Your Book Review: The Wizard And The Prophet

[This is the seventh of many finalists in the book review contest. It’s not by me - it’s by an ACX reader who will remain anonymous until after voting is done, to prevent their identity from influencing your decisions. I’ll be posting about two of these a week for several months. When you’ve read all of them, I’ll ask you to vote for your favorite, so remember which ones you liked. If you like reading these reviews, check outpoint 3 here for a way you can help move the contest forward by reading lots more of them - SA]

Some books really stick with me. Like, literally, stick with me: I’m one of those people with pretentious literary tattoos. So far, just two books have been meaningful enough for me to permanently etch their totem on my skin: the glyph of the underground postal service from The Crying of Lot 49 , and the line “Everything Is Permitted,” Jean-Paul Sartre’s misquoting of Dostoevsky’s take on atheism from The Brothers Karamazov. (I wasn’t kidding about pretentious!) People have all sorts of reasons for getting tattoos – mine are there for some of the standard superficial ones (looking cool and tough, obviously), but also to act as little daily mantras for how I want to live and think about the world. To this very short list of inked paragons, I’m thinking of adding a new one: a few stylized stalks of wheat in honor of Charles Mann’s The Wizard and the Prophet.

According to the instructions on the tin, The Wizard and the Prophet is meant to outline the origin of two opposing attitudes toward the relationship between humans and nature through their genesis in the work and thought of two men: William Vogt, the “Prophet” polemicist who founded modern-day environmentalism, and Norman Borlaug, the “Wizard” agronomist who spearheaded the Green Revolution. Roughly speaking, Wizards want continual growth in human numbers and quality of life, and to use science and technology to get there: think Gene Roddenbury’s wildest dreams, full of replicators and quantum flux-harnessing doodads that untether us from our eons-long project of survival on limited resources and allow us to expand limitlessly. “Prophets’’ believe that we can’t keep growing our population or impact on the world without eventually destroying it, and ourselves along with it. Their ideal future is like one of those planets the Federation ships would Prime-Directive right over, where humankind scales back and lives in harmony with the land, taking just enough to sustain our (smaller) numbers and allowing the intricate web of human and non-human creatures to flourish.

Though Mann insists from the start that the book is not meant to advocate for or condemn either side, it was initially difficult for me to read it as anything but two-and-three-quarters cheers for Wizardry (more on the “initially” later). Part of this comes down to the challenge inherent in the genre: the book is structured first as a biography of Vogt and Borlaug (“Two Men”), then as an overview of how their Prophet and Wizard ideas play out in the modern-day battles over what to do about food, water, energy, and climate change (“Four Elements”). Starting the book with the personal and professional lives of these two men is a good way to show the very specific local contexts in which their ideas originated. Unfortunately, it’s also a good way to make Borlaug look like a saint, and Vogt like kind of an asshole.

Two Men

Vogt’s life begins in turn-of-the-19th-century Long Island, New York. At fourteen, he contracts polio, which leaves him with a Richard III-esque limp and drives him from his preferred leisure activity, hiking, to the gentlemanly sport of bird-watching. It is this hobby that brings him into contact with the nascent environmental movement of the 1930s, and soon he is doing unpaid field work, editing, and writing for various ecological societies on the East Coast. He becomes director of the Jones Beach State Bird Sanctuary in Long Island, where he notices the sudden dwindling in local bird populations and launches a polemical campaign against what he believes to be the culprit: government-sponsored public works projects to drain ditches and marshes and spray pesticides to control the mosquito population, intended to curb the spread of malaria. Vogt refers to these efforts as “‘perilously close to destructive government-sponsored rackets’” and uses his position as editor of the Audubon Society’s official publication, Bird-Lore, to lambast them with such venom that the president of the Audubon Society tells him to stop and, eventually, fires him. (Incidentally, the particular bird species Vogt was seeing decline and was so worried about, the dovekie, is currently listed as “least concern” on the conservation status scale, so I guess all that ditch-dredging and pesticide-spraying didn’t have much of a long-term impact. In his defense, though, dovekies are ridiculously cute.)

The face that launched modern-day environmentalism.

The face that launched modern-day environmentalism.

