Your Book Review: The Future Of Fusion Energy

[This is one of the finalists in the 2022 book review contest. It’s not by me - it’s by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done, to prevent their identity from influencing your decisions. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked - SA]

Introduction

Fusion is the power which lights the stars. It is the source of all elements heavier than hydrogen in the universe. Wouldn’t it be great if we could use and control this power here on Earth?

I predict that we will get fusion [1] before 2035 (80%) or 2040 (90%). I am a professional plasma physicist, a fusioneer if you will, so I probably know more about this subject than you, but am likely to overemphasize its importance.

The Future of Fusion Energy is the best introduction to fusion that I know. I can confirm that the information it contains is common knowledge among plasma physicists. My parents, who are not physicists [2], can confirm that it is accessible and interesting to read.

Things are changing fast in fusion right now, and The Future of Fusion Energy is already out of date in some important ways. I will summarize our quest for fusion as it is portrayed in the book, describe what has happened in the field since 2018, and make some predictions about where we go from here. The predictions are my own and do not reflect the opinions of Parisi or Ball.

Why Don’t We Have Fusion Already?

There is an old joke:

Fusion is 30 years away and always will be.

What happened? Why has fusion failed to deliver on its promise in the past?

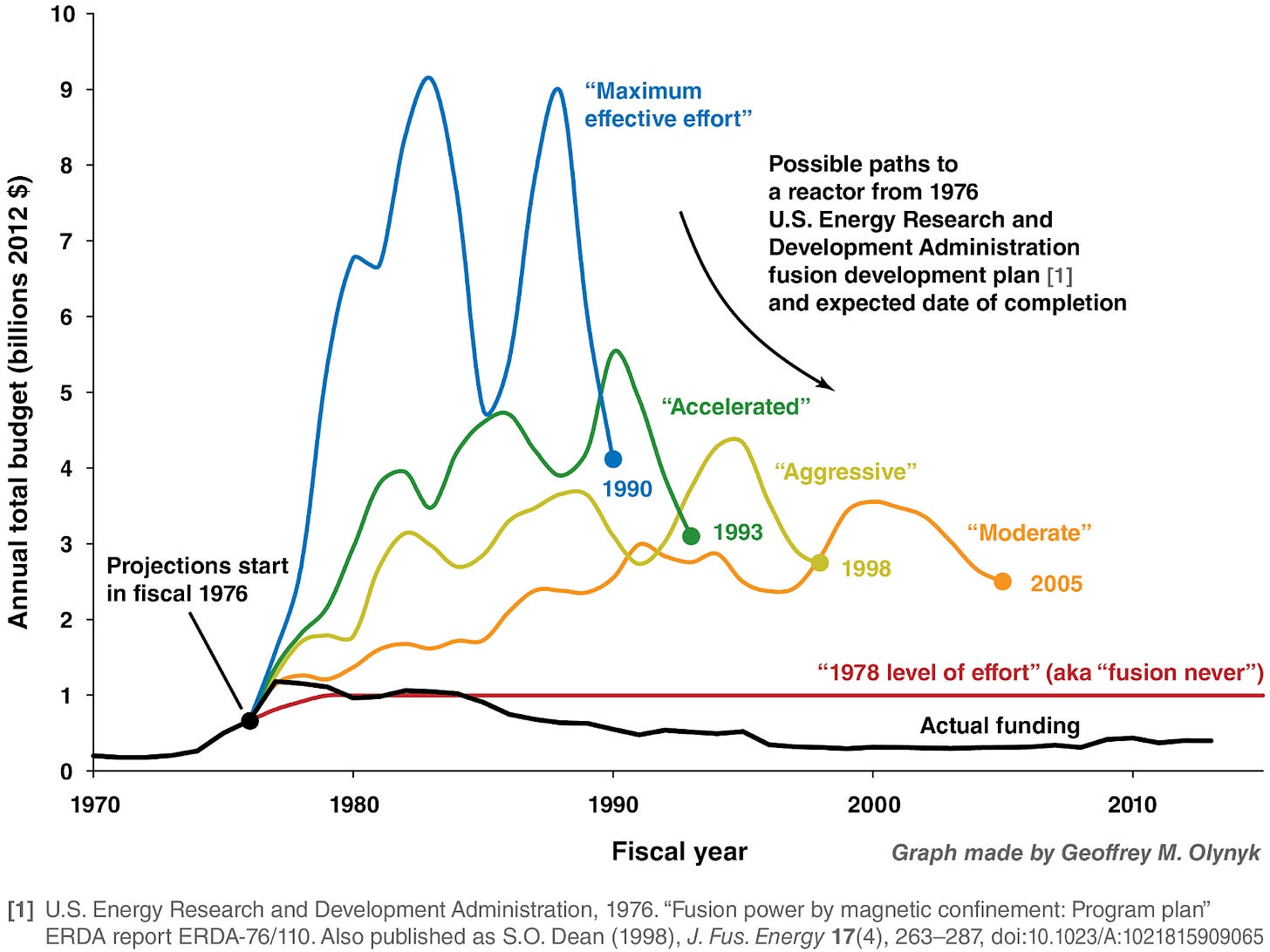

By the 1970s, it was apparent that making fusion power work is possible, but very hard. Fusion would require Big Science with Significant Support. The total cost would be less than the Apollo Program, similar to the International Space Station, and more than the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. The Department of Energy put together a request for funding. They proposed several different plans. Depending on how much funding was available, we could get fusion in 15-30 years.

How did that work out?

Along with the plans for fusion in 15-30 years, there was also a reference: ‘fusion never’. This plan would maintain America’s plasma physics facilities, but not try to build anything new.

Actual funding for fusion in the US has been less than the ‘fusion never’ plan.

The reason we don’t have fusion already is because we, as a civilization, never decided that it was a priority. Fusion funding is literally peanuts: In 2016, the US spent twice as much on peanut subsidies as on fusion research.

Fusion Basics

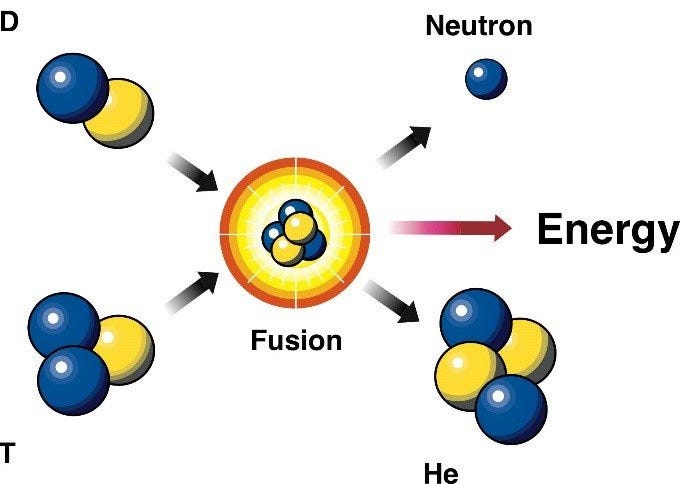

Fusion involves ‘burning’ lighter elements to make heavier elements.

The sun gets its energy by burning hydrogen into helium. We are trying to do something similar [3].

