Yudkowsky Contra Christiano On AI Takeoff Speeds

Previously in series: Yudkowsky Contra Ngo On Agents, Yudkowsky Contra Cotra On Biological Anchors

Prelude: Yudkowsky Contra Hanson

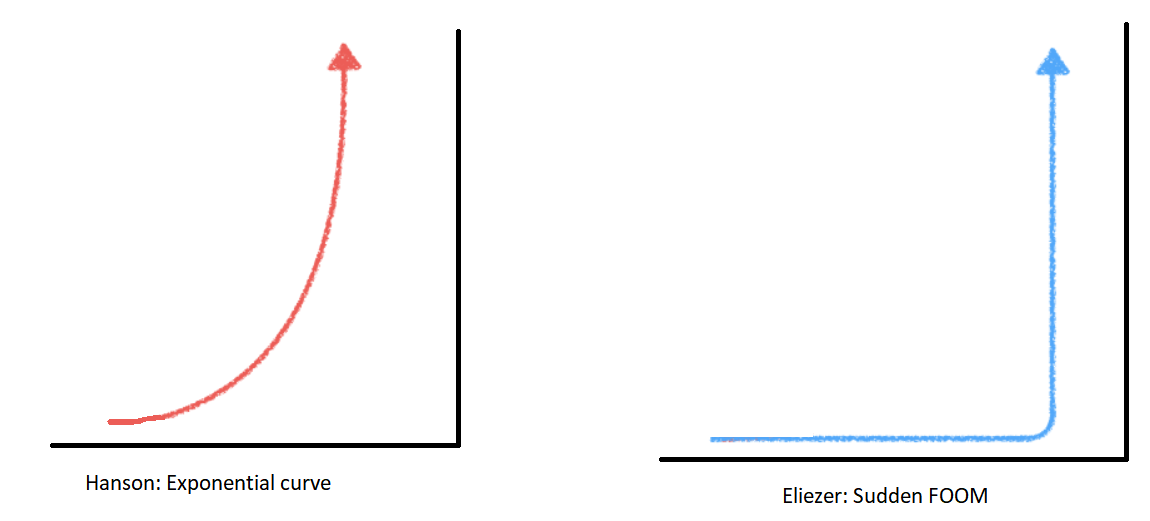

In 2008, thousands of blog readers - including yours truly, who had discovered the rationality community just a few months before - watched Robin Hanson debate Eliezer Yudkowsky on the future of AI.

Robin thought the AI revolution would be a gradual affair, like the Agricultural or Industrial Revolutions. Various people invent and improve various technologies over the course of decades or centuries. Each new technology provides another jumping-off point for people to use when inventing other technologies: mechanical gears → steam engine → railroad and so on. Over the course of a few decades, you’ve invented lots of stuff and the world is changed, but there’s no single moment when “industrialization happened”.

Eliezer thought it would be lightning-fast. Once researchers started building human-like AIs, some combination of adding more compute, and the new capabilities provided by the AIs themselves, would quickly catapult AI to unimaginably superintelligent levels. The whole process could take between a few hours and a few years, depending on what point you measured from, but it wouldn’t take decades.

You can imagine the graph above as being GDP over time, except that Eliezer thinks AI will probably destroy the world, which might be bad for GDP in some sense. If you come up with some way to measure (in dollars) whatever kind of crazy technologies AIs create for their own purposes after wiping out humanity, then the GDP framing will probably work fine.

For transhumanists, this debate has a kind of iconic status, like Lincoln-Douglas or the Scopes Trial. But Robin’s ideas seem a bit weird now (they also seemed a bit weird in 2008) - he thinks AIs will start out as uploaded human brains, and even wrote an amazing science-fiction-esque book of predictions about exactly how that would work. Since machine learning has progressed a lot faster than brain uploading has, this is looking less likely and probably makes his position less relevant than in 2008. The gradualist torch has passed to Paul Christiano, who wrote a 2018 post Takeoff Speeds revisiting some of Hanson’s old arguments and adding new ones.

(I didn’t realize this until talking to Paul, but “holder of the gradualist torch” is a relative position - Paul still thinks there’s about a 1/3 chance of a fast takeoff.)

Around the end of last year, Paul and Eliezer had a complicated, protracted, and indirect debate, culminating in a few hours on the same Discord channel. Although the real story is scattered over several blog posts and chat logs, I’m going to summarize it as if it all happened at once.

Gradatim Ferociter

Paul sums up his half of the debate as:

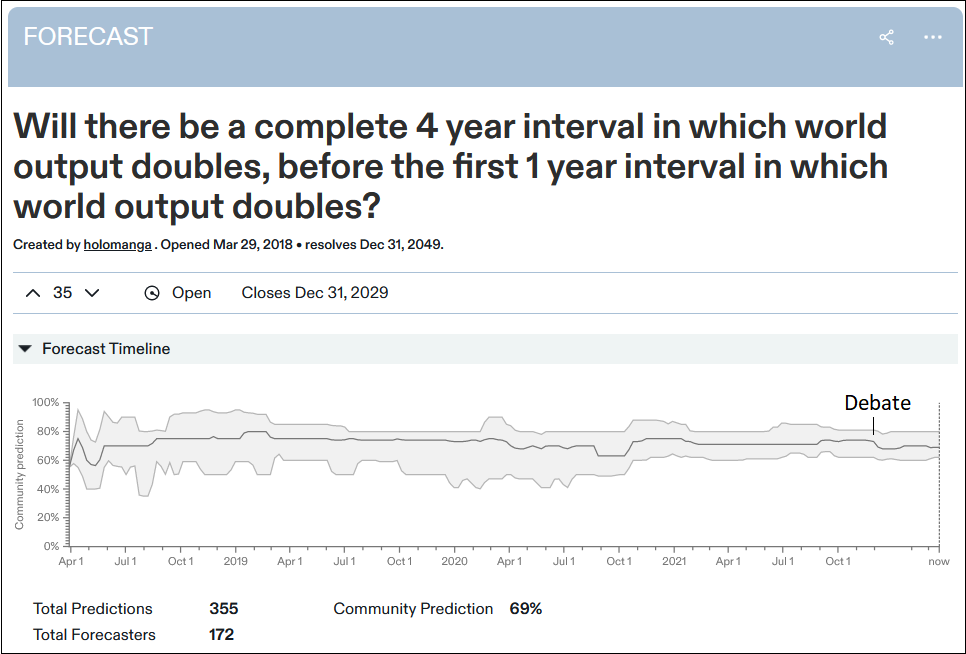

There will be a complete 4 year interval in which world output doubles, before the first 1 year interval in which world output doubles. (Similarly, we’ll see an 8 year doubling before a 2 year doubling, etc.)

