Dictator Book Club: Chavez

[previously in series:Erdogan, Modi, Orban, Xi, Putin]

I.

All dictators get their start by discovering some loophole in the democratic process. Xi realized that control of corruption investigations let him imprison anyone he wanted. Erdogan realized that EU accession talks provided the perfect cover to retool Turkish institutions in his own image.

Hugo Chavez realized that there’s no technical limit on how often you can invoke the emergency broadcast system. You can do it every day! The “emergency” can be that you had a cool new thought about the true meaning of socialism. Or that you’re opening a new hospital and it makes a good photo op. Or that opposition media is saying something mean about you, and you’d like to prevent anyone from watching that particular channel (which is conveniently bound by law to air emergency broadcasts whenever they occur).

This might not be the only reason or even the main reason Hugo Chavez ended up as dictator. But it’s a very representative reason. If Putin is basically a spook and Modi is basically an ascetic, Hugo Chavez was basically a showman. He could keep everyone’s attention on him all the time (the emergency broadcast system didn’t hurt). And once their attention was on him, he could delight them, enrage them, or at least keep them engaged. And he never stopped. Hugo Chavez was the marathon runner of dictators.

He was on television almost every day for hours at a time, invariably live, with no script or teleprompter, mulling, musing, deciding, ordering. His word was de facto law, and he specialised in unpredictable announcements: nationalisations, referenda, troop mobilizations, cabinet shuffles. You watched not just for news value. The man was a consummate performer. He would sing, dance, rap; ride a horse, a tank, a bicycle; aim a rifle, cradle a child, scowl, blow kisses; act the fool, the statesman, the patriarch. There was a freewheeling, improvised air to it all. Suspense came from not knowing what would happen.

There would be no warning. Soap operas, films, and baseball games would dissolve and be replaced by the familiar face seated behind a desk or maybe the wheel of a tractor . . . it could [last] minutes or hours. Sometimes Chavez wouldn’t be talking, merely attending a ceremony . . . One time Chavez decided to personally operate a machine on the Caracas-to-Charallave rail tunnel. A television and radio announcer improvised commentary for the first few minutes, but gradually ran out of things to say as the president continued drilling, drilling, drilling. Radio listeners, blind to Chavez pounding away, were baffled and then alarmed by the mechanical roar monopolizing the airwaves. Some thought it signaled a coup.

In 2012, while he was dying of cancer, Chavez gave “a state of the nation address lasting nine and a half hours. A record. No break, no pause.” Put a TV camera in front of him, and the man was a machine.

If he had been an ordinary celebrity, he would be remembered as a legend. But he went too far. He became his TV show. He optimized national policy for ratings. The book goes into detail on one broadcast in particular, where he was filmed walking down Venezuela’s central square, talking to friends. He remarked on how the square needed more monuments to glorious heroes. But where could he put them? The camera shifted to a mall selling luxury goods. A lightbulb went on over the dictator’s head: they could expropriate the property of the rich capitalist elites who owned the mall, and build the monument there. Make it so! Had this been planned, or was it really a momentary whim? Nobody knew.

Then he would move on to some other topic. An ordinary citizen would call in and describe a problem. Chavez would be outraged, and immediately declare a law which solved that problem in the most extreme possible way. Was this staged? Was it a law he had been considering anyway? Again, hard to tell.

Sometimes everyone in government would ignore his decisions to see if he forgot about them. Sometimes he did. Other times he didn’t, and would demand they be implemented immediately. Nobody ever had a followup plan. They expropriated the mall, but Chavez’s train of thought had already moved on, and nobody had budgeted for the glorious monuments he had promised. The mall sat empty; it became a dilapidated eyesore. Laws declared on the spur of the moment to sound maximally sympathetic to one person’s specific problem do not, when combined into a legal system, form a great basis for governing a country.

But Chavez TV was also a game show. The contestants were government ministers. The prize was not getting fired. Offenses included speaking out against Chavez:

Chavez clashed with and fired all his ministers at one time or another but forgave and reinstated his favorites. Nine finance ministers fell in succession . . . it was palace custom not to give reasons for axing. Chavez, or his private secretary, would phone the marked one to say thank you but your services are no longer required. Good-bye. The victim was left guessing. Did someone whisper to the comandante? Who? Richard Canan, a young, rising commerce minister, was fired after telling an internal party meeting that the government was not building enough houses. Ramon Carrizales was fired as vice president after privately complaining about Cuban influence. Whatever the cause, once the axe fell, expulsion was immediate. The shock was disorienting. Ministers who used to bark commands and barge through doors seemed to physically shrink after being ousted . . . they haunted former colleagues at their homes, seeking advice and solace, petitioning for a way back to the palace. ‘Amigo, can you have a word with the chief?’ One minister, one of Chavez’s favorites, laughed when he recounted this pitiful lobbying. “They know it as well as I do. In [this government] there are no amigos.”