The easiest fusion reaction is burning deuterium and tritium to make helium. Deuterium is an isotope of hydrogen with one proton & one neutron and tritium is an isotope of hydrogen with one proton & two neutrons. Helium has two protons and two neutrons, so one free neutron is produced by the reaction as well.

Figure 2: The D-T fusion reaction.

Figure 2: The D-T fusion reaction.

This reaction can be written as:

12D +13T 24He +01n .

The subscript is the number of protons that each element has and the superscript is the number of protons + neutrons [4]. Both of these numbers are conserved: if you add up the total superscript on the left, it must equal the total superscript on the right.

Several other fusion reactions are sometimes discussed as alternatives to deuterium-tritium fusion. All of them are at least several times more difficult, so they are unlikely to be the first fuel we use to get fusion. Maybe someday we’ll switch to deuterium-deuterium fusion or something else, but for now, the emphasis is on what’s easiest.

What do you need to get a fusion reaction going?

Think about the chemical reactions in combustion. You need to get the fuel to a high enough temperature, and then chemical reactions occur that release energy. Fusion is similar, but with much larger temperatures and energies. Combustion occurs at a temperature of about 1000 Kelvin [5] and each reaction releases about 10 electron volts of energy. Fusion occurs at about 100 million Kelvin and each reaction releases about 10 million electron volts.

Along with a high enough temperature, you also need to have a high enough density and confinement time. Density is important because fusion requires a collision between a deuterium nucleus and a tritium nucleus. When the density is higher, stuff is more likely to run into each other. We also need to confine the fuel and the energy long enough for these collisions to occur. We don’t want the particles to leave the reactor without fusing. If the energy leaks out too quickly, then the fuel will cool down too quickly to burn.

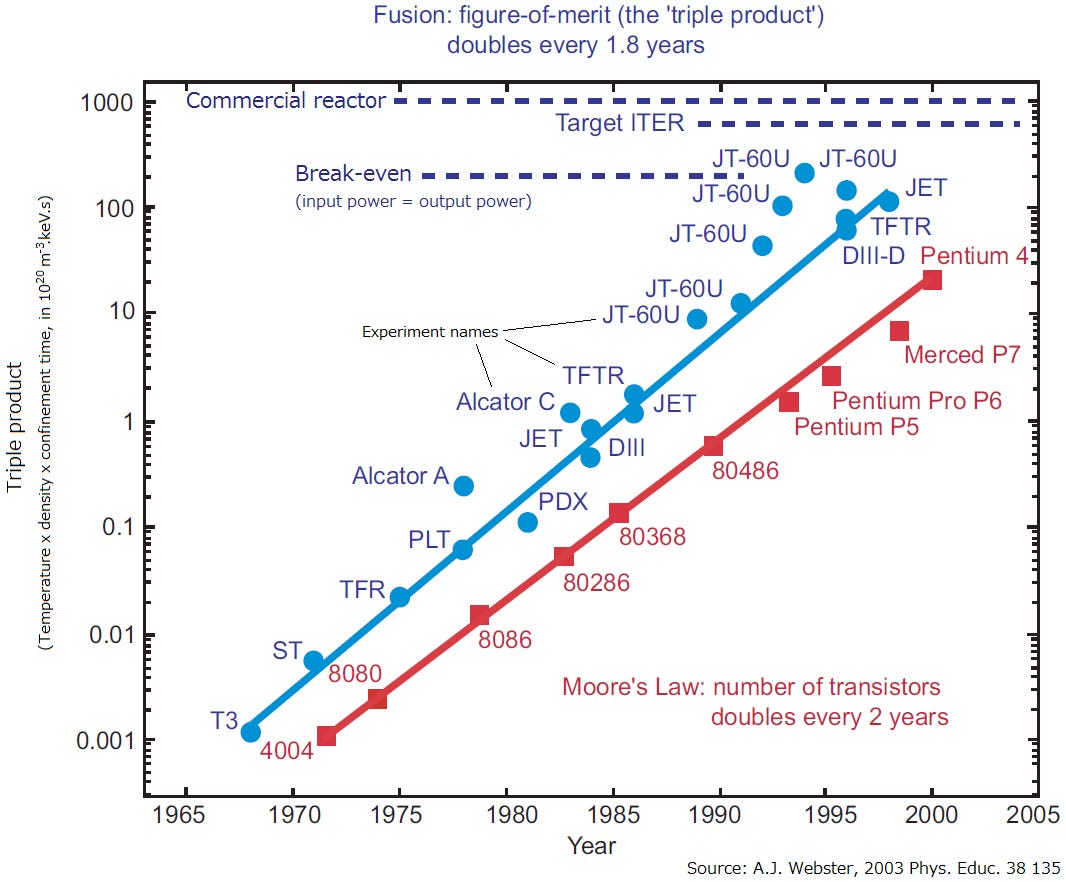

Multiply these three quantities, density, temperature, and confinement time [6], to get the plasma triple product. Lawson’s criterion states that, if the triple product is high enough, then you will get fusion.

We also measure the success of fusion using Q. Q is the ratio of the amount of energy you put into the fuel to the amount of energy produced by fusion. News articles often focus on Q=1, or ‘scientific breakeven’ [7], when you get as much energy out of the fuel as you put in. Other significant milestones are Q=5, ‘burning’, and Q=∞ , ‘ignition’, when the fusion sustains itself without any external heating.

Q is entirely determined by the triple product. To get Q=1 for D-T fusion, you need a triple product of 51021 keV s / m3. Getting a large Q is the goal of fusion science. Getting a large triple product is how we achieve that goal. We can use the triple product to measure progress towards fusion.

Have We Made Progress?

How much progress have we made towards fusion?

The fusion triple product has grown exponentially. It has doubled every 1.8 years, which is even faster than Moore’s Law. The best triple product we’ve gotten is five orders of magnitude better than what we started with in 1970.

But wait. This data only goes up to 2000. If we extrapolate the trend line, we would have built a commercial fusion reactor in 2005. The world is not awash in fusion energy, so this trend clearly did not continue. There has been little progress towards a larger triple product since 2000.

Why did this trendline stop? Why do I think that this is about to get started again?

I will answer these questions, but first, a few words on how we’ve made progress so far.

Plasma Basics

Fusion occurs at such high temperatures that everything is ionized: The electrons and nuclei cannot stick together as atoms and instead move independently. Matter in this state is called a ‘plasma’ [8]. Plasma is by far the most common state of matter in the universe. Stars are made of plasma, as well as the low density matter in the space between stars.