The fact that Vogt’s first entry into the public sphere is rallying the public against anti-malaria measures leaves a pretty bad taste in my mouth, as I’m sure it does for any of Mann’s Effective Altruist aligned readers. It would be one thing if Vogt were concerned about the detrimental impact of malaria on humans AND the detrimental impact of malaria prevention methods on bird life. But in subsequent chapters of Vogt’s biography, Mann goes out of his way to show that Vogt’s influences and contemporary members of the environmentalist milieu – for example, Madison Grant, co-founder of the Bronx Zoo, organizer of the United States national park system, and author of the charmingly named The Passing of the Great Race , beloved by Hitler – were, to put in mildly, extremely uninterested in the wellbeing of all humankind. Instead, they were obsessed by fears of an unchecked Malthusian population explosion, race mixing, and a resultant societal degeneration that could only be stopped by halting (read: starving out) population growth. Which people deserved to live in harmony with nature in the ensuing pastoral utopia and which would be relegated to the dustbin of history was not an exercise they left to the reader. Mann writes that Vogt, like his buddies, was “loudly scornful of the ‘unchecked spawning’ and ‘untrammeled copulation’ of ‘backward populations’ – people in India, he sneered, breed with ‘the irresponsibility of codfish.’”

The big shift Vogt makes to his contemporaries’ flavor of environmentalism is to turn from the specifics of racism, classism, and eugenics to generalized misanthropy. His subsequent writings – a report on the guano-producing bird population in Peru, surveys of ecology across South America, and especially his best-selling book Road to Survival – borrow from his predecessors’ racist-tinged doom-heralding and expand on it by chastising all humans, rich and poor, white and non-white alike. According to Mann, Vogt argues that “consumption driven by capitalism and rising human numbers is the ultimate cause of most of the world’s ecological problems, and only dramatic reductions in human fertility and economic activity will prevent a worldwide calamity.” Crucial to this is the concept of “carrying capacity” – the idea that the earth has a fixed capacity to support human and animal life.

When I was in elementary school in Seattle, my fourth-grade class was gifted a fishtank of salmon eggs to incubate and eventually return upstream, to teach us about the salmon life-cycle. The tank was packed with eggs, and once they hatched, it looked like salmon pandemonium in there, with barely enough room for the fry to move around without bumping into each other. In Vogt’s zero-sum view, the earth is like that salmon tank on a planetary scale; you can’t add new fish without displacing existing ones or diminishing their quality of life. Since Vogt sees the mid-twentieth century earth as being on the precipice of surpassing, if not already having surpassed, that capacity, he views everything being done to increase the numbers and consumption power of humans as a threat to this fragile ecosystem.

The problem with the concept of carrying capacity – impossible to define or know when we’ve surpassed, until after the proverbial moment when killing one mosquito or dovekie too many plunges us into everlasting fire and brimstone – is that it seems mostly like a mood affiliation thing. Consider this: when you look out at the bird feeder hanging in your backyard (Bay Area people living in closets, use your imagination here), do you see a blissful symbiotic coexistence of the human world and nature, with humans generously giving of our growth-accumulated abundance to help the birds flourish? Or do you see a dystopian struggle where innocent creatures pushed to the brink of death by our traffic and pesticides and housecats must rely on meager scraps for survival? There isn’t really a right view here, I don’t think, just a predilection for seeing what matches your intuition and telling a story about it. Given the life story Mann depicts for Vogt, it’s not hard to see why he would lean toward the pessimistic take. From the childhood marred by a philandering father who left his family in a cloud of scandal and ruin, to the adult life spent stumbling from one bourgeois non-occupation (theater critic, bird watcher, government mole rooting out Nazis in South America) to the next, to the childlessness and divorce, Vogt seems happiest when he is away from any humans, whether tromping through pre-suburbanized Long Island, or alone with the guano-producing birds on the desolate coast of Peru. Were he to live in an age of Facebook and Twitter, he would definitely be that guy reposting memes that COVID is finally letting our planet “heal.”