…or taking any independent action:

[A minister] was not supposed to suggest an initiative, solve a problem, announce good news, theorise about the revolution, or express an original opinion. These were tasks for the comandante. His fickleness encouraged ministers to defer implementation until they were certain of his wishes. In any case they spent so much time on stages applauding - it was unwise to skip protocol events - that there was little opportunity for initiative. Thus the oil minister Rafael Ramirez would lurk, barely visible, while the comandante signed a lucrative deal with Chevron […]

But upon command, the stone would transform into a whirling dervish . . . the comandante’s impulsiveness demanded instant, urgent responses. He would become consumed by a theme. Rice! Increase rice production! The order would ricochet through [the government]. The agriculture, planning, transport, commerce, finance, and infrastructure ministers would work around the clock devising a scheme or credits, loans, cooperatives, mills and trucks to have it ready, at least on paper, for the comandante to unveil on his Sunday show. Thus was born the Mixed Company for Socialist Rice. Then, the next week, chicken! Cheaper chicken! The same ministers would forget about rice while they rushed to squeeze farmers, truckers, and supermarkets sot hat the comandante could say, on his next show, that chicken was cheaper.

…or, worst of all, not enjoying Chavez’s TV shows enough:

[Ministers had to] arrange their features into appropriate expressions when on camera or in the comandante’s sight line. This was tricky when the comandante did something foolish or bizarre because the required response could contradict instinct… Missing a cue could be fatal. During a show the comandante’s laser-beam gaze swung from face to face, spotlighting expressions, seeking telltale tics. Immediately after a broadcast, Chavez reviewed the footage, casting a professional eye over the staging, lighting, camera angles - and audience reaction.

The comandante’s occasional lapses into ridiculous were inevitable. He spoke up to nine hours at a time live on television, without a script . . . Being capricious and clownish also sustained interest in the show and underlined his authority. No other government figure, after all, dared show humour in public. But on occasion this dissolved into absurdity. Who tells a king he is being a fool?

Ministers faced another test of the mask in September 2007, when the comandante announced clocks would go back half an hour. The aim was to let children and workers wake up in daylight, he said. “I don’t care if they call me crazy, the new time will go ahead, let them call me whatever they want. I’m not to blame. I received a recommendation and said I liked the idea.” Chavez wanted it implemented within a week - causing needless chaos - and bungled the explanation, saying clocks should go forward rather than back. If ministers realized the mistake, they said nothing, only smiled and clapped […]

On rare occasions the correct response was not obvious, sowing panic. In a speech to mark World Water Day in 2011, the comandante said capitalism may have killed life on Mars. “I have always said, heard, that it would not be strange that there had been civilisation on Mars, but maybe capitalism arrived there, imperialism arrived and finished off the planet.” Some in the audience tittered, assuming it was a joke, then froze when they saw neighbors turned to stone. To these audience veterans it was unclear if it was a joke, so they adopted poker faces, pending clarification. It never came; the comandante moved on to other topics.

How did a once-great nation reach this point? I read Rory Carroll’s Comandante to find out.

II.

Venezuela was a typical Latin American country - Indians, conquistadors, strongmen - until the discovery of oil in the early 1900s. Foreign oil companies briefly resisted taxation. But over the 20th century the government gradually got them under control. In 1976, they finally nationalized the industry entirely under a government-run company, PDVSA. Venezuela is believed to have more oil - and more oil per person - than Saudi Arabia.

In the 1970s, the Arab Oil Crisis pushed prices up and made Venezuela the richest country in Latin America. GDP per capita approached the level of Italy and Germany. Caracas became an international capital of business and culture.

But it was also one of the most unequal societies in the world. Oil money went mostly to the well-connected elites. These elites ran both major political parties, which agreed not to compete too hard against each other. Whoever was in power served elite interests and kept the masses placated with generous subsidies.

When oil prices dropped in the 1980s, the subsidies dried up. In 1989, mounting anger exploded into a series of riots in Caracas; between 200 and 2000 people died. The government crushed the protests and managed to barely hang onto power.

Enter Hugo Chavez. He was born in 1954, to a lower-middle-class family in an outlying province (later he would falsely claim to have risen from desperate poverty). Young Hugo loved baseball. His favorite player was his namesake, Isaias Chavez, who had risen from the Caracas suburbs to reach the US Major Leagues. When Isaias died tragically in a plane crash, 14 year old Hugo was heartbroken. “I even came up with a little prayer I recited every night, vowing to grow up to be like him.”

