on the grand strategy of maintaining “rules based international order”.

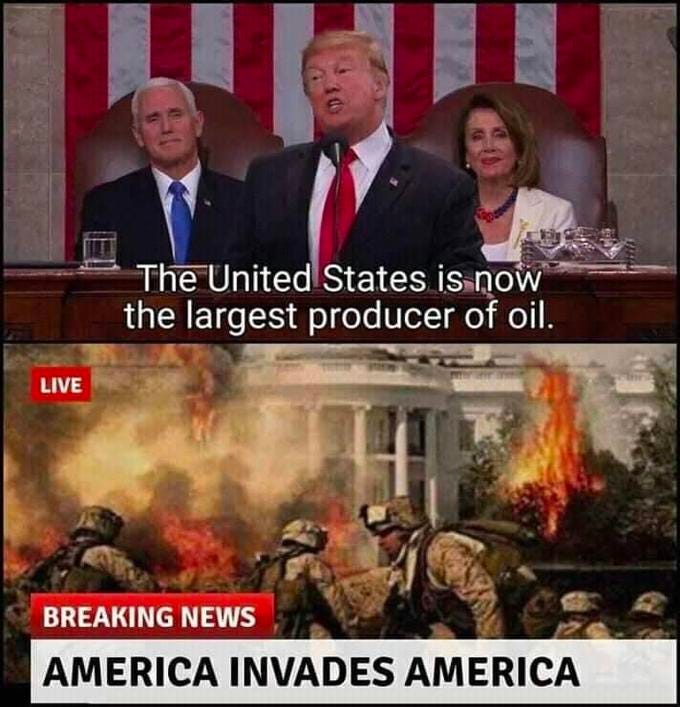

Hanania also dismisses other popular explanations of American grand strategy, in particular Chomsky’s argument that America’s interventions are a matter of great power competition and/or a struggle for resources. Somalia and Yugoslavia are some of the least strategically important states in the 1990s; the war in Iraq did not in any way increase American power but rather empowered Iran; and the removal of al-Gadhaffi made it clear to Kim Jong Un that any leader willing to dismantle their WMD program and ally themselves with the US in the war on terror were destined to be killed. As for intervention in oil-rich states, the US was not even willing or able to ensure American corporations benefited as Libya was already selling its oil on the open market (al-Gadhaffi’s removal only hurt production), and the largest Iraqi oil contracts under US occupation went to China and Russia (even if they went to the US, the costs of war ~$3 trillion was far from recoverable).

It’s surprising how the longest-running meme of American invasion for oil is misplaced cynicism; US foreign policy elites aren’t even competent enough to secure oil for American exploitation.

It’s surprising how the longest-running meme of American invasion for oil is misplaced cynicism; US foreign policy elites aren’t even competent enough to secure oil for American exploitation.