Borlaug’s section, in contrast, begins not in the rarefied world of middle-class New York, but on the unforgiving prairie of Saude, Iowa, which his poor Norwegian immigrant family tries to farm. He comes of age at roughly the same time as Vogt, but his early life may as well be mid-1800s Little House on the Prairie : Borlaug and his siblings literally have to walk three miles in the snow to get to their one-room schoolhouse. Fortunately, he is freed from a life of subsistence farming and given the chance to go to high school and college by his family’s purchase of a Ford tractor, which nicely sets up his lifelong optimism about the ability of technology to improve lives. While attending college in Minneapolis at the height of the Great Depression, Borlaug sees a crowd of striking dairy farmers being beaten by police and National Guardsmen for protesting the drop in the price of milk by surrounding a scab-driven milk truck. “Not all of the shouting men were farmers, Borlaug realized,” Mann writes. “Some of them were just hungry – famished men, women, and children, almost maddened by want.” Where Vogt might have curled his lip in distaste and gone home to write a pamphlet about this scene as an illustration of humanity’s taxing the earth’s carrying capacity and reaping the consequences, for Borlaug this was the catalyst for homing in on solving the problem of hunger. Mann: “Something must be done, he thought. Those famished people were ready to tear apart the world, and who could blame them? Here began, or so he said afterward, the work that would make him the original Wizard.”

In college, Borlaug first studies forestry, then gets seduced by plant biologist Elvin Charles Stakman’s personal crusade against stem rust, a fungus that blights wheat crops and, at the time, critically endangered the global wheat supply. After a brief stint as an industry research scientist at DuPont, in the 1940s Borlaug ends up as the unlikely candidate to lead a nascent rust study in Chapingo, Mexico. Borlaug is sent by his superiors essentially to sell the Mexican farmers on the more productive (but still rust-susceptible) American wheat strains. Instead, he takes the underfunded and under-resourced Chapingo project into an unexpected direction: after seeing that rust and variability in growing conditions would hamper any attempt to increase wheat crop yields in Mexico, he begins a series of years-long Mendelian cross-breeding pilots in four different locations of Mexico to find a prodigious, hardy wheat strain that is not only immune to rust, but can survive and thrive virtually no matter the location or growing conditions.

Despite lack of experience, no knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of genetics (which were yet to be discovered), skepticism from his superiors, suspicion from the Mexican farmers, and even Vogt’s attempt to shut the program down, Borlaug perseveres. After years of painstakingly cross-breeding hundreds of wheat strains from all around the world by hand, he finally stumbles on his miracle wheat, which sextuples the yield of the previous wheat cultivars in Mexico and turns the country into a wheat exporter virtually overnight. With Borlaug’s “package” of new wheat (and later, rice), modern synthetic fertilizer, and state-of-the-art agricultural science, a global famine – threatening not just Mexico, but the billions of people worldwide experiencing the post-WWII population boom – is averted, and farmers around the world can now feed orders of magnitude more people with less effort. For this, he wins the Nobel prize and timeless love and admira– …haha, just kidding. He does win a Nobel prize, but I think it’s safe to say that while some highly educated folks in some niche fields know what the Green Revolution is, outside of a few unassuming places in the Midwest, nobody is going to run into a statue of this guy in their town square.

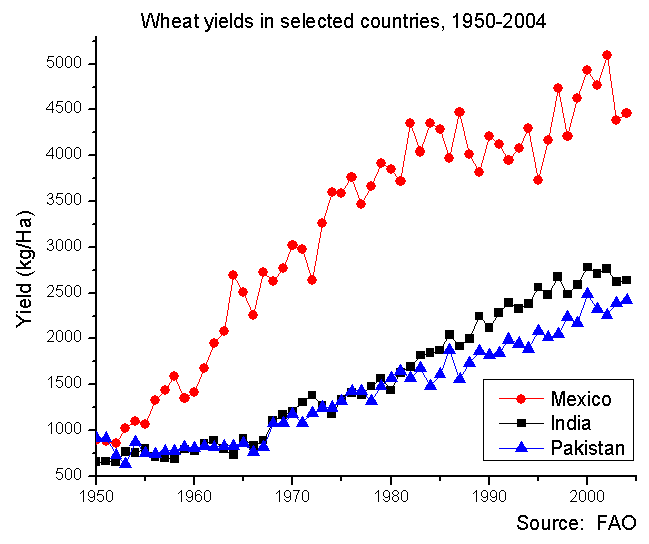

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any rationalist blog post must include a graph. Here’s a lovely one showing wheat yields post-Borlaug (his strains were made commercially available in the early 60s).

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any rationalist blog post must include a graph. Here’s a lovely one showing wheat yields post-Borlaug (his strains were made commercially available in the early 60s).