When he came of age, he decided to join the army, on the grounds that the military academies had good baseball teams. But to everyone’s surprise including his own, he liked the army. No man can serve two masters, and for a few years, he struggled over which dream to pursue. But finally:

On a day of leave in late 1971, he put on his ceremonial blue tunic [and traveled] to the cemetery where Isaias Chavez was buried. There he asked the dead pitcher forgiveness for abandoning the vow to follow in his footsteps. “I started talking to the gravestone, with the spirit that penetrated everything there . . . It was as if I was saying to him, “Isaias, I’m not going down that path anymore. I’m a soldier now.” And as I left the cemetery, I was free.”

But Chavez stayed the same overly serious, overdramatic young person as always. And his hero-worshipping tendencies found a new target: Simon Bolivar, the Great Liberator, the man who had first won Latin America its freedom from Spain. Comandante seems confused exactly how Chavez ended up so left-wing. Bolivar-worship was par for the course, but most military recruits took it in a conservative direction. It can only say that Chavez met some left-wing activists, and visited Peru when it was making its own left turn. Still, it seems that pretty early, Chavez had come up with an unorthodox fusion of Bolivarism and communism, mixed with a sense of personal destiny. A diary entry from 1977, addressed to Bolivar, said:

Come. Return. Here. It is possible . . . This war is going to take years . . . I have to do it. Even if it costs me my life. It doesn’t matter. This is what I was born to do.

And in 1982, when Chavez was 28, he led two friends to a holy shrine - a tree that Bolivar used to rest under - and:

It was a humid, sticky day, and the friends arrived drenched in sweat, Chavez last. There they plucked leaves, a military ritual, and Chavez improvised another speech, this time paraphrasing Bolivar’s famous 1805 oath: “I swear to the God of my fathers, I swear on my homeland, I swear on my honour, that I will not let my soul feel repose, nor my arm rest until my eyes have seen broken the chains that oppress us and our people by the order of the powerful”. The others echoed his words, and a conspiracy was born.

By the 1990s, Chavez - by all accounts personable and charismatic - had risen through the ranks and made friends with other leading officers. In 1992, when the government that had crushed the recent riots seemed poised to get away with it, Chavez organized a coup (rumor was army leadership was aware, expected him to fail, and let him do it because for complicated reasons it would help them score political points). The coup failed. Chavez surrendered. But the countercoup forces made a fatal mistake. They put Chavez on TV to tell his remaining forces to stand down. He did. But while on TV, he was unrepentant and charismatic and gave a fiery speech. This put him in position to try the Hitler Slingshot Manuever: fail at a coup, get pardoned, and leverage your post-coup fame to seek legitimate election.

Chavez’s pardon came two years later, at the hands of politician Rafael Caldera - who may have been in on the coup all along. Four years afterwards, he won a fair presidential election and took power.

III.

This is the point where I’m supposed to explain how Chavez went from democratically-elected president to dictator. It’s tough, because it’s debatable how much of a dictator he was.

He continued to hold mostly fair elections throughout his reign. His party even lost some of them! He certainly didn’t murder his enemies as consistently as Putin. He wasn’t even consistent about locking them up. Carroll describes one enemy, a judge who sometimes ruled against him. Chavez jailed her, but forgot (?) to take away her cell phone. She kept posting anti-Chavez tirades from her jail cell, Chavez kept posting bombastic responses, but the thought that she was in jail and he could rough her up or at least steal her phone never really got through to him. Part of Chavez’s appeal was that he was more of a clown than a chessmaster, and this percolated through to his dictatorial style.

Instead of firing squads at midnight, Chavez was authoritarian in the way that American conservatives claim that wokeness is “creeping authoritarianism”. He and his network of allies controlled the media, the institutions, and all the good jobs. If you flattered him, the media would say nice things about you, you would get preferential treatment when interfacing with institutions, and could count on a well-paying sinecure at some government department or nationalized company. If you questioned his rule, you would find that every news story about you was negative, and you were locked out of any job besides janitor or taxi driver.

