Your Book Review: The Weirdest People in the World

[This is one of the finalists in the 2023 book review contest, written by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done. I’ll be posting about one of these a week for several months. When you’ve read them all, I’ll ask you to vote for a favorite, so remember which ones you liked]

Down from the gardens of Asia descending radiating,

Adam and Eve appear…— Walt Whitman

When I grew up I was still part of a primitive culture, in the following sense: my elders told me the story of how our people came to be. It started with the Greeks: Pericles the statesman, Plato the first philosopher, Herodotus the first historian, the first playwrights, and before them all Homer, the blind first poet. Before Greece, something called prehistory stretched back. There were Iron and Bronze Ages, and before that the Stone Age. These were shadowy, mysterious realms. Then history went on to Europe. I learnt as little outside Europe as I did before Greece. There was one class on 20th century China, but that too was about China becoming modern, which meant European.

A big silent intellectual change of the past quarter century is the broadening of our self-concept. Educated Westerners are starting to expect each other to know Chinese and Islamic history, which are still ongoing, and perhaps something about pre-Columbian America whose stories were traumatically ended by the conquest of the New World. The earlier past is moving into the light, too. Ancient states like Babylon and Egypt are gradually coming alive: Hammurabi and Gilgamesh get more play relative to Solon and Achilles. And before that, the real prehistory of the first cities, the Neolithic, the growth of agriculture, the end of the Ice Age at 10,000 BC, modern humans around 100,000 BC, the first humans at 1mya (million years ago)… these dates are gradually getting fixed in the mind as turning points in the story of us.

The difference between Greece and Rome on the one hand, and Babylon and Egypt on the other, was that Greeks and Romans had written down their stories for us. Their stories had become our story. History was a narrative. Each of its chapters had a beginning, middle and end. How else would you tell it? Now, as we go farther back, we have less and less writing to rely on. Even when we have writing, on papyrus or stone, it isn’t self-interpreting – it’s not history the way Herodotus and Livy tell us history, with the explicit goal of recounting the past. Earlier still the texts die out completely, and we are left with stones and bones. Our knowledge of this history has to come from science: from archeology, anthropology (in the hope of using present societies to learn about past societies), and now also the new science of historical population genetics. Joe Henrich has done more than most to teach us our history using these tools. His marvelous book The Secret of Our Success told the human narrative from the point of view of the unique human capacity for cumulative culture1.

The question was always going to arise: how do we fit the big story of humanity, told by modern social science, together with the story of Europe told by narrative history? Henrich’s latest book, The Weirdest People in the World , goes there2.

The big question

Coming as he does from the scientific side of the aisle, Henrich isn’t just going to tell a story. He has a hypothesis about an empirical puzzle. The puzzle is the most important question, the big one, the one that once you think about it’s hard to think about anything else, the economists’ Holy Grail since Adam Smith: why are some countries rich and others poor?

His hypothesis comes from cross-cultural psychology. The West got rich because Westerners are different. People from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic societies are WEIRD – the acronym comes from a previous article of his. In particular, compared to everyone else in the world and in history, modern Westerners:

-

Are individualist, not collectivist or conformist

-

Feel more guilt and less shame

-

Explain people’s actions by their innate dispositions, not their social role

-

Reason analytically not holistically

-

Follow more universal norms and less relationship-specific norms

-

Are more patient

-

Trust strangers more and are more honest.

This psychology might make societies richer, for fairly well-known and plausible reasons. The Weirdest People in the World (henceforth just WEIRD) sets out a causal chain from cultural change to psychological change to modern economic growth. The start of that chain is surprising: an obscure set of rules pushed by the medieval Catholic church, which banned marriage between cousins. The most important argument of the book is that these rules created WEIRD psychology.

How it worked: these marriage regulations served to dismantle intensive kin networks, which are the social cement of society almost everywhere else in the world. For most people in history, family hasn’t just been the place where children grow up and couples spend time together. Family has been the basic human group, and there have been extensive and precise rules dictating who counts as family (or clan) and how each person should act with respect to different relatives. The Church’s regulations, the Marriage and Family Programme (MFP), aimed to replace intensive kinship, and over many centuries it was more or less successful in doing that. We’ll come back shortly to why it wanted to.

