Your Book Review: The Accidental Superpower

[This is the eleventh of many finalists in the book review contest. It’s not by me - it’s by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done, to prevent their identity from influencing your decisions. I’ll be posting about two of these a week for several months. When you’ve read all of them, I’ll ask you to vote for your favorite, so remember which ones you liked. If you like reading these reviews, check outpoint 3 here for a way you can help move the contest forward by reading lots more of them - SA]

In The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder _(2014), Peter Zeihan predicts the future of world politics and economic development in a way that an ACX fan would appreciate. He puts a timeline on it. The book isn’t about “some hazy distant future after we’re all dead and gone, but the future we will all be living in for the next fifteen years of our lives.” Zeihan’s subtitle hints at his big and bold thesis, which predicts “the dissolution of the free trade order, the global demographic inversion, the collapse of Europe and China,” which “is all just a fleeting _transition ” to a world largely abandoned by America.

People have fun making predictions like this (and mocking those who get things spectacularly wrong). With money and fame available to people whose predictions turn out right, and the ease with which we forget bad predictions, we should expect many such visionaries. However, regardless of whether you agree with Zeihan’s particular vision, The Accidental Superpower presents a set of analytical tools that should be useful for anyone interested in little questions like which countries will obtain power and wealth in the future, and which will collapse in war and poverty. (In case you didn’t catch it from the title, Zeihan says that America is going to be the biggest winner in the world to come.)

1: A model for power and wealth creation: geography, technology, and demographics

Zeihan’s primary models are influenced by his geographic-based perspective on how our world works. As he puts it in the introduction, “Geopolitics is the study of how place [rivers, mountains, etc.] impacts… everything.” 1 Early chapters discuss what he calls the balance of transport , which is roughly easy transport within a country (for economic development and forming political and cultural ties) and hard transport from outside of it (for defense). These transport issues are inherently tied to geography. What’s the best way to move things? Water-based transportation is extremely cheap. Think 17 cents per container mile vs. $2.40 for semis on an American highway, with a more extreme disparity for other countries, trade between continents, and populations in hard-to-access places. On the defensive side of that equation, geographic features on borders such as deserts, mountains, and oceans get Zeihan’s attention.

He uses ancient Egypt to illustrate a great balance of transport. The reliable water and rich soil of the Nile’s floodplains created near-perfect farming conditions, and the Nile itself allowed easy travel and trade throughout the valley. Combined with impenetrable desert borders, this geography “was one of the few places in the world where there was enough water to survive, and enough security to thrive.” Because of that, the “geography nearly guaranteed that the Egyptians would be on the road to civilization.” He gives us a quick run through Egyptian history to tell a story of that road, beginning with the settlement of the area about eight thousand years ago, consolidation into a single kingdom more than five thousand years ago, and then stagnation as the increasingly centralized government devoted more labor to monument building rather than technological progress, eventually being conquered by seafaring people seeking to rule the Mediterranean. 2

To escape our pre-civilization/hunter-gatherer days – Zeihan refers to this as “when life sucked” – the mechanism that he identifies is basically a typical economist’s story. Sedentary agriculture as invented by the Egyptians and other ancient cultures became a transformative technology, letting populations grow and devote labor and resources to non-farming purposes. From this, we got specialization, increased production, trade (particularly where there was easy transportation – population centers were always near water) and capital formation in a self-reinforcing cycle. For thousands of years after this transformative technology was introduced, incremental improvements in agriculture and other areas followed, but “a robust, secure, and sustainable food supply” was the base of any civilization.

This cycle accelerated when we harnessed a couple of new packages of technologies over the last six-hundred years. He lumps the source of much progress together with the terms deepwater navigation and industrialization. The first is everything needed to sail the seas, from shipbuilding capabilities to compasses to weapons. Industrialization is exactly what you’re thinking of. He simplifies it as the combination of labor and capital with higher-output energy sources like oil and coal to put productivity on steroids.

Zeihan gives us a story of the Ottoman Empire entering a prolonged decline as deepwater navigation technologies took off in the fourteenth century. These technologies enabled the European powers (first Portugal and Spain, and then England) to capture increasing shares of trade with Asia, dropping prices in Europe and depriving the Ottomans of much of the income to which they had grown accustomed. Most significantly, they turned “the ocean from a death sentence to a sort of giant river.” Trade became global, but it was still mostly among people with nearby water-based transportation.

Industrialization technologies changed that. Steam and coal brought power to mining and transportation, and along with interchangeable parts, improved manufacturing. Chemical breakthroughs led to fertilizers (improving crop yields), and with more transportation options, more land was brought into cultivation. Improvements in cements in the 1820s enabled larger buildings and infrastructure. These technologies continually improved the productivity cycle that began with agriculture. 3

Zeihan concludes a chapter on America with the “nuts and bolts” of how countries rule the world. “The balance of transport determines wealth and security. Deepwater navigation determines reach. Industrialization determines economic muscle tone. And the three combined shape everything from exposure to durability to economic cycles to outlook.” As we’ll see shortly, he really likes America’s position on all of these factors. But first, we need to understand the other analytical tool that informs Zeihan’s model.