That’s really a shame, because if a person like Borlaug hadn’t actually existed, he would have had to have been invented for fictional purposes. Not only is he the antithesis of Vogt and company’s elitist ethnocentrism, he is also a devoted family man, humble eschewer of the spotlight, and diligent workhorse nerd. I suspect that Andy Weir had him in mind when writing The Martian , one of the greatest contemporary fictional paeons to the power of Wizardry. In fact, if you never read another thing about Borlaug, just picture Matt Damon single-handedly agro-engineering potatoes, virtually ex nihilo, in space.

Though Borlaug didn’t tend to wax philosophical like Vogt did, I think if he were to comment on the idea of carrying capacity, he would describe it as a fluid equilibrium that can be turned into a virtuous circle: find ways to feed more people, and their increased productivity pulls them and their countrymen out of poverty, increasing both quality of life and growth potential. The key is not to limit the number of people, but to not let the people starve and fall into ruin. To Borlaug, the earth is not a finite planet-sized fish tank, because humans aren’t fish; we can understand and engineer our way out of problems that a salmon fry can’t, and it’s our responsibility to use the tools at hand for the benefit of all.

By starting The Wizard and the Prophet with these two men and their lives, Mann sets up a dichotomy that’s difficult not to carry through the rest of the book. Vogt’s worldview is aligned with all the worst causes – elitism, white supremacy, and eugenics. Borlaug, on the other hand, seems to be guided by nothing other than the purest race-and-nation-blind agape for all mankind. Actually, dichotomy isn’t quite the right word; it’s more of a chiasmus, a trusty ancient Greek rhetorical device where the starting premises criss-cross to the delight and instruction of the audience. Vogt, the bourgeois coastal elite, wants to return the world to a primitive pastoral Eden. Borlaug, the blue-collar Midwesterner who grew up in an actual, non-idealized primitive pastoral setting, dreams of a world of bourgeois plenty for all.

Cult of personality aside, though, Vogt’s arguments may resonate with the utilitarians who believe that average utility matters more than total, so a world with fewer beings who lead happier lives is preferable to a world of unchecked growth that leads to worse outcomes for many individuals, human or dovekie. A version of this strain of thought is a perennial enough question to warrant its own FAQ item on the GiveWell blog. I think the revealed preference of most rationality/EA-aligned folks like me and probably many readers of this blog (as evidenced by the kinds of charitable causes we give to, like GiveWell) is more closely aligned with Borlaug and the Wizards: that it is important and possible to increase both average and total utility, both number of lives and quality of life. But even though it’s hard to imagine people today willingly deciding to stop reproducing above replacement or consuming goods for the sake of the mosquitos and dovekies (no matter how cute they are), it’s not unreasonable to think that as a normative matter, that world may in fact be a better one. The original Prophet solution to attaining that world by actively decreasing human populations may be less en vogue today what with eugenics and Malthusianism not exactly welcome topics in polite company, but it’s been replaced by other fears of overreaching capacity of one kind or another, be it oil, water, or greenhouse gases, and a desire to curb growth in these spheres and focus on conservation. Might there be some validity to the Prophets’ concerns that we can’t have it all (both average and total utility increases), and that we’re growing too quickly for our planet and its resources to keep up with us?

Four Elements

The second half of The Wizard and the Prophet explores four areas where humankind faces major dilemmas and needs some form of action (whether Wizardry or Prophetry) in order to survive. Mann names each chapter after one of the four elements: Earth (food), Water (self-explanatory), Fire (energy), and Air (climate change). Again, while Mann gives ample airtime to both worldviews and their proposed solutions, Wizards come out looking pretty good. Each chapter sees the Wizards demonstrate over and over that carrying capacity in these spheres is not fixed and can be altered by science and technology – earth through hacking photosynthesis to produce more abundant crop yields with the same soil and water inputs, water through desalination plants and massive public works projects to move water from more to less abundant environments, energy through better use of legacy fuel sources and finding new ones, and climate change through carbon capture. The Prophets, meanwhile, decry the dangers of both growth and Wizardry (insofar as it enables growth) and argue for social change that seems, at best, limited in impact, and at worst, impossible and ineffective. But the question remains: are we creating a better world by increasing global capacity with our Wizardly tricks, or are we overreaching and dragging down the quality of life around us?

