Your Book Review: Secret Government

[This is one of the finalists in the 2023 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

There is widespread agreement among philosophers, political commentators, and the general public that transparency in government is an unalloyed good. Louis Brandeis famously articulates the common wisdom: “Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman” (page 1).

Support for transparency is bipartisan. On his first day in office, Barack Obama said “My administration is committed to creating an unprecedented level of openness in Government.” (page 1). On the Republican National Committee’s website, one reads “Republicans believe that transparency is essential for good governance. Elected officials should be held accountable for their actions in Washington, D.C.” (page 2)

And so it is. Legislators’ votes are published and stored in public online databases, their deliberations are televised, and their every action is extensively documented.

We do not, however, embrace transparency in all aspects of government. Citizens vote by secret ballot to protect their votes from outside influence. The Federal Reserve meets in secret to avoid causing turmoil in financial markets. Most international diplomacy is conducted in secret. What accounts for the difference?

As with a surprising number of widespread assumptions, the public embrace of transparency suffers from a want of theoretical justification. The intuitive thought process begins with the assumption that politicians are inherently up to no good. They must therefore be watched as closely as possible so that we can temper their sordid tendencies. A more careful examination of transparency paints a much more complex story. Brian Kogelmann provides such an examination.

How Did We Get Here?

Our modern ideas about government transparency can be traced back to Jeremy Bentham. He advocated for radical transparency in government while also supporting a secret ballot for individuals. He believed that “men acting as representatives of all the people have a private and sinister interest, and sufficient power to gratify that interest, producing a constant sacrifice of the interest of the people” (page 23). What should be done about this? Publicity! For “Without publicity, all other checks are fruitless: in comparison of publicity, all other checks are of small account.” (page 24).

Bentham also shares our modern embrace of a secret ballot for citizens. On its face, there might seem to be a contradiction here. If citizens’ votes were public, would that not also serve as a check against their being captured by sinister self interest? Some have bitten this bullet. John Stewart Mill, for example, thought that citizens should vote publicly so that they would be compelled to vote in the public interest rather than their own. Voting publicly might also increase trust in government by allowing us to easily check the results of any election. If there was a public database of votes, citizens could simply check whether their votes were counted accurately. Any concerns about election fraud would evaporate.

Bentham resolves the apparent contradiction by appealing to the idea that the votes of citizens should be free. By this he means free from outside influence “whether as terrorism or bribery” (page 24). The idea is that if citizens’ votes were public, they would be subject to a variety of unsavory influences. Somebody might try to buy their vote, for instance. This was commonplace in the United States before the secret ballot was introduced. Also common was “terrorism,” simply threatening physical violence against anybody that didn’t vote in the appropriate manner. Organized crime was a fan of this tactic. The secret ballot removes these influences, ensuring that the only factor affecting an individual’s vote is the honest preference of that individual.

By contrast, Bentham absolutely does not want the votes of legislators to be free. He wants their votes to be tightly shackled to the preferences of their constituents. He wants the citizenry to essentially rule by terrorism, threatening to put legislators out of a job if they step out of line. This can only occur if those constituents can actually observe their legislators’ votes. So there is, apparently, no contradiction.

A Secret Ballot For Legislators

Kogelmann does not think that the contradiction has been resolved. He argues that legislators face an incentive structure very similar to the one faced by citizens, and that a similar system should be adopted. In his words:

…our political institutions ought to largely operate under a veil of secrecy. By secrecy, I mean this: when representatives vote on bills (either on the legislature floor or in committee), they do so by the secret ballot. Citizens will know which bills pass or fail, and they will know the total number of votes for and against each bill, but they will not know in which direction individual legislators cast their votes. Moreover, much of the debate over bills (especially in committee during markup sessions) should occur behind closed doors. (page 35)

His argument relies on the notion of political equality, which he defines thusly:

A democratic society realizes political equality if and only if influence on political decisions is insulated from features of persons other than (p1) their desire to participate in politics, (p2) the quality of their argument, (p3) their relevant expertise, or (p4) their unique position to advocate a particular cause (page 39)

Kogelman claims that a certain amount of opacity in government is necessary to realize political equality.