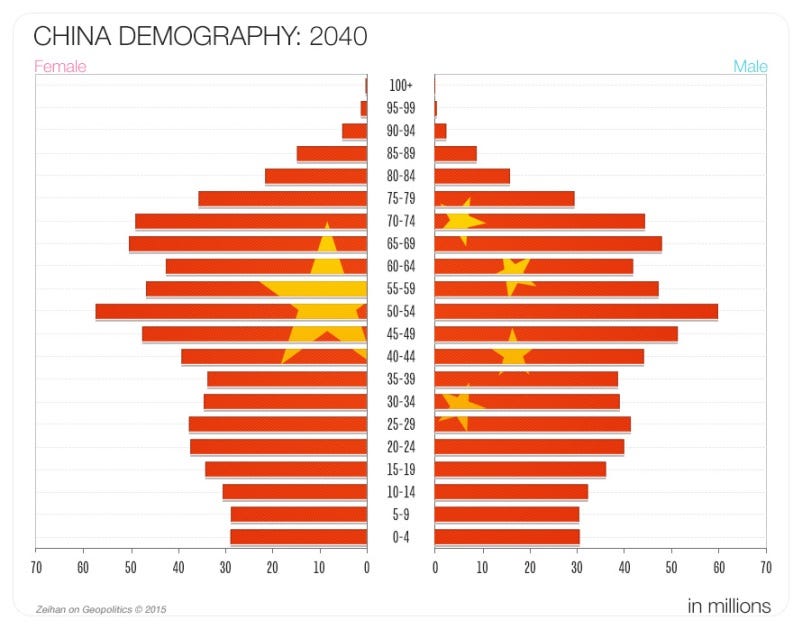

We’ve probably all heard that demography is destiny. Zeihan’s model doesn’t quite go that far, but he’s a big believer in the importance of it. “Marry demographics with geopolitics and you have a series of powerful tools for predicting everything from political instability to economic outcomes.” The Accidental Superpower is filled with country-specific charts that look like this:

These population pyramids break a country’s population into five-year cohorts by age and sex. Notice the massive male/female imbalance at the top – an effect of WWII on these cohorts. A healthy population looks more pyramid like, gradually losing people over time. A demographic disaster is top-heavy. Here’s what China will look like in 2040:

While China’s plummet in birth rates is heavily influenced by its tyrannical one-child policy, Zeihan attributes declining birth rates generally to the move away from farming and toward industrialization and urbanization. Instead of kids being assets on the farm, in the cities they’re financial liabilities, so we should expect fewer of them. To Zeihan, the demographic pyramids (or less attractive shapes) that result from evolving birth patterns affect economic growth in an industrialized world in basically the same way that rivers affect it in an agricultural one.

He thinks of our lives as having some general stages for purposes of economic activity. While we’re kids, we’re a liability in industrial societies; they pay to educate us, and we don’t produce much. While we’re starting in our careers, we “are massive consumers, massive borrowers, and anemic savers.” Zeihan says that “most of our economic growth comes from [these people’s] debt-driven consumption.” Later in our careers, we’re contributing capital to companies and governments with our increased investments and taxes, as our expenses have shrunk and earnings have increased. In old age, we’re liabilities again, but there aren’t as many people as we climb that demographic pyramid, and those of us who remain have our own resources to draw upon, so the societal burden should be easier.

Based on these stages, he says that we should have expected tremendous growth “just as the Cold War ended” due to the “mass of young workers” across the rich world.

We didn’t just get tremendous economic growth though – we got “magical” results, but they were based on a one-time confluence of factors that “overwhelmed the normal rule that lots of twenty-and thirty-somethings make for an expensive-capital environment.” What were these one-time accelerants?

He identifies the peace dividend – cuts in military spending that allowed capital to be put to more productive uses – as one such change, along with the emergent dominance of the US dollar, particularly boosted by Russian demand thanks to the collapse of their currency, and a later boost in demand thanks to the East Asian financial crisis. With the Europeans’ decision to eliminate national currencies (agreed upon in a 1992 treaty, with the Euro to be introduced in 1999), they became relatively unattractive, and the Euro itself (an “unprecedented experiment in pan-government planning”) was too risky. Many holders of European currencies switched to the US dollar, such that between 1994 and 2002 (“when the euro finally got some traction and the surge dialed back”) there was a $2 trillion increase in the money supply. Zeihan also points to a collapse in commodities prices influenced by the elimination of Russian demand, but continued Russian production of oil and other commodities, followed by a collapse in demand thanks to the East Asian financial crisis.

This story of capital coming to the West (“allowing consumption-driven growth not simply to soar, but to explode”) is one of chance world events. However, the story of capital coming from the Boomer cohort is one of demographics. By the 2000s, they’re the mature workers of Zeihan’s four stages described above – and as the bulge in the demographic pyramid, they started flooding the world with capital. Accordingly, “The cost of credit plummeted to levels never before experienced.” Zeihan suggests that developed-world demographics are the cause of booms in places that haven’t been well-developed, from Southern Europe to Brazil, Russia, and India. But he says it’s quickly coming to an end; Boomer savings into stocks and bonds will be moving to low-risk instruments and then turning into withdrawals rather than savings, and the cohort behind them is too small to replace all of that capital. And it’s a worldwide phenomenon:

In every single developed country there is currently an American-style population inversion between the about-to-retire and the about-to-be-mature-workers age groups. Japan’s Boomers bulge is a decade older than the American equivalent, while Spain’s is roughly fifteen years younger. Everyone else falls somewhere in between. It dictates a period of chronically low growth and high credit costs, just not on precisely the same time frame.

The undeveloped world is that way because it can’t self-fund, so without foreign capital, their growth will come to an end. In sum, the 1990-2005 period of high growth and easy capital was a historical anomaly; “the post-Cold War financial flight was a once-in-a-generation event” and the demographic bulge that coincided with it won’t come around again for decades, if ever. 4

2: America’s incredible advantages

As noted above, Zeihan really likes America’s position in the world. He likes its demographics (relative to other developed countries) and loves its geography.