So, the causal chain looks like this3:

WEIRD ‘s key evidence is the link between the places where the Church promulgated the MFP and a set of psychological and social outcomes: the level of cousin marriage, the psychology of people living in those places today, social capital and economic growth. This is the scientific story of European history, and Henrich’s answer to the most important question in the world.

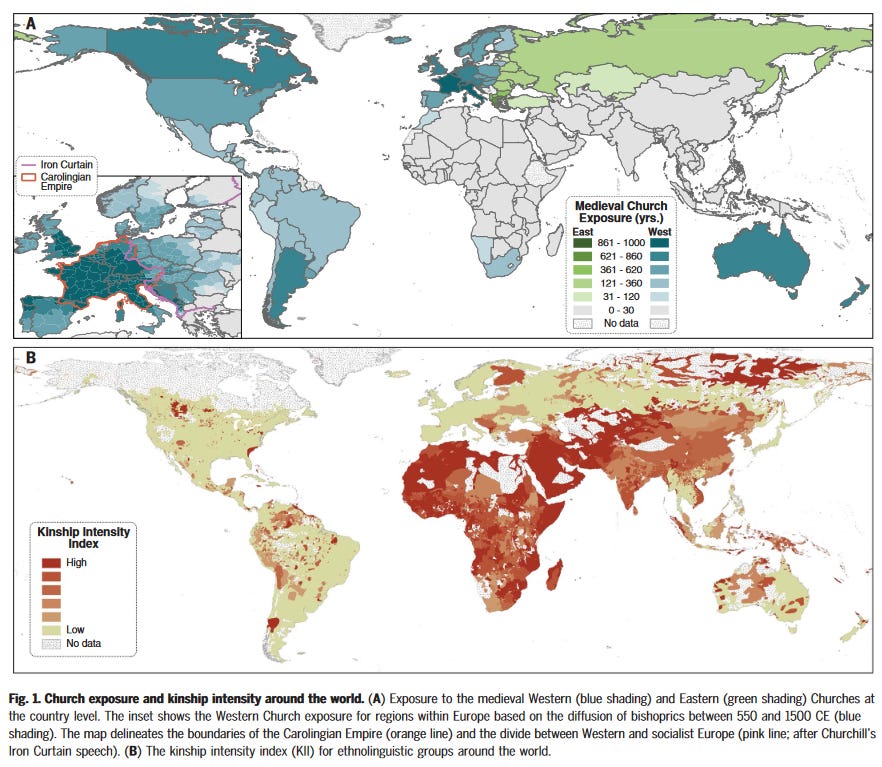

These maps fromone of the scientific articles behind WEIRD show the basic causal claim: the medieval church reduced the intensity of kinship institutions.

These maps fromone of the scientific articles behind WEIRD show the basic causal claim: the medieval church reduced the intensity of kinship institutions.

He tells it with an extraordinary mastery of a very wide range of sources from anthropology, psychology, behavioural economics, economic history, and historical narrative. This book is for everyone, but the connoisseur will enjoy the bibliography: if you think it’s important and relevant, it’s probably in there, and there was also plenty of work which I did not know, and now feel I should. It takes a very smart person to keep this many balls in the air. Being at Harvard probably doesn’t hurt either – that’s the “collective brain” of the human network, which makes an appearance later on in the book.

So this book really sets down a marker: the anthropologists are returning from the Amazon, the Sudan and Polynesia, and coming for Western history and economics. It will be interesting to see how those target disciplines react.

Is it true?

Economists and historians think about Western history very differently.

Historians love irony and contingency. They enjoy byways. Triumphalist, linear narratives of progress are distrusted as “Whig history”. Growth economists, by contrast, are all about the linear bigness. They have a relentless focus on the one question of how the West got rich, and if you call that triumphalist, they will take out a chart of South Sudanese child mortality and laugh at you.