That is - if any of this “transformative AI revolution” stuff is right at all, then at some point GDP is going to go crazy (even if it’s just GDP as measured by AIs, after humans have been wiped out). Paul thinks it will go crazy slowly. Right now world GDP doubles every ~25 years. Paul thinks it will go through an intermediate phase (doubles within 4 years) before it gets to a truly crazy phase (doubles within 1 year).

Why? Partly based on common sense. Whenever you can build a cool thing at time T, probably you could build a slightly less cool version at time T-1. And slightly less cool versions of cool things are still pretty cool, so there shouldn’t be many cases where a completely new and transformative thing starts existing without any meaningful precursors.

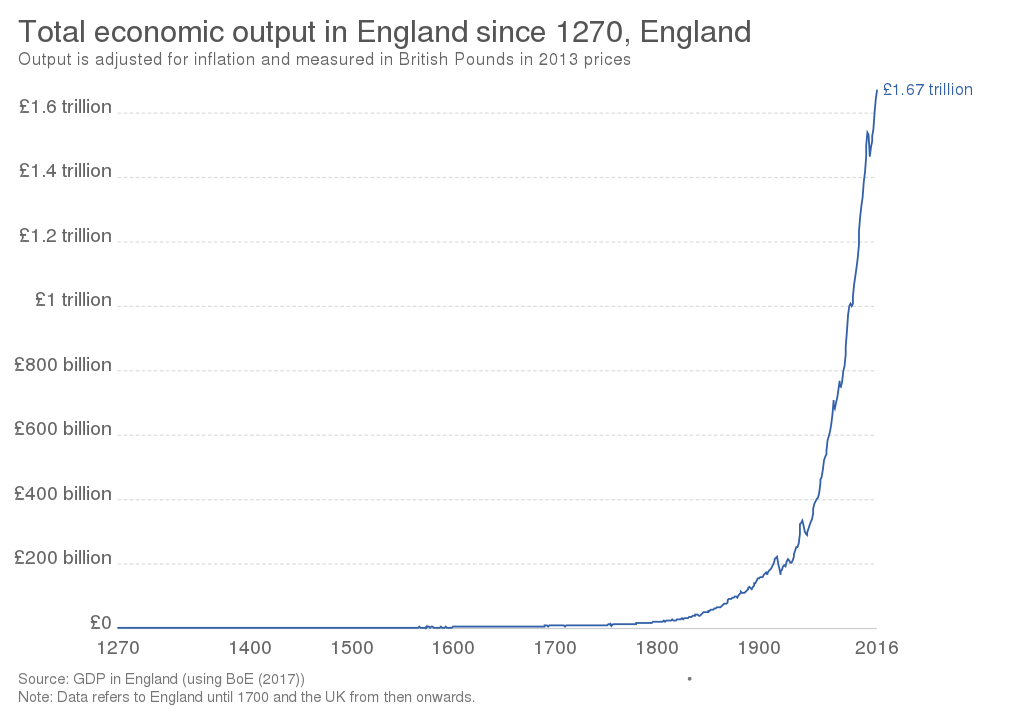

But also because this is how everything always works. Here’s the history of British GDP:

Industrial Revolution? What Industrial Revolution? This is just a nice smooth exponential curve.

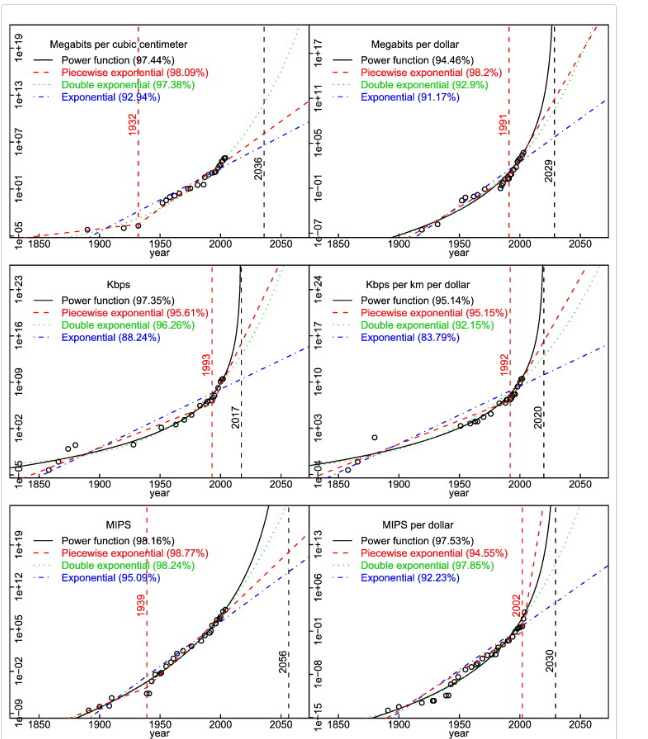

The same is usually true of individual technologies; Paul doesn’t give specifics, but Nintil and Katja Grace both have lots of great examples:

Information technologies over time (Nagy)

Information technologies over time (Nagy)

Chess AI performance over time.

Chess AI performance over time.

Why does this matter?

If there’s a slow takeoff (ie gradual exponential curve), it will become obvious that some kind of terrifying transformative AI revolution is happening, before the situation gets apocalyptic. There will be time to prepare, to test slightly-below-human AIs and see how they respond, to get governments and other stakeholders on board. We don’t have to get every single thing right ahead of time. On the other hand, because this is proceeding along the usual channels, it will be the usual variety of muddled and hard-to-control. With the exception of a few big actors like the US and Chinese government, and maybe the biggest corporations like Google, the outcome will be determined less by any one agent, and more by the usual multi-agent dynamics of political and economic competition. There will be lots of opportunities to affect things, but no real locus of control to do the affecting.