In “Earth,” Mann focuses on the problem of how to continue to scale food production to meet the needs of an exponentially growing population. The Wizards already have quite a few impressive wins under their belt: in addition to Borlaug’s wheat, rice, and maize, there’s also creating synthetic fertilizer, which reduced the world’s reliance on natural but limited stocks of nitrogen-rich resources (like guano, which Vogt was tasked with studying in Peru before synthetic fertilizer became the cheap and obvious solution). For the future, the Wizards look to upgrade staple food crops to C4 photosynthesis (a more efficient way for plants to distinguish between hydrogen and carbon dioxide, requiring less water and nitrogen for the same yield). At the time Mann was writing The Wizard and the Prophet , C4 was still considered a whacky moonshot, but more recently it’s looking like we’re getting closer to making it happen. The Prophets, meanwhile, decry genetically modifying food as an abomination (despite, or maybe because of, the unyielding reassurance from scientists that it’s perfectly safe), insist that synthetic fertilizer used in industrial farming irreparably damages soil (the evidence for this claim seems mixed, though what most researchers appear to agree on is that the higher per-acre yield of synthetic fertilizer means less land needed for farming and thus less overall harm to the environment) and propose to feed the world with… local, organic farming? Years ago, I remember watching the first season of “America’s Next Top Model,” at the time the most interesting study of class divides in America. One of the contestants was a smart upper-class medical student. The sickest shade one of the other contestants, a Bible-thumping blue-collar Southern girl, thought to throw at her was asking what kind of pizza she liked and following it up with a sneering “… organic?” I think that, more than reams of evidence that Alice Waters style organic proselytizing does little to solve world hunger, pretty well sums up the rebuttal to this Prophet argument. Anti-GMO scaremongering aside, humanity seems pretty content to live off industrial globalized agriculture if it means pizza isn’t $50 a pop and only available to a rarefied population of coastal elites.

In “Water,” again, the Wizards have a solid track record. The Wizardly California State Water Project transformed a desert into the most productive farmland and state in the nation; the National Water Carrier Project of Israel-Palestine made life in the Fertile Crescent possible for millions of Jewish refugees. Desalination projects (expensive, but with nearly bottomless potential, given how huge our oceans are) have de-escalated the fight for shrinking groundwater resources in California and the Middle East. In this arena, the Prophets have been a little more successful in offering alternative conservation-oriented solutions that have stuck: storm and wastewater reclamation, drip irrigation, and behavioral change campaigns to encourage more frugal water usage that have seeped (pun intended) so deeply into the public consciousness that running the tap while brushing your teeth feels as illicit as lighting up a cigarette. All of these measures do little, though, to solve the fundamental underlying problem of massive urban growth in water-scarce areas like the American Sunbelt; if anything, growing water efficiency among consumers exacerbates the problem by shrinking utility profits and forcing them to either cut back on much-needed infrastructure repair and service improvement or raise water costs. Conservation and reclamation can only do so much; they can’t provide water to the exploding populations of Arizona or Sub-Saharan Africa.

I think not many people (especially not those that live there!) realize that California mostly looks like the yellowish-brownish parts of this picture, and also that it’s the number one agricultural producer in the US, ahead of what we typically think of as Corn Country or Beef Country of whatever. Thanks, Wizardry!

I think not many people (especially not those that live there!) realize that California mostly looks like the yellowish-brownish parts of this picture, and also that it’s the number one agricultural producer in the US, ahead of what we typically think of as Corn Country or Beef Country of whatever. Thanks, Wizardry!

In “Fire,” the line between Wizardry and Prophetry seems the most slippery – is solar power an example of a cutting-edge technological solution to a seemingly intractable growth problem (in which case it would be firmly in the Wizard camp) or an environmentally-friendly alternative to “dirty” Wizard technology like fracking and nuclear power plants (in which case, it should belong to the Prophets)? Mann places it more in the Prophet category, but an important point he makes is that, before fears of climate change displaced the locus of the argument surrounding oil, the Prophets’ party line was that alternative “clean” energy solutions like solar were desperately needed because the stock of oil in the world was running out – which so far has proven to be untrue. Much like “we’re running out of room for all these people!” or “we’re running out of space to house all this garbage!” this zombie conviction persisted for decades and seemed resistant to any evidence to the contrary. But if (big if!) carbon emission were of no concern, Wizards would have neatly won this fight through their development of more sophisticated oil extraction techniques and more energy-efficient machines, turning oil supply into a Zeno’s Paradox. Mann: “‘It is commonly asked, when will the world’s supply of oil be exhausted?’ wrote the MIT economist Morris Adelman. ‘The best one-word answer: never.’ On its face, this seems ridiculous – how could a finite stock be inexhaustible, when a constantly renewed flow can run out? But more than a century of experience has shown it to be true. […] That is, fossil fuel supplies have no known bounds.”

