Your Book Review: Safe Enough?

[This is one of the finalists in the 2023 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

The date is June 9, 1985. The place is the Davis-Besse nuclear plant near Toledo, Ohio. It is just after 1:35 am, and the plant has a small malfunction: “As the assistant supervisor entered the control room, he saw that one of the main feedwater pumps had tripped offline.” But instead of stabilizing, one safety system after another failed to engage.

Over the next twenty minutes there were twelve separate equipment malfunctions, including several common-mode failures, and operator errors… [The] steam-driven main and auxiliary feedwater systems tripped offline and could not be restarted from the control room…. the reactor coolant started to heat up. The reactor operators had their hands full as the primary system temperature rose four degrees per minute and pressure soon exceeded 2400 psi.

The Davis-Besse reactor was a near-twin of reactors at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant. If you, like me, grew up in the 1970s and 1980s you might have heard of Three Mile Island, as in 1979 it made some news. The next failure at Davis Besse exactly followed that script: “the pilot-operated relief valve cycled open and closed three times to relieve primary coolant pressure before it stuck open, just like at Three Mile Island.”

Two plant operators would have to improvise and run down several levels to the locked basement auxiliary feedwater rooms to reset the trip valves and start the pumps. Despite a “no running” policy, a pair of men bounded down the stairs. One operator was fleeter than the other, and the lagging operator threw him the key ring as he sprinted ahead. Once they removed the padlock, they had to descend a ladder, remove more chained locks, reset the pump’s trip valve, and reposition other valves.

The quotes are from the book Safe Enough? A History of Nuclear Power and Accident Risk, by Thomas Wellock. In his day job, Wellock is the official historian of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), an organization whose official responsibilities include screaming ‘Yes!’ to anyone who broaches this question. A coarsely cynical reader might thus expect Wellock to sidestep damning details of nuclear risk at the behest of his employer. This cynicism does a disservice to Wellock’s ambition.

Nuclear energy was quite popular in the early 1970s, with support in the US in the range of 70-80%. That changed after Three Mile Island, when support plummeted below 40%. But then, weirdly, in the 1990s support stabilized. Despite Davis-Besse, despite Chernobyl and Fukushima, in the US support for nuclear has stayed roughly in the bound of about 40-60% in the three decades since. Nuclear energy is perhaps unique as a technology, in that no amount of experience seems to change society’s comfort with it. The topic is forever radioactive.

Wellock sets out to tell this history, how the US public went from nuclear-lovers in the 1960s to suspicious in the early 1970s, hostile in the 80s, and ambivalent today.. Wellock does not try to hoodwink us with happy talk - he makes clear what the stakes are in nuclear energy, that in the case of Davis-Besse there was not simply a power plant at risk, but the potential to release radiation across America’s industrial heartland. Wellock tracks regulatory victories for the nuclear industry, and expensive defeats at the hands of activists, and, always, political posturing over its future.

Yet “Safe Enough?” is less of a history of events than a biography of an idea, the birth of “Probabilistic Risk Assessment” as the guiding principle for understanding and mitigating risks in complex systems. The heroes of Wellock’s book are not nuclear plant night shift assistant supervisors, or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission training and assessment specialists, though they each make important cameos. The city of Toledo, Ohio is not safeguarded by watchful superheroes. It is protected by a methodology.

There is a school of thought that sees nuclear risk assessment as a synonym for run-away civil service. Nuclear regulation is a monster that serves only itself, justifying increases in its budget by enforcing ever more draconian requirements, in defiance of reason.

Wellock’s history offers an instructive counterpoint. As becomes evident from story after story of nuclear ‘events’ like Davis-Besse, the sprawling bureaucracy of the NRC was the only rational response to the mathematics of risk itself.

The first fifteen years of operation of commercial nuclear power were relatively benign, at least in the sense that there were no major accidents. In Wellock’s telling, by the 1970s the essential dullness of nuclear energy was causing the industry a problem. If nuclear plants were to malfunction at some measurable rate, the industry could use that data to anticipate its next failure. But if the plants don’t fail, then it becomes very difficult to have a conversation about what the true failure rate is likely to be. Are the plants likely to fail once a decade? Once a century? Once a millennium? In the absence of shared data, scientists, industry, and the public were all free to believe what they wanted.