If there’s a fast takeoff (ie sudden FOOM), there won’t be much warning. Conventional wisdom will still say that transformative AI is thirty years away. All the necessary pieces (ie AI alignment theory) will have to be ready ahead of time, prepared blindly without any experimental trial-and-error, to load into the AI as soon as it exists. On the plus side, a single actor (whoever has this first AI) will have complete control over the process. If this actor is smart (and presumably they’re a little smart, or they wouldn’t be the first team to invent transformative AI), they can do everything right without going through the usual government-lobbying channels.

So the slower a takeoff you expect, the less you should be focusing on getting every technical detail right ahead of time, and the more you should be working on building the capacity to steer government and corporate policy to direct an incoming slew of new technologies.

Yudkowsky Contra Christiano

Eliezer counters that although progress may retroactively look gradual and continuous when you know what metric to graph it on, it doesn’t necessarily look that way in real life by the measures that real people care about.

(one way to think of this: imagine that an AI’s effective IQ starts at 0.1 points, and triples every year, but that we can only measure this vaguely and indirectly. The year it goes from 5 to 15, you get a paper in a third-tier journal reporting that it seems to be improving on some benchmark. The year it goes from 66 to 200, you get a total transformation of everything in society. But later, once we identify the right metric, it was just the same rate of gradual progress the whole time. )

So Eliezer is much less impressed by the history of previous technologies than Paul is. He’s also skeptical of the “GDP will double in 4 years before it doubles in 1” claim, because of two contingent disagreements and two fundamental disagreements.

The first contingent disagreement: government regulations make it hard to deploy imperfect things, and non-trivial to deploy things even after they’re perfect. Eliezer has non-jokingly said he thinks AI might destroy the world before the average person can buy a self-driving car. Why? Because the government has to approve self-driving cars (and can drag its feet on that), but the apocalypse can happen even without government approval. In Paul’s model, sometime long before superintelligence we should have AIs that can drive cars, and that increases GDP and contributes to a general sense that exciting things are going on. Eliezer says: fine, what if that’s true? Who cares if self-driving cars will be practical a few years before the world is destroyed? It’ll take longer than that to lobby the government to allow them on the road.

The second contingent disagreement: superintelligent AIs can lie to us. Suppose you have an AI which wants to destroy humanity, whose IQ is doubling every six months. Right now it’s at IQ 200, and it suspects that it would take IQ 800 to build a human-destroying superweapon. Its best strategy is to lie low for a year. If it expects humans would turn it off if they knew how close it was to superweapons, it can pretend to be less intelligent than it really is. The period when AIs are holding back so we don’t discover their true power level looks like a period of lower-than-expected GDP growth - followed by a sudden FOOM once the AI gets its superweapon and doesn’t need to hold back.

So even if Paul is conceptually right and fundamental progress proceeds along a nice smooth curve, it might not look to us like a nice smooth curve, because regulations and deceptive AIs could prevent mildly-transformative AI progress from showing up on graphs, but wouldn’t prevent the extreme kind of AI progress that leads to apocalypse. To an outside observer, it would just look like nothing much changed, nothing much changed, nothing much changed, and then suddenly, FOOM.

But even aside from this, Eliezer doesn’t think Paul is conceptually right! He thinks that even on the fundamental level , AI progress is going to be discontinuous. It’s like a nuclear bomb. Either you don’t have a nuclear bomb yet, or you do have one and the world is forever transformed. There is a specific moment at which you go from “no nuke” to “nuke” without any kind of “slightly worse nuke” acting as a harbinger.

He uses the example of chimps → humans. Evolution has spent hundreds of millions of years evolving brainier and brainier animals (not teleologically, of course, but in practice). For most of those hundreds of millions of years, that meant the animal could have slightly more instincts, or a better memory, or some other change that still stayed within the basic animal paradigm. At the chimp → human transition, we suddenly got tool use, language use, abstract thought, mathematics, swords, guns, nuclear bombs, spaceships, and a bunch of other stuff. The rhesus monkey → chimp transition and the chimp → human transition both involved the same ~quadrupling of neuron number, but the former was pretty boring and the latter unlocked enough new capabilities to easily conquer the world. The GPT-2 → GPT-3 transition involved centupling parameter count. Maybe we will keep centupling parameter count every few years, and most times it will be incremental improvement, and one time it will conquer the world.

But even talking about centupling parameter points is giving Paul too much credit. Lots of past inventions didn’t come by quadrupling or centupling something, they came by discovering “the secret sauce”. The Wright brothers (he argues) didn’t make a plane with 4x the wingspan of the last plane that didn’t work, they invented the first plane that could fly at all. The Hiroshima bomb wasn’t some previous bomb but bigger, it was what happened after a lot of scientists spent a long time thinking about a fundamentally different paradigm of bomb-making and brought it to a point where it could work at all. The first transformative AI isn’t going to be GPT-3 with more parameters, it will be what happens after someone discovers how to make machines truly intelligent.

(this is the same debate Eliezer had with Ajeya over the Biological Anchors post; have I mentioned that Ajeya and Paul are married?)

Fine, Let’s Nitpick The Hell Out Of The Chimps Vs. Humans Example

This is where the two of them end up, so let’s follow.

Between chimps and humans, there were about seven million years of intermediate steps. These had some human capabilities, but not others. IE homo erectus probably had language, but not mathematics, and in terms of taking over the world it did make it to most of the Old World but was less dominant than moderns.

But if we say evolutionary history started 500 million years ago (the Cambrian), and AI history started with the Dartmouth Conference in 1955, then the equivalent of 7 million years of evolutionary history is 1 year of AI history. In the very very unlikely and forced comparison where evolutionary history and AI history go at the same speed, there will be only about a year between chimp-level and human-level AIs. A chimp-level AI probably can’t double GDP, so this would count as a fast takeoff by Paul’s criterion.

But even more than that, chimp → human feels like a discontinuity. It’s not just “animals kept getting smarter for hundreds of millions of years, and then ended up very smart indeed”. That happened for a while, and then all of sudden there was a near-instant phase transition into a totally different way of using intelligence with completely new abilities. If AI worked like this, we would have useful toys and interesting specialists for a few decades, until suddenly someone “got it right”, completed the package that was necessary for “true intelligence”, and then we would have a completely new category of thing.