Taking the population question first, in America, “the demographic inversion is only a temporary development.” America is younger than the rest of the developed world, as it urbanized later and its enormous size made having kids easier despite that urbanization (i.e., the suburbs exist). This makes the demographic crunch a single-generation issue, as the Millennials are a huge cohort. And even if they weren’t, America assimilates immigrants more easily than other places – Zeihan attributes this to it being a “settler society” – which can help with demographic problems. The rest of the developed world doesn’t have similar cohorts following their massive Boomer and Gen-X analogues. Accordingly:

While the American financial world will be past its period of maximum stress by 2030, for the rest of the world 2030 will simply be another year of an ever-deepening imbalance between retirees and taxpayers, with smaller and smaller generations coming up the ranks generating less and less growth. For the developed world beyond the United States—and even large portions of the developing world—chronic capital poverty and permanent recession will be the new normal from which there is no return.

Together with America’s Millennial-led growth and abundant energy (there’s a chapter explaining how shale is a done deal that, as of the mid-2014 writing, already made America the world’s largest energy producer 5), by 2030 Zeihan sees it as practically the only country with an economy worth noting.

Anyone who is familiar with American geography should see the argument that’s coming about that aspect of Zeihan’s model. Isn’t the Mississippi River a pretty big deal? And those oceans on the east and west coasts seem like nice borders. Indeed, while he gives us many reasons why there was always going to be an American superpower, geography is central to his story. He has lots to say about America’s internal river systems, farmland, and other geographic features. What mountain barriers exist are apparently better than in other countries in terms of allowing internal transport; the Rockies have major passes, several of which have large cities within them, and the easiest pass in the Appalachians featured America’s first National Road, 130 miles of buried logs that linked two rivers, and thus the east coast with the best farmland in the world.

As we saw with his exposition on the Nile, Zeihan puts a lot of emphasis on the value of river systems. He argues that America’s waterway network alone should be sufficient for “global dominance.” The numbers he provides in support of this point are impressive. For example, “the Mississippi is only one of twelve major navigable American rivers. Collectively, all of America’s temperate-zone rivers are 14,650 miles long. China and Germany each have about 2,000 miles, France about 1,000. The entirety of the Arab world has but 120.” He praises US barrier islands that mitigate oceanic destruction and effectively create another river system, as well as the fact that the river system is an actual network. All of this gives America more internal waterways than the rest of the world combined. Thus, we get cheap transportation for “Nebraska corn or Tennessee whiskey or Texas oil or New Jersey steel or Georgia peaches or Michigan cars,” enabling savings that “can be used for whatever Americans (or their government) want, from iPhones to aircraft carrier battle groups.” America doesn’t have to spend on artificial infrastructure, like German roads and rails, but when it does, the competition from the rivers keeps transport costs low.

Cheap internal transportation has other benefits. “It’s a recipe for small government and high levels of entrepreneurship,” as small government keeps taxes low, leaving people with plenty of capital. Some people may think of the American consumer with disdain, but it isn’t a new phenomenon. Zeihan points out that America has been the world’s largest consumer market “since shortly after the Civil War.”

His observation about a robust food supply forming the base of any civilization bodes well for America, which apparently has the largest connected stretch of quality farmland in the world (the Midwest), the value of which is exponentially increased by the fact that it overlaps with so many of these amazing river systems. It isn’t just the Midwest that he gushes over. California’s Central Valley and the Sacramento River, and Washington and Oregon’s farmland with the Columbia and Snake Rivers get praise. The only major farmland more than 150 miles from a navigable waterway is some of the Great Plains near the Rockies.

Zeihan provides a reminder that national security is actually a thing, and that at its most basic level, it’s about protection against invasions. It was something of a shock reading about America’s land borders in that context. “As Santa Anna discovered during the Texas Independence War, there is no good staging location in (contemporary) Mexican territory that could strike at American lands.” And, “Canada’s border with the United States is much longer, more varied, and even more successful at keeping the two countries separated,” thanks to mountains and thick forests over much of it. The mid-continent lands are much more connected, but Zeihan frames these Canadian areas as basically American; they’re physically separated from Canada’s core eastern provinces, so trade with them is weaker than with the closer American states.

Then there are the oceans. As much as Zeihan loves deserts for protection, he loves oceans more (particularly in a post-World War II world; more on that below). We get a story about the War of 1812 nearly splitting America into three when the British attacked Baltimore. America learned about “strategic vulnerability and sea approaches,” as the attack “on Baltimore—indeed, the entire war effort—would have been impossible without launching grounds in Canada and the Caribbean.” American foreign policy since then can be understood with respect to this lesson. Zeihan cites it as inspiration for America’s steps to make its ocean borders truly impenetrable, such as working to sever Canada from Britain, and the imperial-era acquisitions of Alaska, Hawaii, Midway, Puerto Rico, and de facto control of Cuba (preventing enemies from cutting off Mississippi River-based trade from the rest of the world).

There’s more to Zeihan’s being awestruck by America than his analysis of its balance of transport advantages. He argues that America has been the world leader for agriculture, technology, finance, and industry since the Civil War, and runs through a litany of reasons for its preeminence:

-

America is like a continent-sized island (because of its effective land borders), which is always going to be a more natural naval power than a more landlocked country.

-

Cities such as Pittsburgh, St. Paul, and Tulsa are effectively ocean ports, thanks to the extensive navigable waterways.

-

Its actual ocean ports are bound to outnumber and outclass the rest of the world, given America’s ideal natural harbors with deep passages, friendly land to back it up, and barrier islands (compare his comment on Africa, which has 16,000 miles of coast, “but in reality it has only ten locations with bays of sufficient protective capacity to justify port construction” with one on Texas, which “alone has thirteen world-class deepwater ports, only half of which see significant use, and room for at least three times more”).