A full discussion of the topic of political equality would take us somewhat far afield, so no extensive justification for this particular conception is given here. I will appeal to the intuitive plausibility of the idea that we should begin with the presumption that all citizens should have equal influence on political decisions. But we also recognize that there are some situations where some individuals should have more influence than others. Some individuals have no interest in politics, and no wrong is done to them if they have less influence than individuals that are very interested in politics. Some are highly articulate and can shape political discourse around their ideas. It would be undesirable and probably impossible to try to deny outsized influence to thought leaders. Some individuals have technical expertise in a particular area such as nuclear power or human behavior. They ought to have more influence than the lay public on those issues.

Conversely, many intuitive things are not legitimate exceptions. Some individuals have more money than others. Some work odd hours and are more inconvenienced by getting to the polls on election day. Some run crime syndicates and can threaten anybody that approaches the polls. We do not think that these qualities entitle those individuals to greater political influence.

Important for the current discussion, political equality does not seem to be realized in many modern democracies (despite very high levels of transparency). The classic example of this is the 2014 paper by Gilens and Page, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” in which the authors demonstrate that legislators in the United States are highly responsive to the preferences of interest groups and economic elites, but essentially unresponsive to the preferences of average citizens.

In graph form:

Kogelmann also cites others, including “Gilens 2005, 2012; Flavin 2012; Rigby and Wright 2013; … Bartels 2016” (page 40), and concludes “it certainly seems like wealth is leading to unequal influence on political outcomes” (page 40). I agree. There is enough smoke here to indicate some fire.

Having large amounts of wealth and being a member of a special interest group are not among the enumerated exceptions to the presumption of equal influence, so we can say that political equality is not realized.

Assuming for the moment that interest groups can and do influence legislators, how, precisely, does that happen? Not in the way that many initially think. The empirical literature is somewhat mixed on the question of the influence of money in politics, mostly because of the conflation of several different measures of influence.

Very briefly, a bill begins its life in a committee, stays there for a while getting debated over and reworked and amended until the committee brings it to the floor where all members of one legislative house vote on it. If passed, the bill is sent to the other house and the rigamarole begins again. Those studies that find no effect of money on legislator behavior tend to focus on floor votes.

After conducting a meta-analysis of all relevant studies, one group of scholars concludes “the evidence that campaign contributions lead to a substantial influence on votes is rather thin” (Ansolabehere et al. 2003:116). Other scholars find different results, however. From his meta-analysis, Thomas Stratmann (2005:146) concludes that “money does indeed influence votes.” (page 43)

The studies that find a large influence of money on legislative outcomes focus on the efforts of legislators during the drafting phase, in committee.

Instead of purchasing votes, these subtler accounts posit, what is being purchased is such things as making sure that a bill one supports is prioritized, making sure that a bill one opposes never reaches the floor for a vote, inserting an amendment or earmark, and making sure that a bill one opposes but will inevitably be passed a bit more palatable. (page 44)

This account is widely confirmed in the literature. Kogelmann cites Hall and Wayman (1990) among others

In short, the more money a supporter received from the dairy PACs and the stronger the member’s support, the more likely he or she was to allocate time and effort on the industry’s behalf (for example, work behind the scenes, speak on the group’s behalf, attach amendments to the committee vehicle, as well as show up and vote at committee markups) (page 44)

The idea of lobbying as a straightforward exchange of money for legislative action relies on the lobbyist having some confidence that the legislative action will actually be delivered. If the legislator would routinely take the money and run, exchange would soon cease to take place. There is no outside authority enforcing the contract, so an informal mechanism must be at play. The commitments of the two parties need to be credible.

From the lens of game theory, the problem of credible commitment is solved in practice because the interaction between legislator and lobbyist is repeated many times. The legislator establishes a reputation for delivering legislative actions, and the lobbyist establishes a reputation for delivering money.