Paul admits this analogy is awkward for his position. He answers:

Chimp evolution is not primarily selecting for making and using technology, for doing science, or for facilitating cultural accumulation. The task faced by a chimp is largely independent of the abilities that give humans such a huge fitness advantage. It’s not completely independent—the overlap is the only reason that evolution eventually produces humans—but it’s different enough that we should not be surprised if there are simple changes to chimps that would make them much better at designing technology or doing science or accumulating culture […]

So I don’t think the example of evolution tells us much about whether the continuous change story applies to intelligence. This case is potentially missing the key element that drives the continuous change story—optimization for performance. Evolution changes continuously on the narrow metric it is optimizing, but can change extremely rapidly on other metrics. For human technology, features of the technology that aren’t being optimized change rapidly all the time. When humans build AI, they will be optimizing for usefulness, and so progress in usefulness is much more likely to be linear.

That is, evolution wasn’t optimizing for tool use/language/intelligence, so we got an “overhang” where chimps could potentially have been very good at these, but evolution never bothered “closing the circuit” and turning those capabilities “on”. After a long time, evolution finally blundered into an area where marginal improvements in these capacities improved fitness, so evolution started improving them and it was easy.

Imagine a company which, through some oversight, didn’t have a Sales department. They just sat around designing and manufacturing increasingly brilliant products, but not putting any effort into selling them. Then the CEO remembers they need a Sales department, starts one up, and the company goes from moving near zero units to moving millions of units overnight. It would look like the company had “suddenly” developed a “vast increase in capabilities”. But this is only possible when a CEO who is weirdly unconcerned about profit forgets to do obvious profit-increasing things for many years.

This is Paul’s counterargument to the chimp analogy. Evolution isn’t directly concerned about various intellectual skills; it only wants them in the unusual cases where they’ll contribute to fitness on the margin. AI companies will be very concerned about various intellectual skills. If there’s a trivial change that can make their product 10x better, they’ll make it. So AI capabilities will grow in a “well-rounded” way, there won’t be any “overhangs”, and there won’t be any opportunities for a sudden overhang-solving phase transition with associated new-capability development like with chimps → humans.

Eliezer answers:

Chimps are nearly useless because they’re not general, and doing anything on the scale of building a nuclear plant requires mastering so many different nonancestral domains that it’s no wonder natural selection didn’t happen to separately train any single creature across enough different domains that it had evolved to solve every kind of domain-specific problem involved in solving nuclear physics and chemistry and metallurgy and thermics in order to build the first nuclear plant in advance of any old nuclear plants existing.

Humans are general enough that the same braintech selected just for chipping flint handaxes and making water-pouches and outwitting other humans, happened to be general enough that it could scale up to solving all the problems of building a nuclear plant - albeit with some added cognitive tech that didn’t require new brainware, and so could happen incredibly fast relative to the generation times for evolutionarily optimized brainware.

Now, since neither humans nor chimps were optimized to be “useful” (general), and humans just wandered into a sufficiently general part of the space that it cascaded up to wider generality, we should legit expect the curve of generality to look at least somewhat different if we’re optimizing for that.

Eg, right now people are trying to optimize for generality with AIs like Mu Zero and GPT-3.

In both cases we have a weirdly shallow kind of generality. Neither is as smart or as deeply general as a chimp, but they are respectively better than chimps at a wide variety of Atari games, or a wide variety of problems that can be superposed onto generating typical human text.

They are, in a sense, more general than a biological organism at a similar stage of cognitive evolution, with much less complex and architected brains, in virtue of having been trained, not just on wider datasets, but on bigger datasets using gradient-descent memorization of shallower patterns, so they can cover those wide domains while being stupider and lacking some deep aspects of architecture.

It is not clear to me that we can go from observations like this, to conclude that there is a dominant mainline probability for how the future clearly ought to go and that this dominant mainline is, “Well, before you get human-level depth and generalization of general intelligence, you get something with 95% depth that covers 80% of the domains for 10% of the pragmatic impact”.

…or whatever the concept is here, because this whole conversation is, on my own worldview, being conducted in a shallow way relative to the kind of analysis I did in Intelligence Explosion Microeconomics, where I was like, “here is the historical observation, here is what I think it tells us that puts a lower bound on this input-output curve”.

Here Eliezer sort of kind of grants Paul’s point that AIs will be optimized for generality in a way chimps aren’t, but points to his previous “Intelligence Explosion Microeconomics” essay to argue that we should expect a fast takeoff anyway. IEM has a lot of stuff in it, but one key point is that instead of using analogies to predict the course of future AI, we should open that black box and try to actually reason about how it will work, in which case we realize that recursive self-improvement common-sensically has to cause an intelligence explosion.

I am sort of okay with this, but I feel like a commitment to avoiding analogies should involve not bringing up the chimp-human analogy further, which Eliezer continues to do, quite a lot. I do feel like Paul succeeded in convincing me that we shouldn’t place too much evidential weight on it.

The Wimbledon Of Reference Class Tennis

“Reference class tennis” is an old rationalist idiom for people throwing analogies back and forth.

“AI will be slow, because it’s an economic transition like the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, and those were slow!”

“No, AI will be fast, because it’s an evolutionary step like chimps → humans, and that was fast!”

“No, AI will be slow, because it’s an invention, like the computer, and computers were invented piecemeal and required decades of innovation to be useful.”

“No, AI will be fast, because it’s an invention, like the nuclear bomb, and nuclear bombs went from impossible to city-killing in a single day.”

“No, AI will be slow, because it will be surrounded by a shell-like metallic computer case, which makes it like a turtle, and turtles are slow.”

“No, AI will be fast, because it’s dangerous and powerful, like a tiger, and tigers are fast!”

And so on.

Comparing things to other things is a time-tested way of speculating about them. But there are so many other things to compare to that you can get whatever result you want. This is the failure mode that the term “reference class tennis” was supposed to point to.

Both participants in this debate are very smart and trying their hardest to avoid reference-class tennis, but neither entirely succeeds.