-

Significant populations reside on two oceans, preventing the world from being able to export recessions to America (because trade can shift to Europe if Asia is in recession and vice versa).

-

It industrialized relatively easily, thanks to its network of towns that were already connected by these river systems and “164,000 miles of track by 1890.”

-

It has “the world’s highest capital base” accompanying “the lowest need for that capital.”

Zeihan takes a fair amount of criticism from people who say he’s too starry eyed about America. If you don’t already see where these criticisms are coming from, consider passages like this:

The net effect is that the United States now has a multilayered defense of the homeland before one even considers its alliance structure, its maritime prowess, or the general inability of Eurasian powers to assault it.

Which brings us to the final point about why the United States is nearly immune to rivals.

There is no one who is capable of trying.

Or like this:

Even catastrophic losses abroad would never actually harm the base of American power, rooted as it was in the charmed nature of American geography. If Britain lost its empire, it was reduced to secondary-power status. If the Maginot Line were breached, France would fall. If the Americans lost every scrap of land they held internationally, they would still be the most powerful country in human history.

We all know how much more America spends on security than the rest of the world. But when Zeihan talks about other countries’ nonexistent capabilities of assaulting America, he’s not just talking about troops – he’s talking about naval capabilities. Apparently, powerful navies are rare. There haven’t been that many naval powers in world history for a simple reason: “What good is a small task force that can reach around the globe if a foe can simply roll across your frontier with his tanks?” To give an idea of the security that this affords America, Zeihan notes that the only successful across-ocean/continental-scope invasion in world history was pulled off by America, not against it.

This has largely been a summary about wealth creation so far, but The Accidental Superpower is a story about a worldwide disorder that will follow from America’s disengagement from the world. To understand that prediction, you need to know what created and upholds the current world order. For Zeihan, that takes us back to Bretton Woods.

3: Bretton Woods

Zeihan explains World War II in a few pages, the message of which is America’s near invincibility. Some of his assertions may have been a surprise to people at the start of the war, and they certainly made me pause (“Because of American participation the war’s outcome was never in doubt”), but the story he tells about its result are convincing. He cites America’s 6,800 vessel navy at the end of the war (up from less than 400 at the war’s start), over 1,000 of which were “major surface and submarine combatants,” and the sunken remnants of every other major naval force, other than the UK’s, which itself needed American support to operate outside of Europe. The result “was the single greatest concentration of power that the world had ever seen.” When the war was won and America was left standing as the undisputed heavyweight, what would it do?

American empire was rejected out of an unwillingness to have a forever-war of occupation that would have been impractical to wage against the Soviets. Instead, America offers a deal that is “one of the great strategic gambits in history.” The deal offered benefits not only to England, France, and the Allies, but also to Japan and Germany that they couldn’t have even hoped to achieve had they won the war.6 Zeihan refers to this deal as “free trade” and “Bretton Woods,” based on the New Hampshire town in which the Americans dictated its terms to the Allies in 1944. It would let everyone sell into the best and last market in the world, with their commerce protected by the world’s only real navy, and all that America asked in return was the provision of cannon fodder against Soviet invasions. That may not have been such a big ask, as they may have lost their independence to such invasions without American assistance anyway. The deal was offered in pursuit of the strategic goal of containing the Soviets, presumably to avoid having them directly threaten Americans.

American foreign policy comes off looking surprising competent through Zeihan’s story. In describing the history of Bretton Woods, he runs through some key participants and highlights the benefits of their membership. India, hurting the Soviets in South Asia; Sweden, hurting them in the Baltic; Argentina and Egypt, limiting their influence in South America and the Middle East; and most significantly, China, depriving them of their best ports. Why did America fight in Korea and Vietnam? To demonstrate the value of the security guarantee component of the Bretton Woods regime (“if the Americans proved unwilling to engage the Chinese in Korea, then was their security guarantee for the Germans against the Soviets really worth what they said it was?”).

While Bretton Woods was America’s plan, presumably to benefit America, it had some nice side effects for the world. Zeihan credits it with leading to peace between former enemies, a new era of cooperation (France and Germany forming the EU; Sweden and the Netherlands focusing on trade; a free-trade network in Southeast Asia), and ending colonialism:

The Suez Canal Crisis of 1956, which concluded with the Americans intentionally and publicly humiliating the English and French by withdrawing post–World War II recovery aid and spearheading international opposition, was the most visible manifestation of the Americans driving home just who was in charge. Over the next generation every significant European colony got its independence. The Americans didn’t take any of them over, because it didn’t need them. Its goal was to break the European hold over the world and make the European powers dependent upon the Bretton Woods system.

This world of free trade is essentially the only world we’ve ever known. We’ve been spoiled. “After eons of struggling for economic growth and physical security, both were now guaranteed. Instead of wealth and security being the goal, they became the starting point.” Germany, Korea, China, and others have “redesigned their economic systems to take full advantage of a world of risk-free international shipping and easy American market access. These places, and many more, are now dependent upon the continuation of the current system for their economic wherewithal. And even those that expanded their international footprint more modestly lack the military capacity to protect their overseas trade networks. Most lack the ability to patrol much more than their own coastlines, if even that.”

Guess who doesn’t need this system any longer? Zeihan notes that America has been retreating from a commitment to global free trade for years and gives us some reasons why we should expect this trend to continue. For America, it was a political strategy, not an economic one. He notes the massive costs of the American military, as well as America’s $700 billion trade deficit, and calls these costs that were easier to justify in the context of the Cold War. (Yes, he refers to a trade deficit as a cost. It’s not.) Nonetheless, the free trade system is going to be upended:

The looming crisis of the contemporary system is actually pretty straightforward. Everything that makes the global economy tick—from reliable access to global energy supplies to the ability to sell into the American market to the free movement of capital—is a direct outcome of the ongoing American commitment to Bretton Woods. But the Americans are no longer gaining a strategic benefit from that network, even as the economic cost continues. At some point—maybe next week, maybe ten years from now—the Americans are going to reprioritize, and the tenets of Bretton Woods, the foundation of the free trade order, will simply end.