At its birth, the nuclear industry focused on imagining big risks, striving to prevent something called a Design Basis Accident. This was the kind of accident that made a manager feel important, protecting civilization from meltdowns with steel plates as thick as a bicep and concrete walls as wide as a Cadillac. Experienced engineers would concoct the worst event they could reasonably imagine, and if the nuclear design could contain it, well, it should be able to handle just about anything that life could throw at it.

By the early 1970s, after the civil rights movement and Vietnam and with Watergate in full swing, the public was becoming jaded with Big People waving away concerns with Big Promises on the basis of little more than self-proclaimed expertise. And thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, the public was close to accessing the details of what industry leaders actually knew. Big People recognized that this would not be an entirely good look.

So the Atomic Energy Commission did what industry and government always do in times of crisis: It formed a commission. It proposed to unveil to the public a better risk assessment tool, not so much for use by industry (since nuclear power was, to them, obviously safe), but as a particularly intense form of content marketing:

The AEC tried to reassure the public by answering what had been so far an unanswerable technical question: What is the probability of a major reactor accident? It was a tall order. How could engineers quantify the probability of an accident that had never happened in a technology as complex as nuclear power?

The leader of this effort to reinvent nuclear risk assessment was MIT engineering professor Norman Rasmussen, who was tasked with developing quantitative risk measures in terms easily understood by the public. Rasmussen recommended a radically sophisticated approach to risk assessment, leveraging a new technique called Probabilistic Risk Assessment.

The solution proposed by Rasmussen was to calculate the probabilities for chains of safety-component failures and other factors necessary to produce a disaster. The task was mind-boggling. A nuclear power plant’s approximately twenty thousand safety components have a Rube Goldberg quality. Like dominoes, numerous pumps, valves, and switches must operate in the required sequence to simply pump cooling water or shut down the plant. There were innumerable unlikely combinations of failures that could cause an accident… the potential for error was vast, as was the uncertainty that the final estimate could capture all important paths to failure.

In private, the fix was in, just as a cynic would expect. AEC Commissioner James Ramey was leery of an academic exercise he could not easily control, stating in 1973 “If it just shows one human life [lost], I’m against [publishing] it.” But despite the public relations risk of a negative result, the project went forward.