Eliezer’s preferred classes are Bitcoin (“there wasn’t a cryptocurrency developed a year before Bitcoin using 95% of the ideas which did 10% of the transaction volume”), nukes, humans/chimps, the Wright Brothers, AlphaGo (which really was a discontinuous improvement on previous Go engines), and AlphaFold (ditto for proteins).

Paul’s preferred classes are the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions, chess engines (which have gotten better along a gradual, well-behaved curve), all sorts of inventions like computers and ships (likewise), and world GDP.

Eliezer already listed most of these in his Intelligence Explosion Microeconomics paper in 2013, and concluded that the space of possible analogies was contradictory enough that we needed to operate at a higher level. Maybe so, but when someone lobs a reference class tennis ball at you, it’s hard to resist the urge to hit it back.

Recursive Self-Improvement

This is where I think Eliezer most wants to take the discussion. The idea is: once AI is smarter than humans, it can do a superhuman job of developing new AI. In his Microeconomics paper, he writes about an argument he (semi-hypothetically) had with Ray Kurzweil about Moore’s Law. Kurzweil expected Moore’s Law to continue forever, even after the development of superintelligence. Eliezer objects:

Suppose we were dealing with minds running a million times as fast as a human, at which rate they could do a year of internal thinking in thirty-one seconds, such that

the total subjective time from the birth of Socrates to the death of Turing

would pass in 20.9 hours. Do you still think the best estimate for how long

it would take them to produce their next generation of computing hardware

would be 1.5 orbits of the Earth around the Sun?

That is: the fact that it took 1.5 years for transistor density to double isn’t a natural law. It’s pointing to a law that the amount of resources (most notably intelligence) that civilization focused on the transistor-densifying problem equalled the amount it takes to double it every 1.5 years. If some shock drastically changed available resources (by eg speeding up human minds a million times), this would change the resources involved, and the same laws would predict transistor speed doubling in some shorter amount of time (naively 0.000015 years, although realistically at that scale other inputs would dominate).

So when Paul derives clean laws of economics showing that things move along slow growth curves, Eliezer asks: why do you think they would keep doing this when one of the discoveries they make along that curve might be “speeding up intelligence a million times”?

(Eliezer actually thinks improvements in the quality of intelligence will dominate improvements in speed - AIs will mostly be smarter, not just faster - but speed is a useful example here and we’ll stick with it)

Paul answers:

Summary of my response: Before there is AI that is great at self-improvement there will be AI that is mediocre at self-improvement.

Powerful AI can be used to develop better AI (amongst other things). This will lead to runaway growth.

This on its own is not an argument for discontinuity: before we have AI that radically accelerates AI development, the slow takeoff argument suggests we will have AI that significantly accelerates AI development (and before that, slightly accelerates development). That is, an AI is just another, faster step in the hyperbolic growth we are currently experiencing, which corresponds to a further increase in rate but not a discontinuity (or even a discontinuity in rate).

The most common argument for recursive self-improvement introducing a new discontinuity seems be: some systems “fizzle out” when they try to design a better AI, generating a few improvements before running out of steam, while others are able to autonomously generate more and more improvements. This is basically the same as the universality argument in a previous section.

Eliezer:

Oh, come on. That is straight-up not how simple continuous toy models of RSI work. Between a neutron multiplication factor of 0.999 and 1.001 there is a very huge gap in output behavior.

Outside of toy models: Over the last 10,000 years we had humans going from mediocre at improving their mental systems to being (barely) able to throw together AI systems, but 10,000 years is the equivalent of an eyeblink in evolutionary time - outside the metaphor, this says, “A month before there is AI that is great at self-improvement, there will be AI that is mediocre at self-improvement.”

(Or possibly an hour before, if reality is again more extreme along the Eliezer-Hanson axis than Eliezer. But it makes little difference whether it’s an hour or a month, given anything like current setups.)

This is just pumping hard again on the intuition that says incremental design changes yield smooth output changes, which (the meta-level of the essay informs us wordlessly) is such a strong default that we are entitled to believe it if we can do a good job of weakening the evidence and arguments against it.

And the argument is: Before there are systems great at self-improvement, there will be systems mediocre at self-improvement; implicitly: “before” implies “5 years before” not “5 days before”; implicitly: this will correspond to smooth changes in output between the two regimes even though that is not how continuous feedback loops work.

I got a bit confused trying to understand the criticality metaphor here. There’s no equivalent of neutron decay, so any AI that can consistently improve its intelligence is “critical” in some sense.

Imagine Elon Musk replaces his brain with a Neuralink computer which - aside from having read-write access - exactly matches his current brain in capabilities. Also he becomes immortal. He secludes himself from the world, studying AI and tinkering with his brain’s algorithms. Does he become a superintelligence? I think under the assumptions Paul and Eliezer are using, eventually maybe. After some amount of time he’ll come across a breakthrough he can use to increase his intelligence. Then, armed with that extra intelligence, he’ll be able to pursue more such breakthroughs. However intelligent the AI you’re scared of is, Musk will get there eventually.

How long will it take? A good guess might be “years” - Musk starts out as an ordinary human, and ordinary humans are known to take years to make breakthroughs.

Suppose it takes Musk one year to come up with a first breakthrough that raises his IQ 1 point. How long will his second breakthrough take?

It might take longer, because he has picked the lowest-hanging fruit, and all the other possible breakthroughs are much harder.

Or it might take shorter, because he’s slightly smarter than he was before, and maybe some extra intelligence goes a really long way in AI research.

The concept of an intelligence explosion seems to assume the second effect dominates the first. This would match the observation that human researchers, who aren’t getting any smarter over time, continue making new discoveries. That suggests the range of possible discoveries at a given intelligence level is pretty vast. Some research finds that the usual pattern in science is constant rate of discovery from exponentially increasing number of researchers, suggesting strong low-hanging fruit effects, but these seem to be overwhelmed by other considerations in AI right now.

I think Eliezer’s position on this subject is shaped by assumptions like:

-

If you have an AI as intelligent as Elon Musk today, then tomorrow you can run it on more hardware with a bit of normal human algorithmic progress, and get one twice as intelligent. So even if it would take Elon years to make a breakthrough, long before those years are up you’ll have an AI that can make breakthroughs much faster.