4: The Disorder

The energy abundance mentioned above shouldn’t be overlooked. Zeihan argues that America will move from being “the world’s largest energy importer for nearly all of the past thirty years” to no longer really participating in the global energy trade. He links that to the old alliance system: America protected energy to enable trade and ensure the Bretton Woods alliance. But now that the Cold War is over, America doesn’t need the alliance, and doesn’t even need the world’s energy itself. It just hasn’t really taken note of the alliance outliving its purpose.

If you’re a fan of our free-trade world, then you should probably pause to ask some questions about its potential demise. Zeihan notes that nearly all participants in Bretton Woods have suspended military activity (other than in connection with American efforts), allowing small countries to exist and even thrive (citing Slovakia, Macedonia, Korea, and “a host of Sub-Saharan African states”), allowing former rivals to focus on development (citing the EU and its expansion into Southern and Central Europe, and Russian firms being able to borrow at favorable rates despite a history of sovereign defaults and fraud), and leading to mass industrialization. In short, “The last seventy years have been incredible.”

It’s not just global trade that has delivered these benefits. Capital availability driven by demographics was a big part of this story. Here, Zeihan gives us a metaphor about mature workers turning into retirees. The flow of contributions into a mature worker’s accounts stops when he stops working, and he starts drawing on his government or private pension, which “is the financial equivalent of hiking up a mountain for weeks only to reach the top and leap off the cliff.” He sees early Boomer retirements as signaling massive capital availability, switching to scarcity once “the majority of the 200 million developed-world Boomers jump off the financial cliff into their Boca and Barcelona condos.”

Peak capital availability will happen over the next few years (through 2024), the aftermath of which will be brutal. More expensive credit for individuals and governments, plunging consumer activity from that and fewer young workers, increased government spending on healthcare and pensions even as the decrease in mature workers guts its tax revenues (he doesn’t seem to consider that fewer fifty-year olds may mean fewer high-income taxpayers, but if there are many more young workers, revenues could actually increase), slower technological progress, lower standards of living. Without America to protect shipping, insurance costs will rise, and transport will become erratic (but North American energy will flourish in this world, with political stability and ease of transport across the continent decoupling it from world prices).

If America withdraws, it “will simultaneously trigger economic and energy crises for Europe, East Asia, and South Asia and financial and security crises for the Persian Gulf states.” Zeihan’s positive scenario for this world involves mere austerity and Greece-like scenarios, and is premised on countries getting along peacefully, but he doesn’t expect that. “It is far more likely that they won’t [get along peacefully].” Instead, his expected and pessimistic scenario should be terrifying for those outside of the American bubble:

Countries far removed from supplies of food, energy, and/or the basic matrix of inputs that make the industrialized world possible will face the stark choice of either throwing themselves at the mercy of superior local powers or throwing what force they can muster at the resource providers. In their desperation, many will realize that American disinterest in the world means that American security guarantees are unlikely to be honored. Competitions held in check for the better part of a century will return. Wars of opportunism will come back into fashion. History will restart. Areas that we have come to think of as calm will seethe as countries struggle for resources, capital, and markets. For countries unable to secure supplies (regardless of means), there is a more than minor possibility that they will simply fall out of the modern world altogether.

Zeihan knows how this sounds, but he backs it up with analysis of the dependencies of the modern world, from energy needs throughout Europe (only Norway is self-sufficient) to food requirements throughout the Middle East and assorted other countries. Resource constraints and the population boom that resulted from the green revolution in agriculture in the 20th century have him talking about “The wars of the not too distant future” that will be over “the ability to remain part of the modern world. Or simply to remain.”

While this is hardly cheerful stuff, America’s situation in the Disorder is relatively great. The demographic inversion will affect it, but less so than other places. The American market will still be the largest in the world, and it won’t need the world for energy or food. It isn’t as reliant on international trade as other places, and once the friendly North American-based trade is excluded, it looks even more independent. The net result is America losing interest in global energy and global trade, requiring it to go abroad only to secure its own shipping, which itself is a shrinking share of GDP. “Without global needs or global interests, there is no reason to impose a global order.”

Zeihan sees American disengagement. Other than “a scant handful of strategic and economic allies… America’s primary means of interaction with the international community will be via its special forces and long-arm navy, which will use fast, discrete attacks to eliminate perceived threats or disrupt governments sufficiently unwise to attract the wrong kind of American attention.” Geopolitics will restart.

The second half of The Accidental Superpower is filled with Zeihan’s predictions about what happens if the big thesis is right. Some states will fail, as they don’t have what’s needed to survive (Syria, Greece, Libya). Some will decentralize, as they’re in the same boat, just not as hard up (Russia, China). Some will merely decline, as they have some capacity to address challenges (Brazil, India, Canada). Some will cope (UK, France, Peru, Philippines). A few will join the US as “masters of the chaos,” as they have favorable geographies and other advantages (Australia, Argentina, Angola, Turkey, Indonesia, Uzbekistan).