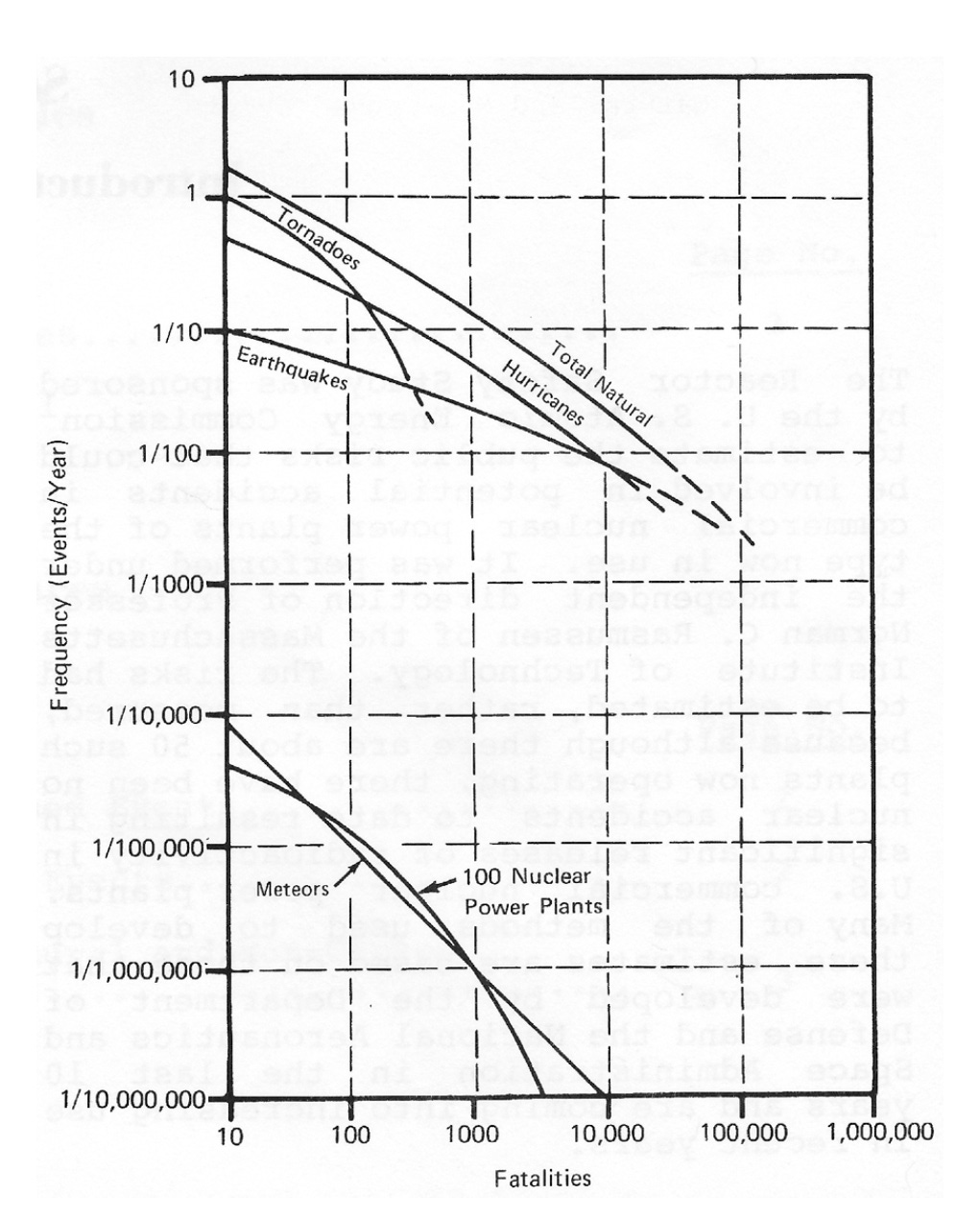

Rasmussen delivered. In January of 1974, after 60 person-years of effort, the Chair of the AEC reported to Congress that the odds of a significant meltdown were less than one in a million. Congress and the public could rest assured that nuclear energy was far safer than comparable electrical generation methods such as coal, or a hydroelectric dam. The risks were astonishingly small, akin to getting hit by a meteor falling from the sky. Commissioner Ramey had nothing to worry about. The academics showed that nuclear energy was plenty safe enough.

Probabilistic Risk Assessment grew to become the dominant language for analyzing nuclear risk, and launched a set of practices that changed the culture of the industry forever. Yet in 1974, nearly all of US nuclear generating capacity was less than 5 years old. Unsurprisingly, this first implementation of Probabilistic Risk Assessment was too simplistic.

The real world began to undermine Rasmussen’s rosiest, most headline-grabbing predictions almost immediately.

A plot from the Rasmussen Report estimating the likelihood of deaths from nuclear power as orders of magnitude less probable than dying from common natural disasters, closer to being killed by a meteor. There have been no known meteor deaths since this curve was published in 1974, though there is historical evidence that this is not impossible!

Let me put Wellock and Rasmussen aside for a moment, and try out a metaphor. The process of Probabilistic Risk Assessment is akin to asking a retailer to answer the question “What would happen if we let a flaming cat loose into your furniture store?”

If the retailer took the notion seriously, she might systematically examine each piece of furniture and engineer placement to minimize possible damage. She might search everyone entering the building for cats, and train the staff in emergency cat herding protocols. Perhaps every once in a while she would hold a drill, where a non-flaming cat was covered with ink and let loose in the store, so the furniture store staff could see what path it took, and how many minutes were required to fish it out from under the beds.

“This seems silly - I mean, what are the odds that someone would ignite a cat?”, you ask. Well, here is the story of the Brown’s Ferry Nuclear Plant fire, in March 1975, which occurred slightly more than a year after the Rasmussen Report was released, as later conveyed by the anti-nuclear group Friends of the Earth.

Just below the plant’s control room, two electricians were trying to seal air leaks in the cable spreading room, where the electrical cables that control the two reactors are separated and routed through different tunnels to the reactor buildings. They were using strips of spongy foam rubber to seal the leaks. They were also using candles to determine whether or not the leaks had been successfully plugged – by observing how the flame was affected by escaping air.

The electrical engineer put the candle too close to the foam rubber, and it burst into flame.