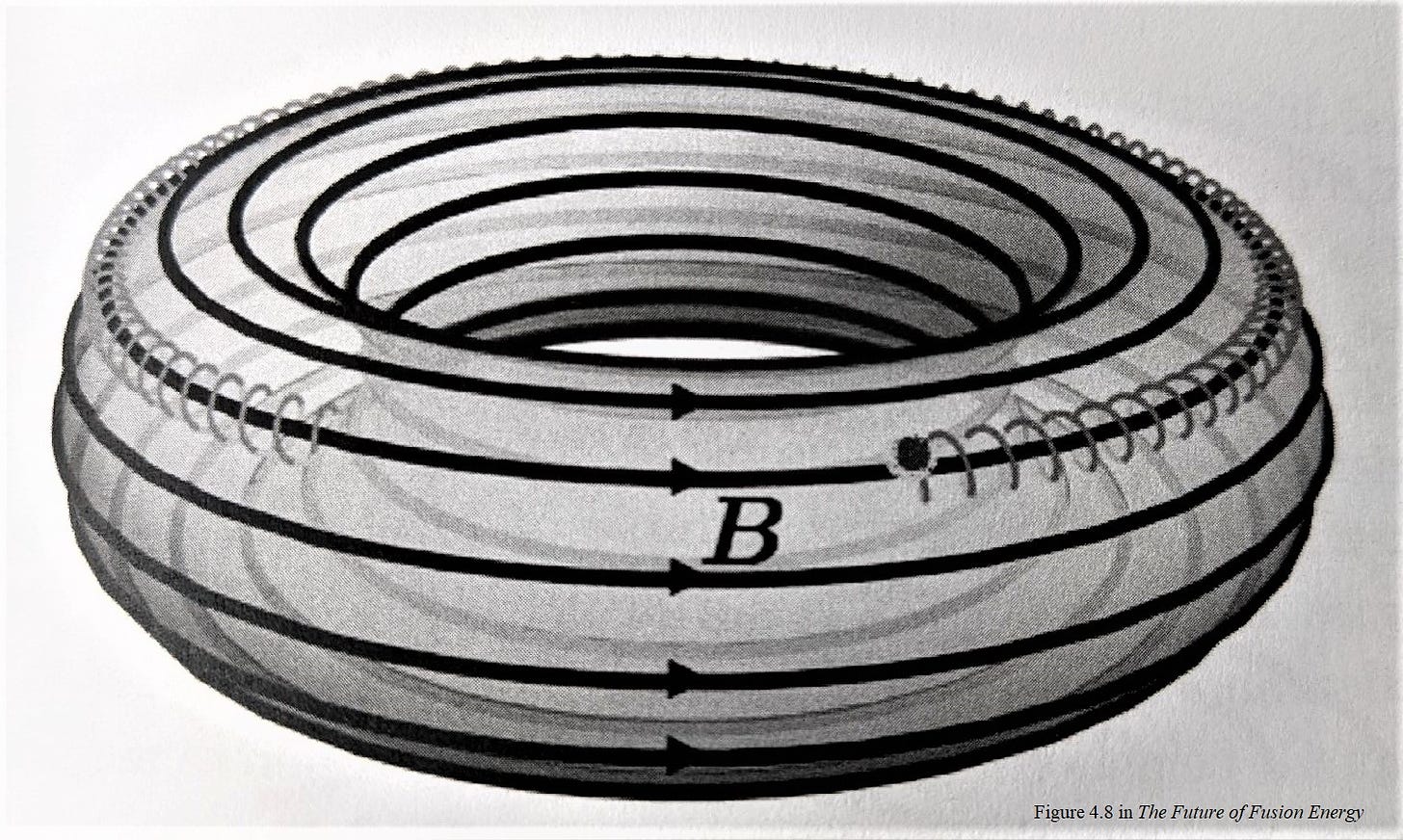

When a fusion plasma comes in contact with anything solid (or liquid or even gas), either the solid will vaporize or the plasma will cool down. Both of these are very bad for achieving controlled fusion on Earth. We can’t just put our fusion plasma in a container.

How do we bottle the core of the sun?

With a magnetic field. The electrons and ions in a fusion plasma are charged. Charged particles spiral around magnetic field lines and will not move freely perpendicular to the magnetic field. This confines the plasma in two dimensions. To confine the plasma in the third dimension, loop the magnetic field around in the shape of a doughnut [9]. The particles can move around the doughnut, but stay confined within it.

Figure 4: A charged particle spiraling around a doughnut-shaped magnetic field.

Figure 4: A charged particle spiraling around a doughnut-shaped magnetic field.

This is still not quite enough. Charged particles will drift in a curved magnetic field, which causes them to leak out the outer side of the doughnut. We can solve this problem by making the magnetic field twist, like a French cruller. Particles near the outer edge, drifting outwards, will follow the magnetic field line around to the inner edge, where they will drift back towards the core.

The easiest way to make the magnetic field twist is to run a current through the plasma. You don’t need to (and can’t) run a wire there. Plasmas are full of charged particles that can move. When more of the electrons move in one direction around the doughnut then in the other direction, it will create a current.

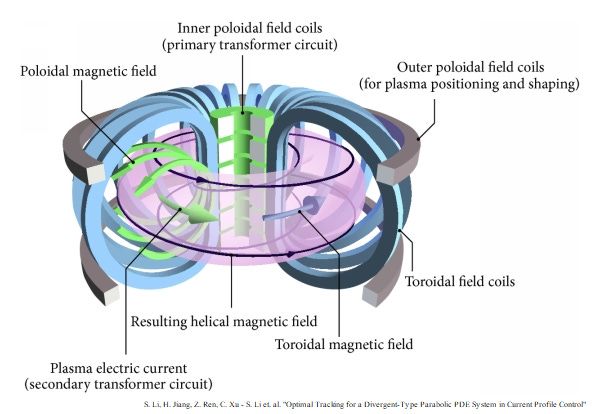

So a fusion experiment should (1) create an extremely strong magnetic field pointing around the doughnut, (2) heat deuterium and tritium to 100 million degrees inside the doughnut, and (3) drive a current around the doughnut.

The magnetic field can be created by superconducting electromagnetic coils which go around and through the doughnut. Turning on the coils provides some initial heating and current, but to sustain it, you need to inject accelerated particles or waves from the side.

This kind of fusion experiment is called a tokamak [10].

Figure 5: The coils and magnetic fields of a tokamak.

Figure 5: The coils and magnetic fields of a tokamak.

Small, Medium, and Large Experiments

I find it helpful to classify fusion experiments by their size. This is not standardized, so different people will classify them differently.

The larger the experiment, the farther the particles have to move (perpendicular to the magnetic field) to get from the core to the outer edge. Larger experiments inherently have a longer confinement time.

Small fusion experiments are sometimes called ‘tabletop’ experiments. This doesn’t always mean that they fit on a tabletop, but they can fit in the physics building of a research university without too much disruption. The doughnut has a radius of about 1 m. The support requirements (power supply, control systems, measuring equipment, etc.) aren’t too different from other physics labs.