These predictions include some persuasive analysis of many countries and plenty of speculation to go with it. Zeihan spends a chapter highlighting America’s partners in the chaos to come. At the top of the list are its North American neighbors, and a prediction that Cuba will be pulled back into the American orbit (because a larger power that supported it could cut off trade with the greater Mississippi system – Zeihan’s summary of exactly why America was willing to risk nuclear war in the Cuban Missile Crisis). He also gives some analysis of the geography of South America and how it affects their trading patterns, and of the best European allies for various purposes (Denmark and the Netherlands control access to the Rhine and Baltic Sea, making them valuable allies). He runs through the trade of Southeast Asia and suggests that American cooperation in the area could have a strategic benefit of helping to “keep China and India apart.”

He spends another chapter surveying places that he expects to be left out of the American partnerships to come. Russia is a leading example of a desperate country in this regard. 7 Zeihan’s summary of its challenges is framed by its demographics and its geography, both of which he finds daunting:

Its demographic decline is so steep, so far advanced, and so multivectored that for demographic reasons alone Russia is unlikely to survive as a state, and Russians are unlikely to survive as a people over the next couple of generations. Yet within Russia’s completely indefensible borders, it cannot possibly last even that long. Russia has at most eight years of relative strength to act. If it fails, it will have lost the capacity to man a military. To maintain a sizable missile fleet. To keep its roads and rail system in working order. To prevent its regional cities from collapsing. To monitor its frontier.

To delay its national twilight.

Zeihan provides similar analysis regarding many other countries, including Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Angola, and Iran, before turning to Europe and China. As mentioned in the first paragraph, Zeihan sees collapse coming.

Europe’s problems appear awful. “A continent riven by war is hardly how most of us think of Europe, but that is because the Europe we know has been transformed utterly by Bretton Woods,” which is the only thing that has ever united Europe from a security perspective. Zeihan sees America going away from Europe, and therefore the old conflicts will resume. The result will include countries afraid of an older Germany that faces economic catastrophe (its demographic pyramid is bad, with a rapidly-aging population that will soon retire, and its export-driven economy is in danger), the above-mentioned threats from Russia, “a justifiably paranoid Poland backed by a no longer neutral Sweden,” and a rising Turkey. While Zeihan doubts that each of these problems will lead to wars, “it truly would be stunning if none of them did.”

In singing praises of America, Zeihan noted that its market is still the largest in the world, and will remain that way in the Disorder. What about China? He acknowledges that everyone sees it as the future. Yet he objects to this perspective, comparing it to the same American fears about the rise of the Soviet Union in the Cold War and Japan in the 1980s. His analysis – surprise – is rooted in its awful demographic pyramid (shown above) and geography.

Its geographic disadvantages are apparently numerous. China lacks much in the way of navigable rivers (“the Yellow is not navigable—in part due to its heavy engineering”) and frequent, heavy flooding and droughts on the North China Plain require strong irrigation efforts. The stunted trade that follows from these features – and the mass labor that it takes to make agriculture here work – has traditionally kept China from accumulating capital, much less industrializing. The Yangtze River in central China could provide that capital (Zeihan calls it “China’s sole navigable river”), but it’s seasonal and shallow and mountainous. It contributes to a “fractured nature” of central China that “complicate[s] northern China’s always vexing problem of internal disunity.”

Zeihan references this political unification issue when discussing the southern cities. They have ports, but no rivers, and are backed by mountains. These places historically traded with foreigners, while the northern Chinese haven’t had such easy access. (It’s not clear to me that the oppressive CCP that runs the country now doesn’t have better control over these cities. Hong Kong is off the southern coast, and the CCP’s imminent takeover of it doesn’t seem to be reversing.) Unification also comes up with respect to the interior. These regions are huge and have half the population of the country, but one generality Zeihan comes up with to describe them is “extremely poor.” He cites awful transportation as a cause.

Its historical geographic divisions have apparently held to this day, with the north controlling politics, Shanghai and central China forming an economic core, the south a perennial secessionist threat, and the interior ignored. (This book predates the genocidal campaign against the Uighurs in Xinjiang, though Tibet has suffered its share of atrocities.) Recent unification came about only after America took the threat of Japan away, and its economic rise coincided with its participation in America’s free trade network. With that change, “Instead of being raided for raw materials, China was guaranteed access to global supplies. The endless supplies of cheap labor that the Europeans and Japanese ruthlessly tapped now allowed China to generate its own goods for export, this time with the revenues flowing to the Chinese instead of overseas interests.”

For everyone worried about the rise of China, Zeihan should be reassuring (but to be clear, you shouldn’t worry about other places getting wealthy; when they do so, it’s unlikely to make you poorer). He tells us that its time is coming to an end. In his description of the Chinese economy, the word sustainable would never come to mind. Here’s Zeihan on banking in China:

Loans are available for everything. Want to launch a new product? Take out a loan to finance the development, to pay the staff, to cover marketing expenses, to build a warehouse to store output that doesn’t sell as planned. Find yourself under the burden of too many loans? Take out another to cover the loan payments. The result is an ever-rising mountain of loans gone bad and ever less efficient firms, held together by nothing more than the system’s bottomless supply of cheap labor and cheap credit.

Similarly, “When you don’t care about prices or output or debt or quality or safety or reputation, your economic growth is truly impressive.” Zeihan basically claims that the CCP’s goal is employment and activity, not wealth creation.

About the awful demographic pyramid: “The Chinese call it the 4:2:1 problem: four grandparents to two parents to one child.” With no government pension system and a greater imbalance than even America’s Boomer retirement bulge, the costs to China are enormous, “gutting consumption, and all but making savings impossible.” Zeihan sees that as a bit of a problem since the savings are what enable “the force-fed-finance model” of the exorbitant lending, to say nothing of the cheap labor that enabled it to capture so much of global manufacturing to date.