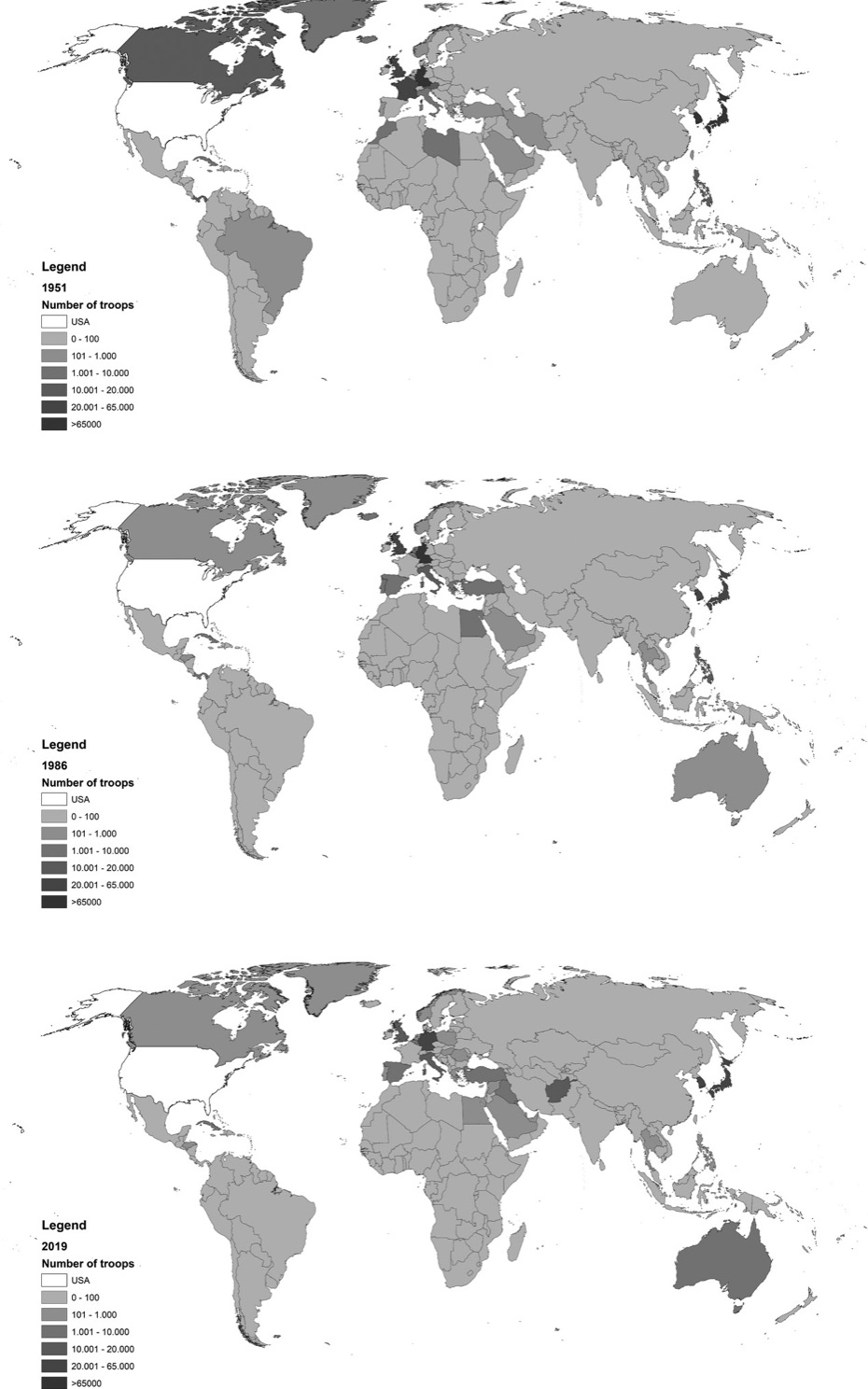

An additional evidence against American grand strategy is the pattern of troop deployments abroad:

Practically unchanged throughout 1951, 1986, and 2019.

Practically unchanged throughout 1951, 1986, and 2019.

It’s difficult to see what threat the US is protecting against in the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany. The rise of China has not lead to increase in troop deployment in Japan or South Korea; the wars in the Greater Middle East has not resulted in the influx of the bulk of troops from the former Axis powers; the fall of the Soviet Union has not seen any withdrawal as promised to Gorbachev but rather expansion of troops right up to the border of the Russian Federation. Once again, Hanania clearly shows that status quo bias has been disguised as grand strategy.

IR theorists have long debated what strategy the US should adopt when responding to potential challengers: realists are pessimistic in viewing great powers to be destined for war; liberal internationalists are optimistic in trusting the pacifying effects of trade and enlightened self interests. Either way, they assume states make rational decisions to attain long-term objectives, but the two ideologically hostile states of the Soviet Union and China show that presidents are too worried about short-term political prospects to stop American business and technology from engaging with and empowering rivals. If there is no grand strategy against the most powerful geopolitical rivals, it’s unlikely any exists for lesser adversaries.

4. The Atrocity Of American Sanctions

Sanctions were introduced by the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) in 1977 gave the president the right to sign an executive order to declare a national emergency to prohibit any transaction between anyone under the jurisdiction of the United States and the foreign country or its nationals. This means most sanctions are decided on and applied within the executive branch with little input from Congress or the broader public.

The three main concentrated interests do not oppose sanctions (the only exception being the unprecedented lobbying campaign from American businesses to open up trade with China). The national security bureaucracy doesn’t stand to gain or lose from trading with foreign states, nor do government contractors (most rogue states’ economies are miniscule compared to China’s). Foreign governments that are candidates for sanctions also can’t oppose them — Kim Jong Un cannot fund Washington think tanks; Israel and Saudi Arabia can fund a maximum pressure campaign against Iran as even meetings with Iranian state officials bring accusations of illegality.

