Contra Stone On EA

I.

Lyman Stone wrote an article Why Effective Altruism Is Bad. You know the story by now, let’s start with the first argument:

The only cities where searches for EA-related terms are prevalent enough for Google to show it are in the Bay Area and Boston…We know the spatial distribution of effective altruist ideas. We can also get IRS data on charitable giving…

Stone finds that Google Trends shows that searches for “effective altruism” concentrate most in the San Francisco Bay Area and Boston. So he’s going to see if those two cities have higher charitable giving than average, and use that as his metric of whether EAs give more to charity than other people.

He finds that SF and Boston do give more to charity than average, but not by much, and this trend has if anything decreased in the 2010 - present period when effective altruism was active. So, he concludes,

That should all make us think that the rise of ‘effective altruism’ as a social movement has had little or no effect on overall charitableness.

What do I think of this line of argument?

According to Rethink Priorities, the organization that keeps track of this kind of thing, there were about 7,400 active effective altruists in 2020 (90% CI: 4,700 - 10,000). Growth rate was 14% per year but has probably gone down lately, so there are probably around 10,000 now. This matches other sources for high engagement with EA ideas (8,898 people have signed the Giving What We Can pledge).

Suppose that the Bay Area contains 25% of all the effective altruists in the world. That means it has 2,500 effective altruists. Its total population is about 10 million. So effective altruists are 1/4000th of the Bay Area population.

Suppose that the average person gives 3% of their income to charity per year, and the average effective altruist gives 10%. The Bay Area with no effective altruists donates an average of 3%. Add in the 2,500 effective altruists, and the average goes up to . . . 3.0025%. Stone’s graph is in 0.5 pp intervals. So this methodology is way too underpowered to detect any effect even if it existed.

How many effective altruists would have to be in the Bay for Stone to notice? If we assume ability to detect a signal of 0.5 pp, it would take 200x this amount, or 500,000 in the Bay alone. For comparison, the most popular book on effective altruism, Will MacAskill’s What We Owe The Future, sold only 100,000 copies in the whole world.

But all of this speculation is unnecessary. There are plenty of data sources that just tell us how much effective altruists donate compared to everyone else. I checked this in an old SSC survey, and the non-EAs (n = 3118) donated an average of 1.5%, compared to the EA (n = 773) donating an average of 6%.

In general, I think it’s a bad idea to try to evaluate rare events by escalating to a population level when you can just check the rare events directly. If you do look at populations, you should do a basic power calculation before reporting your results as meaningful.

I’m not going to make a big deal about Stone’s use of Google Trends, because I think he’s right that SF and Boston are the most EA cities. But taken seriously, it would suggest that Montana is the most Democratic state.

I’m not going to make a big deal about Stone’s use of Google Trends, because I think he’s right that SF and Boston are the most EA cities. But taken seriously, it would suggest that Montana is the most Democratic state.

Stone could potentially still object that movements aren’t supposed to gather 10,000 committed adherents and grow at 10% per year. They have to take hold of the population! Capture the minds of the masses! Convert >5% of the population of a major metropolitan area!

I don’t think effective altruism has succeeded as a mass movement. But I don’t think that’s it’s main strategy - for more on this, see the articles under EA Forum tag “value of movement growth”, which explains:

It may seem that, in order for the effective altruism movement to do as much good as possible, the movement should aim to grow as much as possible. However, there are risks to rapid growth that may be avoidable if we aim to grow more slowly and deliberately. For example, rapid growth could lead to a large influx of people with specific interests/priorities who slowly reorient the entire movement to focus on those interests/priorities.

Aren’t movements that don’t capture the population doomed to irrelevance? I don’t think so. Effective altruism has managed to get plenty done with only 10,000 people, because they’re the right 10,000 and they’ve influenced plenty of others.

Stone fails to prove that effective altruists don’t donate more than other people, because he’s used bad methodology that couldn’t prove that even if it were true. His critique could potentially evolve into an argument that effective altruism hasn’t spread massively throughout the population, but nobody ever claimed that it did.

II.

You might imagine that a group fixated on “effective altruism” would have a high degree of concentration of giving in a small number of areas. Indeed, EAist groups tend to be hyper-focused on one or two causes, and even big groups like Open Philanthropy or GiveWell often have focus areas of especially intense work.