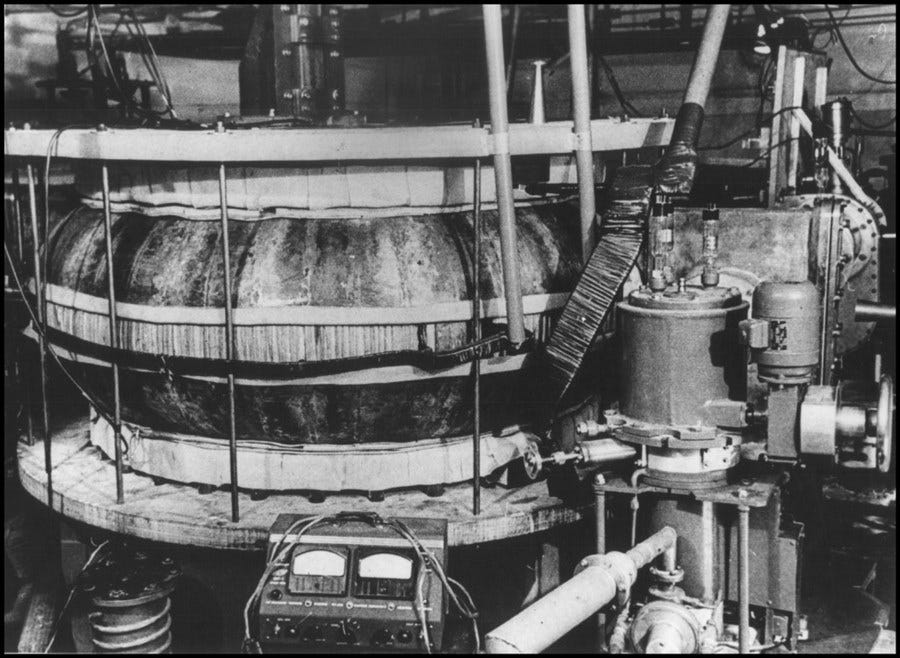

Figure 6: The first tokamak, T-1, did fit on a tabletop.

Figure 6: The first tokamak, T-1, did fit on a tabletop.

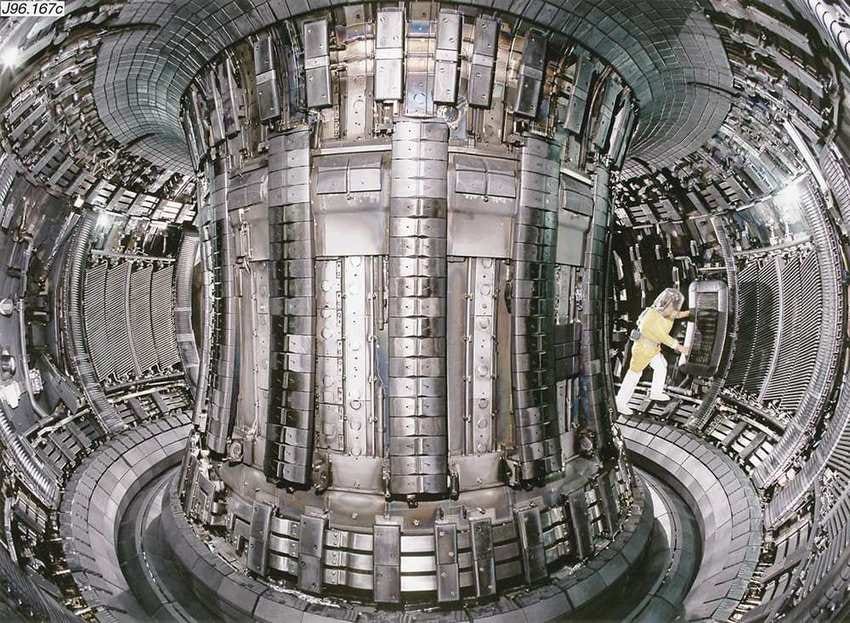

Medium fusion experiments have a radius of about 1.5 - 3 m. They require their own facility for all of their support systems, but they typically fit in a single building. One prominent medium experiment is JET [11].

Figure 7: Someone inside JET. They have to wear a protective suit because tritium is nasty stuff.

Figure 7: Someone inside JET. They have to wear a protective suit because tritium is nasty stuff.

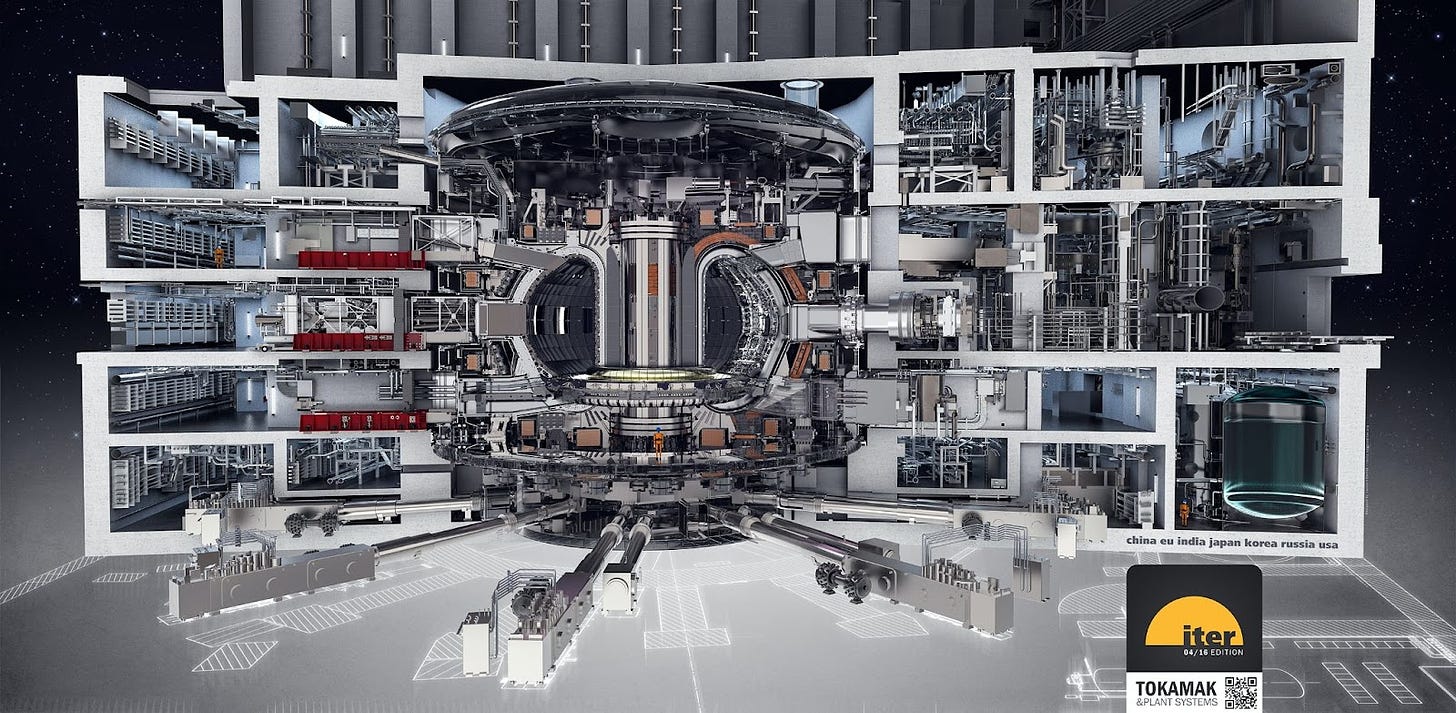

Large fusion experiment means ITER [12], an experiment currently under construction in southern France. ITER has a diameter of over 6 meters. The experiment itself has a five story building. Supporting buildings cover about 100 acres or 0.5 km2.

Figure 8: Construction at ITER as of May 2021.

Figure 8: Construction at ITER as of May 2021.

ITER

We can now answer some of our earlier questions. The reason why progress has stalled is because we did as much as we could do on medium experiments.