The fire, of course, began to spread out of control. Among the problems encountered during the thirty minutes between ignition and plant shutdown:

-

The engineers spent 15 minutes trying to put the fire out themselves, rather than sound the alarm per protocol;

-

When the engineers decided to call in the alarm, no one could remember the correct telephone number;

-

Electricians had covered the CO2 fire suppression triggers with metal plates, blocking access; and

-

Despite the fact that “control board indicating lights were randomly glowing brightly, dimming, and going out; numerous alarms occurring; and smoke coming from beneath panel 9-3, which is the control panel for the emergency core cooling system (ECCS)”, operators tried the equivalent of unplugging the control panel and rebooting it to see if that fixed things. For ten minutes.

This was exactly the sort of Rube Goldberg cascade predicted by Rasmussen’s team. Applied to nuclear power plants, the mathematics of Probabilistic Risk Assessment ultimately showed that ‘nuclear events’ were much more likely to occur than previously believed. But accidents also started small, and with proper planning there were ample opportunities to interrupt the cascade. The computer model of the MIT engineers seemed, in principle, to be an excellent fit to reality.

As a reminder, there are over 20,000 parts in a utility-scale plant. The path to nuclear safety was, to the early nuclear bureaucracy, quite simple: Analyze, inspect, and model the relationship of every single one of them.

“Safe Enough?” was not written as a defense of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s regimented style. But as an outsider reading about the math for the first time, it became clear to me that once the NRC chose to implement Probabilistic Risk Assessment, an intrusive bureaucracy became its destiny.

A cursory look at the math explains why. Our flaming cat needs only one path past our defenses for the fire to spread. Our flaming cat will test them all. This means that it does no good to be right, on average , about individual safety measures. Being overly optimistic about any single one of the paths to disaster is functionally equivalent to being wrong about all of them.

Asteroid deaths are rather easy to estimate - calculate the number of rocks falling from space, the density of people on the ground, and the average blast zone. Three parameters, done. It’s straightforward to explain.

The public is wary of nuclear risk, in part, because it is not at all like this. Neutrons don’t simply bounce around like billiard balls. A neutron colliding with an unstable nuclear generates more neutrons1. There are feedback loops. The public may struggle to articulate to an expert exactly what is bothering them (“I think you have failed to account for exponential growth mechanisms, and thereby truncated the uncertainty values in your estimates,” says Morgan Jacobs, nurse). But lay people are familiar with cats, and familiar with flames. The public possesses a rough intuition about Probabilistic Risk Assessment math that, while technically wanting, nonetheless captures its two critical aspects: (1) Small accidents will be much more likely than big accidents, but the big ones dominate the danger. And (2) the odds of an accident cascading out of control are probably higher than we expect.

I was eight when the Three Mile Island nuclear plant had its ‘loss of containment’ event. I was 15 when the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded. I understood these events in the same terms an adolescent understands anything: The adults are lying to us. To a teenager, there was no point in entertaining a defense of the industry. The entire enterprise dripped with poison.

Risk modelers did not get hung up on stories of heroes and villains. Risk modelers could see the specifics. To the engineers at the NRC, each component in the nuclear power plant was a singular object in their computer model, topologically linked to all the others through a set of gloriously tunable and testable parameters. The problem was not that society relied too much on the volatile and impenetrable math of Probabilistic Risk Assessment. It was that we did not take it seriously enough.

In a world where industry and activists fought to a standstill, Probabilistic Risk Assessment provided the only credible guiding light. Rasmussen and team first began to compile and model relevant data in the early 1970s. Over the decades the industry’s database grew, and the NRC developed an opinion on every valve, every pipe, the position of every flashing light in a plant. This angered the utilities, who could not move a button on a control panel without reams of test data and its associated paperwork. This angered activists when the refinement of models predicted safety margins could be relaxed.

But Probabilistic Risk Assessment has no emotions. Probabilistic Risk Assessment estimated, validated, learned. Probabilistic Risk Assessment would form the barrier protecting us from catastrophe.

Was this hubris?