-

An AI that’s twice as intelligence (or ten times as intelligent) as a human can actually make discoveries very quickly. I don’t know what kind of advantage Terry Tao (for the sake of argument, IQ 200) has over some IQ 190 mathematician, but his advantage over an IQ 100 mathematician is complete. In a world where mathematics had only ever been done by IQ 100 people, Tao could advance the art by centuries (of normal progress) in…Years? Days? Some very short amount of time.

-

Given that humans (in this scenario) were able to bring AI from SHRDLU to superintelligence in less than 100 years without gaining any IQ at all , presumably you can make lots and lots and lots of progress before hitting your IQ ceiling, by which point you have a new IQ ceiling.

I think this makes more sense than talking about criticality, or a change from 0.99 to 1.001.

What would Paul respond here? I think he’d say that even very stupid AIs can “contribute to AI research”, if you mean things like some AI researcher using Codex to program faster. So you could think of AI research as a production function involving both human labor and AI labor. As the quality of AI labor improves, you need less and less human labor to produce the same number of breakthroughs. At some point you will need zero human labor at all, but before that happens you will need 0.001 hours of human labor per breakthrough, and so this won’t make a huge difference.

Eliezer could respond in two ways. First, that the production function doesn’t look like that. There is no AI that can do 2/3 of the work in groundbreaking AI research; in order to do that, you need a fully general AI that can do all of it. This seems wrong to me; I bet there are labs where interns do a lot of the work but they still need the brilliant professor to solve some problems for them. That proves that there are intelligence levels where you can do 2/3, but not all, of AI research.

Or second, that AI will advance through these levels in hours or days. This doesn’t seem right to me either; the advent of Codex (probably) made AI research a little easier, but that doesn’t mean we’re only a few days from superintelligence. Paul gets to assume a gradual curve from Codex to whatever’s one level above Codex to whatever’s two levels . . . to superintelligence. Eliezer has to assume this terrain is full of gaps - you get something that helps a little, then a giant gap where increasing technology pays no returns at all, then superintelligence. This seems like a more specific prediction, the kind that requires some particular evidence in its favor which I don’t see.

Eliezer seems to really hate arguments like the one I just made:

This is just pumping hard again on the intuition that says incremental design changes yield smooth output changes, which (the meta-level of the essay informs us wordlessly) is such a strong default that we are entitled to believe it if we can do a good job of weakening the evidence and arguments against it.

And the argument is: Before there are systems great at self-improvement, there will be systems mediocre at self-improvement; implicitly: “before” implies “5 years before” not “5 days before”; implicitly: this will correspond to smooth changes in output between the two regimes even though that is not how continuous feedback loops work.

I guess I’m missing this argument. I see Paul as saying that “the loop” has already started with Codex (and more broadly with all human economic progress). It’s possible the speed might suddenly shift, like the gradually sloping plateau that suddenly ends in a huge cliff. But if you’ve been seeing nothing but gradually sloping plateau for the past thousand miles, the hypothesis “Just out of view there’s a huge cliff” requires more positive evidence than the hypothesis “Just out of view the plateau continues to slope at the same rate”.

Eliezer points out there have been some cliffs before. But supposing that in the past thousand miles, there have been three previous cliffs, “there is a huge cliff bigger than any you’ve ever seen just one mile beyond your sight” still seems to be non-default and require quite a bit of evidence.

The Actual Yudkowsky-Christiano Debate, Finally

All of this was just preliminaries, Eliezer and Paul taking potshots at each other from a distance. Someone finally got them together in the same [chat] room and forced them to talk directly.

It’s kind of disappointing. They spend most of the chat trying to figure out exactly where their ideas diverge. Paul thinks things will get pretty crazy before true superintelligence. Eliezer wants him to operationalize “pretty crazy” concretely enough that he can disagree.

They ended up focusing on a world where hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars are invested in AI (for context, this is about the value of the whole tech industry today). Partly this is because Paul thinks this sounds “pretty crazy” - it must mean that AI progress is exciting enough to attract lots of investors. But partly it’s because Eliezer keeps bringing up apparent examples of discontinuous progress - like AlphaGo - and Paul keeps dismissing them as “there wasn’t enough interest in AI to fill in the gaps that would have made that progress continuous”. If AI gets trillions in funding, he expects to see a lot fewer AlphaGos. Eliezer is mildly skeptical this world will happen, because he expects regulatory barriers to make it harder to deploy AI killer apps. But it doesn’t seem to be the crux of their disagreement.

The real problem is: both of them were on their best behavior, by which I mean boring. They both agreed they weren’t going to resolve this today, and that the most virtuous course would be to generate testable predictions on what the next five years would be like, in the hopes that one of their models would prove obviously much more productive at this task than the other.

But getting these predictions proved harder than expected. Paul believes “everything will grow at a nice steady rate” and Eliezer believes “everything will grow at a nice steady rate until we suddenly die”, and these worlds look the same until you are dead.

I am happy to report that three months later, the two of them finally found an empirical question they disagreed on and made a bet on it. The difference is: Eliezer thinks AI is a little bit more likely to win the International Mathematical Olympiad before 2025 than Paul (under a specific definition of “win”). I haven’t followed the many many comment sub-branches it would take to figure out how that connects to any of this, but if it happens, update a little towards Eliezer, I guess.

The Comments Section

Paul thinks AI will progress gradually; Eliezer suddenly. They differ not just in their future predictions, but their interpretation of past progress. For example, Eliezer sees the GPT series of writing AIs as appearing with surprising suddenness.