No country has been willing to provide enough money to build its own large experiment. So the fusion community has been gathering money from all around the world for decades for a single project [13]. ITER is supported by Europe (EU + UK + Switzerland), the US (which withdrew in 1999 and rejoined in 2003 [14]), Russia, Japan, China, South Korea, and India.

Figure 9: There are three people in this diagram. Can you find them?

Figure 9: There are three people in this diagram. Can you find them?

ITER is designed to get Q=10.

Despite getting 10 times as much energy from fusion as we put into the plasma, ITER is not designed to get engineering breakeven. ITER is designed as an experiment, not as a power plant. There will be tons of measuring devices pointed inwards. There are four different ways to heat the plasma and drive the current. This all allows you to learn more, but it requires extra power and lowers the overall plant efficiency.

ITER will be followed by a demonstration power plant, named DEMO [15]. A fully optimized power plant should be able to reach engineering breakeven as long as Q>5. This is why I chose Q=5 as my criterion for ‘getting fusion’.

ITER is also testing multiple designs for the tritium breeding blanket. Tritium is expensive and radioactive, so you want to produce it on site. The D-T fusion reaction produces a neutron, which we want to absorb, so we can use it to produce tritium. ‘Breeding’ is when we use a neutron to produce a more useful isotope. It is a ‘blanket’ because it surrounds the entire plasma, keeping the neutrons from going anywhere else.

The best reaction to produce tritium involves lithium-6:

36Li +01n 24He +13T .

This reaction also releases energy, which increases the power produced by about 25%. The tritium breeding blanket needs to make this reaction occur as much as possible, to efficiently carry the heat away so it can be used to generate electricity, and to provide a way to extract the tritium produced.

ITER is scheduled to begin their first experiments in 2025. Part of why I think that we are about to make rapid progress again is because we are finally getting a large experiment.

There have been problems with ITER staying on schedule and under budget. This isn’t surprising for a collaboration between governments representing over half the world’s population. In 2014, ITER got a new director, recalculated its expected cost, and underwent a major restructuring. Since then, ITER has largely stuck to this schedule and budget. Recently, there has been a 6 month delay because the French nuclear agency did what nuclear regulatory agencies do best, but this has been the longest delay since 2014.

It is still possible for ITER to fail. The biggest risk involves disruptions. Sometimes, the plasma in a tokamak becomes unstable and all of the plasma hits the wall at once. This could melt some extremely expensive equipment and take years to repair. If ITER cannot get disruptions under control, then it would be a failed experiment. This is especially challenging because pushing for higher Q makes disruptions more likely. ITER is planning on being extremely cautious: Experiments begin in 2025, but it won’t operate at full capacity until 2035.

ITER has been the focus of the fusion community now for decades. The Future of Fusion Energy similarly makes ITER the centerpiece of the book.

Things. Have. Changed.

ITER by itself is not enough to justify the high level of confidence I express at the start.

When Parisi & Ball finished writing this book in April 2018, ITER was basically the only game in town. Since then, Things. Have. Changed.

Historically, private fusion companies were almost entirely jokes or frauds. They make outlandish claims, use completely different designs so they can’t build on the progress of Figure 3, and they can be safely ignored. For example, Lockheed Martin [16] claims that it will take them five years to build a prototype of a fusion power plant that will fit in a truck. They have yet to publish evidence that they have produced a fully ionized plasma. Maybe they’re just being secretive, but their design has solid components in the plasma. That won’t work.

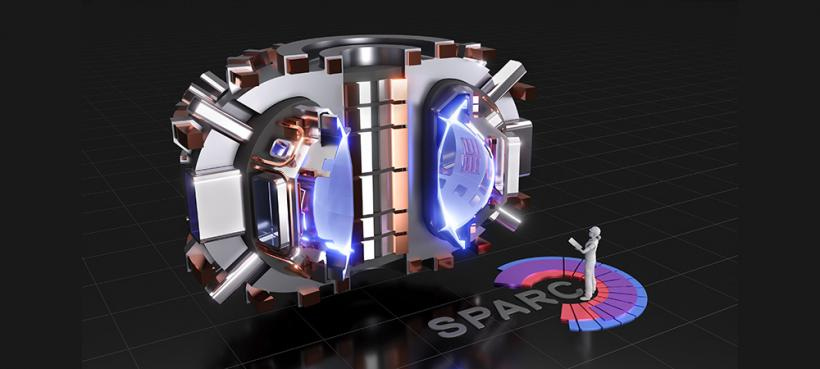

A new generation of private companies have surged into fusion. Leading the charge is Commonwealth Fusion Systems and their tokamak SPARC [17].

Recent advances in high temperature superconductors have been a game changer. They can produce a much stronger magnetic field which allows for better confinement in a smaller experiment. We should now be able to get Q=10 in a medium experiment, which costs ten times less than ITER [18] and is within the reach of private venture capital.

Figure 10: Finding the person here is much easier.

Figure 10: Finding the person here is much easier.

When the Department of Energy decided to close the third largest plasma experiment in the US, the MIT group which ran it found itself adrift. They founded Commonwealth Fusion Systems in 2018 with a goal of getting fusion within 10 years [19]. Since then, they have built the first ever high temperature superconducting coil in 2019, released their engineering plans for SPARC in 2020, began construction in 2021, and plan on finishing construction in 2025.

Commonwealth Fusion had just been founded when Parisi & Ball wrote in 2018. Now they’re leading the race to fusion.

Several other startups are following SPARC’s strategy of using stronger magnetic fields to get fusion in a smaller experiment. They use a variety of designs.

Alternative Designs

To understand how the alternative designs are different, we need to make sure we understand the basic strategy for getting fusion in a tokamak. Let’s run through it again:

(A)

We want to get lots of fusion reactions …

… so we want a large triple product (density * temperature * confinement time).

(B)

The fusion plasma is too hot to touch solid objects …

… so we put it in a magnetic bottle shaped like a doughnut.

(C)

The particles drift outwards, leaving the bottle …

… so we twist the magnetic field with a current in the plasma.

I will start with the alternatives that are most similar to a tokamak. For each one, I will list the best experiments that currently exist, where they’re located, and the year they began operation.

Tokamaks have been better researched than any other strategy. There are currently 10 medium tokamaks:

-

T-10 (Russia, 1975)

-

ASDEX (Germany, 1980)

-

JET (England, 1983)

-

JT-60 (Japan, 1985)

-

DIII-D (USA, 1986)

-

HL-2A (China, 2002)

-

EAST (China, 2006)

-

KSTAR (Korea, 2008)

-

WEST (France, 2016)

-

HL-2M (China, 2020)

Plasma Shaping & Spherical Tokamaks

All magnetically confined plasmas have the basic shape of a doughnut. But if you cut the doughnut in half and look at it end on, the cross sectional shape can be different.

Early tokamaks had circular cross sections. JET was built with a cross section shaped like a ‘D’: wider near the inner wall and narrower near the outer wall. This was done for structural reasons, but it also improved the performance of the plasma. Most tokamaks since then have had this shape.

Spherical tokamaks have a taller height and smaller diameter than other tokamaks. They look more like a cored apple than like a doughnut.

The main benefit of a spherical tokamak is that you can get a larger plasma density with a smaller magnetic field. The main drawback is that there is less room in the central column for everything that needs to go there.

