Does Anaesthesia Prove Ketamine Placebo?

The psychiatric study everyone’s talking about this month is ”Randomized trial of ketamine masked by surgical anesthesia in patients with depression”.

Ketamine is a dissociative drug - it produces weird drug effects like feelings of bodylessness and ego death. Recent research suggests it’s a powerful antidepressant. Usually we would try to run placebo-controlled trials. But it’s hard to run a placebo controlled trial of a dissociative. Either you feel bodylessness and ego death (in which case you know you’re getting the real drug) or you don’t (in which case you know you’re in the placebo group). Sometimes researchers try to use an “active placebo” like midazolam - a drug that makes you feel weird and floaty. But weird and floaty feels different from bodyless and ego-dead.

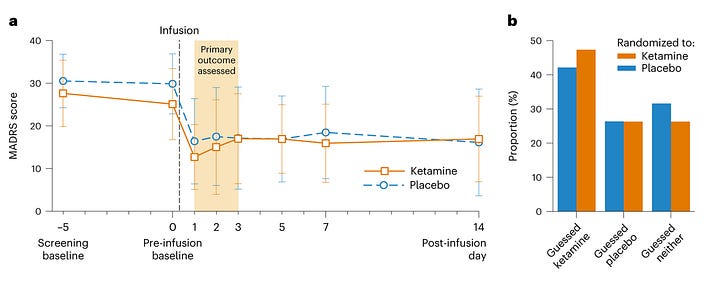

The authors of the recent study go further. They recruited depressed patients who were going into the hospital for routine surgery requiring anaesthesia. When they were anaesthesized, they gave them either ketamine or placebo. Then after they woke up, the researchers asked the patients how depressed they were. These patients had no way of telling whether they got ketamine or not (since they were unconscious at the time). Here are the results:

There was no tendency for the ketamine group to do better than the placebo group!

So, does this prove that ketamine doesn’t work?

Before we get there, let’s look more closely at the graph. MADRS is a depression score questionnaire - you ask patients questions like “how many times have you had thoughts about guilt in the past few weeks?” and give them some number of points based on their answers. The day before the surgery, these patients had an average score of about 29, which gets classified as “moderate depression”.

The day after the surgery, their score plummeted about 15 points, all the way down to ~15, “mild depression”. Why?

Since this happened in both the ketamine and placebo groups, the obvious guess is “placebo effect”. I think that guess is right. But it’s worth noting that this contradicts a story about the placebo effect that’s become pretty popular lately - that it doesn’t exist at all; that it’s just regression to the mean after enough time. This was mentioned in the Against Automaticity essay I criticized recently. I didn’t get around to criticizing that part, but if I had, ketamine studies would have been Exhibit A. Across many studies, ketamine has shown a response within a few hours - and so has placebo ketamine. That’s too fast for depression to regress to the mean, so it must be a real placebo effect. That seems to be what’s happening here - sort of (for reasons we’ll discuss shortly, other ketamine studies are probably a better argument here than this one).

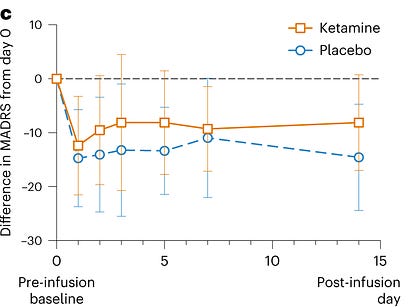

The placebo effect brought scores down 15 points in the placebo group. But there was no extra decrease in the ketamine group: it was also 15 points. Does that mean that ketamine doesn’t work?

It could mean that. Here are a few reasons I’m not so sure.

First, it’s generally hard to measure real effects in the context of strong placebo effects. It requires an assumption that placebo effects and real effects are additive, rather than masking each other. But the MADRS is too complicated for that to be obviously true. Suppose that ketamine affects only two of the many symptoms of depression: insomnia and suicidality. If the placebo effect already got those down to the lowest level possible on the MADRS, then ketamine would have no extra effect. This particular example is kind of a stretch, but something like it affects lots of antidepressant studies - see this post for more. Large placebo effects can saturate the possible curability of the disease, making even strong real effects look very minor . . .

. . . but there’s a difference between “very minor” and “literally zero”, and this study seems to show literally zero. I’m interested in the remission and response numbers:

On post-infusion day 1, 60% and 50% of participants in the ketamine and placebo group, respectively, met criteria for clinical response. . . Remission occurred in 50% and 35% of participants in the ketamine and placebo group, respectively, on post-infusion day 1 [. . .] Hospital length of stay was longer in the placebo group (mean 1.9 (s.d. 1.7) days versus 4.0 (s.d. 3.3) days, P = 0.02).