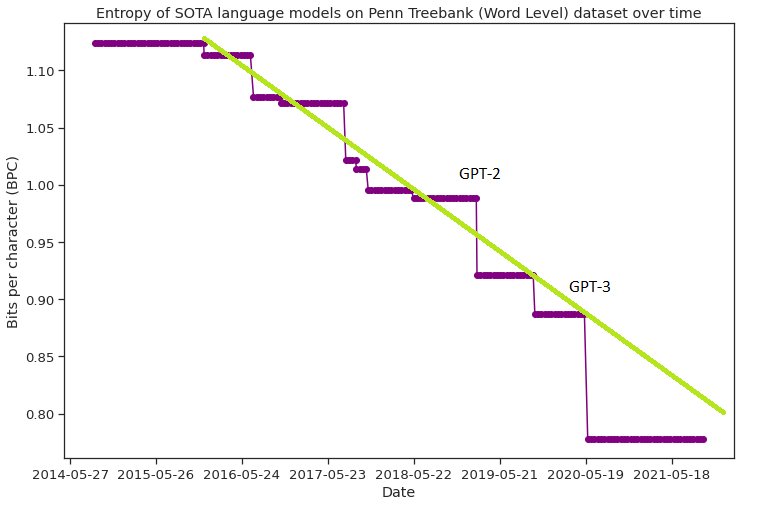

In the comments, Matthew Barnett points out that on something called Penn Treebank perplexity, a benchmark for measuring how good language models are, the GPTs mostly just continued the pre-existing trend:

Source: Matthew Barnett’s comment here, with pre-GPT trend line and announcement dates of GPTs drawn in.

Source: Matthew Barnett’s comment here, with pre-GPT trend line and announcement dates of GPTs drawn in.

Gwern answered (long comment, only partly cited):

The impact of GPT-3 had nothing whatsoever to do with its perplexity on Penn Treebank . . . the impact of GPT-3 was in establishing that trendlines did continue in a way that shocked pretty much everyone who’d written off ‘naive’ scaling strategies. Progress is made out of stacked sigmoids: if the next sigmoid doesn’t show up, progress doesn’t happen. Trends happen, until they stop. Trendlines are not caused by the laws of physics. You can dismiss AlphaGo by saying “oh, that just continues the trendline in ELO I just drew based on MCTS bots”, but the fact remains that MCTS progress had stagnated, and here we are in 2021, and pure MCTS approaches do not approach human champions, much less beat them. Appealing to trendlines is roughly as informative as “calories in calories out”; ‘the trend continued because the trend continued’. A new sigmoid being discovered is extremely important.

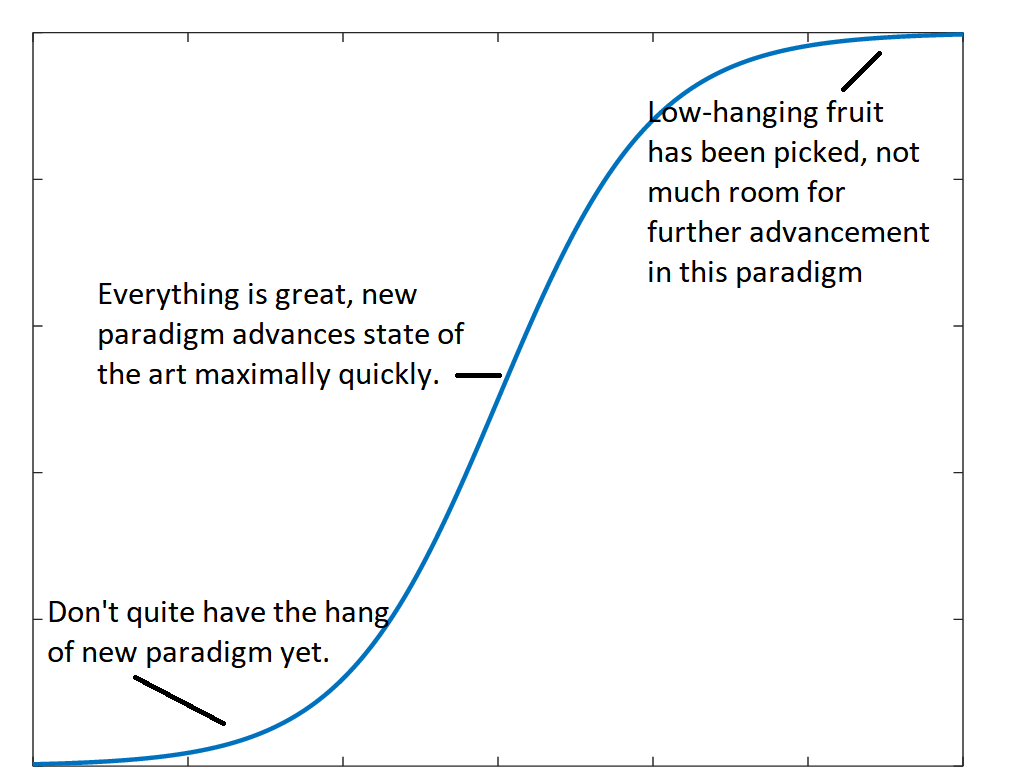

I’m not sure I fully understand this, but let me try. Progress tends to happen along sigmoid curves, one sigmoid per paradigm:

Consider cryptocurrency as an example. In 2010, cryptocurrency was small and hard to use. Its profits might have been growing quickly in relative terms, but slowly in absolute terms. But by 2020, it had become the next big thing. People were inventing new cryptocurrencies every day, technical challenges were falling one after another, lots of people were getting rich. And by 2030, presumably cryptocurrency will be where eg personal computers are now - still a big business, but most of the interesting work has been done, it’s growing at a boring normal growth rate, and improvements are rare and marginal.

Now imagine a graph of total tech industry profits over time. Without having seen this graph, I imagine relatively consistent growth. In the 1990s, the growth was mostly from selling PCs and Windows CDs, which were on the super-hot growth parts of their sigmoid. By the 2000s, those had matured and flattened out, but new paradigms (smartphones, online retail) were on the super-hot growth parts of their sigmoids. By the late 2010s, those had matured too, but newer paradigms (cryptocurrency, electric cars) were on the super-hot growth parts of their sigmoids. If we want to know what the next decade will bring, we should look for paradigms that are still in the early-slow-growth stage, maybe quantum computers. The idea is: each individual paradigm has a sigmoid that slows and peters out, but the tech industry as a whole generates new sigmoids and maintains its usual growth rate.

So if you look at eg the invention of Bitcoin, you could say “this is boring, it’s just causing tech industry profits to follow the normal predicted growth pattern after smartphones petered out, no need to update here.” Or you could say “actually this is a groundbreaking new invention that is making trillions of dollars, Satoshi is a genius, thank goodness he did this or else the tech industry would have crashed”.