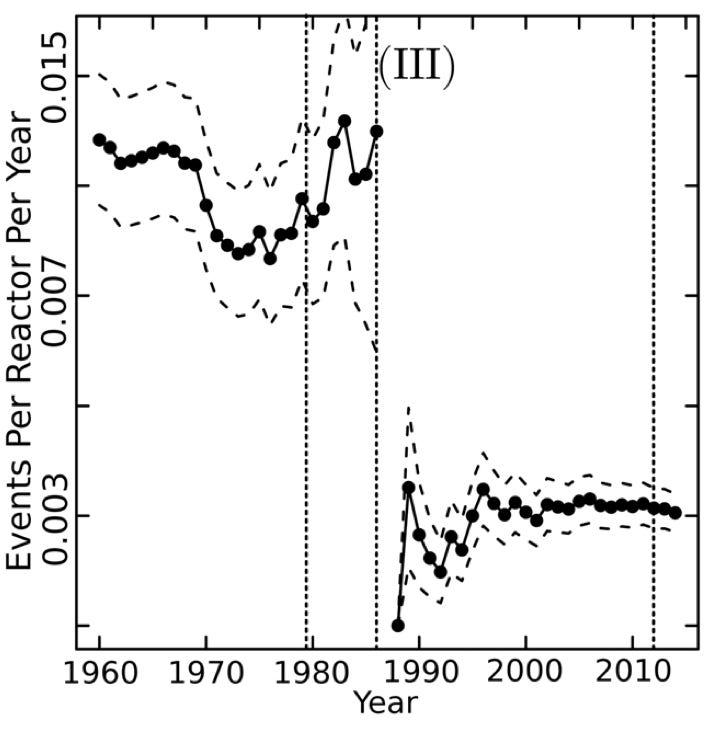

Wellock’s book is big on stories yet short on raw data. But a dive into the academic literature shows that, on implementing the teachings of Probabilistic Risk Assessment after Three Mile Island and (especially) Chernobyl, the rate of nuclear ‘events’ dropped by over a factor of 4.

A model of nuclear ‘events’, which are largely small failures that might require plant closure to replace equipment or redesign subsystems. Data points are dots connected by black lines, while the dashed lines above and below them represent uncertainty bars. The first vertical dotted line represents the failure of Three Mile Island in 1979. The second vertical dotted line represents Chernobyl in 1986; the third, Fukushima in 2011.

A combination of small failures could trigger a cascade to disaster. According to Probabilistic Risk Assessment, the rational approach is to sweat the small stuff. All of it.

Wellock’s book is at its strongest as an obsessively detailed chronicle of the transformation of nuclear plants into panopticons, with the NRC examining every detail of every part, systems diagram, user interface, and personnel training regimen. Risk was brainstormed, quantified, modeled.

Probabilistic Risk Assessment allowed regulators to break an unimaginable problem into parts that were easily visualized, communicated, and controlled. And in story after story, Wellock shows that it actually worked.

So did Probabilistic Risk Assessment deliver, and make nuclear power “Safe Enough?”

On March 16th, 2011, Japanese Prime Minister Kan Naoto learned that he would not have to evacuate Tokyo2.

This was five days after the Tōhoku earthquake, a slippage between tectonic plates so powerful that it moved Honshu, the main island of Japan, 2.4 meters to the east. The earthquake generated a tsunami 14 meters high, rolling over the coastline and submerging the protective sea walls of the Fukushima nuclear reactor. The water cut the plant’s electrical connection to the mainland and drowned its backup generators. Pumps responsible for passing 70 tons of water an hour to cool the reactors failed. Temperatures inside began to rise.

The next day, March 12th, the reactor Unit 1 melted down. Water began to react with the zirconium metal that made up the reactor walls, forming hydrogen. Pressure increased, pushing the hot gas through microscopic cracks in the vessel walls until it encountered oxygen outside. The resulting explosion spewed radioactive contamination throughout the building, and into the surrounding air.

On March 14th reactor Unit 3 exploded. On March 15th reactor Unit 4 exploded as well.

Unit 4 was the worry. It housed over 1500 spent fuel rods in open, water-filled pools at the top of the building, without any concrete structure surrounding it. With no active recirculating pumps, the water in these pools would heat and evaporate. When the pools dried out - or if the building collapsed, when it spilled out - the plant would become too radioactive to approach. Nuclear reactions would proceed uncontrolled. Radioactive cesium would release directly into the air, and be carried by winds into the surrounding population centers, possibly including Tokyo.

Before March 16th, the water levels in the pools were unknown.