In theory, sanctions work by:

-

Hurting the economy

-

People get fed up

-

Blame the regime for their problems

-

Get rid of the regime

The theory falls apart because citizens still need to overcome the collective action problem; regime elites, almost by definition, benefit from the current regime; regimes prioritise paying for security forces over domestic population; and rival powers come to the rescue.

As empirical research clearly shows, sanctions are the most brutal and harmful when they have the least likelihood of success. Step 1 of causing economic hardship certainly succeeds — UN sanctions were associated with an aggregate GDP reduction 25% of GDP per decade; US sanctions were associated with a 13.4% decline over seven years. Beyond the destruction of wealth of innocent citizens, sanctions cause excess deaths due to starvation and brutalising ever more desperate regimes that engage in mass killing to repress domestic protests — six-figure infant deaths in Iraq; 1,000 infant deaths per month in Haiti, 40,000 excess deaths in Venezuela in 2017-2018 alone; 38% of Syrian population unable to meet basic food requirements in 2018.

Step 4 of regime change has yet to happen as a result of the harshest sanctions against Cuba since 1959, Iraq since 1998, Syria since 2011, and Venezuela since 2019. The Bush, Clinton, new Bush, and Obama administrations all stuck to a policy of not speaking with adversaries, which is the opposite of achieving foreign policy goals by providing targeted regimes a clear path towards the removal of sanctions.

Once again, Hanania shows that there is no American grand strategy — sanctions are used to accomplish domestic political goals rather than foreign policy objectives. Leaders face domestic pressure to ‘do something’ about human rights violations and military aggressions abroad, and short of military intervention, sanctions is the only option beyond words of condemnation. Sanctions are an ‘easy’ option because there will be little to no domestic opposition when all the deaths and economic destruction are out of sight; out of mind.

5. The War On Terror

The Bush Years

After 9/11, the United States has invaded the al-Qaeda sanctuary of Afghanistan, but also the completely irrelevant Iraq. In the view of grand strategy, war is a means to accomplish national security objectives; in the view of public choice, national security objectives is a means to accomplish war (or at least a large military budget). The post hoc rationalisation of the war on terror rests on three incoherent ideologies:

-

Antiterrorism: disproportional militarised response to terrorist attacks

-

The Freedom Agenda: America must spread democracy abroad

-

Counterinsurgency (COIN)

In the case of Afghanistan, the Bush administration was so eager to go to war it avoided any other options. No evidence has ever emerged that Taliban (the political faction that ruled Afghanistan at the time) itself knew about the 9/11 attacks, much less planned it; the Afghan ambassador to Pakistan condemned the attacks on 9/12. “We don’t negotiate with terrorists” became the standard American line — before the war began, Taliban was willing to discuss bin Laden’s fate but the White House Chief of Staff refused; after the war began, Taliban was willing to hand over bin Laden to a third country for trial but White House refused just the same.

In the case of Iraq, Bush was so eager to, in his own words, “Fuck Saddam, We’re taking him out” as early as February 2002 (and floated the idea of invading Iraq to Tony Blair), that on 9/17 Bush told his cabinet “I believe Iraq was involved, but I’m not gong to strike them now. I don’t have the evidence at this point.” The administration couldn’t find any evidence directly tying Saddam to 9/11, so they settled on the now-discredited lies of WMDs and “ties” between al-Qaeda and Iraq. “We don’t negotiate with terrorist”’ extended to the non-terrorist Saddam — before the war, Saddam was cooperating with the International Atomic Energy Agency; after the war began, Saddam was willing to accede to practically all Amercan demands but White House refused communication just the same. Just like in Afghanistan, the Bush administration had no interest in exploring any other option short of war.

Two feuding factions within the Bush administration had little contact with each other: the war hawks (neocons like Cheney i.e. products of Lockheed Martin), supported by the Pentagon, did not want to do nation-building; those partial to nation-building (the State Department) did not want war. Bush agreed with the former at the start of the war, but once Saddam was removed, sided with the latter. The postwar plan for Afghanistan was officially determined by the Bonn Agreement of 2001, but neither Bush nor Cheney consider it to be worthy of much thought in their memoirs despite years of hindsight; the postwar plan for Iraq lay entirely in the hands of Paul Bremer as subsequent Deputy Committee meetings on Iraq stopped being conducted — there wasn’t a single meeting to discuss disbanding the Iraqi army that left 400,000 jobless former soldiers prime for insurgency.