And yet, the list of causes EAists work on is shockingly broad for a group whose whole appeal is supposed to be re-allocating funds towards their most effective uses. Again, click the link I attached above.

EAists do everything from supporting malarian bednets (seems cool), to preventing blindness-related conditions (makes sense), to distributing vaccines (okay, I’m following), to developing vaccines in partnership with for profit entities (a bit more oblique but I see where you’re going with it), to institutional/policy interventions (contestable, but there’s a philosophical case I guess), to educational programs in rich countries (sympathetic I guess but hardly the Singer-esque “save the cheapest life” vibe), to promoting kidney transplants (noble to be sure but a huge personal cost for what seems like a modest total number of utils gained), to programs to reduce the pain experienced by shrimp in agriculture (seems… uh… oblique), to lobbying efforts to prevent AI from killing us all (lol), to space flight (what?), to more nebulous “long term risk” (i.e. “pay for PhDs to write white papers”), to other even more alternatively commendable, curious, or crazy causes. My point is not to mock the sillier programs (I’ll do that later). My point is just to question on what basis so broad a range of priorities can reasonably be considered a major gain in efficiency. Is it really the case that EAists have radically shifted our public understandings of the “effectiveness” of certain kinds of “altruism”?

A few responses:

Technically, it’s only correct to focus on the single most important area if you have a small amount of resources relative to the total amount in the system (Open Phil has $10 billion). Otherwise, you should (for example) spend your first million funding all good shrimp welfare programs until the marginal unfunded shrimp welfare program is worse than the best vaccine program. Then you’ll fund the best vaccine program, and maybe they can absorb another $10 million until they become less valuable than the marginal kidney transplant or whatever. This sounds theoretical when I put it this way, but if you’ve ever worked in charity it quickly becomes your whole life. It’s all very nice and well to say “fund kidney transplants”, but actually there are only specific discrete kidney transplant programs, some of them are vastly better than others, and none of them scale to infinity instantaneously or smoothly. The average amount that the charities I deal with most often can absorb is between $100K and $1MM. Again, Open Phil has $10 billion.

But even aside from this technical point, people disagree on really big issues. Some people think animals matter and deserve the same rights as humans. Other people don’t care about them at all. Effective altruism can’t and doesn’t claim to resolve every single ancient philosophical dispute on animal sentience or the nature of rights. It just tries to evaluate if charities are good. If you care a lot about shrimp, there’s someone at some effective altruist organization who has a strong opinion on exactly which shrimp-related charity saves shrimp most cost-effectively. But nobody (except philosophers, or whatever) can tell you whether to care about shrimp or not.

This is sort of a cop-out. Effective altruism does try to get beyond “I want to donate to my local college’s sports team”. I think this is because that’s an easy question. Usually if somebody says they want to donate there, you can ask “do you really think your local college’s sports team is more important than people starving to death in Sudan?” and they’ll think for a second and say “I guess not”. Whereas if you ask the same question about humans and animals, you’ll get all kinds of answers and no amount of short prompting can solve this disagreement. I think this puts EAs in a few basins of reflective equilibrium, compared to scattered across the map.

So is there some sense, as Stone suggests, that “so broad a range of priorities [can’t] reasonably be considered a major gain in efficiency”?