For example: in 2003, the economy sputtered, and opponents sensed weakness. They organized a campaign to recall Chavez. Venezuelan law requires a certain percent of the population sign a recall petition. The opponents got it: three million signatories. Chavez survived the recall and hung on to power. And:

He had warned people not to sign the petition, and now they would pay. A digital record of the three million names was passed to Luis Tascon, a young National Assembly member and specialist in information technology. He posted it on his web site, ostensibly to prevent the opposition from inventing signatories. Thus was born la lista Tascon. The Tascon list. Also known as Chavez’s revenge. It formalised the country’s division. Heretics this side of the ledger, believers on the other. Government and state offices used it to purge signatories from the state payroll, to deny jobs, contracts, loans, documents, to harass and punish, to make sectarianism official. People lost careers and livelihoods and went bankrupt. Fear gripped those who had signed, then it spread to their relatives. On his television show, the president invited Tascon onto the stage and with mock anxiety asked “I don’t appear on your list, do I?”

By April 2005 the stories of blighted lives were creating an international embarrassment, so Chavez publicly declared a halt. ‘The Tascon list must be archived and buried”, he said. “I say that because I keep receiving some letters . . . that make me think that in some places they still have the Tascon list to determine if somebody is going to get a job or not. Surely it had an important role at one time, but not now.”

A year later, Teresita Rondon confirmed that the list was alive and well in Merida. Her job was to apply it, to methodically cross-reference every municipal employee, contractor, job applicant. Teachers, street sweepers, police, doctors, secretaries, ambulance drivers, receptionists, anyone and everyone needed to be checked to determine if they were to be fired, barred, or hired . . . the list, she said, had been transferred and expanded into a new software program called Maisanta, after the commandante’s great-grandfather. It included all registered voters and allowed officials to check their addresses, voting stations, voting participation, political preferences and memberships in missions and other government schemes. It enabled searching and cross-referencing and rated people as “patriots”, “opposition”, or “abstainers”. The Maisanta list was national. Chavez’s order to bury it had been for the cameras. Rondon was one cog in a huge, clanking machine.

It bred a minor industry of corruption because data could be manipulated, she said. “I’ve heard of people who signed paying to become patriots”. Those who couldn’t afford the bribe stayed on the blacklist. “It’s not my fault. I didn’t know this was the job. I can’t look friends in the eye. Some of them are on the list. What am I going to tell them?” Her eyes reddened, and it seemed like she would cry, but she didn’t.

I like this passage. It tells us many things:

-

Chavez has a wicked sense of humor.

-

The accepted way to enact change is to write letters to Chavez and hope he listens to you.

-

Chavez will frequently declare popular policies on his TV show, to great rejoicing, then do the opposite in real life. He controls the media, so there’s no easy way to tell when this is happening.

-

Once cancel culture gets powerful enough, even the enforcers feel gross and guilty, but they do it anyway, because otherwise they won’t have a job, or they’ll be cancelled themselves.

But as much as we complain about this kind of thing in the West, Venezuela has it worse. Partly this is because of how centralized and official it is under one guy. But mostly it’s because Venezuela doesn’t have much private sector or civil society. Remember, think of it as Saudi Arabia with better weather. The (government-owned) oil company is the ultimate source of all wealth. That was true even before Chavez. Chavez then expropriated most private industries, and mismanaged the rest into bankruptcy. But he compensated for this with his own set of oil-subsidized institutions and outright oil subsidies. As always, you get rich (or middle class) by standing in front of the giant geyser of oil money. And Chavez got to control who did that.

IV.

But fine. Let’s set the word “dictator” aside, and try to get back to the story of how he went from weak democratically-elected president to the sort of guy who could get all his opponents blacklisted and destroy all private industry.

Hugo Chavez took office in 1999. At first, he wasn’t much of a strongman:

The young president retained a conservative finance minister from the previous government, improved tax collection, punctually repaid Venezuela’s debts, and pursued traditional economic policies . . . Luis Miquilena, the president’s veteran political mentor and string-puller, quit in despair. “That fake revolutionary language . . . I would say to him, you haven’t touched a single hair on the ass of anyone in the economic sector! You have created the most neoliberal economy Venezuela has ever known. And yet you go on deceiving the people by saying that you are starting the blah, blah, blah revolution.”

But Chavez was biding his time. In mid-1999, he called for a Constituent Assembly to rewrite the Constitution. Chavez’s supporters won 52% of the votes for assembly members, but because Chavez got to set the vote -> seating rules, they got 95% of the seats. The Assembly voted itself the right to remove “corrupt” government officials, which turned out to mean judges opposed to Chavez. It increased presidential power, lengthened presidential terms, made various appointed positions open to election, and eliminated the upper house of the formerly bicameral legislature (it also passed a laundry list of left-wing policy reforms, like giving indigenous peoples guaranteed seats in Congress).

