Pause For Thought: The AI Pause Debate

I.

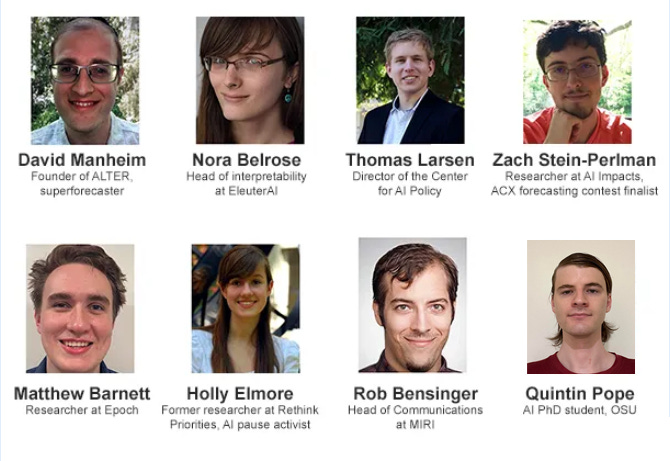

Last month, Ben West of the Center for Effective Altruism hosted a debate among long-termists, forecasters, and x-risk activists about pausing AI.

Everyone involved thought AI was dangerous and might even destroy the world, so you might expect a pause - maybe even a full stop - would be a no-brainer. It wasn’t. Participants couldn’t agree on basics of what they meant by “pause”, whether it was possible, or whether it would make things better or worse.

There was at least some agreement on what a successful pause would have to entail. Participating governments would ban “frontier AI models”, for example models using more training compute than GPT-4. Smaller models, or novel uses of new models would be fine, or else face an FDA-like regulatory agency. States would enforce the ban against domestic companies by monitoring high-performance microchips; they would enforce it against non-participating governments by banning export of such chips, plus the usual diplomatic levers for enforcing treaties (eg nuclear nonproliferation).

The main disagreements were:

-

Could such a pause possibly work?

-

If yes, would it be good or bad?

-

If good, when should we implement it? When should we lift it?