Both historians and historical economists — a more appropriate name than “economic historians” nowadays — are interested in causality. But economists have a crunchier, more “scientific” standard for what counts as proof of causality. You’ve got to have a treatment and a control group, and by default if you claim there are no confounds, they won’t believe you. You need you some plausible exogeneity. A random river where Napoleon’s armies stopped. The distance from Wittemberg where Luther nailed up his theses. And then, how does that affect something that matters today (if it doesn’t, then who cares?) Of course, the longer ago the exogenous treatment, the more impressive the result.

You can see the incentives that these disciplinary demands might set up, and that might worry you. At worst, you might get a kind of “underground river” concept of history, where

-

X happened long ago

-

[underpants gnomes whispering]

-

Y is correlated with X today

Indeed this does seem to skip all the interesting, contingent bits:

On the other hand, if you want to explain an all-important outcome like the take-off into modern economic growth, then you can’t just mumble “one damn thing after another” or “irony and contingency”. That a hundred things randomly conspired to make the West Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic is not a satisfying story. Why would the die rolls keep favouring this one place? (And you can’t invoke the law of large numbers. There are only five continents in the world, and modern economic growth did not have to happen anywhere at all.)

To get from Europe 1 AD to modernity, while paying reasonable attention to the many accidents along the way, there are really only two possible narrative genres.

The first is the rock falling down a mountain. It starts with one big, random event. This then triggers other events, and they trigger others, and now you have an unstoppable landslide. But the chance is at the start.

The second is the cyclist pushing his bike up a mountain. It takes an actor who deliberately over time overcomes one obstacle and dodges another, until eventually they get to the top, and from there it’s a downhill ride.

WEIRD belongs firmly in the landslide genre. The big event is the Marriage and Family Program of the Western Church. This sets off a landslide, which the later chapters detail: the decline of kin institutions, the rise of Italian communes and city-states in the middle ages, the idea of individual rights in the European law merchant, the development of Protestantism, and finally the trifecta of science, commerce and democracy. WEIRD psychology is there, as an unobserved helper, for each stage of this journey, but each stage also builds on the previous ones.

It’s not by chance that WEIRD tells the West’s story as a landslide. First, this is part of cultural evolution’s baggage of intellectual commitments. Homo culturalis doesn’t figure out solutions to his problems by abstract thought; he’s not a natural optimizer. Instead he feels his way towards solutions. In a now famous example from The Secret Of Our Success , nobody just sat down and worked out how to detoxify manioc. Cultures which did this job better just had an evolutionary advantage.

Second, the “bicycle push uphill” story would threaten the clean causality of the natural experiment. Suppose the Western Church promulgated the MFP with the deliberate plan of creating WEIRD psychology and causing the take-off into modern economic growth. Okay, that’s unlikely, but suppose it promulgated the MFP with a plan that was somewhat related to increasing human welfare (in this world, not the next). Then we might suspect two things:

- Maybe in doing so the Church was reacting to existing conditions: reading the human situation and responding “hey, what we need here is less intensive kinship”.

If so, then it might put more effort into pushing the MFP in places where that was likely to have higher payoffs: in, say, the centre of the Carolingian empire – the strip running north-south roughly from Belgium to North Italy, where many trade routes meet, and which will be the richest part of Europe from at least the 12th century until the 21st. Not so much in Ireland, at the edge of the known world, long on monks but low on opportunities for trade; or in Sweden where the Church has barely a foothold. But now that threatens the randomness of your treatment, because the MFP correlates with existing economic institutions.

- Also, maybe when and where it did the MFP, the Church also took other actions to achieve the same goal.

That goal being not modern economic growth, but perhaps that “the earth shall be filled with the glory of God, as the waters cover the sea”. Again, if so, there goes randomness, because the MFP correlates with those other actions.

What was the Church’s plan? The book deals a bit briefly with that. It insists, surely correctly, that the Church was not aiming to create modernity or grow the economy. On the other hand, it doesn’t claim that the Church was just flailing around at random: “Ultimately, the Western Church, like other religions, adopted its constellation of marriage-related beliefs and practices – the MFP – for a complex set of historical reasons… By undermining Europe’s kin-based institutions, the Church’s MFP was both taking out its main rival for people’s loyalty and creating a revenue stream.” Elsewhere, Henrich insists that the effects of the MFP were causally opaque to the Church, and more generally, that most institutions of modernity – like human institutions in general – were created not by reason and forethought, but as unintended outcomes of people who didn’t really know what they were doing.