Give me a contribution today, and I will return the favor during my next term in office, provided that I win office and an opportunity to do you a favor arises. Moreover, if you support me in future campaigns as well, then you may become my friend, and if this occurs and I continue in office or achieve a higher office, then I will return even greater favors (Snyder 1992:17-18). (page 51)

If legislators voted by secret ballot, this resolution mechanism would cease to function. Say that a lobbyist makes a contribution to a legislator hoping for an amendment to be inserted into a bill. The legislator can promise up and down to vote in favor of that amendment, but will have no way to actually prove it. With no way to verify that the exchange took place, the lobbyist would soon give up.

In Kogelmann’s words:

In a regime of secrecy, interest groups cannot observe legislators expending effort on their behalf. They can thus never be sure the legislator has carried out her end of the bargain. Knowing this, the interest group is unlikely to enter a bargain in the first place. Opacity thus eliminates one source of political inequality, as it renders a legislator unable to credibly commit to fulfilling her side of an exchange. (page 54)

Lobbyists and legislators are currently able to cooperate with each other because the public nature of the legislator’s actions produces confidence in the lobbyist. The ideal of political equality would be served by using secrecy to disrupt this relationship. Removing the public record levels the playing field.

Bentham was correct, in a sense. The votes of legislators are not free. They are subject to a form of bribery, and also to terrorism.

Kogelmann does not address this angle in his book, but there is good reason to believe that terrorism is an even more effective tactic than bribery. Instead of making a contribution to a legislator to try to get an amendment added, the lobbyist can instead threaten to donate to a primary challenger or run a bunch of attack ads.

The following citations are taken from https://www.congressionalresearch.org/BruberyCitations.html

From the book Captured by former senator Sheldon Whitehouse:

The threat is plain: step out of line, and here come the attack ads and the primary challengers – all funded by the deep pockets of the fossil fuel industry.

From “The Negative Agenda Power of Campaign Contributions: Evidence from U.S. Congress” by Alberto Parmigiani:

Observable donations are just a limited fraction of the ones that interest groups threaten to make, so that the influence of donors to legislators is much bigger than the observed amount of contributions.

This dynamic would also cease to function by increasing the opacity of Congress. There would simply be no way to know who to attack.

Kogelmann also cites the problem of asymmetric information. The problem is essentially that interest groups tend to form around issues that have concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. This incentivizes a small, well-organized minority to spend a lot of time and energy monitoring Congress, usually pushing policies that do not benefit the majority.

For example, the benefits-to-costs ratio for corn growers forming an interest group and securing corn subsidies is high (the result is a substantial increase in wealth for the farmers). In comparison, the benefits-to-costs ratio for taxpayers forming an interest group and blocking corn subsidies is low (the average taxpayer only contributes a dollar or two to corn subsidies a year). This is why we see interest groups lobbying for corn farmers but none lobbying for taxpayers opposed to corn subsidies (page 45)

The idea of citizens caring a lot about their legislators’ actions on an issue that may cost them a dollar or two per year is fanciful, so there will be no opposing interest group to the corn growers. The returns on organizing are just not there.

The NRA operates on a similar dynamic. It spends a good deal of its time and money on the task of making sure its members are informed about one particular issue, resulting in policies that are objectively unpopular among Americans.

Being on the good end of a policy that has concentrated benefits and diffuse costs is not one of the enumerated exceptions to the ideal of equal influence, so this constitutes a violation of political equality.

There are two intuitive ways to solve the asymmetric information problem: “leveling up” the knowledge of the general public or “leveling down” the knowledge of interest groups. The former seems more morally righteous, but is unlikely to work in practice. The information about legislators’ votes is already public and easy to access (see govtrack.us). It is unclear how exactly one would make citizens care enough to organize. Legislators vote thousands of times per year, and some kind of government service attempting to push knowledge of all those votes onto the public would quickly be regarded as spam.

More practical is leveling down the interest groups by having an opaque legislative process, making all interest groups equally uninformed.