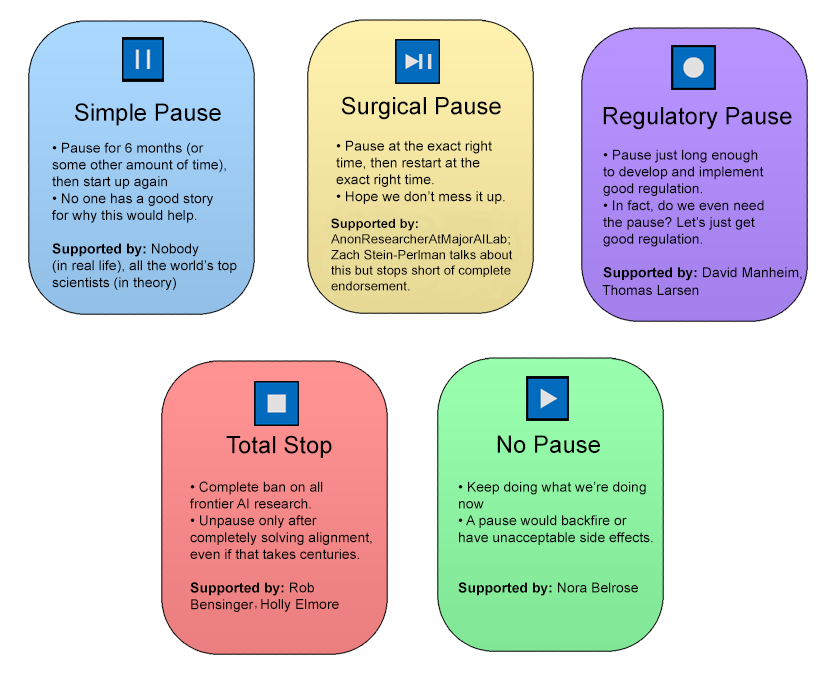

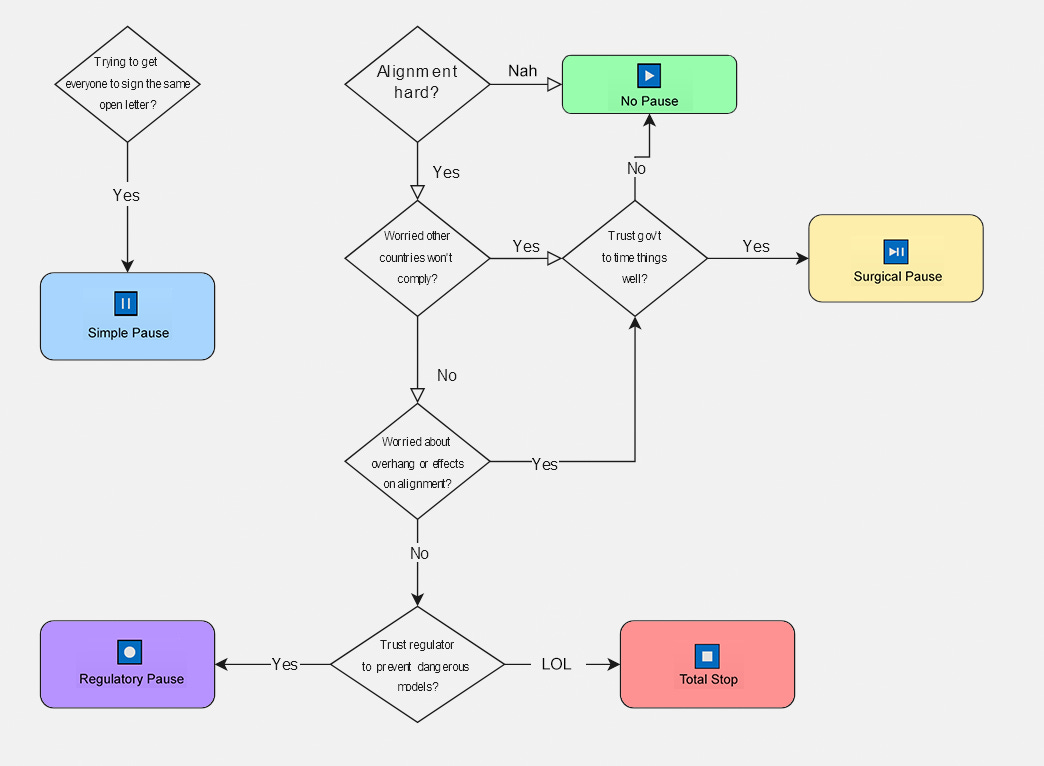

I’ve grouped opinions into five categories:

Simple Pause: What if we just asked AI companies to pause for six months? Or maybe some longer amount of time?

This was the request in the FLI Pause Giant AI Experiments open letter, signed by thousands of AI scientists, businesspeople, and thought leaders, including many participants in this debate. So you might think the debate organizers could find one person to argue for it. They couldn’t. The letter was such a watered-down compromise that nobody really supported it, even though everyone signed it to express support for one or another of the positions it compromised between.

Why don’t people want this? First, most people think it will take the AI companies more than six months of preliminary work before they start training their next big model anyway, so it’s useless. Second, even if we do it, six months from now the pause will end, and then we’re more or less where we are right now. Except worse, for two reasons:

-

COMPUTE OVERHANG. We expect AI technology to advance over time for two reasons. First, algorithmic progress - people learn how to make AIs in cleverer ways. Second, hardware progress - Moore’s Law produces faster, cheaper computers, so for a given budget, we can train/run the AI on more powerful hardware. A pause might slow algorithmic progress very slightly, with fewer big AIs to test new algorithms on. But it wouldn’t slow hardware progress at all. At the end of the pause, hardware would have progressed some amount, and instead of AIs progressing gradually over the next six months, they would progress in one giant jump when the pause ended, and all the companies rushed to build new AIs that took advantage of the past six months of progress. But gradual progress (which allows iteration and debugging in relatively simple AIs) seems safer than sudden progress (where all at once we have an AI much more powerful than anything we’ve ever seen before). Since a pause like this simply replaces gradual progress with sudden progress, it would be counterproductive.

-

BURNING TIMELINE IN A RACE. Suppose that we prefer America get strong AIs before China. If America pauses but China doesn’t, then after the pause we’d be exactly where we were before, except that China would have caught up relative to America. More generally, companies that care most about AI safety are most likely to obey the pause. So unless we’re very good at enforcing the pause even on non-cooperators, this just hurts the companies that care about safety the most, for no gain.

These are counterbalanced by one benefit:

- MORE TIME FOR ALIGNMENT. Maybe we can use those six months to learn more about how to control AIs, or to prepare for them socially/politically.

This benefit is real, but this kind of pause doesn’t optimize it. Technical alignment research benefits from advanced models to experiment on; the Surgical Pause strategy takes this consideration more seriously. And social/political preparation depends on some kind of plan: this is what the Regulatory Pause strategy adds.

Surgical Pause: The Surgical Pause tweaks the Simple Pause to add two extra considerations:

-

WHEN TO PAUSE. If we’re going to pause for six months, which six months should it be? Right now? A few years from now? Just before dangerous AI is invented? The main benefit to a pause is to give alignment research time to catch up. But alignment research works better when researchers have more advanced AIs to experiment on. So probably we should have the six month pause right before dangerous AI is invented.