His next target was PDVSA, the oil company. In all the previous decades of corruption, the elites had been smart enough not to injure the golden goose. The oil company was an island of relative competence, run by technocrats, oligarchs, and economists. They fancied themselves above the civilian government, and although they would graciously share revenue with the state, they weren’t going to play by its rules. Chavez played a cat-and-mouse game, trying to use his limited presidential powers to frustrate and humiliate them as much as possible. Finally, he tried a frontal assault:

The president . . . made a very different broadcast on his television show. Ebullient and combative, he had fired and humiliated PDVSA executives, reading out names one by one. “Eddy Ramirez, general director until today, of the Palmaven division. You’re out! You had been given the responsibility of leading a very important business . . . this Palmaven belongs to all Venezuelans. Senor Eddy Ramirez, thank you very much. You, sir, are dismissed.” He blew a whistle, as if he were a football referee. The audience cheered, and the comandante continued working his way through a list. “In seventh place is an analyst, a lady . . . Carmen Elisa Hernandez. Thank you very, very much, Senora Hernandez, for your work and service.” The voice dripped sarcasm, and he blew the whistle again. “Offside!” The broadcast delighted supporters and enraged opponents.

The oil executives and their oligarch supporters called a general strike. Millions of Chavez opponents took to the streets. They were supposed to march to the oil company headquarters, but “spontaneously” shifted course to the presidential palace. Somehow - it was unclear exactly how - there was violence and some of them were massacred. This made the rest even angrier, and they rushed towards the palace to find and depose the President. Chavez fled. Pro- and anti-government forces agreed on a truce where Chavez would go into exile in Cuba, and business leader Pedro Carmona would become acting president. But Carmona quickly alienated everyone, including the military (who had been thinking this was a military coup and they were in control). Chavez’s supporters organized a counterdemonstration and removed Carmona with military backing, and Chavez came right back, triumphantly. Only a few people were charged. There wasn’t much retaliation. Everything was right back to before.

The strike-turning-into-a-coup having failed, the opposition tried an actual strike. For six weeks, companies aligned with the oil leadership - nearly all of them - stopped all production. There were massive shortages. Chavez, always focusing on what was most photogenic, sent in the army to restart production. The bizarre climax of this period was in a soda factory. The cameras rolling, a general burst into the factory, grabbed its hidden stockpile, and started gorging on soda in front of the cameras. Reporters peppered him with questions: isn’t this a threat to private property? Can targeted seizures really make up for a general stoppage of all production? In response to each question, the general let out a giant burp. For some reason this won the heart of the Venezuelan people - “he’s just like us!”.

The general’s expulsion of carbon dioxide from his digestive tract had immediate, enduring political impact, expressing in a way that even Chavez himself had not managed the revolution’s contempt for its foes and determination to prevail. The oligarchs could shut their factories, abuse their power, shriek and shout on their television channels and still lose. Buuuuuuuurgh!

Venezuelans watched the clip, played repeatedly on opposition channels, mesmerized. It made their choice stark. With the belch or against the belnch. Millions called it disgusting. But millions more hailed it as comeuppance for economic saboteurs. One pro-Chavez writer called it an expression of the oppressed’s collective unconscious. “It is part of our Hispanic Arab heritage, of the reconquest.”

Within weeks the strike unraveled. Ambitious businessmen who were not part of the traditional elite helped the government to source and distribute oil, gasoline, food, and other necessities.

With public opinion on his side, Chavez fired most of the workers at the oil company. This destroyed its institutional knowledge and competence. But there was an old Venezuelan joke: “The second most profitable business in the world, after a well-run oil company, is a badly-run oil company.” So the economy only sort of collapsed.

This was when his opponents called the three-million-name referendum to recall him. Chavez had two secret weapons. First, he now controlled all the oil money. Second, he had a good friend in Fidel Castro of Cuba. The two men shared a passion for socialism. And Cuba’s socialist project was well underway and had lots of doctors and social workers. Using his oil money, Chavez paid for his Cuban allies to send in some of Venezuela’s first universally-available social services, including “twenty thousand Cuban doctors, nurses, and other specialists . . . teachers followed to teach the illiterate to read and write . . . credits and training were offered to small agricultural and industrial cooperatives . . . on it went: soup kitchens, subsidized food shops, land titles, flights to Cuba for eye surgery. By the time the referendum was held in August 2004, Chavez’s ratings had recovered, and he won in a landslide.”

From here on, things were comparatively smooth sailing. Partly this was because the opposition had been discredited. Partly it was because Chavez had replaced the independent economy and civil society with oil subsidies and Cuban services loyal to him personally. And partly it was because the US invaded Iraq and drove up the price of oil, and suddenly Venezuela had even more infinite money than the near-infinite amount of money it had before. The amount of money oil consumers were throwing at Venezuela made it almost impossible for a shrewd president who had put himself in position to direct oil revenues to lose. And Chavez (mostly) didn’t lose.