Should America stop securing sea lanes, China would face an oil crisis. “Almost all of the countries along China’s oil import route are also oil importers. All already have more than enough naval power necessary to interdict supertankers that go somewhere they don’t wish them to. And China dare not risk tangling with even a mid-powered navy out of range of its land-based aircraft because it lacks meaningful blue-water capabilities.” Worse for China, Japan’s navy is very capable, and Taiwan and other islands off of its coast are hostile to it (and are likely to remain American allies on top of that).

5: Many questions, some conclusions

Are people today aware of how deserts and oceans provide security against invasions, how waterways facilitate trade, or how international trade requires protection against adversaries? If America actually does pull back from the free trade world that it shaped after the war, we should expect a lot more attention to questions like these. In the meantime, at least in part due to Zeihan’s influence, I’m seeing more discussion about these subjects. For a (slightly) less-than-book-length preview of them, see Conrad Bastable’s (very funny and entertaining, to say nothing of its informational value) The Full Stack of Society: Can You Make A Whole Society Wealthier? [Full Version], which cites Zeihan at some point. Or if podcasts are more your thing, try Hidden Forces with Demetri Kofinas, who recently interviewed the world-traveling/veteran/writer/investor Radigan Carter and got into Zeihan’s thesis with him (they both agree with it), or any of the many podcasts with Zeihan himself.

If you find Zeihan’s model of power and economic growth to be compelling, then you’ll almost certainly be with him on many of the conclusions that follow from its application. You might also find the model to be more or less useful, but be skeptical of how he applies it. That’s probably a common reaction. At one point, Zeihan mentions that he’s “acutely aware that it’s a great big mess of a world out there, filled to overflowing with complex interactions.”

Where does Zeihan go wrong? In a book that covers everything from the dawn of sedentary agriculture to the present, from the Ottoman Empire to American hegemony, I’m sure there are a few errors. One shouldn’t nitpick though; we should focus on his thesis, his model, and his main predictions. So what about the overall thesis? The main objection I had was the tension between Zeihan’s competing stories of why we get rich. He might not even see that he told competing stories about that.

On the one hand, he sounds like a supply-sider; he talks about moving from agriculture, to internal trade, to specialization, which “moves an economy [8] up the value-added scale, increasing local incomes and generating capital that can be used for everything from building schools and institutions to operating a navy.” This same sentiment shows up when he discusses Egypt’s development path. Aside from expressly mentioning specialization and productivity gains as helping Egypt progress, he blames its stagnation on using resources for nonproductive purposes (“ego projects,” such as “monument construction” or “big piles of rocks,” in contrast to the desirable “technological innovation”).

On the other hand, he sounds positively Keynesian; in discussing our progression from kids to young workers, to mature ones, to retirees, he says “most of our economic growth comes from [young workers’] debt-driven consumption.” Similarly, in discussing the post-Cold War economic boom (and elsewhere in the book), he mentions our “consumption-driven growth” and “consumption-led growth.” I’ve never understood why people find this idea persuasive. Most of us would consume all the things if we could. Economists’ models often start from the idea that we have unlimited demand for goods and services. It’s certainly true that some places have higher consumption than other places, but these places also happen to also have higher production. If the desire to consume actually gave us growth, one supposes that the richest places would be those that wished for it the most. If you say no, it’s the ability to consume that gives the growth , then you’re almost there; the ability to consume is another way of saying that you have already produced value for the world (i.e., you’re a supply-sider too).

It’s particularly jarring to read these recurring references to consumption as the cause of wealth creation from a person who mocks poor uses of resources (“big piles of rocks”) as leading to economic stagnation, and who talks about the cost of capital and the feasibility of various projects (“The lower the cost of the credit, the more options within your reach. It really isn’t any more complicated than that”). In Zeihan’s defense, he acknowledges “three routes a country can take to economic growth: consumption-led, export-led, and investment-led.” (I’m probably an outlier in mocking the consumption-led model as a route to growth. 9) So he’s at least aware that some of us think that some of these routes are better than others, if not necessarily that the consumption-led route is nonsense.

Maybe this objection to Zeihan’s thinking about economic growth is closer to a nit, as I don’t think it invalidates his thesis. However, I do wonder to what extent he overlooks human creativity. Leaders aren’t going to sit back and meekly accept the Disorder if America steps back from its role as a global trade and security guarantor 10. Not many people prefer a world where they have to spend obscene amounts on physical security, and with war and poverty looming in the future if cooperation fails, it seems like world leaders would have an extremely strong incentive to cooperate. He seems to acknowledge this when discussing Asian free trade networks, but the same mechanism could work elsewhere.

The last serious point to make about his thesis is about how it depends on America pulling back from the world. Is that a good idea or not? When I was younger, I wouldn’t have hesitated: I’d have said that we’re throwing tons of money at world security that we don’t have, that we get little in return, and that we should come home. Zeihan’s explanation of the free trade order that America has ensured for decades is the most powerful argument against that perspective that I’ve encountered. I’m not sure if it changes my conclusion, but I’m certainly less confident of it now. I could use more straight talk about what America’s interests actually are with respect to overseas commitments. Radigan Carter puts this in very real terms, asking about a CCP invasion of Taiwan (“a lot of us war veterans [are] more interested in buying a house and taking a hunting trip than reenlisting to defend Taiwan”). For the rest of the world, whether America withdraws may be the defining question of the era.

I also have less-serious questions that may be worth noting. Who are the experts on global affairs and foreign policy? People who pay attention to these things probably see a few recurring names providing analysis, but making the wrong calls over and over again doesn’t seem to hurt certain people’s careers in this field. How many times can a Max Boot-type (to pull one name I’ve seen for years) advocate for war, tell us how necessary it is, and have it turn out contrary to his predictions before we should banish him from wide-reaching platforms? Seeing the lack of consequences for those who make idiotic arguments – in fact, some people seem to inevitably fail upward here, particularly in politics – I might have an inherent distrust of anyone in this field that’s tough to overcome.