-

HOW LONG TO PAUSE. The biggest disadvantage of pausing for a long time is that it gives bad actors (eg China)1 a chance to catch up. Suppose the West is right on the verge of creating dangerous AI, and China is two years away. It seems like the right length of pause is 1.9999 years, so that we get the benefit of maximum extra alignment research and social prep time, but the West still beats China.

Obviously the problem with the Surgical Pause is that we might not know when we’re on the verge of dangerous AI, and we might not know how much of a lead “the good guys” have. Surgical Pause proponents suggest being very conservative with both free variables. This is less of a well-thought-out plan and more saying “come on guys, let’s at least try to be strategic here”. At the limit, it suggests we probably shouldn’t pause for six months, starting right now.

Since this involves leading labs burning their lead time for safety, in theory it could be done unilaterally by the single leading lab, without international, governmental, or even inter-lab coordination. But you could buy more time if you got those things too. Some leading labs have promised to do this when the time is right - for example OpenAI and (a previous iteration of) DeepMind - with varying levels of believability.

AnonResearcherAtMajorAILab discussed some of the strategy here in Aim For Conditional AI Pauses, and this Less Wrong post is also very good.

Regulatory Pause: If one benefit of the Simple Pause is to use the time to prepare for AI socially and politically, maybe we should just pause until we’ve completed social and political preparations.

David Manheim suggests a monitoring agency like the FDA. It would “fast-track” small AIs and trivial re-applications of existing AIs, but carefully monitor new “frontier models” for signs of danger. Regulators might look for dangerous capabilities by asking AIs to hack computers or spread copies of themselves, or test whether they’ve been programmed against bias/misinformation/etc. We could pause only until we’ve set up the regulatory agency, and take hostile actions (like restrict chip exports) only to other countries that don’t cooperate with our regulators or set up domestic regulators of their own.

Many people in tech are regulation-skeptical libertarians, but proponents point out that regulation fails in a predictable direction: it usually does successfully prevent bad things, it just also prevents good things too. Since the creation of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1975, there has never been a major nuclear accident in the US. And sure, this is because the NRC prevented any nuclear plants from being built in the United States at all from 1975 to 2023 (one was finally built in July). Still, they technically achieved their mandate. Likewise, most medications in the US are safe and relatively effective, at the cost of an FDA approval process being so expensive that we only get a tiny trickle of new medications each year and hundreds of thousands of people die from unnecessary delays. But medications are safe and effective. Or: San Francisco housing regulators almost never approve new housing, so housing costs millions of dollars and thousands of San Franciscans are homeless - but certainly there’s no epidemic of bad houses getting approved and then ruining someone’s view or something. If we extrapolate this track record to AI, AI regulators will be overcautious, progress will slow by orders of magnitude or stop completely - but AIs will be safe.

This is a depressing prospect if you think the problems from advanced AI would be limited to more spam or something. But if you worry about AI destroying the world, maybe you should accept a San-Francisco-housing-level of impediment and frustration.

A regulatory pause could be better than a total stop if you think it will be more stable (lots of industries stay heavily regulated forever, and only a few libertarians complain), or if you think maybe the regulator will occasionally let a tiny amount of safe AI progress happen.

But it could be worse than a total stop if you expect continued progress will eventually produce unsafe AIs regardless of regulation. You might expect this if you’re worried about deceptive alignment, eg superintelligent AIs that deliberately trick regulators into thinking they’re safe. Or you might think AIs will eventually be so powerful that they can endanger humanity from a walled-off test environment even before official approval. The classic Bostrom/Yudkowsky model of alignment implies both of these things.

David Manheim and Thomas Larsen set out their preferred versions of this strategy in What’s In A Pause? and Policy Ideas For Mitigating AI Risk.

Total Stop: If you expect AIs to exhibit deceptive alignment capable of fooling regulators, or to be so dangerous that even testing them on a regulator’s computer could be apocalyptic, maybe the only option is a total stop.

It’s tough to imagine a total stop that works for more than a few years. You have at least three problems:

-

NON-PARTICIPANTS. As with any pause proposal, unfriendly countries (eg China) can keep working on AI. You can refuse to export chips to them, which will slow them down a little, but their own chips will eventually be up to the task. You will either need a diplomatic miracle, or willingness to resort to less diplomatic forms of coercion. This doesn’t have to be immediate war: Israel has come up with “creative” ways to slow Iran’s nuclear program, and countries trying to frustrate China’s chip industry could do the same. But great powers playing these kinds of games against each other risks wider conflict.

