Mantic Monday 10/30/23

Manifest

Last month, the Lighthaven convention center in Berkeley hosted Manifest, the first conference for prediction market enthusiasts. By now this has already been covered elsewhere, including in a great article by the New York Times , but here are some particular highlights:

Prediction markets have often existed in a regulatory gray area. A newer market, Kalshi, has tried to cooperate with regulators to become a new kind of fully-legal and highly-regulated platform, but it’s been tough going. The day of the conference, main government regulator CFTC denied Kalshi’s petition to have betting markets on elections (see the first item here for previous discussion). This is pretty discouraging; election betting is the bread and butter of prediction markets, and the government seems to have banned it.

Pratik Chougule leads the Coalition for Political Forecasting, a pro-prediction-market lobbying group. He discussed the CFTC’s recent decision, which was less about the normal factors and more about CFTC bureaucrats’ concern that they would be put in a situation where they had to determine election results. Suppose that Biden beats Trump in 2024, and Trump claims there was election fraud. Normally this is a problem for Congress, election regulators, the courts, the media, and the American people. But if there are election prediction markets, then election fraud would indirectly become a type of financial fraud, and now it is also a problem for the CFTC. I think this is a stretch - one could easily frame the question as “will such-and-such a source certify Biden as the winner of the 2024 election?” and then any fraud is already priced in - but I guess this isn’t how CFTC thinks.

He is not really optimistic about the government liberalizing any time soon. There was a moment in the late Trump administration when something could have happened. But the 2020 election fraud controversy made regulators more paranoid about election integrity, and the FTX collapse made regulators more paranoid about seemingly-innovative forms of online betting. The only good news Pratik has is that CFTC is very busy right now, and it will probably be easy for small projects to continue operating in legal gray areas and not face much regulatory scrutiny unless they do something really wrong or grow too big too quickly.

How do prediction markets go beyond a few hobbyists speculating on politics and become a load-bearing piece of social technology?

Robin Hanson compares this to steam engines. People had steam engines since ancient Greece, but they didn’t catch on until the Industrial Revolution. And part of this is that you can’t just open a stall in the bazaar saying “Steam engines for sale! Get your steam engines!” You need to figure out a specific niche for which the steam engines of your day are economically efficient, become really familiar with that niche, build a steam engine specifically suited to it, and then work with your clients to turn it into a packaged, easy to buy, easy to use solution. For real steam engines, that first niche was pumping water out of coal mines. For prediction markets, it’s . . . what?

Hanson is less sure about this answer than the overall story, but he suggests hiring. You could create some kind of product that companies could buy and give their hiring managers at the beginning of a hiring round, asking them to predict which candidates would get good employee evaluation results or promotions at the end of X amount of time. Even if you’re Manifold or Metaculus or someone who already has a good prediction engine, making this product requires a lot of adaptations. Who should be part of the market? What training should you give them beforehand? What should the resolution criteria be? Hanson thinks that the process of designing this product, answering customer questions about it, and iterating before you sell to the next customer is the kind of last-mile problem whose solution will make prediction markets ready for the big time.

Why aren’t prediction markets used more often in journalism?

Dylan Matthews says part of it is that journalists don’t know about them. But another part is that they don’t expect their editors to know about them, and editors tend to strike out weird things they don’t understand and don’t expect their readers to understand. And editors are right that readers might not understand prediction markets without more context, which might be distracting in the middle of an article about something else.

But also, the media is a dignified, official institution, and it prefers interacting with other dignified, official institutions. It likes being able to say “a professor from Harvard said X”, and not “this guy who does really well betting on Manifold says X”. He talked about wanting to quote a superforecaster from Samotsvety Forecasts, a leading prediction group, but expected his editors to ask why these people with the weird Russian name were relevant or trustworthy. It’s easier to cite someone who is “a fellow at the Forecasting Research Institute”, which has the same kind of official ring as “a professor at Harvard”.

I think the solution here is just an overall rising waterline of prediction market knowledge.