The best spherical tokamaks today are small, if you measure based on the radius, but medium if you measure based on the height. They are:

-

NSTX (USA, 1999)

-

MAST (England, 2000)

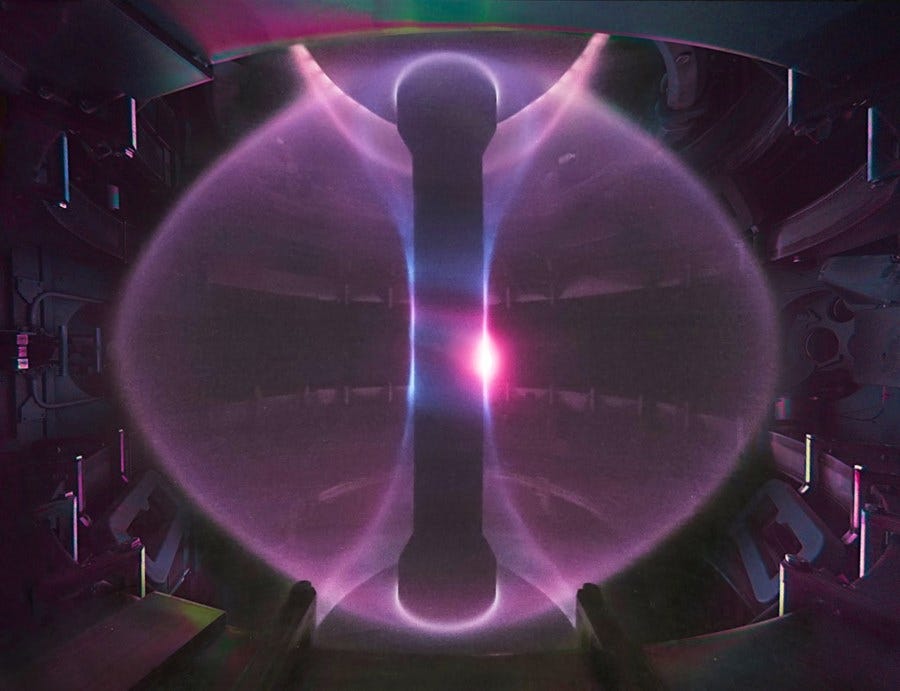

Figure 11: A picture of the plasma inside MAST.

Figure 11: A picture of the plasma inside MAST.

We haven’t explored other shapes very much. There might be one that works even better. There is currently a small experiment designed to look at as many shapes as possible:

- TCV (Switzerland, 2002)

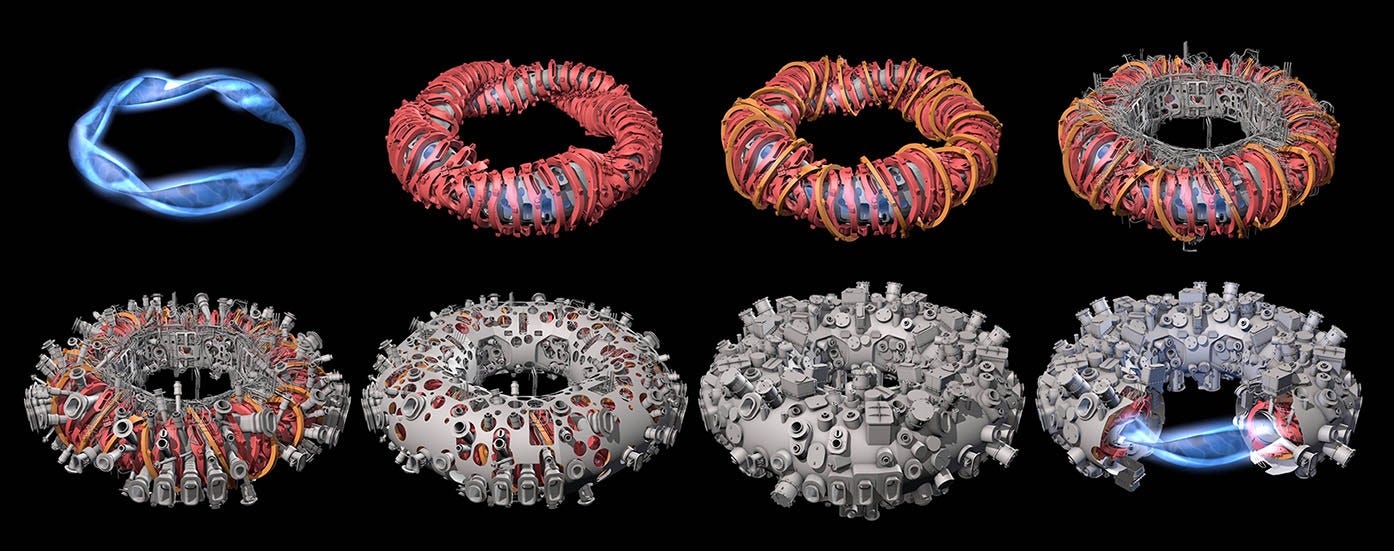

Stellarators

Stellarators differ from tokamaks at point (C). To twist the magnetic field, they use twisty coils outside the plasma instead of having a current in the plasma.

The main benefit of stellarators is that they don’t have disruptions. Disruptions are caused by the current in the plasma. If the plasma is already moving coherently, when things become unstable, that motion can be redirected into the wall. The plasma in a stellarator doesn’t have a current and isn’t moving. When it becomes unstable, it leaks heat slightly faster than normal until it cools down again.

Stellarators also have the best name, look the coolest, and are my favorite.

Figure 13: The layers of Wendelstein 7-X.

Figure 13: The layers of Wendelstein 7-X.

The main drawback is that stellarators are harder to design and build. There are lots of ways for coils to be weird and twisty and you want to find the best one. You then have to manufacture complex 3D shapes with high precision. This makes them more expensive than similarly sized tokamaks.

There are currently four medium stellarators:

-

TJ-II (Spain, 1997)

-

LHD (Japan, 1998)

-

Uragan-2 (Ukraine, 2006)

-

Wendelstein 7-X (Germany, 2015)