The Iraq war dealt with no real crisis but cost the US trillions of dollars and thousands of lives, plunged Iraq into two decades of intermittent civil war — a candidate for the worst American foreign policy failure in history, but a success for the careers of Bush (who won reelection and congressional seats) and his advisors who led the US into Baghdad (who went on to work for think tanks, the World Bank, and the Trump Administration). Once again, there is no grand strategy as each party was only self-interested in short-term gains.

The Earlier Obama Years

As a candidate, Obama campaigned in support of the Afghanistan war, and indeed his first foreign policy decision as president was to send thousands of additional troops to Afghanistan, largely due to overwhelming political pressure from top generals like Petraeus and McChrystal who boxed Obama into sending more troops by limiting the options presented to Obama, blatantly lobbying in press interviews, and threatening dire consequences like resigning from commanding troops in Afghanistan. We know Obama was hesitant as he announced at the same time that American troops would begin withdrawal in July 2011 (by 2015 he announced that American troop presence would stay in Afghanistan indefinitely).

Obama’s second decision was to bomb al-Qadhafi in the name of Libyan regime change, due to domestic but this time also international political pressure from the heads of France and the UK who would face political embarrassment if Qadhafi’s regime, despite months of bombing and sanctions by the US-led coalition, recaptures the rebel-held Benghazi. NATO forces bombed al-Qadhafi’s convoy. Ten days after the killing of the dictator, the bombing campaign ended, and the subsequent decade of intermittent civil war faded from the American consciousnesss.

Obama’s third decision was to cripple Assad’s regime in Syria with sanctions and by arming and training rebels, again due to overwhelming political pressure from hawkish ‘foreign policy community’ who still criticise Obama for having ‘done nothing’ despite spending $1 billion through the CIA and $500 million through the Pentagon, and crushing the Syrian economy. Top officials in the Obama administration admitted that assisting rebels would not change the course of war, nor was there any way to prevent arms from ending up in the hands of ISIS and al-Qaeda. Indeed, the Syrian civil war only got bloodier with American involvement.

The Later Obama Years

Obama’s first major decision was the war on ISIS with the reentry into Iraq from which all American troops withdrew just a few years ago in 2011, due to overwhelming political pressure and in the face of a potentially humanitarian catastrophe (ISIS was going to massacre the Yazidi religious sectarians in Mount Sinjar). This time, the United States would roll back all territorial gains of the Islamic State by working with the Iraqi government, Shia militias in Iraq, and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces.

Obama’s second decision was signing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Acton (JCPOA) with Iran to stop its nuclear weapons programme in exchange for UN and EU sanctions to be lifted, $100 billion in assets seized by the US to be returned to Iran, and the US to stop implementing secondary or third-party sanctions. This time, Obama faced unusually significant pressure from Congress which passed the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act by overwhelming majority to be able to revoke JCPOA, but Obama signed JCPOA with Iran nonetheless as enough Democrats would be able to sustain a veto. This was the one and only decision that made sense from the perspective of classical IR theory — American leaders doing things they think are right for the country without a clear political payoff. Indeed, the Iranian nuclear agreement is the exception that proves the rule of public choice, as the deal was only possible near the end of Obama’s second term, and at the end cancelled by Trump upon entering office — a president’s foreign policy accomplishment made without the support of concentrated interests only lasted as long as his administration.

6. Learning From American Foreign Policy Failures

IR theorists widely acknowledge that it was a mistake to invade Vietnam and Iraq, and even the war in Afghanistan went on for too long even if it was originally justified, but these scholars have yet to comprehend the shortcoming of the unitary actor model in accounting for the lack of rational cost-benefit analysis. Comparing the pre-invasion GDP of the countries to what the US has sacrificed (even setting aside the number of lives lost), the GDP-to-money-spent ratio has been 1:74 in South Vietnam, 1:43.3 in Iraq, and a staggering 1:396 in Afghanistan. In other words, the United States has spent in Afghanistan the equivalent of that country’s level of production for close to four centuries.

Cost-benefit analysis also fails outside the major wars: NATO, despite the collapse of the USSR, is willing to absorb practically any country including states that can drag the US into war without contributing anything to American security; the military expenditure in Japan and South Korea, despite anti-China talks in Washington, are either flat or declining.