In the worst case scenario, not made public until long after the disaster, the entire Tokyo Metropolitan Area - 35 million people - would have to be moved to temporary shelter. The very existence of the nation of Japan was at stake. And no one - not TEPCO, the utility that owned Fukushima, not the Prime Minister, not the Japanese military - could do anything but hope.

On March 16th, a military helicopter visually confirmed the rods were still submerged. Water, stored in the reactor above, had fortuitously cascaded downwards to refill the pool after Unit 4 exploded. The holding pool’s temperature was near boiling, but the fuel rods were safe. The unthinkable remained unthought.

Wellock is sympathetic to the notion that a full-throated embrace of Probabilistic Risk Assessment in Japan could have prevented Fukushima as well. The NRC had learned, from a second near-disaster at Toledo’s Davis-Besse plant in 20013, that corrosion in the culture of an organization could be just as dangerous as corrosion in materials. This was certainly true of TEPCO - the utility had considered, but rejected, higher walls to keep out the ocean from even a tsunami this large. The plant managers at the time opted to avoid publicly visible upgrades, ironically because they feared that new safety measures would relay the unwanted message that nuclear power was untrustworthy.

In hindsight it is clear that TEPCO performed poorly. It is less certain that it is realistic for nuclear operators and agencies to achieve perfect performance, in all countries, at all times. The Fukushima meltdown did not start with an accumulation of minor crises that Probabilistic Risk Assessment predicted would dominate failure. The Tōhoku earthquake was larger than was thought to be possible on the Honshu fault. Vulnerability to nuclear catastrophe might have sharpened through a slow accumulation of poor decisions. But the physical process was kicked off by a single, devastating event.

As a hero’s journey, Wellock’s history of Probabilistic Risk Assessment ends with disappointment. Our main character is forged in battle, its power spreads to dominate the kingdom, and then is… drowned by a Tsunami?

This is it? No triumph of nuclear safety? No happily ever after?

There is a temptation to record accidents like Fukushima as aberrations. The most important lesson of Probabilistic Risk Assessment, at least as applied to nuclear power, is that outliers like Fukushima are not simply one-off events that can be explained away as special circumstances. Outliers are, in many ways, the only events that matter.

This is where “Safe Enough?” is weakest. Wellock faithfully reports on what people said about math, but never allows the math to speak for itself. While engineering is the main character in this play, it exists like a Buddhist monk, in the perpetual present. It acts, or it is acted upon. It has no backstory, and it bodes no future.

To flesh out the character’s motivations, we have to place history aside, and focus like NRC’s engineers on the equations themselves.

Accidents that play out sequentially over time usually are best modeled as a cascade4. Left uncorrected, cascades grow exponentially in scale, one grain of rice falling down a pile to dislodge two, which fall further to dislodge four, then eight, then sixteen, until the entire pile collapses. If we were to run experiments on rice piles as our model of cascades, we’d find there is no ‘average’ collapse, a fact that is true both mathematically and metaphorically. Most events are small, insignificant. Then, without warning, a single occurrence dwarfs anything else experienced, with the number of fallen rice grains capped only by the size of the pile itself.

Earthquakes are cascades: The 1960 Valdivia earthquake off the coast of Chile was not simply big, it released a quarter of the combined energy of every earthquake ever recorded. Forest fires are cascades: The Camp Fire in California in 2018 destroyed as many structures as the next seven largest California fires combined.

Nuclear events are really two cascades in one. The first cascade is a loss of mechanical control, with damage largely limited to the physical plant itself. Left to continue, these failures trigger a second cascade, ‘loss of containment’, release of radiation to the broader world. Scientists have christened these sorts of linked cascades with the name ‘dragon kings’, befitting their immense power. Fukushima and Chernobyl were not simply the most extreme nuclear events on record, they were hundreds of times more costly than the next largest examples. It is not simply difficult to estimate the exact size of a particular nuclear event. It is difficult to estimate its order of magnitude.

We’d like to take comfort in the facts we have measured: Even considering Chernobyl and Fukushima, the economic and physical damages attributed to nuclear accidents have proven historically small. Nuclear advocates correctly point out that the solar and wind industry have caused more deaths than nuclear. (Exposure to radiation creates a probability of death; a tumble from sixteen stories creates certainty.) The total cost to clean Chernobyl and Fukushima may exceed a trillion dollars, but even consideration of this ‘tax’ would add only a penny or two per kWh to all the energy the industry has created in its history. The health and environmental damage from coal is easily ten times this.