…legislators will no longer have an incentive to pass the corn-subsidy bill that a majority of people oppose. Of course, they still might pass the bill; perhaps they think that the production of corn needs and deserves financial support. The point is that if they do decide to pass the policy, it will not be because special interests are breathing down their necks. The introduction of secrecy has eliminated this incentive. (page 57)

If all groups are equally uninformed, loud, well-informed, well-organized special interest groups would no longer have an outsized influence on the political process. It would not be clear which legislators were and were not cooperating, so there would be no information for the members of the interest group to act on. This would increase political equality.

Drawbacks of Secrecy

Secrecy has some tempting benefits. Does it also have costs?

Maybe. We would like legislators to be accountable to the citizenry in some sense, but whether transparency provides a desirable kind of accountability is not clear.

Legislators are currently accountable in the sense that they might be voted out of office if their constituents are unhappy with their performance. The citizens rule by a kind of terrorism. What does this mean in practice? Jane Mansbridge gives three formulations, which Kogelmann enumerates.

First, promissory representation :

According to this account, politicians make promises to their constituents during elections and then seek to fulfill these promises once in office. Promises made by politicians might be to support certain kinds of legislation (e.g., subsidies for corn farmers or funding for local schools) but might also be to not support certain kinds of legislation (e.g. “Read my lips, no new taxes”). (page 59)

This account has a certain intuitive appeal, and, unfortunately, is incompatible with secrecy.

Account number two is anticipatory representation :

Instead of making electoral promises and then trying to fulfill them, here the politician tries to please future voters by passing policies that increase their well-being. (page 59)

Here, citizens do not look at their representatives’ actions, but only inspect their own well-being and vote accordingly. They do not need to know anything about the details of what laws have passed, or even if any laws have passed. If things suck, throw the bums out and try again. Given that the overwhelming majority of citizens do not monitor their representatives at all, this account seems more realistic, though potentially a little unfair to the legislators. Citizens’ well-being might decrease for some reason that has nothing to do with any legislative action. Anticipatory representation is, however, fully consistent with opacity.

Third is gyroscopic representation :

The idea here is that citizens elect a politician who is of a certain type; perhaps the politician is an evangelical Christian or a member of the steelworkers’ union. Because the representative they have selected is of a certain type, the electorate need not worry too much about what the representative does in office, as they already know what kinds of policies the elected official is likely to support. (Page 60)

This is also consistent with opacity because the observation takes place before the representative takes office.

Secrecy in government is only a problem, then, if we are fully committed to promissory representation. Kogelmann argues that we should reject the intuitive appeal of promissory representation because it will inevitably lead to pandering: politicians supporting policies they know to be bad or ineffective because of popular support. For an enumeration of all the ways in which expert opinion differs from lay opinion, see Bryan Caplan’s book The Myth of the Rational Voter. I would go further and argue that the reason citizens elect representatives in the first place is because of this difference of opinion. Citizens do not want to spend all of their time embroiled in the arcane details of healthcare regulation or fiscal policy. They want somebody else to do the work for them. The fact that opacity conflicts with promissory representation, then, is not a problem.

Shut the Doors

Should legislators also deliberate in secret? Kogelmann argues yes on this front too.

The US Senate is often hailed as the “world’s greatest deliberative body,” but those who have recently paid close attention to debate on the Senate floor are likely to find this description deeply inaccurate if not an exercise in sarcasm. Productive debate is almost nonexistent. Absent are honest exchange and consideration of reasons; in their place we find partisan displays of grandstanding. There is little compromise, and consensus is almost never reached. Of course, deliberation on the Senate floor need not manifest itself in such an unpleasant form. Institutions can have a major impact on the quality of discourse, and one institutional change that can influence the quality of deliberation is whether debate is open to the public or occurs in secret. (page 64)

The United States actually began with secret deliberation. The Constitutional Convention was held entirely in secret. The public was not allowed to observe, the doors and windows were sealed, and the minutes were not published until the death of James Madison in 1840. Deliberating in this manner had a number of desirable effects.