While an utter failure in humanitarian and economic terms, American foreign policy has a been a resounding “success” from the public choice perspective:

-

Lockheed Martin received $36 billion in government contracts in 2008 alone (more than any company in history)

-

The Pentagon has a budget of $700 billion for fiscal year 2019 (higher than it was at the end of the cold war even after adjusting for inflation); the vast majority of high-ranking generals have become rich as consultants or weapons industry executives upon retirement

-

Eastern European countries that joined NATO are protected by the threat of American nuclear war; Israel and Middle Eastern Gulf monarchies see an Iran impeded by American sanctions

Hanania ends with some ideas for legal reforms:

-

Limited, if not lifetime, ban of retired military and national security personnel from taking jobs with Pentagon-contracted companies

-

Requiring think tanks to disclose their funding sources like 501(c)(3) non-profits

-

Closing the loophole for scholarly work (e.g. authoring books) in the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) that requires individuals lobbying for foreign states to report their propaganda to the federal government

-

Making lobbying illegal for all states including allies (e.g. Saudi Arabia), not just enemies (e.g. Iran), except recognised democracies

-

Reinforcing the Supreme Court ruling in New York Times Co. v. United States by prosecuting any individual who publicises classified material, including top military officials and journalists who routinely leak classified material but are never prosecuted (unlike whistleblowers like Edward Snowden)

And finally some ideas for norm changes:

-

The press should include current weapons industry employment when reporting ex-government officials

-

The press should include funding information when reporting think tank scholars’ work, and clarify that the organisation cited refused to provide said information should it be unavailable

-

The press should include political motivations when reporting American leaders’ foreign policy decisions (as they do for Kim and Putin)

-

The press should include Tetlock’s superforecasting/prediction markets when reporting the forecasts by the military and national security bureaucracy at public interviews, official reports, and congressional testimony

7. Conclusion And Further Readings

Gordon Tullock, one of the founding fathers of public choice theory who coined “rent-seeking”, has always wished for a book like this, and now it exists. It is clear to me that Hanania’s public choice model should usurp the conventional unitary actor model, and any scholar who insists on American grand strategy is deluding themselves.

The book hasn’t been reviewed by mainstream outlets (which probably only reviews “pop” nonfiction), but have been unanimously praised by scholars in adjacent fields: Steven Pinker praised it as “cynical but probably accurate”; Robin Hanson was “quite impressed”, Byran Caplan, whose work The Myth of the Rational Voter _was cited extensively by Hanania, praised it as “eye-opening”; Tyler Cowen praised the book as impressive in spite of finding Hanania’s view to be more sceptical than his own — a sentiment I share after reading about the East Asian economic miracle (the greatest anti-poverty program in history) facilitated by American intervention in _How Asia Works (another contrarian economics-related work I’ve reviewed).

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

At the time of writing, Russia is invading Ukraine, so it is interesting to see how well the public choice model’s predictions fit. Indeed, the unitary actor model can describe autocratic states to some degree — to understand Russia we only have to get into the head of Putin (the model still falls short in accounting for the oligarchs who run the mafia state). Ukraine is central to Putin’s ideology and subjectively important to Russian society, and the desire to obliterate and absorb the nation of Ukraine far predates the history of NATO (see also Adam Tooze’s excellent essay on understanding Russia as a strategic petrostate). As Hanania writes on his Substack (worthy of your subscription, by the way)4:

We know what the Russians want. They have made clear, openly and consistently, that they do not want NATO to keep expanding. When it became apparent in December that an invasion was on the table, the US started a diplomatic process that has involved trying to work out concessions on other things, while refusing to take NATO membership for Ukraine off the table.

Putin has become Satan in liberal imagination, and when it comes to the culture war, the emotional response is overwhelming. Hanania writes:

Brexit, Trump, and the rise of Orban and other right-wing populists in Europe have helped solidify a narrative in which Russian hackers and influence operations are behind everything liberal elites find distasteful, from opposition to Syrian refugees to bans on Critical Race Theory. Here’s a website laying out all the things Russia has been accused of “weaponizing” in the media, including dolphins, federalism, and the weather. The details of debates surrounding the wisdom of NATO expansion and whether Ukraine actually matters to the United States are lost in the larger story, as emotional denunciations of Putin as the source of all anti-democratic activity drives attitudes and policies. Inconvenient facts are ignored because it’s not really about “democracy,” “international law,” or any of the other words they use to obscure the fact that it’s culture wars all the way down.