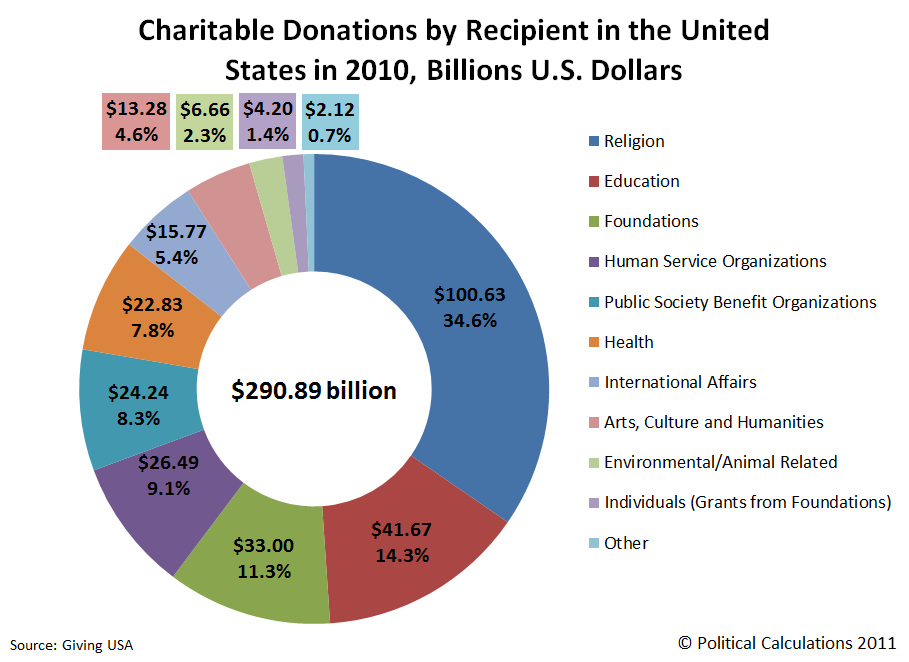

I think if you look at donations by the set of non-effective-altruist donors, and the set of effective-altruist donors, there will be much much more variance, and different types of variance, in the non-EAs than the EAs. Here’s where most US charity money goes (source):

Try spotting existential risk prevention on here.

Try spotting existential risk prevention on here.

I don’t think Stone can claim that an EA version of this chart wouldn’t look phenomenally different. But then what’s left of his argument?

III.

Effective altruists devote absolutely enormous amounts of mental energy and research costs to program assessment, measurement of effectiveness. Those studies yield usually-conflicting results with variable effect sizes across time horizons and model specifications, and tons of different programs end up with overlapping effect estimates. That is to say, the areas where EAist style program evaluations are most compelling are areas where we don’t need them: it’s been obvious for a long time how to reduce malaria deaths, program evaluations on that front have been encouraging and marginally useful, but not gamechanging. On the other hand, in more contestable areas, EAist style program evaluations don’t really yield much clarity. It’s very rare that a program evaluation gets published finding vastly larger benefits than you’d guess from simple back-of-the-envelope guesswork, and the smaller estimates are usually because a specific intervention had first-order failure or long-run tapering, not because “actually tuberculosis isn’t that bad” or something like that. Those kinds of precise program-delivery studies are actually not an EAist specialty, but more IPA’s specialty.

My second critique, then is this: there is no evidence that the toolkit and philosophical approach EAists so loudly proclaim as morally superior actually yields any clarity, or that their involvement in global efforts is net-positive vs. similar-scale donations given through near-peer organizations.

The IPA mentioned here is Innovations For Poverty Action, a group that studies how to fight poverty. They’re great and do great work.

But IPA doesn’t recommend top charities or direct donations. Go to their website, try to find their recommended charities. There are none. GiveWell does have recommended charities - including ones that they decided to recommend based on IPA’s work - and moves ~$250 million per year to them. If IPA existed, but not GiveWell, the average donor wouldn’t know where to donate, and ~$250 million per year would fail to go to charities that IPA likes.

I think from the perspective of people who actually work within this ecosystem, Stone’s concern is like saying “Farms have already solved the making-food problem, so why do we need grocery stores?”

(also, effective altruism funds IPA)

I’m focusing on IPA here because Stone brought them up, but I think EA does more than this. I don’t think there’s an IPA for figuring out whether asteroid deflection is more cost-effective than biosecurity, whether cow welfare is more effective than chicken welfare, or figuring out which AI safety institute to donate to. I think this is because IPA is working on a really specific problem (which kinds of poverty-related interventions work) and EA is working on a different problem (what charities should vaguely utilitarian-minded people donate to?) These are closely related questions but they’re not the same question - which is why, for example, IPA does (great) research into consumer protection, something EA doesn’t consider comparatively high-impact.

And I’m still focusing on donation to charity, again because it’s what Stone brought up, but EA does other things - like incubating charities, or building networks that affect policy.

IV.

Let’s skip farm animal welfare for a second and look at the next few: Global Aid, “Effective Altruism,” potential AI risks, biosecurity, and global catastrophic risk. These are all definitely disproportionate areas of EAist interest. If you google these topics, you will find a wildly disproportionate number of people who are EAist, or have sex at EAist orgies, or are the friends of people who have sex at EAist orgies. These really are some of the unique social features of EAism.