Designing a political system is very hard to do. The process of solving any hard problem involves confusion, mistakes, false starts, and the generation of a wide variety of ideas, many of which are bad. All of this is more difficult, if not impossible, when the process is publicized. Think of the last meeting you had where a hard problem was to be solved. Imagine how differently you would have behaved if that meeting was broadcast on national television. If a colleague used a word that you didn’t know, would you have asked what it meant? Would you ask a colleague to explain a confusing proposal a second time? Would you throw out a bunch of unconventional ideas? Would you give due consideration to unconventional ideas that others proposed? Would you be comfortable changing your mind? What if the audience could also choose to put you out of a job in a year or two if you made a sufficiently embarrassing gaffe or didn’t put forward enough partisan red meat?

Removing the audience allows participants to make mistakes more freely and eliminates the incentive to pontificate and grandstand instead of discussing substantive issues.

As former senator Olympia Snowe (R-ME) describes it, “Rather than putting forward a plausible, realistic solution to a problem, members on both sides offer legislation that is designed to make a political statement. Specifically, the bill or amendment is drafted to make the opposing side look bad on an issue and it is not intended to ever actually pass” (page 67)

It’s not that legislators don’t want to compromise. It’s that they don’t want to be seen compromising.

Are there any drawbacks? A few, but they are not insurmountable.

Kogelmann lists four. First, the legitimacy gap:

Contemporary liberal societies are rife with stark disagreements among good-willed and competent persons. Despite this lack of agreement, political decisions still need to be made, and typically there is no policy that will appease all persons affected. Someone is going to be the loser. Many times, this loser will feel that her views were not given due consideration; in turn she will begin to question the legitimacy of the implemented policy and the wider political process. (page 69)

Observing the process has the potential to mollify the loser and eliminate the legitimacy gap. If the losers observe that their opinion was at least considered during debate, they are plausibly less likely to view the process as illegitimate, even if their views are ultimately rejected. Note, however, that this requires citizens to actually observe their legislature.

Second, the problem of political capture:

The problem of political capture occurs when public officials use the apparatus of the state to advance their own self-interest rather than the public good.

This problem has constituted much of the rationale for transparency. Politicians have the power to make laws, and they might make laws that benefit themselves at the expense of the public good. Transparency compels them to at least be a little creative in their rhetoric. Instead of saying outright “We should award this contract to my cousin Ted,” they must make up some rationale for why Ted’s company deserves the contract.

A famous example of this problem is from the Constitutional Convention. Slave states didn’t try to offer any kind of justification for slavery. Instead, they simply stated that they would refuse to join the union unless slavery was allowed. This would have been harder to do if the meeting was held in public.

Third, the respect deficit:

The respect deficit occurs when individuals do not think those they disagree with are good-willed and competent, nor do they think their positions are in any way defensible. Though deliberation itself cannot resolve our deepest disagreements, it can perhaps reduce or eliminate the respect deficit. When we actually hear the reasons and arguments persons give in defense of views we think are misguided, we are more likely to walk away with a positive view of those we disagree with and the views they hold. (page 71)

I think the key word in this passage is “perhaps.” Observing political discourse in the United States, transparency doesn’t seem to be having a large effect on the level of respect people have for those with differing views. Perhaps it is necessary but not sufficient.

Fourth, the problem of ignorance :

Questions related to politics are complex and multifaceted. No individual knows everything there is to know about the intricacies of health care policy, business cycles, budget deficits, and the like, but democratic politics calls on individuals to play some participatory role in governance nonetheless. (page 71)

It is in theory desirable for citizens, particularly students of public policy, to have some information about the problems that have been previously solved and the issues that were brought up so that the collective level of knowledge can be raised. A transparent legislative process could plausibly help with this. We should want to shield future generations from our mistakes, which would seem to require that those mistakes be made public.

One potential solution to these problems would be to publish transcripts of legislative sessions after a period of time. Kogelmann calls this transcript accountability. This would solve the four above problems to the degree that open deliberation does. Unfortunately, this would come at the cost of removing all the benefits of secret deliberation. We actually have a natural experiment to demonstrate this. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has always deliberated in secret, but in 1993 started to release transcripts of their meetings on a 5-year delay. This change was examined in several papers by Ellen E. Meade and David Stasavage. They say:

Distinguishing between FOMC members who are Board Governors, those who are voting Presidents of regional Federal Reserve Banks, and those who are non-voting Presidents, we find that the two former groups have been significantly less likely to express verbal dissents on policy decisions since 1993 (page 83)

And “the 1993 change appears to have resulted in a reduced tendency for members to publicly change their views during the course of a meeting” (page 83).