And the Western response is driven by extreme public outcry to an unprecedented extent:

It’s all a competition to see who can signal “I hate Putin” the most, but Germany was still shutting down all its nuclear power plants to rely on Russian gas despite warnings from every other EU state (Russia accounts for 40% of Europe’s gas imports) — so much for grand strategy.

It’s all a competition to see who can signal “I hate Putin” the most, but Germany was still shutting down all its nuclear power plants to rely on Russian gas despite warnings from every other EU state (Russia accounts for 40% of Europe’s gas imports) — so much for grand strategy.

That is not to excuse Putin’s invasion (he is, after all, the aggressor) and no, Ukraine is not “the West’s fault” as Mearsheimer has claimed in his viral lecture, but “NATO’s door remains open” for me and “we’re going to start WW3 because you’re in my sphere of influence” for thee is no grand strategy at all. Indeed, the irrational Western response is not predictable by the unitary actor model, but by the public choice model. Hanania writes:

If you were going to cut Russia off from SWIFT, for example, why wouldn’t you announce it beforehand? The whole point of a punishment like that is supposed to be its deterrent effect, but if you don’t communicate that a specific action will happen, then it can’t influence behaviour. The answer here seems to be a lack of grand strategy, with leaders responding to events according to emotion and public relations more than anything. Cutting off SWIFT, or even threatening to do so, seems extreme before an invasion occurs, but not after it has begun.

The West cannot rely on sanctions to make Russia abandon its core national security interests, which at the very least include a no-NATO commitment, the acceptance of the secession of Donetsk and Luhansk, and the recognition of the annexation of Crimea. Sanctions will also push Putin closer to Beijing, and the US will continue down the self-defeating path of alienating both of the other two superpowers — so much for American grand strategy. Hanania writes:

Even if Putin has maximalist aims at this point, that doesn’t mean sanctions are worth doing. Their costs are high and they may have major consequences for the global economy. One has to consider the possibility that they make Russia more repressive at home and more brutal in its persecution of the war.

Putin is getting sanctioned, but ordinary Russians are getting cancelled. The Metropolitan Opera of New York has announced it will no longer stage performers who have supported Russian President Vladimir Putin. Carnegie Hall has done the same, and the Royal Opera House in London is cancelling a planned Bolshoi Ballet residency (one of the oldest and most prestigious ballet companies in the world). Eurovision banned Russia. Tchaikovsky is cancelled. As Tyler Cowen writes, cancel culture against Russians is the new McCarthyism.

The culture war has morphed into a hyperreal form on the Internet. Just as COVID is the first pandemic in the Age of Twitter, so the Ukraine invasion is, in some sense, the first war in the Age of Twitter. As it unfolds, we are seeing many disturbing parallels to the events of early 2020. People are rapidly normalising once-fringe ideas like a NATO-enforced no-fly zone (while completely oblivious to the fact that it means shooting down Russian planes and causing WW3), direct US conflict with Russia, regime change in Moscow, and even, incredibly, the use of nuclear weapons. The overnight flips on German defence spending and SWIFT are like the overturning of conventional public health policies on masking and lockdowns. We have entered the age of shitpost diplomacy, as coined by Tanner Green, in which the official Twitter account of the US Embassy in Kiev literally posts memes to spite Putin:

A Russian sixth-grader could explain why celebrating the glories of Kievan Rus does not subvert Putin’s claims about the history of the Russian nation so much as reinforce them.

A Russian sixth-grader could explain why celebrating the glories of Kievan Rus does not subvert Putin’s claims about the history of the Russian nation so much as reinforce them.

Just like Hong Kong’s protests, Ukraine has won the meme war with utterly lopsided propaganda and unanimous international support on the Internet. As Yoshimi writes:

Floating ghostlike above it is our war, the myth of the ‘Ghost of Kyiv’, ace MIG-29 pilot who has apparently shot down six Russian planes, or the legend of the Ukrainian soldiers defending an island outpost who replied “Russian warship go fuck yourselves” to a surrender offer and may or may not have died heroically, or two Russian II-76 transport aircraft that maybe were shot down near Kiev, or videos of air strikes or dead bodies which variously are Russian or Ukrainian until they turn out to be from Gaza six years ago, or the viral video of an old Ukrainian woman telling off a Russian soldier by offering him sunflower seeds so when he dies, sunflowers (Ukraine’s national flowers) will sprout from the soil. We’re raising funds for the Ukrainian army on crowdfunding apps and giving advice to the civilians being handed assault weapons about how to disable tanks, sharing weird homophobic pictures of Putin as a gay icon and spamming Russian government posts. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky has made the decision to stay and fight rather than flee like most would-be leaders who go all in for American foreign policy, and now is being deified by us as “badass”, “a true leader”, etc. etc., alongside his people, whose resistance to authoritarianism we are told is unparalleled in the modern world. After all, so it goes, who could be next?