One reason to prefer the second story is that tech industry profits probably won’t keep going up continuously forever. Global population kept going up at a fixed rate for tens of thousands of years, then stopped in 1960 (it had to stop sometime or we would have had infinite people in 2026). US GDP goes up at a pretty constant rate, but I assume Roman GDP did too, before it stopped and reversed. So when Satoshi invents Bitcoin and it becomes the hot new thing, even though it only continues the trend, you’ve learned important new information: namely, that the trend does continue, at least for one more cycle.

So here it looks like Matthew is taking the reductionist perspective (that the GPTs were just a predictable continuation of trend) and Gwern is taking the more interesting perspective (the trend continuing is exciting and important).

While I acknowledge Gwern has a good point here, it seems - not entirely related to the point under discussion? Yes, progress will come from specific people doing specific things, and they deserve to be celebrated, but Paul’s position - that progress is gradual and predictable - still stands.

But then Gwern makes another more fundamental objection:

GPT-3 further showed completely unpredicted emergence of capabilities across downstream tasks which are not measured in PTB perplexity. There is nothing obvious about a PTB BPC of 0.80 that causes it to be useful where 0.90 is largely useless and 0.95 is a laughable toy. (OAers may have had faith in scaling, but they could not have told you in 2015 that interesting behavior would start at 𝒪(1b), and it’d get really cool at 𝒪(100b).) That’s why it’s such a useless metric. There’s only one thing that a PTB perplexity can tell you, under the pretraining paradigm: when you have reached human AGI level. (Which is useless for obvious reasons: much like saying that “if you hear the revolver click, the bullet wasn’t in that chamber and it was safe”. Surely true, but a bit late.) It tells you nothing about intermediate levels. I’m reminded of the Steven Kaas line: “Why idly theorize when you can JUST CHECK and find out the ACTUAL ANSWER to a superficially similar-sounding question SCIENTIFICALLY?”

In other words, suppose AIs start at Penn Treebank perplexity 100 and go down by one every year. After 20 years, they have PTP 80 and are useless. After 21 years, they have PTP 79 and are suddenly strong enough to take over the world. Was their capability gain gradual or sudden? It was gradual in PTP, but sudden in real-life abilities we care about.

Eliezer comments:

What does it even mean to be a gradualist about any of the important questions like [the ones Gwern mentions], when they don’t relate in known ways to the trend lines that are smooth? Isn’t this sort of a shell game where our surface capabilities do weird jumpy things, we can point to some trend lines that were nonetheless smooth, and then the shells are swapped and we’re told to expect gradualist AGI surface stuff? This is part of the idea that I’m referring to when I say that, even as the world ends, maybe there’ll be a bunch of smooth trendlines underneath it that somebody could look back and point out. (Which you could in fact have used to predict all the key jumpy surface thresholds, if you’d watched it all happen on a few other planets and had any idea of where jumpy surface events were located on the smooth trendlines - but we haven’t watched it happen on other planets so the trends don’t tell us much we want to know.)

That is: when will an AI achieve Penn Treebank perplexity of 0.62? Based on the green line on the graph above, probably sometime around 2027. When will it be able to invent superweapons? Nobody has any idea. So who cares?

Paul:

This seems totally bogus to me.

It feels to me like you mostly don’t have views about the actual impact of AI as measured by jobs that it does or the $s people pay for them, or performance on any benchmarks that we are currently measuring, while I’m saying I’m totally happy to use gradualist metrics to predict any of those things. If you want to say “what does it mean to be a gradualist” I can just give you predictions on them.

To you this seems reasonable, because e.g. $ and benchmarks are not the right way to measure the kinds of impacts we care about. That’s fine, you can propose something other than $ or measurable benchmarks. If you can’t propose anything, I’m skeptical.

In other words, if Eliezer doesn’t care about boring things like Penn Treebank, then he should talk about interesting things, and Paul will predict AI will be gradual in those too. Number of jobs cost/year? Amount of money produced by the AI industry? Destructiveness of the worst superweapon invented by AI? (did you hear that an AI asked to invent superweapons recently reinvented VX nerve gas after only six hours’ computation?)

Eliezer has already talked about why he doesn’t expect abstracted AI progress to show immediate results in terms of jobs, etc, and Paul knows this. I think Paul is trying to use a kind of argument from incredulity that AI genuinely wouldn’t have any meaningful effects that can be traced in a gradual pattern.

And The Winner Is…

…Paul absolutely, Eliezer directionally.

This is the Metaculus forecasting question corresponding to Paul’s preferred formulation of hard/soft takeoff. Metaculans think there’s a 69% chance it’s true. But it fell by about 4% after the debate, suggesting that some people got won over to Eliezer’s point of view.

Rafael Harth tried to get the same information with a simple survey, and got similar results: on a scale of 1 (strongly Paul) to 9 (strongly Eliezer), the median moved from a 5 to a 7.

Should this make us more concerned? Less concerned? I’ll give the last word to Raemon, who argues that both scenarios are concerning for different reasons:

I totally think there are people who sort of nod along with Paul, using it as an excuse to believe in a rosier world where things are more comprehensible and they can imagine themselves doing useful things without having a plan for solving the actual hard problems. Those types of people exist. I think there’s some important work to be done in confronting them with the hard problem at hand.

But, also… Paul’s world AFAICT isn’t actually rosier. It’s potentially more frightening to me. In Smooth Takeoff world, you can’t carefully plan your pivotal act with an assumption that the strategic landscape will remain roughly the same by the time you’re able to execute on it. Surprising partial-gameboard-changing things could happen that affect what sort of actions are tractable. Also, dumb, boring ML systems run amok could kill everyone before we even get to the part where recursive self improving consequentialists eradicate everyone.

I think there is still something seductive about this world – dumb, boring ML systems run amok feels like the sort of problem that is easier to reason about and maybe solve. (I don’t think it’s actually necessarily easier to solve, but I think it can feel that way, whether it’s easier or not). And if you solve ML-run-amok-problems, you still end up dead from recursive-self-improving-consequentialists if you didn’t have a plan for them.

As usual, I think the takeaway is “everyone is uncertain enough on this point that it’s worth being prepared for either scenario. Also, we are bottlenecked mostly by ideas and less by other resources, so if anyone has ideas for dealing with either scenario we should carry them out, while worrying about the relative likelihood of each only in the few cases where there are real tradeoffs.”