Zeihan does much to address this concern. He’s writing for the general public, so he not only writes simply and clearly (demonstrating clear thinking), but also clarifies foundational concepts like strategic interest and economic interest. It’s a refreshing change from listening to national security types on cable news, or even reading the WSJ, where people often don’t bother explaining what they mean when they assert that something is an American interest.

Zeihan writes with confidence, his presentation is excellent, and his appreciation for demographic models and trade as drivers of productivity and wealth creation should be persuasive. Yet I wonder whether his disclaimers about inevitably getting things wrong set us up to discount predictions that turn out to be off the mark, while focusing on those that he gets right. For example, when you admit that you don’t know which particular path China or Germany will follow as they decline, but that any one of a handful of factors that you cite could lead to trouble, it seems like kind of a low bar. On the other hand (and I lean this way), the world is terribly complex – do we really expect narrow predictions about everything?

Then there’s something like the CNBC effect. Why did stock prices increase/decrease on any random day? Intelligent people don’t think like this, but there is demand for “analysis” of such questions. Some people go so far as to say that it’s the same reason that Wall Street provides market research; the demand is there, so someone will sell it. It reminds me of a story I heard from Reason columnist Ron Bailey. When he was selling The End of Doom , an agent asked him to change his thesis, because optimism doesn’t sell, whereas doom could make him a very rich author. I very much doubt that Zeihan created his analysis in order to arrive at the conclusion that we’re going to see a global Disorder over the next decade, 11 but once you see structural incentives it’s hard to banish them from your thoughts (see also, Meditations on Moloch).

Finally, Nassim Taleb’s question nags at me. I first heard of Zeihan in connection with a finance podcast, and couldn’t help but consider the implications of his thesis for my own portfolio. 12 Taleb wrote in Skin in the Game , “Don’t tell me what you ‘think,’ just tell me what’s in your portfolio.” If Zeihan’s personal portfolio is, let’s say, all-in on American Treasuries and equities (or even more committed to his thesis, such as by being short Chinese equities), that may say more than his excellent book already does.

1 The ellipsis is a favorite Zeihan tick. Having listened to him on more than a few podcasts since picking up the book, his voice comes through the pages. It reads like you’re old friends and he’s telling you the way it is over beers. For example, in discussing the effects of the Bretton Woods system, Zeihan notes the creation of “banking empires in… Ireland and Iceland,” with a footnote saying “Seriously. WTF?”

2 After telling this story, Zeihan claims that once they were conquered by the Romans, Egypt was “not independent for a single day until the collapse of the European colonial era after World War II.”

3 For a deeper dive into this than Zeihan gives, see How Innovation Works , by Matt Ridley. These two tell very similar stories about wealth creation and what it is that gives us the modern world. Zeihan mentions the productivity cycle progressing through incremental improvements in technology, and suggests that this cycle is the source of economic growth. That’s essentially the thesis of Ridley’s latest book.

4 Zeihan gives some interesting stories about places trying to deal with the demographic inversion, from Japan’s extensive use of feeding tubes in the elderly, to Russia’s subsidizing births from 2006 and the resulting rise in kids left in orphanages, to Sweden’s generous parental-leave policies that he blames for their young female population suffering high unemployment and underemployment.

5 Zeihan’s follow-up book to The Accidental Superpower – 2017’s The Absent Superpower: The Shale Revolution and a World Without America – goes even more in-depth to the wonders of America’s energy situation. If you don’t know much about hydrocarbons (I certainly didn’t before reading Zeihan), these books will give you a detailed look at them.

6 Apparently Germany and Japan would have found it to be unbelievable. “The primary reason Germany and Japan had launched World War II in the first place was to gain greater access to resources and markets. Germany wanted the agricultural output of Poland, the capital of the Low Countries, the coal of Central Europe, and the markets of France. Japan coveted the manpower and markets of China and the resources of Southeast Asia. Now that they had been thoroughly defeated, the Americans were offering them economic access far beyond their wildest prewar longings: risk-free access to ample resources and bottomless markets a half a world away. And “all” it would cost them was accepting a security guarantee that was better than anything they could ever have achieved by themselves.”

7 It gets even more attention in his follow-up books, The Absent Superpower and Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World(2020).

8 On the economy , I have a hard agreement with Allen Farrington on this: “one day people will stop referring to ‘the economy’ as if it is a noun, and will stop saying ‘it’ faces ‘risks’. it will be a good day.” If something in here suggests otherwise, that just goes to show how easily we slip into common usage when talking about this.

9 But I’m going to continue mocking it. Mere demand doesn’t generate real goods and services, investment does. I highly recommend Allen Farrington on both this point and clear-eyed looks at economic growth generally.

10 I lean toward Zeihan’s perspective here, thinking that it’s more likely a question of when America steps back from this role.

11 He kicks off the book with a statement about where he’s coming from that helps establish his credibility on this point. “I’m an unflinching supporter of free trade and the Western alliance network, seeing the pair as ushering in the greatest peace and prosperity this world has ever known. Yet geography tells me both will be abandoned. I prefer small government, believing that an unobtrusive system generates the broadest and fastest spread of wealth and liberty. But demography tells me an ever larger slice of my income will be taken to fund a system that is ever less dynamic and accountable. I am not required to savor my conclusions. This isn’t a book of recommendations on what I think should happen. This is a book of predictions about what will happen.”

12 I ultimately sold a bunch of non-US equities, and was heavily influenced by Zeihan’s books in doing so.