And like in Hong Kong, despite winning the culture war in hyperreality, the actual war in reality is won by the side with overwhelming military might, not morality. The real war is where Ukrainians are experiencing the genuine life-shattering effects of military conflict. It matters because this is the first time Western response is driven by Twitter outcry, and it will not be the last.

A New EA Cause?

Besides Hanania’s recommendations in the last section (which he admits are more or less impossible in an excellent interview with Caplan), a worthy EA priority might be to somehow turn the public tide on sanctions, which literally kill more people than Putin. Americans should be appalled by the atrocity committed in their names. The banality of the incompetence of foreign policy elites does not excuse their evil. With how entrenched the special interests are, I have no idea if it’s even worth trying, but at the very least the sheer amount of suffering and death from sanctions should be made common knowledge.

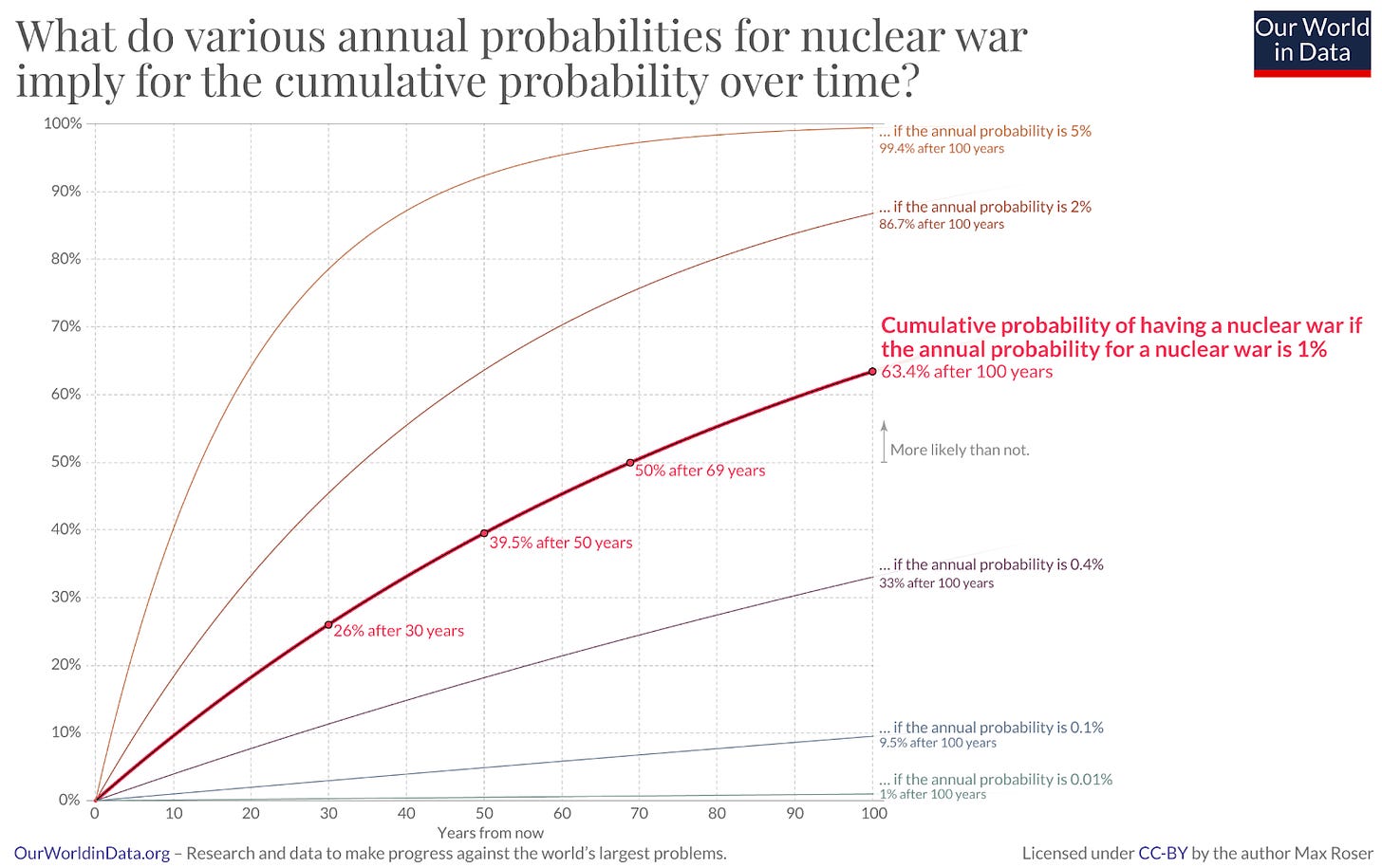

Nuclear security is one of the top priorities in Effective Altruism, per 80,000 Hours, Future of Life Institute, and Our World In Data. Toby Orb, who wrote the definitive book on existential risk, The Precipice , estimates x-risk from nuclear war to be ~1 in 1000 in the next century. Luisa Rodriguez estimates a 1.1% chance of nuclear war each year and that the chances of a US-Russia nuclear war may be in the ballpark of 0.38% per year; summarised by Max Roser as:

Nuclear risk is neglected by the public because of [Pax Americana](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pax_Americana#:~:text=Pax%20Americana%20(Latin%20for%20%22American,United%20States%20became%20the%20world’s) since the collapse of the USSR, and is not discussed as often in EA as it’s thought to be relatively well-funded and mainstream, but in fact major donors like the MacArthur Foundation have been withdrawing funding. As Joan Rohling details in an 80,000 Hours podcast there is much to be done, especially when Ukraine gave up their nuclear arsenal in 1994 in exchange for Russia’s promise to never threaten or use military force against them.

A worthwhile adjacent cause area might be de-escalation of public outcry to reduce x-risk from nuclear war beyond just regular anti-proliferation efforts — even a Russian specialist from the RAND Corporation is surprised by how much public outrage is driving policy:

Even just the pace of the sanctions: we went to 11 out of 10 in like two days — farther than many expected we’d ever get in short order. And I think the same is true about these military assistance initiatives. We’re just trying to do something because there’s a public demand for action. So that’s what worries me, that the sort of public outrage that’s being channeled in Western democracies through political systems could result in decisions that prove ultimately unwise.