Hmm. Here is what John Bossy says, in his short but brilliant book Christianity in the West 1400-1700 , on marriage:

[The Church’s view on marriage] was accepted, because people recognised it as godly on grounds which had been stated by St Augustine a millennium before. These were that the law of charity obliged Christians to seek in marriage an alliance with those to whom the natural ties of consanguinity did not bind them, so that the bonds of relationship and affection might be extended through the community of Christians…. The form in which the doctrine was normally now held was that marriage alliance was the pre-eminent method of bringing peace and reconciliation to the feuds of families and parties, the wars of princes, and the lawsuits of peasants.

And on death:

In outline the rites of death were practically anti-social… they dealt with a soul radically separated, by death-bed confession and last will, from earthly concerns and relations…. Radical individualism… was embodied in the liturgy of death. It was expressed in its most memorable invocations… “Libera me domine de morte aeterna…”… And this entailed something more than the evident fact that we die alone: it had to do with the doctrine… that the destiny of the soul was settled not at the universal Last Judgement of the Dies Irae, but at a particular judgement intervening immediately after death. More mundanely, it had to do with the invention of the will, liberating the individual from the constraints of kinship in the disposition of his soul, body and goods, to the advantage, by and large, of the clergy.

So, the Church’s ideology may not have been accepted blindly: people were aware of the social consequences. And on the other hand, the Church’s programme is not simply an institutional change that then happens to alter human psychology. Part of what it does is directly and deliberately move human psychology towards individualism! You are alone before God’s judgement.

The distinction between intended and unintended is not always clearcut. People in the Church thought extremely seriously about the world, though with a very different orientation from a modern development economist. They also had incentives to raise economic output: as the recipient of bequests, and later as the largest landholder in Europe, they were in the position of Mançur Olson’s famous “stationary bandit”, standing to gain a share of any proceeds from faster growth.

Utopias

In the beginning was Reason.

John 1.1

I am very positive about the broad programme of integrating anthropology with history, but I think that one aspect of Western thought is a bit different, maybe even “unique”, from a very early point. That aspect is the idea that we can rethink society rationally from the ground up. It starts in Book II of Plato’s Republic , when Socrates says that the city-state is the reflection of the individual and vice versa , and that you can’t understand the good for an individual person without working out what the ideal city would look like. And in the rest of the book, he goes on to reorganize society – in his and his interlocutors’ minds – by reason alone. Property in common! Men and women brought up the same! Disabled children, uh, left out to die! Some of these ideas, good and bad, get put into practice twenty-five centuries later.

As far as I know, this deliberate project of blank-slate rational institutional design, also known as political philosophy, is unique to Western thought, but I’m happy for an expert on Confucius or Ibn Khaldun to correct me. In any case, it seems relevant, because shortly after the fall of Rome in 410 AD, Saint Augustine wrote the most famous work of Christian political philosophy, the City of God , and this is one of the first places where the ban on cousin marriage is discussed:

“For affection is now given its proper place, so that men, for whom it is beneficial to live together in honourable concord, may be joined to one another by the bonds of diverse relationships: not that one man should combine many relationships in his sole person, but that those relationships should be distributed among individuals, and should thereby bind social life more effectively by involving a greater number of persons in them….

To the patriarchs of antiquity, it was a matter of religious duty to ensure that the bonds of kinship should not gradually become so weakened by the succession of the generations that they ceased to be bonds of kinship at all. And so they sought to reinforce such bonds by means of the marriage tie…. Thus, when the world was now full of people, although they did not like to marry sisters… they nonetheless liked to take wives from within their own family. Who would doubt, however, that the state of things at the present time is more virtuous, now that marriage between cousins is prohibited? And this is not only because of the multiplication of kinship bonds just discussed [i.e., it is partly because of that]…. ”

City of God Book XV Ch. 15, trans. R. W. Dyson

So, Augustine does understand that marriages within the family “bind social life” less effectively than marriages across families, and that banning cousin marriage helps that. And he has a normative reason why the Church should care: it’s good for men “to live together in honourable concord”.