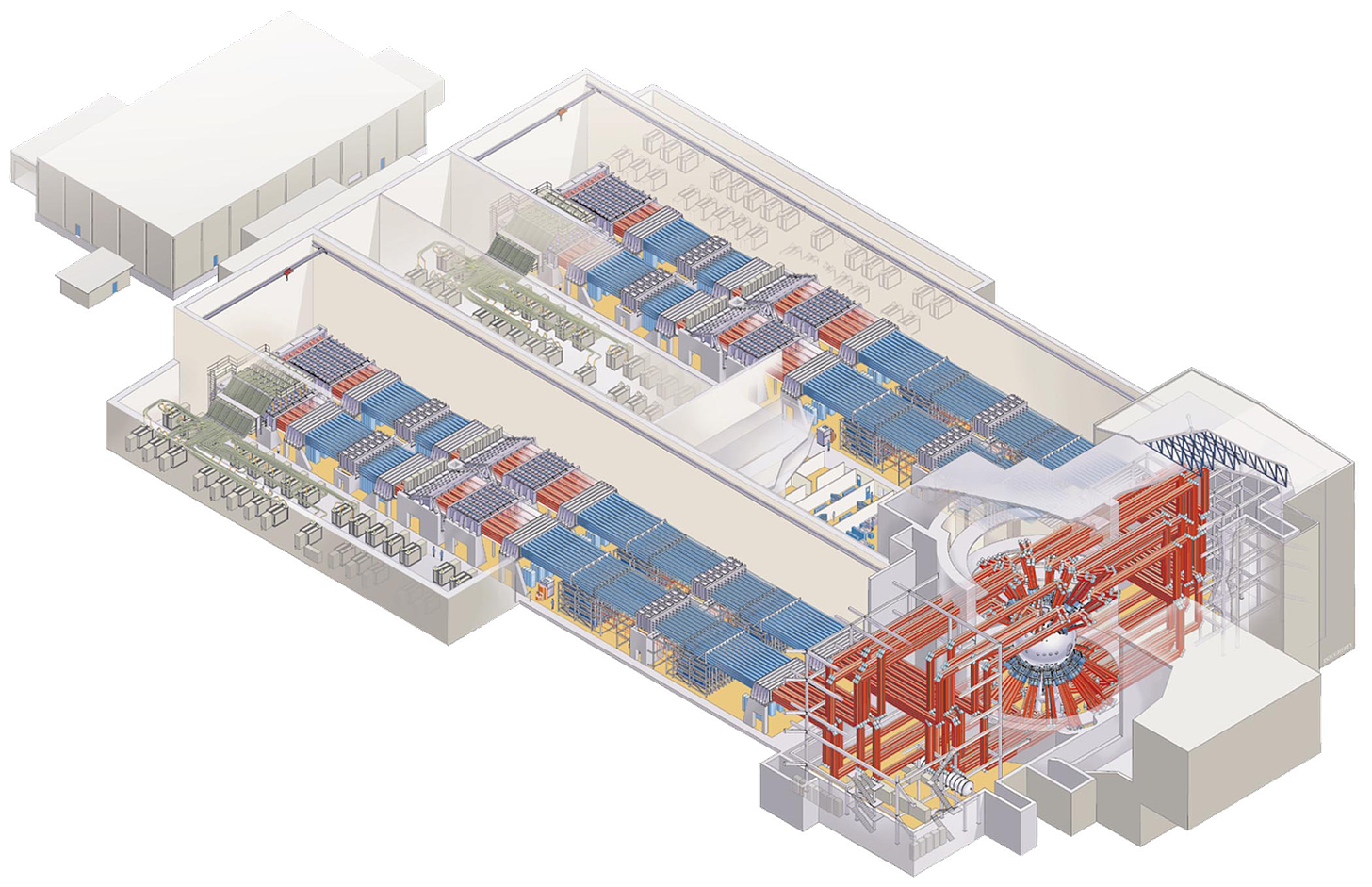

Inertial Confinement Fusion

This is a completely different strategy to get fusion, going all the way back to point (A). So far, to increase the triple product, we have mostly been increasing the confinement time. Unlike Magnetic Confinement Fusion, Inertial Confinement Fusion accepts a short confinement time and instead tries to increase the density.

Start with a small pellet [20] which contains deuterium and tritium. Shine lots of lasers on it from all directions. For a moment, the pellet receives 1,000 times as much power as the entire US and implodes. The deuterium and tritium briefly become hot and dense enough to get fusion, before expanding again.

Figure 14: The building layout for an inertial confinement experiment. The blue/red lines are the paths that the lasers follow before they enter the vacuum chamber (silver sphere on the right) where the pellet is located.

Figure 14: The building layout for an inertial confinement experiment. The blue/red lines are the paths that the lasers follow before they enter the vacuum chamber (silver sphere on the right) where the pellet is located.

Inertial confinement fusion experiments can also be used for [CLASSIFIED], so they get significant funding. Progress has been extremely rapid. They crossed Q=1 a few months ago.

There are still some major challenges. While magnetic confinement fusion can be done in a steady state, this has to be done in distinct ‘shots’. Currently, they can do about 1 shot/day. To make a power plant, you would need to do about 1 shot/second. I chose to include 1 shot/second as part of my criterion for ‘getting fusion’ if the experiment is not in a steady state.

The best inertial confinement fusion experiment is at the boundary between medium and large, although those categories were designed for doughnut-shaped plasmas, not for banks of lasers:

- NIF (USA, 2009)

Players and Predictions

Now that we have the strategies laid out, I will go through the groups that I think have a plausible path to fusion and make predictions for each one. I am only focusing on groups relevant for my headline prediction: Q>5 in steady state or with a shot frequency of 1/second before 2035 (80%) or 2040 (90%). I will also resolve this question to YES if anyone sells fusion power commercially, even if they don’t meet my technical requirements.

Government Tokamaks

ITER

ITER is still the biggest player in the field. They have the most money and the most people working to make it succeed. ITER moves slowly, but resolutely.

- ITER gets fusion by 2035 (50%) or 2040 (70%).

K-DEMO

Most of the countries in ITER plan on making their own large demonstration power plant, after they see if ITER succeeds. South Korea is being more aggressive and will build their DEMO while ITER is still doing its early experiments. The construction should be complete by 2037. Success here is highly correlated with ITER’s success.

- K-DEMO gets fusion by 2040 (70%).

CFETR

China seems to be willing to spend more money on fusion than most other countries: 3 out of 5 new medium tokamaks since 2000 have been in China. They’re planning on building a large tokamak like ITER in the 2030s and converting it into a DEMO in the 2040s. They don’t have detailed plans yet, but they might have reliable funding.

- CFETR gets fusion by 2040 (60%).

STEP

The United Kingdom has announced that it will not take part in Europe’s EU-DEMO, planned for the 2040s. Instead, they will build a large spherical tokamak by 2040. I’m not convinced that this will happen, but it would be great if it does.

- STEP gets fusion by 2040 (20%).

Private Companies

Commonwealth Fusion Systems / SPARC

I’ve already told their story because they are the current leader. Everything has gone well so far.

- SPARC gets fusion by 2025 (30%) or 2030 (70%).

Renaissance Fusion

Renaissance Fusion was founded in Grenoble, France in 2019. They are planning on building a stellarator that can get fusion by 2032. I can’t tell you their cool ideas for manufacturing the coils because they still haven’t published them yet. [21]

- Renaissance gets fusion by 2035 (50%) or 2040 (70%).

Type One Energy

Type One Energy was founded in Wisconsin in 2020. They are planning on building a stellarator using Commonwealth Fusion’s high temperature superconductors and 3D printing the steel supports for the coils. Their goal is fusion by 2031.

- Type One gets fusion by 2035 (50%) or 2040 (70%).

Tokamak Energy, Ltd.

This is a slightly older company, founded in England in 2009. They originally managed a spherical tokamak experiment [22]. More recently, they decided to try to get fusion by 2030 using a medium experiment and high temperature superconductors. Spherical tokamaks are less well tested at this size and don’t benefit as much from having a stronger magnetic field.

- Tokamak Energy gets fusion by 2030 (10%) or 2035 (30%).

Marvel Fusion

Marvel Fusion was founded in Germany in 2019. They’re working on inertial confinement fusion, which I have much less expertise in. Inertial confinement fusion has made rapid progress recently and they have recruited some good people, so they should have a chance. Some problems include not releasing a timeline and not planning on using D-T fuel.