Despite how odd it is that some wars are “legal” while others aren’t, we should be glad UNSC exists as much as everyone laughs at how useless the rest of the UN is. All is fair in love and war, but international norms is all that stands between us and nuclear annihilation. It is hard to emphasise just how delusional it is for the public to fixate on no-fly zones — I, like Scott, am surprised we’re still capable of jingoism.

80,000 Hours has updated their top career recommendations to include China specialist to improve China-Western coordination on global catastrophic risk, which seems more important after reading how irrational and captured the American foreign policy apparatus is. As Hanania writes, “great power competition” is an anachronism. If Ukraine is the first war warped by hyperreality, it won’t be the last. Now that US foreign policy elites have driven Putin into the arms of China, let’s hope IR specialists can imbibe the public choice model instead of antagonising yet another nuclear rival.

Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy is an important work because it raises the sanity waterline, which at the least should make us stop killing millions for no reason, and at the most should make the human race more knowledgeable of how to prevent total extinction from nuclear armageddon. Pax Americana is dead, but a multipolar world will be more humane.

Endnotes

-

In the fiscal year 2018, the top five government contractors were all weapons manufacturers, with Lockheed Martin in first place at $40.6 billion. The Department of Defence spent $358 billion on contracting, ten times higher than second place Department of Energy. Collective action problems that stop a bunch of smaller companies from effectively influencing policy are no hindrance for companies like Lockheed Martin.

-

It is a universal feature of the American government that substantial federal agencies do not shrink — even Ronald Reagan, the president most opposed to an expansive federal government since Coolidge, failed to see any reduction in spending.

-

Foreign governments can be direct beneficiaries of American foreign policy as the US defends and overthrows countries, and provides material and economic aid; indirectly the US controls American weapons sales, aid, and diplomatic support for states to head off domestic rivals. Dictatorships, in particular, act more like unitary actors as their existential question relies on their ruling territories, not elections.

-

Pax Americana had been so strong that even American ice-cream companies have foriegn policy priorities — Ben & Jerry’s thinks NATO should chill a little over Ukraine.