See also:

-

AI forecasting talks by Isabel Juniewicz and Matthew Barnett

-

Jonathan Anomaly on genetic enhancement via polygenic embryo selection (the prediction market connection is strained, but it’s always nice to hear a PGS talk)

-

Local parents (including Malcolm and Simone Collins, Zvi Mowshowitz, and Byrne Hobart) discuss parenting and pronatalism (unless I missed it, there was no attempt to connect this to prediction markets, but it was a great talk)

-

Eliezer Yudkowsky debates Destiny (this was awful, they couldn’t find anything they disagreed on, and they tried to debate the FDA but neither one of them really knew what it did).

-

Stephen Grugett talks about technical issues around how prediction markets work (eg automated market makers) and how to build bots for them.

-

Douglas Campbell and Abhishek Kylasa of Insight Prediction on predicting war.

-

And many more.

Finally, no discussion of Manifest would be complete without mentioning these shirts:

And speaking of Polymarket, they were present in force and promising great things. I am sworn to secrecy on some of them, but they were pretty public about their plans to eventually let users to create real-money markets on topics of their choice, so watch this space.

Manifold.love

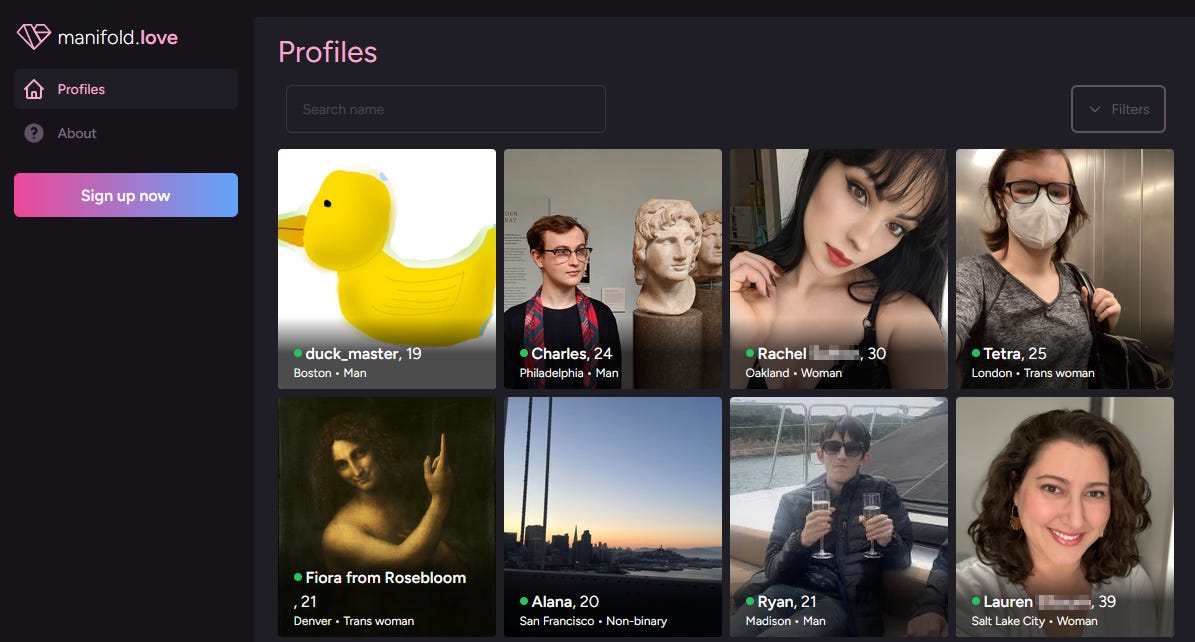

They finally did it and made good on their threats to open up a prediction market dating site, manifold.love:

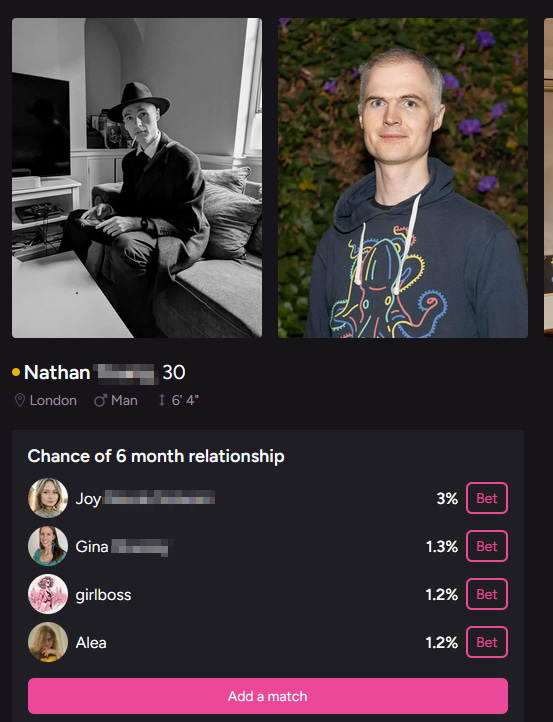

What’s the prediction angle? For any user, you can suggest a match with any other user on the site, and bet on the chance that the match will work (last at least six months):

So far it has the normal problem - not enough women - but otherwise seems fully functional and much more user-friendly than most dating sites. I’ll look into this more later, but some brief preliminary thoughts:

-

Is “chance of a six month relationship” conditional on dating at least once, or unconditional? If unconditional, is there any way for it to resolve no?

-

If unconditional, probabilities should almost always be small, even for people you think are compatible, which is concerning because prediction markets handle small numbers poorly. For example, it only takes a tiny amount of mana to get someone up to 3%, but then it takes a lot more mana to lower them to 2%. So if I have strong evidence that Nathan + Joy won’t work out, I’m not incentivized to bet on this (especially since it’s not clear it can ever resolve “no”)

-

There’s no way to tell whether a specific bet was placed by the person involved or not.

-

…and because most honest match percentages will be so low, it’s easy for an, ahem, motivated bettor to get to the top. Aella, who is very famous, has about 30 potential matches right now. But it would only take about 400ℳ for me to make myself her top match at 20%. Maybe if I like Aella enough to hack the system like this, it’s good for me to come to Aella’s attention - but this is a pretty different use case than it says on the tin.

More on this once it’s had a chance to get used.

Eyeless In Gaza

Prediction markets are sometimes held up as a way to get clarity on controversial news issues. But how do you resolve the prediction market? It’s fine to start a market on whether there was a lab leak at Wuhan, but ten years from now people will probably still be as confused as today.

So instead, you might focus on still-confusing breaking news, and ask what people will believe in a few weeks, once everyone has had a chance to investigate.

On October 17, there was an explosion at or near the Al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza. Since Israel has been bombing Gaza, suspicion naturally fell on them, and many major publications reported the incident as Israeli bombing a Palestinian hospital. But Israel vehemently denied this, and it seemed like a change from their usual policy of giving a warning before bombing civilian areas. Later photos and videos suggested a Palestinian terrorist group had been trying to shoot rockets into Israel, but the rocket had exploded near the launch pad and hit the hospital instead. In between, lots of people with strong feelings on the underlying conflict switched to having strong feelings about who bombed the hospital and which news sources had reported about it more vs. less responsibly.

It looks to me like NYT first reported on this (and attributed it to Israel) at 1:36 EST Tuesday afternoon, sent subscribers an alert attributing it to Israel at 2:32, then changed their headline at 4:01 to be more agnostic. At 9 AM the next morning, it sent out another alert saying that both sides blamed each other and nobody could be sure.