The idea that people are just feeling their way and long-run outcomes are unintended is a deep methodological commitment of cultural evolution. It’s built into the models4. But you need to be careful in applying that universally, because one part of human progress is the scaling of human forethought, from this season’s harvest and our small group, to the far future and the whole planet. That is how, in the early 21st century, humanity can be trying to rejig the entire world economy so as to avoid the future peril of global warming. And blindness/forethought is a continuous variable, not a dichotomy. The Western Church had some degree of collective agency, just as Google or the US does today, and it understood what it was doing under some description.

It is worth thinking how a historian might tell the story of “the West getting prosperous” in the bicycling-up-a-mountain genre. One response is that narrative just isn’t good enough to prove causality. A bunch of bloody stories aren’t a substitute for real science! But that seems too negative. In court, the facts of a case are established by narrative: you can’t run a randomized trial to decide whether Colonel Mustard did it in the pantry with the candlestick. I think at best, historical narrative can establish causality the same way. In doing so it leans on existing human knowledge. The Western Empire ultimately collapsed because the Vandals took North Africa. We think so because of simple physical facts: how much grain a human needs to survive, the Empire’s population, the agricultural capacity of Europe with Africa cut off. Other historical claims are based on common sense psychology. The First Crusade doesn’t happen without Urban II’s speech to the assembled French nobility at Clermont, because no sensible knight would set off to fight the Saracens on his own.

So you might simply ask what were the incentives and ideas of the Church over the medieval period – and the choices and ideas of the people who listened to the Church, because acceptance is never passive – and tell the story of how this played out.

The big push

Here is one difference between a bicycle push and a landslide: once started, landslides always keep going. The Church no longer holds sway over Europe, but Henrich (I think!) believes that the change to WEIRD psychology is irrevocable. Extended kinship is dead. New institutions have arisen to take its place: fraternities and monasteries and communes, and the Law Merchant, in the Middle Ages; and then Reformed Christianity with every man a priest, then science and democracy. The bicycle push uphill is different. If you stop pushing, you might stop moving.

Here’s one thing that looks to me like a historically extended push: from the earliest Reformers onwards, the constant drive towards character education. It starts with Lutherans trying and failing to reform the country peasants by teaching them their catechism5. Then the later Puritans and Pietists, copying back from Counter-Reformation spirituality, going deeper into themselves before they try to change the world; the first children’s books, the great spiritual classics like Pilgrim’s Progress. Then the secular 18th century experimenters like Rousseau; and the first state education systems – all universally agreed that the point of education is character, not technical skills; and mostly within a broadly Christian framework.

If you think that contemporary education looks pretty different, and that the other teaching institutions Westerners built to support their norms have also changed, then what would you predict will happen?

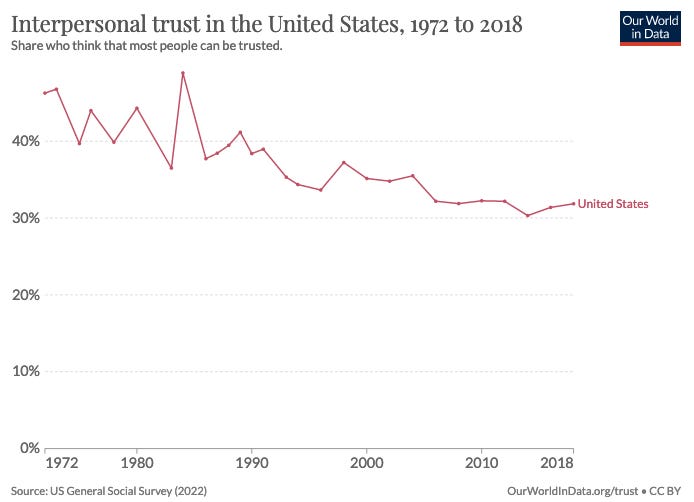

Two quick graphs:

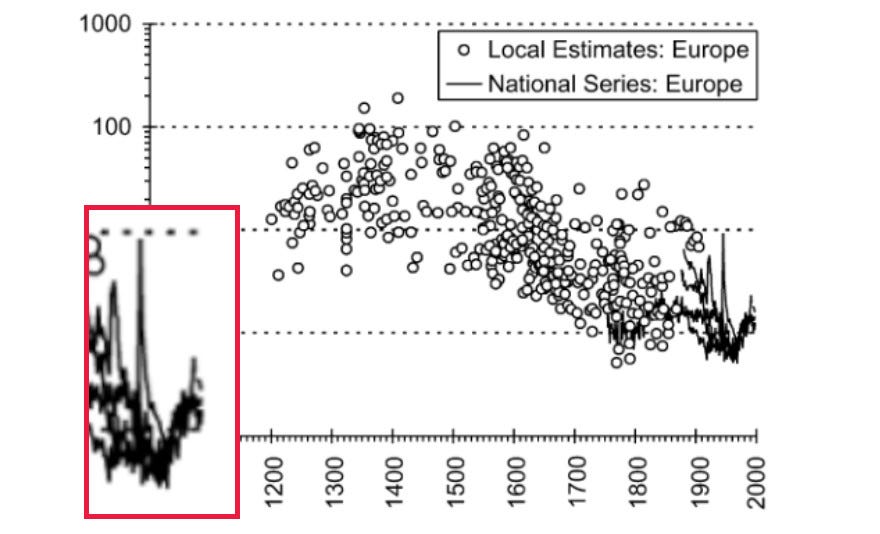

European crime rates in the long run, fromEisner 2003. Twentieth century magnified in the inset.

European crime rates in the long run, fromEisner 2003. Twentieth century magnified in the inset.

Interpersonal trust in the United States, fromOurWorldinData.org/trust

Interpersonal trust in the United States, fromOurWorldinData.org/trust

The point of this digression is just that it matters which is the right story of Western development, the landslide or the push.

A box of chocolates

I’ve been suggesting a critique, or waving my hand in the direction of one, but let me tell you how much there is in this book. There’s the introduction to the basic theory of cultural evolution – the psychology that lets humans have cultures and how ideas can transmit themselves down generations. There’s the definition of WEIRD psychology, including dispositionalism (the tendency to explain people’s actions by their innate character), and the tendency to categorize rabbits with cats not carrots; and the fact that even the famous Big Five traits of personality psychology don’t generalize very well beyond the WEIRD countries. There’s a taxonomy of the institutions that help human groups scale up their cooperation, starting with unilineal clans – the basic unit of intensive kinship, and the blind alley that most human societies got stuck in, on Henrich’s account – and including segmented lineages, age sets and premodern chiefdoms and states. (This is a very scientific, comparative approach to anthropology. I would love to hear a debate between Henrich and David Wengrow, whose book The Dawn of Everything , reviewed in ACX here, takes a much more voluntarist approach, starting from the view that there are many ways to organize a society, and that rational collective institutional design is pretty much a human universal.)

There’s the research programme of the psychology of religion, most famously exemplified in Ara Norenzayan’s Big Gods , with its human-like agents, divine monitoring, and Credibility Enhancing Displays. There’s the WEIRD kinship complex of bilateral descent, little to no cousin marriage, monogamy and nuclear families. There’s the history of the medieval church and its Marriage and Family Program, including the historical linguistics of words for relatives. There’s a big set of cross-country or cross-region regressions on “kinship intensity” – how clannish a society is – WEIRD pychology, the genetics of inbreeding and diplomats’ unpaid parking tickets. There’s the story of monogamy, how it affects testosterone, and how that might affect trust and conflict. There’s historical economic studies, usually with some clever natural experiment, on the medieval growth of institutions like fraternities, monasteries, universities, charter towns and the Law Merchant; and the plausible role of WEIRD psychology in each of these. Then the history of clocks, work hours, Cistercians, interest rates and apprenticeships. Last of all the development of law, science and Protestantism, again always with WEIRD psychology as a possible contributor, especially in building the networks – the collective brain – underpinning innovation. Across all of these areas, Henrich is always ready to jump sideways, to use a modern psychology experiment or a tribal ethnography to cast light on European history.