And they largely amount to subsidizing white collar worker wages. I’m sorry but there’s no other way to slice it: these are all jobs largely aimed at giving money to researchers, PhD-holders, university-adjacent-persons, think tanks, etc. That may be fine stuff, but the whole pitch of effective altruism is that it’s supposed to bypass a lot of the conventional nonprofit bureaucracy and its parasitism and just give money to effective charities. But as EAism as matured into a truly unique social movement, it is creating its own bureaucracy of researchers, think tanks, bureaucrats… the very things it critiqued.

Suppose an EA organization funded a cancer researcher to study some new drug, and that new drug was a perfect universal cure for cancer. Would Stone reject this donation as somehow impure, because it went to a cancer researcher (a white-collar PhD holder)?

EA gives hundreds of millions of dollars directly to malaria treatments that go to the poorest people in the world. It’s also one the main funders of GiveDirectly, a charity that has given money ($750 million so far) directly to the poorest people in the world. But in addition to giving out bednets directly, it sometimes funds malaria vaccines. In addition to giving to poor Africans, it also funds the people who do the studies to see whether giving to poor Africans works. Some of those are white-collar workers.

EA has never been about critiquing the existence of researchers and think tanks. In fact, this is part of the story of EA’s founding. In 2007, the only charity evaluators accessible by normal people rated charities entirely on how much overhead they had - whether the money went to white-collar people or to sympathetic poor recipients. EAs weren’t the first to point out that this was a very weak way of evaluating charities. But they were the first to make the argument at scale and bring it into the public consciousness, and GiveWell (and to some degree the greater EA movement) were founded on the principle of “what if there was a charity evaluator that did better than just calculate overhead?” In accordance with this history, if you look on Giving What We Can’s List Of Misconceptions About Effective Altruism, their #1 Misconception about about charity evaluation is that “looking at a charity’s overhead costs is key to evaluating its effectiveness”.

This is another part of my argument that EA is more than just IPA++. For years, the state of the art for charity evaluators was “grade them by how much overhead they had”. IPA and all the great people working on evidence-based charity at the time didn’t solve that problem - people either used CharityNavigator or did their own research. GiveWell did solve that problem, and that success sparked a broader movement to come up with a philosophy of charity that could solve more problems. Many individuals have always had good philosophies of charity, but I think EA was a step change in doing it at scale and trying to build useful tools / a community around it.

V.

You could of course say AI risk is a super big issue. I’m open to that! But surely the solution to AI risk is to invest in some drone-delivered bombs and geospatial data on computing centers! The idea that the primary solution here is going to be blog posts, white papers, podcasts, and even lobbying is just insane. If you are serious about ruinous AI risk, you cannot possibly tell me that the strategy pursued here is optimal vs. say waiting until a time when workers have all gone home and blowing up a bunch of data centers and corporate offices. In particular terrorism as a strategy may be efficient since explosives are rather cheap. To be clear I do not support a strategy of terrorism!!!! But I am questioning why AI-riskers don’t. Logically, they should.

I think if you have to write in bold with four exclamation points at the end that you’re not explicitly advocating terrorism, you should step back and think about your assumptions further. So:

Should people who worry about global warming bomb coal plants?

Should people who worry that Trump is going to destroy American democracy bomb the Republican National Convention?

Should people who worry about fertility collapse and underpopulation bomb abortion clinics?

EAs aren’t the only group who think there are deeply important causes. But for some reason people who can think about other problems in Near Mode go crazy when they start thinking about EA.

(Eliezer Yudkowsky has sometimes been accused of wanting to bomb data centers, but he supports international regulations backed by military force - his model is things like Israel bombing Iraq’s nuclear program in the context of global norms limiting nuclear proliferation - not lone wolves. As far as I know, all EAs are united against this kind of thing.)

There are three reasons not to bomb coal plants/data centers/etc. The first is that bombing things is morally wrong. I take this one pretty seriously.

The second is that terrorism doesn’t work. Imagine that someone actually tried to bomb a data center. First of all, I don’t have statistics but I assume 99% of terrorists get caught at the “your collaborator is an undercover fed” stage. Another 99% get eliminated at the “blown up by poor bomb hygiene and/or a spam text message” stage. And okay, 1/10,000 will destroy a datacenter, and then what? Google tells me there are 10,978 data centers in the world. After one successful attack, the other 10,977 will get better security. Probably many of these are in China or some other country that’s not trivial for an American to import high explosives into.