- Marvel gets fusion by 2035 (30%).

Honorable Mention: Helion

Helion is the most serious of the previous generation of fusion startups that I dismissed above. They are using an entirely different strategy from the rest of the fusion community. It is closer to Magnetic Confinement Fusion, but it does occur in discrete shots. There isn’t anything obviously wrong with it, but they can’t build on the progress of Figure 3.

Instead, they’re working on their own experimental program. They’re on their 6th prototype, Trenta. It is a small experiment which can do 1 shot every 10 minutes. Their next experiment, Polaris, should be a medium experiment which can do 1 shot/second. They claim that it will get fusion by 2024.

One good thing about Helion is that they have a more efficient way of directly converting the energy in the plasma into electricity. One bad thing is that they claim to be using helium-3 as a fuel. This is harder than D-T fusion [23] and it doesn’t fully represent what they’re planning. Their entire fuel cycle involves 50% D-D fusion, 25% D-T fusion, and 25% D-He3 fusion.

Helion is also notable because they’ve gotten more private funding than any company other than Commonwealth Fusion Systems.

I’m more skeptical. At least it seems unlikely that they will get fusion on their first medium experiment, especially since that requires improvements of multiple orders of magnitude in both triple product and shot frequency. They should expect to design an 8th experiment based on what they learn from Polaris.

- Helion gets fusion by 2025 (5%) or 2030 (20%).

Summary

I hope that it is striking how many and how different the plausible paths to fusion are. From a physical standpoint, we have tokamaks, stellarators, spherical tokamaks, and inertial confinement. From an engineering standpoint, there are different superconductors for the coils, different manufacturing techniques, and more. From an institutional standpoint, we have public and private enterprises in seven different countries.

In 2018, there was a single failure point: if ITER failed, it would delay fusion by decades. Now we can afford some failures. Because the players are so diverse, the failures are unlikely to all be correlated.

Fusion is still hard. I am not predicting that any path to fusion has more than a 70% chance of success. But we only need one to succeed. Taken together, we can be confident that we will get fusion soon.

I’m reminded of my thoughts on covid vaccines back in Spring 2020. There were lots of candidates, which were extremely different both biologically and institutionally. I don’t know enough about vaccines to determine how likely any one was to succeed, but I took comfort in knowing that there were a lot of options. We only needed one to work well, and we ended up getting multiple.

It is still possible for us not to get fusion by 2040. Maybe we never figure out how to deal with disruptions in tokamaks and all of the private companies fail. But it is also possible for multiple paths to succeed. ITER could end up being fifth to fusion. [24]

Conclusion

If you want to learn more about fusion, I highly recommend The Future of Fusion Energy.

It discusses the fundamentals of fusion, plasma confinement, ITER, and the design of a fusion power plant in much more detail than I could here. Several topics that are tangentially related, such as other energy sources and nuclear proliferation, have overviews that I hope become common knowledge. There are also more specialized topics, like the history of fusion, what questions to ask a fusion startup to tell if it’s legitimate, and why fusion is the only power we could use for interstellar travel that is currently theoretically possible. The final 3 pages are joke recipes for doughnuts, based on different strategies for getting fusion.

The only things missing are the surprising new developments in private fusion that have occurred since the book was published. These new, diverse paths have made me much more confident that we will get fusion soon. When ITER was the only game in town, I predicted only a 50% chance of getting fusion by 2035 and a 70% chance by 2040. Now, those numbers are 80% and 90%, and we could get fusion a full decade sooner.

It is time to start getting excited about fusion !

Endnotes

[1]: By ‘get fusion’, I mean Q > 5 for a steady state experiment. If it is not steady state (e.g. inertial confinement fusion), then I also require a shot frequency of at least 1/second. Anyone selling fusion power to the grid also counts, even if they don’t meet these technical requirements.

[2]: My dad is a doctor, so that should give you some idea at how bad he is at math.

[3]: The fusion reaction chain in the sun burns six protons (hydrogen nuclei) into helium-4, two protons, and two positrons over the course of five fusion reactions. What we do is simpler.

[4]: The number of protons + neutrons is the mass of the atom in amu, while the number of protons is the charge of the atomic nucleus in units of e. The mass and charge can be measured directly, so we write them instead of the number of protons and the number of neutrons.

[5]: This is an order of magnitude estimate. Fire occurs at a few hundred or a few thousand degrees Kelvin (or Celsius or Fahrenheit).

[6]: In particular, the confinement time for the energy. The particles are always at least as well confined as the energy. When the particles leave, they take energy with them. Energy can also leave through light or various plasma waves.

[7]: There is also ‘engineering breakeven’, when you get more energy out of the entire power plant than you put in, and ‘economic breakeven’, when you get more money out of the entire power plant than you put in. We need to get scientific breakeven first.

[8]: This was named after blood plasma by Langmuir in 1928. He thought the electrons and ions moving in the plasma were like red and white blood cells moving in blood plasma. Everyone else thinks that the analogy is rather stretched.

[9]: The mathematical proof that this shape must be a doughnut and cannot be anything like a sphere is called the Hairy Ball Theorem. Justin Ball modeled it with the top of his head.

[10]: ‘Tokamak’ is a Russian acronym for тороидальная камера с магнитными катушками, which means ‘toroidal chamber with magnetic coils’.

[11]: JET is an acronym for Joint European Torus. It is located in England as a thank you for British special forces helping to rescue a German plane being held hostage by terrorists in 1977. More recently, JET itself was held hostage as part of the Brexit negotiations.

[12]: ITER used to be an acronym for International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. We decided we didn’t like that branding, so now it is Latin for ‘the way’.

[13]: The fusion community has a long tradition of internationalism. We refused to take part in the Cold War and have collaborated across the Iron Curtain since 1958. I do wonder if we could have gotten more funding if we were trying to Beat the Russians instead of working with them.

[14]: This isn’t part of the official justification, but the US rejoined ITER to help convince Britain to join the Iraq War. Fusion projects are often used as prestige chips in international negotiations.

[15]: DEMO never was an acronym, but we still write it like one.

[16]: I don’t want to do too much criticism of people aiming for Progress, even if I don’t think they will be successful. At least criticizing Lockheed Martin is punching up.

[17]: SPARC is a nested acronym for Smallest Possible ARC. ARC is an acronym for Affordable, Robust, Compact and is an Iron Man reference.

[18]: Commonwealth has raised $2 billion so far, compared with ITER’s price tag of $45 billion.

[19]: This is a rare example when government cuts to research funding drives technological progress. These particular cuts ended up being reversed and Alcator C-Mod is still operating.

[20]: About 1 mm in diameter.

[21]: I know this because I might have gotten a job with them, but it didn’t work out. I am not currently working for any of these groups.

[22]: The largest tokamak currently operating in the US, DIII-D, is also managed by a private company, General Atomics, which gets most of its funding from the Department of Energy.

[23]: D-He3 fusion requires a triple product about ten times larger than what is needed for D-T fusion, including about a five times higher temperature. D-D fusion works best at the same temperature as D-T fusion, but requires a triple product about fifty times larger.

[24]: After SPARC, Type One Energy, Renaissance Fusion, and one of Tokamak Energy, Marvel, or Helion.