. . . which suggests there was some slight benefit to ketamine. I don’t really understand why the raw scores and the remission/response numbers are so different, but maybe this is meaningful.

Second, anaesthetics themselves are antidepressants! (thanks to St_Rev for mentioning this). The anaesthetic propofol, used in about 88% of these patients, “may trigger rapid, durable antidepressant effects”, with a purported effect size well above that of SSRIs (these trials are very small, but so was the ketamine trial).

So maybe they were giving all these patients a strong antidepressant, plus half of them a second strong antidepressant. Several studies have shown that two antidepressants don’t always work much better than one, so maybe the ketamine didn’t add much to the propofol.

Third , how sure are we that ketamine works when you’re unconscious? Some people have claimed that ketamine works because of the dissociative experience or ego death or something - you lose your ego for a while, you kind of break out of the self-centered rumination of depression, you get a new perspective. Other people claim that it sort of redirects mental currents, which is the sort of thing that might not happen when you’re unconscious and have no mental currents. I’m pretty skeptical of these claims (for reasons I’ll discuss later), but lots of other people believe them, and wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn that ketamine doesn’t work on patients under anaesthesia.

Fourth , how does surgery affect depression? I’m actually kind of shocked that researchers tried administering the MADRS on post-surgical day 1. MADRS asks - for example - about disturbed appetite, a common symptom of depression. But surgery naturally disrupts appetite, and lots of patients are forbidden to eat anything on their first post-surgical day anyway. MADRS asks about disturbed sleep, but sleep in a hospital ward is also naturally disturbed. MADRS asks about concentration problems, but post-surgical patients are often on lots of painkillers (which will naturally impede concentration) and don’t have anything to concentrate on anyway. I don’t understand how you do a MADRS in the hospital on post-surgical day one and expect to distinguish it from a MADRS on pre-surgical day 0 in a meaningful way. In fact, the claim that you can do this is so weird that I feel like I must be missing something.

Even aside from this, I would expect surgery to have some effect - probably positive - on depression. Surgery gets you out of the house. It’s an interesting experience. It’s a break in routine. It probably means you’re making progress in treating whatever condition you needed surgery for. You get an enforced couple-day rest from all of your usual activities. The joke at the mental hospital I used to work at was that three days in the mental hospital will cure all suicidal patients, whether or not they get any treatment - the sheer boredom of hospital life is incompatible with the level of worked-up-ness you need to consider drastic action.

So I’m not sure we should expect to see much of the effect of ketamine through the quadruple smokescreens of placebo effect, antidepressant effect of propofol, patient unconsciousness, and the MADRS-confounding effect of being in the hospital. I’ll be honest, it still surprises me to see literally zero effect (outside the remission/response statistics). I think this rules ketamine out as a miracle drug that cures everybody of everything. But I don’t think it completely rules out that it’s an okay antidepressant with an effect size of 0.7 or something, like all the other studies say.

I’m defending ketamine because I’ve seen it work pretty well for a lot of patients. It’s no miracle, and I get exasperated when people want to skip all the normal medications and go straight to ketamine because “I heard SSRIs don’t work but ketamine treats depression at its root”. It just seems to work sometimes, for some people.

And my patients’ experience is that it works even at low doses that produce no dissociative or ego death effect. I usually prescribe it at about 70 mg intranasal. Some of my patients report feeling a little drunk or giddy on this amount, but nothing like the k-hole that people report at the really high levels. Other patients report nothing at all, but still feel better. This makes me doubt that you necessarily need an study under anaesthesia to control for dissociative effects. A simple midazolam active placebo would work fine. But also, SSRI studies have shown that active placebos don’t really work any better than inactive placebos. This might be more true for SSRIs (which have boring side effects) than ketamine (which at least sometimes has exciting ones). But it means that when evaluating normal ketamine studies (which risk confounding through inactive placebos) vs. this study (which risks confounding through anaesthesia and surgery), I’m more likely to just go with the normal ones.

I admit this study is awkward, and I find it a little confusing. But I plan to stick with my previous belief that ketamine has an average effect size of 0.5 - 0.7 and is a good antidepressant for some (though not all) people. If the ketamine-is-just-a-placebo crowd want to convince me otherwise, I would update hardest on a trial of 70 mg intranasal ketamine on one side vs. midazolam on the other, x4 weeks, where neither side was able to guess which group they were in, but the drugs were still taken in a fairly normal environment.

Finally, I don’t know what I would do if ketamine was a placebo. Stop prescribing it? You saw the graphs above! MADRS scores went down 15 points, bringing people from moderate to mild depression in a day! This isn’t regression to the mean, it’s pure placebo effect (plus or minus a little propofol). Giving that up would be pretty painful.