Finally, in “Air,” we get to the most (in my view, the only) ambivalent section of the book. First, unlike in the other “Elements” chapters, in “Air” the carrying capacity substance in question – excess atmospheric greenhouse gases – is a problem that the Wizards themselves created, partially to solve the problems in the other three chapters. Second, humanity has gone through a lot of local carrying capacity scares around food, water, and energy, and we’ve always managed to scrap our way through it, but climate change on a global scale hasn’t happened before to this degree (“Little Ice Age” notwithstanding) in modern history, so it’s easier to imagine it as that final straw that shows carrying capacity to be ominously real after all. Third, no one wants Snowpiercer world, where we employ some untested tool of Wizardry to solve a novel problem and end up on a literal doom train. At the time when Mann was writing The Wizard and the Prophet , it was still unclear whether the projected global warming figures would fall into the merely very bad range over the next century, or the X-risk-inducing range that would plunge us into a Vogt-style apocalypse. Three years and countless Integrated Assessment Models later, and it seems like it’s still unclear, except that “‘[w]e’ve ruled out ‘We’ll be fine,’ and we don’t think ‘doom’ is very likely.’” I and other Wizard-leaning people are hopeful that the combination of new energy efficient technologies and carbon capture and sequestration schemes will minimize the damage, but I recognize that it was probably the Prophets yelling at us for 50+ years that accelerated interest in these solutions, and they may not work quickly enough to avoid substantial lost lives and suffering.

I guess that’s as close to a steelman as I can get for Prophetry: while we’ve so far avoided hitting the carrying capacity limit on our imaginary earth-sized fish tank through Wizardly technologies, we can’t rest on our laurels and call it a day, because new inventions create new problems, and our continued success as a species or a planet is never guaranteed.

I was a Wizard once, but then I took an arrow to the knee. I mean… then COVID-19 happened.

If you had asked me before March 2020 whether I thought we could science our way out of a slow-grind, long-term disaster scenario like climate change, I would have said categorically yes. As long as we have some Borlaugs out there laser-focusing on the problem, there’s no actual danger that we’ll be constructing Waterworld-style life rafts over the flooded remnants of our formerly glorious civilization. But, uh, I’m no longer so sure.

I’m convinced, to be clear, that we have a lot of Borlaugs out there – the pioneers of mRNA who produced vaccines to a novel virus in world-record time surely fit the bill, whether they’re hardscrabble farmers from Iowa with hearts of gold or not. But we also have a lot more fish in a much bigger, fancier tank now than in Borlaug’s day. According to hard Wizardry, all that increased productivity and human capital should have made it easier for us to roll up our sleeves and nip this thing in the bud; instead, we all collectively shat the bed. It wasn’t just red states or populist leaders or microchip truthers that were guilty; everyone in every country, state, and Holy See didn’t adopt masks, close the borders, roll out tests, or vaccinate quickly and effectively enough, and the blood of 2 million people and counting (not to mention the global loss of jobs, social activities, educational quality, and basic human connection) is on our hands. Unlike climate change, pandemics aren’t even a new problem we’ve never encountered, and certainly not a problem Wizards weren’t aware of and politely screaming about for years. So how could we have been caught so off-guard and been so slow and ineffective at responding?

If you look around, you’ll see lots of other COVID-like problems out there that are quietly but inexorably claiming lives and dragging down average utility worldwide – poverty, homelessness, economic stagnation – that Wizards haven’t found good solutions for. I don’t think it’s from a lack of trying; I think we may have hit a carrying capacity limit on our ability to deal with complexity. Systems in the modern world are complex. No, really complex. No, even more complex than that. Consider all of the different systems that interacted to form the giant clusterfuck that is the COVID-19 pandemic response: local politics, global politics, scientific knowledge production, scientific knowledge dissemination, the media, social media, business, regulations, logistics chains. Each of these contain multitudes of factors that no single human on earth, not even the Normanest of Borlaugs, could keep straight in his or her head and “fix” with a single quick hack like a better strain of wheat. And these complex systems aren’t just statically complex – they seem to be getting more complex over time in their interactions with each other. In the 1960s, Borlaug’s new wheat strain was used by virtually all Mexican farmers a year after it was released commercially; if it had been created today, it probably would have sat on a shelf for a decade while various global FDA-like agencies dickered over whether it was safe or not and anti-GMO groups launched a thousand frankenwheat memes; you’d definitely never be able to buy it at Whole Foods.