This is essentially what secret deliberation is trying to avoid, so transcript accountability is out.

Better is what Kogelmann calls testimonial accountability:

The public exhibits Testimonial Accountability with respect to a secret deliberative body if and only if members of the body release statements to the public explaining, justifying, and criticizing the body’s decision. (page 77)

The canonical example of this is the Federalist Papers, following the Constitutional Convention. Several members of the convention published essays that aimed to promote the ratification of the Constitution. They also provided insight into the founders’ intent, offering detailed arguments in favor of a strong central government and a balanced division of powers. This helped two of the four problems: the respect deficit and the problem of ignorance.

If the respect deficit is reduced by open deliberation, it is probably reduced more by testimonial accountability. Reading a polished, cleaned up argument for a position is probably better than listening to a fumbled, half-baked speech given in a meeting. It is easier to respect the articulate, and most people are relatively inarticulate when speaking off the cuff.

The problem of ignorance is also likely to be reduced. Anything that an audience can learn by watching a legislative session they can probably learn more efficiently by reading a polished summary of that session. I expect most people who actually take advantage of this information to be students, researchers, and historians.

Testimonial accountability does not have any of the drawbacks of transcript accountability. There would be no reason to include the specific missteps and gaffes of any particular participant, and no way to check the veracity of such statements anyway. The problems with transcript accountability occur when the minute details of a debate are published, not the general direction and conclusions.

The other two problems are a bit tricker. Notably, Kogelmann doesn’t think that testimonial accountability reduces the legitimacy gap because members could just lie and say that they considered a point of view that they completely ignored. I think that testimonial accountability would do something to address this problem, but I agree that it is not a complete solution.

The complete solution he proposes is proportional representation. Unlike winner-takes-all systems, political parties in proportional systems secure seats in a legislative body in proportion to the number of votes they receive. It allows for a more diverse representation, reflecting the preferences of a broader electorate. Proportional representation systems aim to create fairer outcomes, reduce wasted votes, and foster collaboration and consensus-building in government. Whether this actually works is a matter of some debate.

In theory, proportional representation should reduce the legitimacy gap. If any viewpoint large enough to constitute a minor political party is given at least one seat at the table, we have good reason to believe that that viewpoint will be considered in debate.

It is also plausible that proportional representation will reduce the problem of political capture.

In Kogelmann’s words

In the context of secret deliberation, the worry is not that political actors hidden from the public’s eye will pursue their own interests, but that deliberators will advance their interests at the expense of those not present. This seems to be what happened at the Philadelphia Convention. Slaves, women, and the unpropertied were not present, so the interests of white male property holders could be advocated at their expense. (page 86)

Fundamentally, the resolution of political capture lies in the fact that people with many different interests have to compromise and agree on a solution that is palatable to all. Even if every member of a deliberative body is trying to pursue their own interests, as long as a sufficient breadth of interests is present, everything should cancel out.

The combination of testimonial accountability and proportional representation should address all the problems with secret deliberation.

Final Thoughts

The United States actually had a system that had most of the elements that Kogelmann proposes for most of its history. The changeover happened in the early 1970s with the introduction of the sunshine reforms. Legislators’ votes in committee used to be secret (though floor votes were public) and committee meetings were completely closed to the public. Did anything interesting happen after the switch?

As a matter of fact, yes!