In 2006, he declined to renew the broadcast license for Venezuela’s main independent TV station. In 2007, he called a constitutional referendum to abolish term limits. This time he lost - the book says this was because Chavez had limited control over local government officials who would usually help get out the vote, and the referendum didn’t interest them. Two years later, he tried again, this time abolishing term limits for himself and local officials, and won 54-46. He banned foreign funding for NGOs, accusing them of being tools of American capitalism.

Problems started creeping in around 2008. The global financial crisis didn’t just hit Venezuela directly. It also lowered the price of oil. It became apparent that Chavez had been hollowing out the sort of rule of law it took for the economy to function, and plastering over the cracks with infinite oil money. As the oil money became a mere torrent rather than a giant flood, some of the cracks started to re-open.

Carroll discusses the situation in Ciudad Guayana, Venezuela’s “industrial heartland”. During the late 20th century, the Venezuelan elites had invested in it as the harbinger of a new self-sufficient Venezuela full of high-tech factories and good manufacturing jobs. At first, it seemed to be working.

As part of his popular policies, Chavez had subsidized cheap electricity, until Venezuela’s citizens were “per capita the continent’s biggest energy guzzlers”. In 2010, drought struck Venezuela’s hydroelectric dams, which produced the majority of the country’s power, making such consumption unsustainable. Instead of withdrawing the subsidies, Chavez chose to knife industry. He shut down most of Ciudad Guayana’s factories, some of them so suddenly that “entire plants were ruined”.

Politically, the strategy had largely succeded. By 2011, Caracas, the comandante’s electoral priority, was privileged with regular electricity . . .Chavez’s ratings, which had dipped in 2009 and 2010, began to recover in 2011. Ciudad Guayana had paid the price of having too few voters to threaten the government. Production at Venalum, on which 150 smaller companies depended, had almost halved, and much of that output, because of the damaged machines, was of low quality and unexportable. It needed years of painstaking work and specialised equipment - which the company could no longer afford - to repir the damage. Venalum owed, and couldn’t pay, $25 million to suppliers and multiple times that to the tax authorities and state utilities. The company was broke. So were most of its customers - other state firms in Ciudad Guayana. Gamluch’s balcony overlooked factories, warehouses, cranes, and conveyor belts. It all looked motionless and rusty, like a landscape painting from an earlier era.

The good news was that “the firm had not fired a single worker” - Chavez just added all of them to the oil subsidy payroll!

This seemed typical of Venezuelan companies’ experience:

The comandante had made a genuine effort to transform Ciudad Guayana. He sent Marxist academics to organise worker councils and teach revolutionary theory in 2004. The workers understood solidarity as better pay and conditions, not seizing the means of production, so the initiatives became mired in marathon meetings and squabbles. To break the logjam, the comandante sent political fixers, pragmatists rather than ideologues, who substituted ‘worker control’ for ‘co-management’, a euphemism for top-down hierarchy. Few knew anything about industry or running a business. And they were saddled with excessively generous terms that the comandante in a flush of enthusiasm had awarded to the workers. Under pressure to control soaring costs, the fixers cut investment and maintenance, slowly crippling the plants. Few had opportunity to learn from mistakes because they were swiftly rotated and given additional jobs that kept them in Caracas. The ceaseless, merciless struggle for advancement and survival in [the Chavez administration], in which ministers and courtiers vied for Chavez’s fleeting attention, created a parasitic ecosystem that atrophied the roots of distant realms such as Ciudad Guayana […]

The comandante admitted problems but shunned blame. He accused striking workers of sabotage and said they did not appreciate his generosity. “They must be conscious of the reality.”

And:

Political managers from Caracas with no background in industry. Ideological schools set up in factories. Investment abandoned, maintenance skimped, machinery cannibalized. A catalogue of grievance detailing blunders, looting, and broken promises. Venalum, they said, had for a time stopped exporting to the United States to vainly seek “ideologically friendlier” markets . . . after months of stockpiling, aluminium managers returned to US buyers, but by then the market had crashed, losing the company millions. To curry favor with [the government], another company imported trucks from Belarus, Chavez’s European ally, but the cabins were too high for the region’s twisting paths, terrifying drivers. The trucks were abandoned.

And:

Ciudad Guayana’s decay was replicated across the economy. Venezuela had too much money to collapse, but it peeled, chipped, and flaked into moneyed dysfunction. It was the fate of a system led by a masterful politician who happened to be a disastrous manager.