If you’re into these topics, this book is like a box of chocolates. You cannot possibly not learn something and come away with much to think about. Henrich is that rarity in academia, a real polymath, and that true academic unicorn, a polymath who makes his breadth of knowledge pay off.

What next?

Here are two open questions.

First, an unavoidable difficulty of the book is that it’s making claims about how human psychology affected history. But we can’t do psychological experiments on dead people. So sometimes, plausible ideas about how WEIRD psychology might have contributed to institution X (the monastery, science, clock time) are going to be very hard to test. As Henrich puts it, psychology is the “dark matter of history”, i.e., you can’t observe it directly.

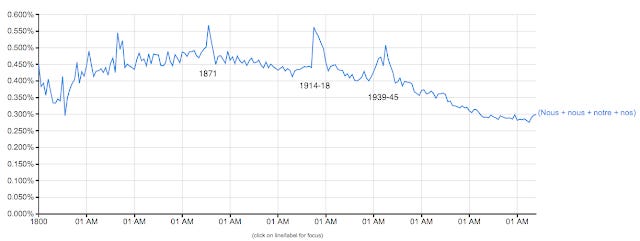

I wonder if there might be leeway to use texts as a way into historical psychology. We do now have large historical text corpuses available for mining. And there might be ways of relating them back to people’s psychology – like these guys who related human happiness to Google Books data. Just as a taster, here’s the occurrence of the French word for “we”, a plausible marker of group identity. See the spikes at the three major wars?

My biggest open question is: what next?

If monogamous marriage changes testosterone levels, what does the rise of serial monogamy do to that relationship? How does the WEIRD complex function when work disappears, if there’s a shortage of marriageable men and a mother might do better raising a kid herself – in the 90s in US cities, and today maybe in Ohio? If Jimmy Carter was an example of Protestant guilt culture when he said “I’ve looked on many women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times,” what does that culture look like in the age of Donald Trump? How will modern institutions react back on the WEIRD complex? There’s a famous answer that capitalism eats its own roots.

Meanwhile, what is happening in the non-Western world? I can imagine two replies to this. One corresponds to what people often say about the Iraq war: “you can’t just import institutions into a place where the culture isn’t ready”. You can tell this in a key of triumphalism – the West is always going to be richer, until the Rest of the world changes radically – or a key of despair – the Rest is never going to become democratic. At the end, briefly, the book seems to lean this way: “standard approaches to policy are poorly equipped to understand or deal with the institutional-psychological mismatches that arise from globalization.”

An alternative answer was put in a nice metaphor by Scott Alexander himself.

I am pretty sure there was, at one point, such a thing as western civilization. I think it included things like dancing around maypoles and copying Latin manuscripts…. That civilization is dead. It summoned an alien entity from beyond the void which devoured its summoner and is proceeding to eat the rest of the world.

In that story, when modernity arrives, it takes over everything. China goes modern, the rest of the world is going modern, and even the West itself is being fundamentally transformed. Again, this idea has its light and dark aspects. Fundamentally, it says that the landslide is now too big for any culture to avoid; the institutions of free markets, impersonal law, science and the modern state are coming for you, and they are strong enough now to transform your psychology on their own.

It seems important which of these two stories is true. So, after The Secret of Our Success and WEIRD , perhaps there is room to make it a trilogy.

-

But is it uniquely human? Some people think not.

-

In fact, Success and WEIRD were originally planned as one book.

-

It’s a bit more complex than that. In particular, the end of intensive kinship directly helps economic growth because it clears the way for voluntary associations to thrive. But the psychology angle is what’s really unique to WEIRD – in particular, Francis Fukuyama has previously argued that kin institutions might be a problem for higher-level cooperation.

-

Unintended consequences are basic to economics too. But in economics the actors are at least optimizing something , whereas for cultural evolution they are just following the rules they’ve learned.

-

Like with the poor kid in Brave New World , it turned out it was easier to make people parrot phrases than understand them: ‘“The-Nile-is-the-longest-river-in-Africa-and-the second-in-length-of-all-the-rivers-of-the-globe…” The words come rushing out…. “Well now, which is the longest river in Africa?” The eyes are blank. “I don’t know.”’