Here is a selection of graphs from https://applieddivinitystudies.com/1970/ and

https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/

You have probably seen this one:

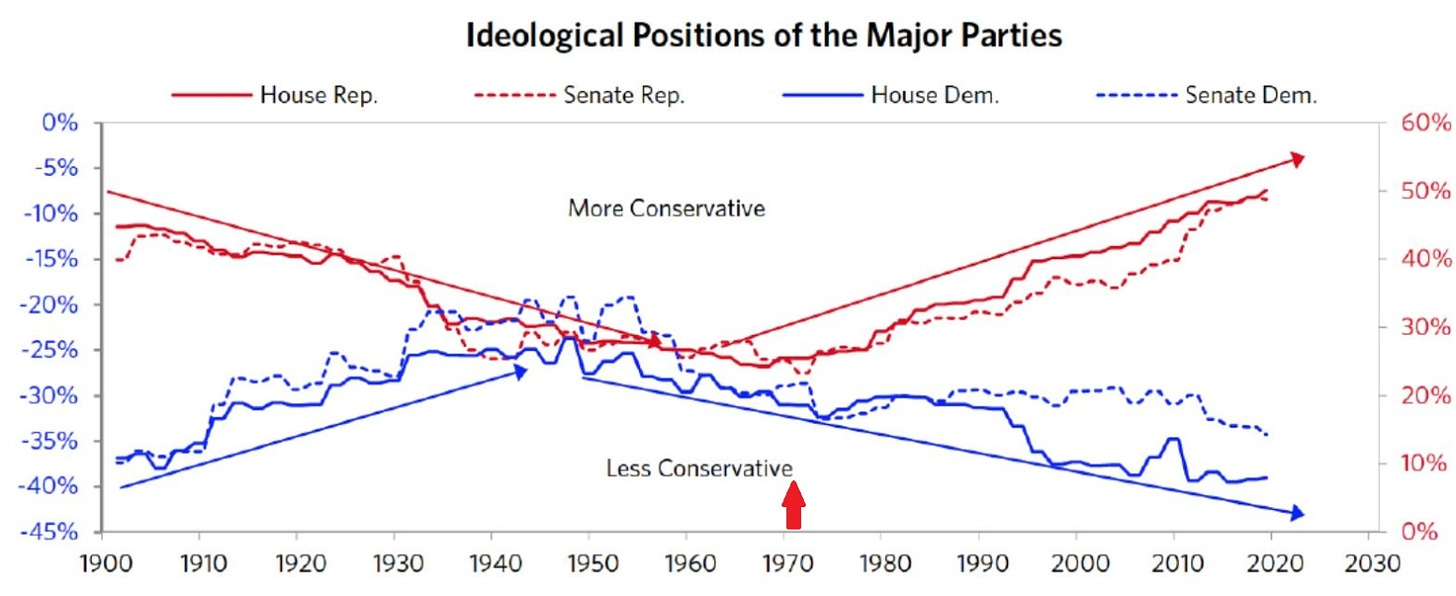

Our current trend of increased political polarization seemed to begin around that time:

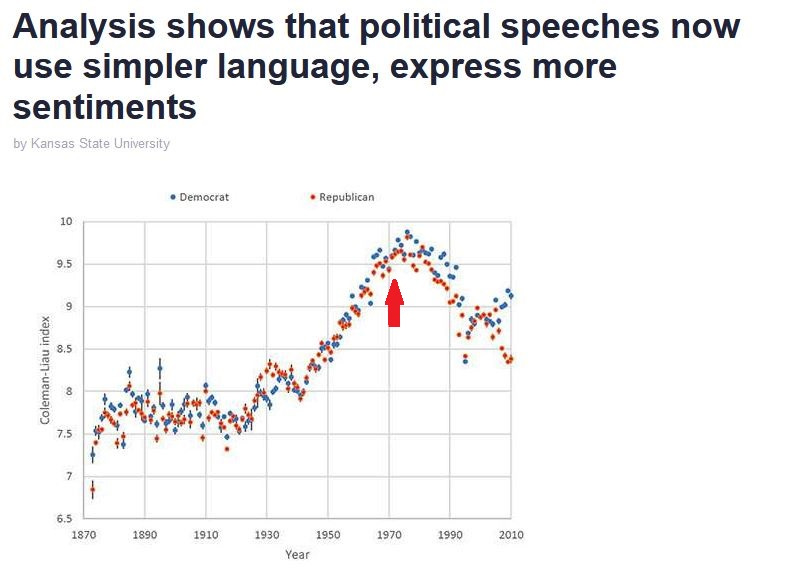

Along with a change in political rhetoric:

Mass incarceration arguably began in the early 1970s:

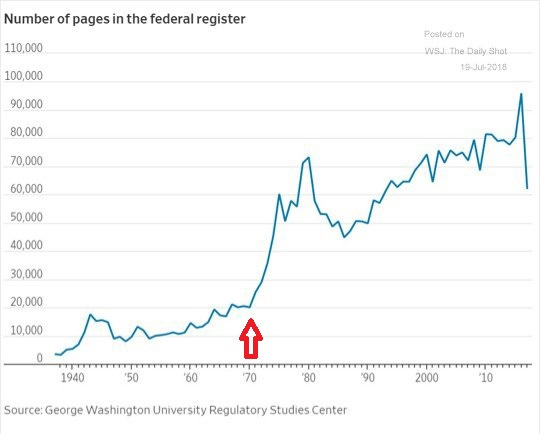

The federal register contains, among other things, a list of new laws and regulations. Its length began to balloon in 1970:

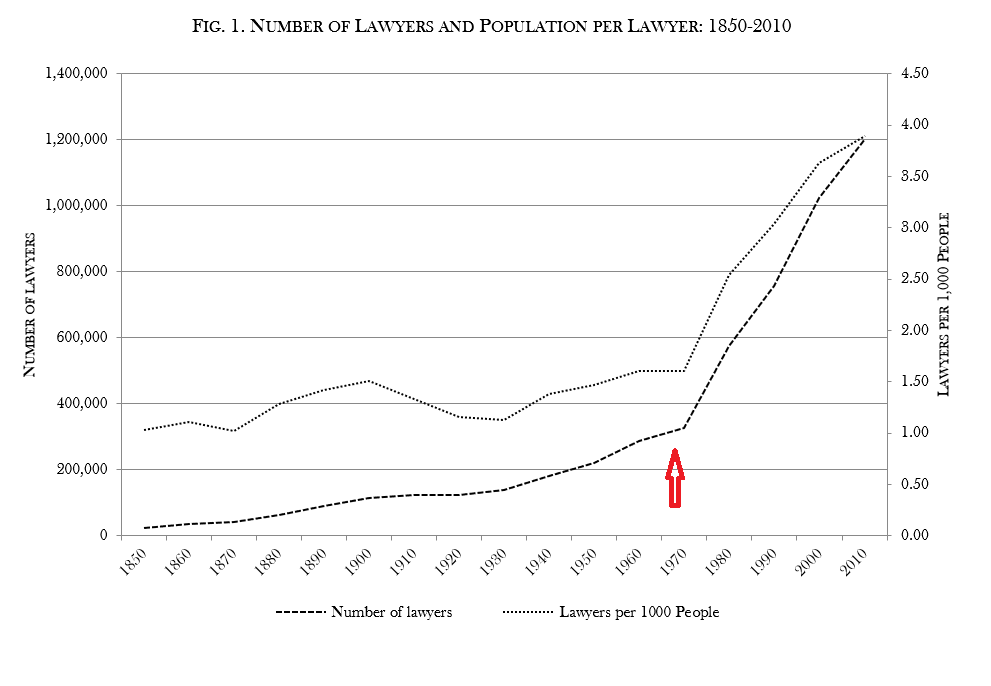

And most troubling of all:

I assert that the United States should go back to the old system. The theoretical justifications for transparency are weak, often empirically false, and the costs are high.

In order for citizens to hold legislators accountable for their actions, citizens must follow congress, which they do not do. Transparency is supposed to increase trust in government, but according to this study by Pew https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2015/11/23/1-trust-in-government-1958-2015/, trust in government did not increase and arguably decreased after the 1970s transparency reforms. Transparency is supposed to increase legislative accountability, and it does, but in the worst possible way. We would be better off with much less of it.

Postscript

I have only touched on the first three chapters of Kogelmann’s book. The rest is also interesting and worthwhile, but somewhat distracts from the agenda that I’m trying to push with this post.