Chavez used a land law and a billion dollars to seize and distribute a million hectares of privately owned land to thousands of new cooperatives. Their members whooped in delight and rode around on subsidised tractors. But there were no financial controls, and many co-ops disappeared with the mony. Others flailed for want of experience, training, and infrastructure. They lacked spare parts, warehouses, fridges, trucks, roads, buyers. Ninety percent collapsed. The comandante spent another billion and decreed tighter monitoring and training. Officials went too far and choked replacement co-ops with bureaucracy . . . the comandante ordered more equipment and credits and seized another million hectares to try again. This frightened private farmers, who feared expropriation, so they stopped investing and sold off their equipment and herds. Co-ops could not fill the gap, because regulated prices for food starved them of profits. Scarcity spread, and shop shelves went bare. Rather than raise prices, which would have hurt his popularity, the comandante imported ever greater quantities of food. When co-ops protested, saying they could not compete, ministers played dumb. What imports? So much was imported the ports were overwhelmed and 300,000 tonnes rotted in containers. Prices jumped again, so the army arrested butchers suspected of selling over the regulated price. Squads of ruling party officials raided shops suspected of ‘hoarding’. Rather than risk arrest, supermarkets kept stocks bare […]

The oil industry itself atrophied. PDVSA became a bloated hydra so overloaded with social and political tasks it neglected its core business of drilling and refining. Starved of investment and expertise, production slumped. Foreign oil companies made down payments for drilling rights but delayed spending the billions needed to develop the Faja wilderness. They did not trust PDVSA as a partner and feared Chavez could decide one morning to expropriate their investments . . . vertiginous world prices for oil, however, meant even a dyfunctional PDVSA of rising costs and dwindling production earned enough revenue to buy Venezuelans’ complaisance. It did so through subsidies. It subsidised food, subsidised electricity, subsidised mobile phones, subsidised cars, subsidised houses, subsidised almost everything. Not everyone benefitted - you needed contacts, patience, and luck to get some of the juicier subsidies - but the fact that the state offered such things cheaper than private businesses made Chavez lord of patronage and magnamity. He filled the country’s cracks with sweet, sticky honey.

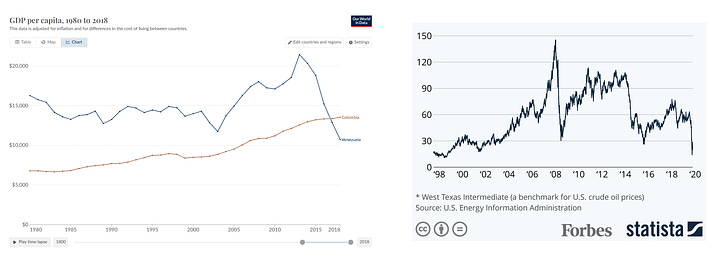

Left: GDP per capita of Venezuela (blue) vs. neighbor Colombia (red). Right: price per barrel of crude oil. When crude starts going up, so does Venezuela’s GDP. But when it starts going down, Venezuela’s economy is revealed to be so hollowed out that GDP crashes even lower than it was before at the same oil price.

Left: GDP per capita of Venezuela (blue) vs. neighbor Colombia (red). Right: price per barrel of crude oil. When crude starts going up, so does Venezuela’s GDP. But when it starts going down, Venezuela’s economy is revealed to be so hollowed out that GDP crashes even lower than it was before at the same oil price.

Chavez was spared the worst of it. He died of cancer in 2013, when crude oil prices were still high enough to disguise some of the damage he did to Venezuela. In 2015, prices crashed, and it became obvious that without his system of subsidies, the economy had completely ceased to function.

V.

So in a few short paragraphs, what went wrong?

There’s a known flaw in democracy. Candidates can temporarily increase their popularity by doing things which are popular even though they’re bad ideas. Guarantee low prices by jailing any merchant who charges above a certain amount. Confiscate land and business from out-of-touch rich people. Declare generous gasoline subsidies for all, payment to be handled later. Do these enough, and the country collapses.

In sufficiently intense electoral competition, why doesn’t everyone do these all the time? Partly you hope for an educated electorate that doesn’t fall for them. Partly you hope that the country has enough non-elected elites that they can stop this kind of thing. And partly you hope that the consequences of such mismanagement accrues quickly enough to hurt the candidates and parties who propose it.

But Chavez was psychologically addicted to maximizing his own immediate popularity any given moment. He was able to use the rhetoric of communism to steamroll over the educated elites who tried to stop him. And he had enough oil money to defy gravity for a very long time, burying the feedback signals that would otherwise have told him to slow down.