The third is that - did I say terrorism didn’t work? I mean it massively massively backfires. Hamas tried terrorism, they frankly did a much better job than we would, and now 52% of the buildings in their entire country have been turned to rubble. Osama bin Laden tried terrorism, also did an impressive job, and the US took over the whole country that had supported him, then took over an unrelated country that seemed like the kinds of guys who might support him, then spent ten years hunting him down and killing him and everyone he had ever associated with.

One f@#king time , a handful of EAs tried promoting their agenda by committing some crimes which were much less bad than terrorism. Along with all the direct suffering they caused, they destroyed EA’s reputation and political influence, drove thousands of people away from the movement, and everything they did remains a giant pit of shame that we’re still in the process of trying to climb our way out of.

Not to bang the same drum again and again, but this is why EA needs to be a coherent philosophy and not just IPA++. You need some kind of theory of what kinds of activism are acceptable and effective, or else people will come up with morally repugnant and incredibly idiotic plans that will definitely backfire and destroy everything you thought you were fighting for.

EA hasn’t always been the best at avoiding this failure mode, but at least we manage to outdo our critics.

VI.

Stone moves on to animal welfare:

It’s important to grasp that [caring about animals] is, in evolutionary terms, an error in our programming. The mechanisms involved are entirely about intra-human dynamics (or, some argue, may also be about recognizing the signs of vulnerable prey animals or enabling better hunting). Yes humans have had domestic animals for quite a long time, but our sympathetic responses are far older than that. We developed accidental sympathies for animals and then we made friends with dogs, not vice versa.

Again, this is part of why I think it’s useful to have people who think about philosophy, and not just people who do RCTs.

People having kids of their own instead of donating to sperm banks is in some sense an “error” in our evolutionary program. The program just wanted us to reproduce; instead we got a bunch of weird proxy goals like “actually loving kids for their own sake”.

Art is another error - I assume we were evolutionarily programmed to care about beauty because, I don’t know, flowers indicate good hunting grounds or something, not because evolution wanted us to paint beautiful pictures.

Anyone who cares about a future they will never experience, or about people on far off continents who they’ll never meet, is in some sense succumbing to “errors” in their evolutionary programming. Stone describes the original mechanisms as “about intra-human dynamics”, but this is cope - they’re about intra-tribal dynamics. Plenty of cultures have been completely happy to enslave, kill, and murder people outside their tribes, and nothing in their evolutionary mechanism has told them not to. Does Stone think this, too, is an error?

At some point you’ve got to go beyond evolutionary programming and decide what kind of person you want to be. I want to be the kind of person who cares about my family, about beauty, about people on other continents, and - yes - about animal suffering. This is the reflective equilibrium I’ve landed in after considering all the drives and desires within me, filtering it through my ability to use Reason, and imagining having to justify myself to whatever God may or may not exist.

Stone suggests EAs don’t have answers to a lot of the basic questions around this. I can recommend him various posts like Axiology, Morality, Law, the super-old Consequentialism FAQ, and The Gift We Give To Tomorrow, but I think they’ll only address about half of his questions. The other half of the answers have to come from intuition, common sense, and moral conservatism. This isn’t embarrassing. Logicians have discovered many fine and helpful logical principles, but can’t 100% answer the problem of skepticism - you can fill in some of the internal links in the chain, but the beginning and end stay shrouded in mystery. This doesn’t mean you can ignore the logical principles we do know. It just means that life is a combination of formally-reasonable and not-formally-reasonable bits. You should follow the formal reason where you have it, and not freak out and collapse into Cartesian doubt where you don’t. This is how I think of morality too.

Again, I really think it’s important to have a philosophy and not just a big pile of RCTs. Our critics make this point better than I ever could. They start with “all this stuff is just common sense, who needs philosophy, the RCTs basically interpret themselves”, then, in the same essay, digress into:

-

If I wanted to do this stuff, I would try terrorism.

-

Don’t donate to research, policy, or anything else where people have PhDs.

-

Cruelty to animals is okay, because of evolution.

Morality is tough. Converting RCTs - let alone the wide world of things we don’t have RCTs on yet - into actionable suggestions is tough. Many people have tried this. Some have succeeded very well on their own. Effective altruism is a community of people working on this problem together. I’m grateful to have it.

VII.

Stone’s final complaint:

Where Bentham’s Bulldog is correct is a lot of the critique of EAists is personal digs.