In Caliban’s War , the second book in The Expanse series, there’s an excellent metaphor for how having more smart people working on problems fails in an atmosphere of increased complexity, offered by fictional future UN government higher-up Chrisjen Avasarala: “You take part of a problem and you put it somewhere, get some people working on it, and then you get another part of the problem and get other people working on that. And pretty soon you have seven, eight, a hundred different little boxes with work going on, and no one talking to anyone because it would break security protocol.” Except instead of security protocol, you could substitute any number of Moloch-y reasons, or just regular old-fashioned human tunnel vision. If there’s one thing we can take from the Prophets, it’s their focus on trying to understand complex systems holistically , Chesterton’s Fence style, instead of as piecemeal problem-boxes in a hundred siloed experts’ rooms. Each of today’s systems is more like Chesterton’s Maze of Forking Paths, where pulling out a brick here (say, trying to prioritize equity in vaccine distribution) leads to a catastrophic tunnel collapse there (more deaths, including in the historically underprivileged populations you were trying to save). The Prophets may have a less than stellar track record of questioning new technologies, but I think they’re right that the Wizardly tendency to reduce complexity to a discrete number of problem-boxes can only get us so far – and, as we saw with the myriad of expert box factories talking past each other in the global COVID pandemic response, it can harm as well as help. If we’re always hotfixing as our big picture grows bigger and more complex, we’re also always creating new inadvertent problems with our hotfixes, and are in ever more danger of forgetting about that one critical problem box until it’s too late.

It is also a truth universally acknowledged that any rationality blog post must include an XKCD comic.

It is also a truth universally acknowledged that any rationality blog post must include an XKCD comic.

A friend of mine who works in politics thinks there’s a third kind of archetype we seem to be missing in the Wizard/Prophet dichotomy – something like the “Engineer” who can tinker with complex, semi-broken systems using a mix of Wizardly tools (science, technology, RCTs) and Prophetic ones (grass-roots activism, behavioral and cultural change) to get them retuned and producing better long term outputs. Another in academia thinks genetically engineering everyone to be smarter is the only way to make real progress on the thornier, hairier systemic problems. Half the people I know in the Bay Area are convinced that democratic socialism is the true path forward; the other half are pretty sure that AI will eventually, not-too-distantly-from-now destroy everything, so other kinds of long term systems tinkering probably aren’t even worth worrying about. (It’s interesting to me that the realm of AI research is populated by highly educated, technocratic Wizard types, but while its tenor may have started out very Wizardly, it is now extremely Prophetic.)

To a greater or lesser degree, I believe in some of these things (except socialism… sorry, guys). But here’s what I also know, deep down in my bones: we have to keep trying to make things better, and we can’t let a little (or a lot of) complexity stop us. We engineered our way into this world of ours with Wizardry, by systematically analyzing it and testing it and improving it. It started with the simple trial and error of our prehistoric ancestors, and it continues today in labs and offices and think tanks they never could have imagined. Like our ancestors, we’ve made mistakes along the way – but now, our fish tank is bigger and the stakes are much, much higher: instead of poisoning a family by eating the wrong mushroom, we now have the ability to wipe out entire species, including ours. Or save them.

That’s why, ultimately, the image I take away from The Wizard and the Prophet is Borlaug (Norm-boy, as his family called him) bent over his blighted wheat fields in Chapingo. Sunburned and soaked in sweat. Knowing that he’s failing – that he’s failed countless times and will fail again – he stoops next to each stalk and continues to look for ways to coax it to life. Maybe the Korean strain mixed with the Nigerian one? Maybe Japanese and American? A tall, lanky Norwegian-American broiling under the Mexican sun, seeds from a dozen countries in his blistered hands, just trying to do the right damn thing. Even if all of humanity is wiped out by COVID-22 or some other unforeseen catastrophe, and even if there’s no god above us to judge us by our actions, that is the most fitting testament I can think of to the spirit of what humanity was, is, and ever should be. Also, it’s the most badass tattoo I can imagine.