Still. The advocates who intone solemnly on the importance of analyzing nuclear energy in terms of dispassionate numbers, as above, use the wrong models. To estimate the potential impact of cascades, we cannot simply average what has been. Our models have to consider the total damage possible - the number of rice grains in our pile, the energy of the atoms in our nuclear fuel.

In 2011 Japan experienced an immense amount of bad luck, punctuated by a single bit of good: Fukushima Reactor 4’s exposed fuel rods stayed immersed. The avalanche of disaster stopped. Tokyo was spared.

Is it right to ignore the cost of the evacuation of Tokyo, merely because an unplanned flow of water saved us? What if we assume the maximum cost of a nuclear event is not $1 trillion for the Fukushima we lived, but $10 trillion for the Fukushima we escaped5? [5] Is nuclear still safe enough then? Five decades of development Probabilistic Risk Assessment has answered innumerable small questions about nuclear energy, but has failed to address the one question we care most about.

In the end, “Safe enough?” is simply not a proper question to ask of a cascade. There is no conspiracy of industry or activists manipulating the public and hiding the truth. If Wellock’s readers leave the book unsatisfied, that is not entirely the fault of the writer. It’s the nature of the math.

To take Probabilistic Risk Assessment seriously requires that we think beyond intuition and experience, and place our faith in an intricate web of calculations and simulations. That we celebrate meticulousness over freedom and invention. That we recognize that while our vigilance will protect us from some catastrophes, it will never shield us entirely.

In 2019 three executives of TEPCO - their chairman and the two leads of their nuclear division - were found not responsible in criminal court for the Fukushima disaster that occurred under their watch. In a victory for the nuclear industry, the presiding judge, Kenichi Nagafuchi, wrote without irony, “It would be impossible to operate a nuclear plant if operators are obliged to predict every possibility about a tsunami and take necessary measures.”

Despite all the benefits of Probabilistic Risk Assessment, the judge’s words were not wrong. “Safe enough” remains forever the illusion we live with, until the moment we don’t.

-

Fun fact: There are about 40,000 generations of neutrons every second. This is something the public is dimly aware of because, well, weapons. The known speed of these feedback loops is probably a source some of the public’s hesitation around nuclear energy - one of the public’s Bayesian priors, if you like to frame it in terms of logic. But it’s not a topic I’m going to dig into here.

-

For this summary I want to cite three sources that I found particularly useful. First, Fukushima in review: A complex disaster, a disastrous response, published in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Second, The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and the DPJ: Leadership, Structures, and Information Challenges During the Crisis published in Japanese Political Economy. Third, The official report of The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission. Wikipedia’s summary is of course excellent as well, but these more academic sources provide an excellent source of stories, and further understanding for the social and political context in Japan at the time of the event.

-

There was another near-accident at Davis-Besse in 1977, recounted by the shift supervisor here. The story is another absolutely textbook example of how Probabilistic Risk Assessment would have diagnosed a problem that earlier methods missed. Had this incident been taken seriously, disaster at Three Mile Island would have been averted.

-

Scientists will get into knock-down drag out fights over whether a given data set fits a mathematical form called a ‘power law’, or match better to a ‘log normal distribution’, where outliers are large but not as dominant. As a point of reference, events that build up one event after the next are commonly power laws, but physics can be subtle, and it turns out an avalanche of snow isn’t a great fit to a power law, while one of rice grains is. As a practical matter, we should focus on the degree to which the worst case event outstrips the rest of the distribution. Generally speaking Nuclear meltdowns should be expected to (and do) mathematically best fit to dragon kings; once an event exceeds a certain damage threshold, it undergoes a “phase change” to a new and much more significant damage mechanism. In the case of nuclear power, the potential maximum cost shifts from “things capped by the budget of a nuclear plant” to “things capped by the budget of a regional economy”.

-

In 2007, the Institute for Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety (IRSN) assessed disaster scenarios at the Dampierre power plant in Loiret, near Paris. The worst case assessment came out at $5.8 trillion, triple the GDP of France itself. The Tokyo metro area has a GDP roughly twice the Paris metro area, so a $10 trillion estimate is not nuts, though truthfully the people of Japan might simply decide to just live with the fallout rather than pay that figure.