This is because EAism as a movement is full of people who didn’t do the reading before class, showed up, had a thought they thought was original, wrote a paper explaining their grand new idea, then got upset a journal didn’t publish it on the grounds that, like, Aristotle thought of it 2,500 years ago. The other kids in class tend to dislike the kid who thinks he’s smarter than them, especially if, as it happens, he is not only not smarter, he is astronomically less reflective…Admit you’re not special and you’re muddling through like everybody else, and then we can be friends again.

I’ll be excessively cute here: Stone is repeating one of the most common critiques of EA as if it’s his own invention, without checking the long literature of people discussing it and coming up with responses to it. I’m tired enough of this that I’m just going to quote some of what I said the last time I wrote about this argument:

1: It’s actually very easy to define effective altruism in a way that separates it from universally-held beliefs.

For example (warning: I’m just mouthing off here, not citing some universally-recognized Constitution EA Of Principles):

1. Aim to donate some fixed and considered amount of your income (traditionally 10%) to charity, or get a job in a charitable field.

2. Think really hard about what charities are most important, using something like consequentialist reasoning (where eg donating to a fancy college endowment seems less good than saving the lives of starving children). Treat this problem with the level of seriousness that people use when they really care about something, like a hedge fundie deciding what stocks to buy, or a basketball coach making a draft pick. Preferably do some napkin math, just like the hedge fundie and basketball coach would. Check with other people to see if your assessments agree.

3. ACTUALLY DO THESE THINGS! DON’T JUST WRITE ESSAYS SAYING THEY’RE “OBVIOUS” BUT THEN NOT DO THEM!

I think less than a tenth of people do (1), less than a tenth of those people do (2), and less than a tenth of people who would hypothetically endorse both of those get to (3). I think most of the people who do all three of these would self-identify as effective altruists (maybe adjusted for EA being too small to fully capture any demographic?) and most of the people who don’t, wouldn’t.

Step 2 is the interesting one. It might not fully capture what I mean: if someone tries to do the math, but values all foreigners’ lives at zero, maybe that’s so wide a gulf that they don’t belong in the same group. But otherwise I’m pretty ecumenical about “as long as you’re trying” […]

2: Part of the role of EA is as a social technology for getting you to do the thing that everyone says they want to do in principle.

I talk a big talk about donating to charity. But I probably wouldn’t do it much if I hadn’t taken the Giving What We Can pledge (a vow to give 10% of your income per year) all those years ago. It never feels like the right time. There’s always something else I need the money for. Sometimes I get unexpected windfalls, donate them to charity while expecting to also make my usual end of year donation, and then - having fulfilled the letter of my pledge - come up with an excuse not to make my usual end-of-year donation too.

Cause evaluation works the same way. Every year, I feel bad free-riding off GiveWell. I tell myself I’m going to really look into charities, find the niche underexplored ones that are neglected even by other EAs. Every year (except when I announce ACX Grants and can’t get out of it), I remember on December 27th that I haven’t done any of that yet, grumble, and give to whoever GiveWell puts first (or sometimes EA Funds).

And I’m a terrible vegetarian. If there’s meat in front of me, I’ll eat it. Luckily I’ve cultivated an EA friend group full of vegetarians and pescetarians, and they usually don’t place meat in front of me. My friends will cook me delicious Swedish meatballs made with Impossible Burger, or tell me where to find the best fake turkey for Thanksgiving (it’s Quorn Meatless Roast). And the Good Food Institute (an EA-supported charity) helps ensure I get ever tastier fake meat every year.

Everyone says they want to be a good person and donate to charity and do the right thing. EAs say this too. But nobody stumbles into it by accident. You have to seek out the social technology, then use it.

I think this is the role of the wider community - as a sort of Alcoholics Anonymous, giving people a structure that makes doing the right thing easier than not doing it. Lots of alcoholics want to quit in principle, but only some join AA. I think there’s a similar level of difference between someone who vaguely endorses the idea of giving to charity, and someone who commits to a particular toolbox of social technology to make it happen.

(I admit other groups have their own toolboxes of social technology to encourage doing good, including religions and political groups. Any group with any toolbox has earned the right to call themselves meaningfully distinct from the masses of vague-endorsers).

You can find the rest of the post here. I’ve also addressed similar questions at In Continued Defense of Effective Altruism and Effective Altruism As A Tower Of Assumptions.