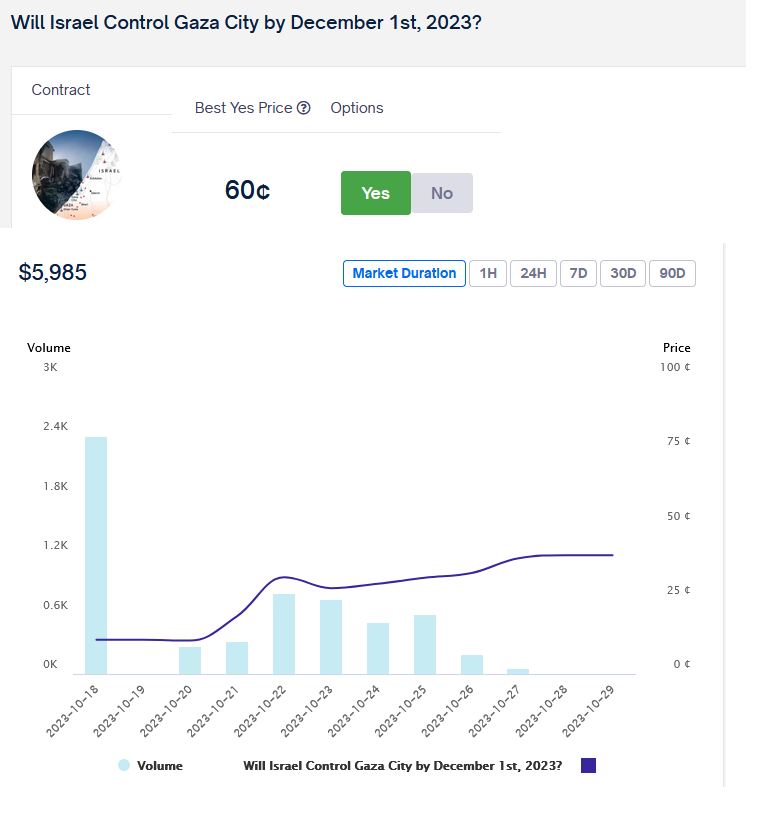

The prediction market started too late to have much of an opinion Tuesday afternoon, but by Tuesday evening it was already down to a 10-15% chance Israel was responsible.

I have mixed feelings on this - it’s important to keep the media honest, but this one hospital bombing has taken on an outsized importance compared to the many other places that Israel (and Hamas) have definitely bombed with no controversy about the attribution.

Still, it’s what people were interested in, and the markets got it right before more traditional sources.

This Month In The Markets

I can’t find any markets on the Middle East topic I’m actually interested in, which is Israel’s medium-term plan. Will they kill some Hamas leaders, then get out? Install a puppet government? Permanently occupy Gaza like they’re occupying the West Bank? These all seem like bad options, but they’re very different bad options, and I haven’t seen much speculation about which is most likely.

[EDIT: Here is an attempt:]

…

Milei looks ready to join the libertarian tradition of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, although the markets are nowhere near as skeptical as this person recently linked on MR.

People seem to trust the new Speaker to avert a government shutdown. Also, look at that volatility!

This one isn’t a market: it’s Manifold users over time. You can see a spike in August from when the superconductor article when viral, and another spike in October. I think that’s from the NYT article, but the site is also benefiting from continuing speculation around the Middle East.

Other Links:

1: Jonathan Zubkoff, winner of the CSPI prediction market tournament, explains his strategy.

2:Demographic survey of Manifold users.

3:“Lancaster University to open first prediction market for Atlantic hurricanes”. AFAICT they’re only accepting experts and you have to apply and provide proof of expertise before you can even see the market. I think this is potentially a missed opportunity - at the very least they should be comparing the experts to something open and seeing what happens.

4: Richard Hanania announces “partnership” with Insight Prediction. So far this looks like him making and adverting some markets and getting a cut of the trading fees. Seems good, but eventually this process should be automatable without the person involved needing to be an official “partner”.

5: I previously wrote about the Existential Persuasion Tournament, where superforecasters tried to convince each other of their views on existential risk (which limited success). Since then they’ve published more information, including on nuclear risk, bio risk, future prosperity, and their next steps (also, they’re hiring).