So, the usual question: could it happen here? Here are three answers:

1) America is no stranger to politicians wooing the electorate with bad economic policy. The most obvious case is Trump’s tariffs, but it’s silly to pick on something so out-of-the-ordinary when this is such a standard part of the game. Look at the American regulatory state, and lots of it is ruinous ideas that probably sounded good to people who didn’t understand economics. Take a random Chavez proposal, call it “the Green New Deal”, and publish an editorial saying it will “make the one percent pay”, and half the US electorate will start protesting for it immediately.

So a more focused question would be: what are the factors causing it to happen here at some slow rate but no faster? And should we be concerned that those factors will disappear, leading to a Chavez-like collapse?

I don’t have a great answer here. My best guess would be that we don’t have Venezuelan levels of oil wealth, politicians understand that voters will punish them if they destroy the economy, and so they try to avoid doing that. Chavez got saved a couple of times by sudden oil windfalls and the Cubans; without them, he wouldn’t have made it. I suppose that’s true here too.

2) Chavez used the usual dictatorial tools that we’re well-protected against. In particular, he benefitted from a constitutional assembly; he was able to plan it so that a 52% showing by his party led to control of 95% of the seats, essentially letting him rewrite the constitution and gain unlimited power. Most western countries have better constitutional amendment processes than this, so we’re probably safe.

The Chavistas also benefitted from being able to refuse to renew opponents’ broadcasting licenses; I don’t know what our broadcasting license policy is here, but I never hear about this being an issue so I’m guessing we’re probably safe. And the continued independence of Facebook and (especially) Twitter means broadcast TV doesn’t have the same monopoly on information here that it probably did in Venezuela. I think we’re safe here too.

3) Chavez reminded me more of Trump than any of the other dictators I’ve profiled. This surprised me, because the other dictators were “right wing populists”, a designation people often apply to Trump, and Chavez was a left-wing revolutionary. Still, something about him feels deeply familiar. Chavez was, first and foremost, a great entertainer. He kept people watching by being funny, unpredictable, and - by the standards of a usually dignified political system - hilariously offensive. Partly this was because it was politically advantageous for him to have everyone talking about him. But partly he was an obligate narcissist and couldn’t have stopped it if he tried.

He had zero loyalty, ran through ministers quickly, and ended up with a cabinet of mediocrities whose only virtue was complete willingness to flatter him and do whatever he said. He took great photo ops but was too distracted to ever really follow through on his grand plans. He was vicious in insulting his opponents, but too distracted to ever really neuter them entirely.

So Chavez feels like what happens if you get a left-wing Trump who’s a little more competent and then benefits from enough of an oil windfall that nobody can get rid of him. It’s not pretty.

Carroll ends his book at Chavez’s death. He paints a picture of a system centered entirely around one man, his frenetic work schedule, and his cult of personality. Nicolas Maduro appears only as the flatterer-in-chief, a former bus driver with no personality of his own.

Given Chavez’s inability to ever really get rid of his opponents, and his tendency to pick mediocrities who can’t govern on their own, I find it surprising that Maduro has lasted this long, staying in power despite the collapse of the petrostate and Venezuela feeling the full brunt of its bad decisions. This book gives no explanation for why that would happen. A very quick look at Wikipedia suggests Maduro simply used Chavez’s popularity among the military and police sectors to launch a more traditional dictatorship and suspend all elections. Probably there’s something to be learned here about the thin and porous border between illiberal democracy and true dictatorship, but I would want to know more about Maduro and recent history before making any strong claims.

For whatever reason, I find Chavez scarier than most of the other dictators I’ve been reading about. The others seem like aberrations of democracy. Chavez seems like its monstrous perfection: a reminder that in the absence of virtue, what appeals to the people can be the opposite of what’s good for the state. If there’s good news, it’s that his rule was always rather weak, only propped up by the unusual circumstances of Venezuela’s particular resource curse, and required a switch to full dictatorship after one generation.

Carroll writes Chavez’s epitaph:

A sublimely gifted politician with empathy for the poor, the power of Croesus, the result, fiasco. While he thundered about bringing equilibrium to the universe and polarised his country, foaming passions into hate, neighbours built more sustainable economies and tackled long-term poverty. Allies like Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Ecuador saluted the comandante but did not emulate his economic model, for that way lay ruin. Brazil seized regional leadership. Venezuela atrophied. Nothing worked, but there was money and spectacle. An empty revolution, then. No paradise, no hell, just limbo, a bleak misty in-between where ambition and delusion played out its ancient story. The farces and follies did not add up to despotic horror but they bore the melancholy echo of opportunity squandered, of what might have been, and there was the tragedy.