-

ALGORITHMIC PROGRESS. Suppose the government banned anyone except heavily-regulated companies from having a computer bigger than a laptop. Right now you can’t train a good AI on a laptop, or even a cluster of laptops. But AI training methods get more efficient every year. If current research progress continues, then at some point - even if it’s decades from now - you will be able to train cutting-edge AIs on laptops.

-

HARDWARE PROGRESS. Also the laptops keep getting better, because of Moore’s Law.

Regulators can plausibly control the flow of supercomputers, at least domestically. But eventually technology will advance to the point where you can train an AI on anything. Then you either have to ban all computing, restrict it at gradually more extreme levels (1990 MS-DOS machines! No, punch cards!) or accept that AI is going to happen.

Still, you can imagine this buying us a few decades. Rob Bensinger defended this view in Comments On Manheim’s “What’s In A Pause?”, and it’s the backdrop to Holly Elmore’s Case For AI Advocacy To The Public2.

No Pause: Or we could not do any of that.

If we think alignment research is going well, and that a pause would mess it up, or cause a compute overhang leading to un-research-able fast takeoff, or cede the lead to China, maybe we should stick with the current rate of progress.

Nora Belrose made this argument in AI Pause Will Likely Backfire. Specifically:

[A pause] would have several predictable negative effects:

Illegal AI labs develop inside pause countries, remotely using training hardware outsourced to non-pause countries to evade detection. Illegal labs would presumably put much less emphasis on safety than legal ones.

There is a brain drain of the least safety-conscious AI researchers to labs headquartered in non-pause countries. Because of remote work, they wouldn’t necessarily need to leave the comfort of their Western home.

Non-pause governments make opportunistic moves to encourage AI investment and R&D, in an attempt to leap ahead of pause countries while they have a chance. Again, these countries would be less safety-conscious than pause countries.

Safety research becomes subject to government approval to assess its potential capabilities externalities. This slows down progress in safety substantially, just as the FDA slows down medical research.

Legal labs exploit loopholes in the definition of a “frontier” model. Many projects are allowed on a technicality; e.g. they have fewer parameters than GPT-4, but use them more efficiently. This distorts the research landscape in hard-to-predict ways.

It becomes harder and harder to enforce the pause as time passes, since training hardware is increasingly cheap and miniaturized.

Whether, when, and how to lift the pause becomes a highly politicized culture war issue, almost totally divorced from the actual state of safety research. The public does not understand the key arguments on either side.

Relations between pause and non-pause countries are generally hostile. If domestic support for the pause is strong, there will be a temptation to wage war against non-pause countries before their research advances too far. “If intelligence says that a country outside the agreement is building a GPU cluster, be less scared of a shooting conflict between nations than of the moratorium being violated; be willing to destroy a rogue datacenter by airstrike.” — Eliezer Yudkowsky

There is intense conflict among pause countries about when the pause should be lifted, which may also lead to violent conflict.

AI progress in non-pause countries sets a deadline after which the pause must end, if it is to have its desired effect.[8] As non-pause countries start to catch up, political pressure mounts to lift the pause as soon as possible. This makes it hard to lift the pause gradually, increasing the risk of dangerous fast takeoff scenarios.

For every word like “trust” or “worried”, assume I mean “…enough to outweigh other considerations”

For every word like “trust” or “worried”, assume I mean “…enough to outweigh other considerations”

Along with this overall arc, the debate included a few other points:

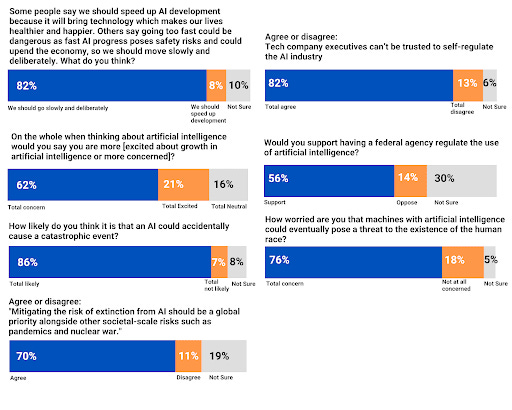

Holly Elmore argued in The Case For AI Advocacy To The Public that pro-pause activists should be more willing to take their case to the public. EA has a long history of trying to work with companies and regulators, and has been less confident in its ability to execute protests, ads, and campaigns. But in most Western countries, the public hates AI and wants to stop it. If you also want to stop it, the democratic system provides fertile soil. Holly is putting her money where her mouth is and leading anti-AI protests at the Meta office in San Francisco; the first one was last month, but there might be more later.

Source: AI Policy Institute and YouGov, h/t Holly

Source: AI Policy Institute and YouGov, h/t Holly

Matthew Barnett said in The Possibility Of An Indefinite AI Pause that it might be hard to control the length of a pause once started, and might drag on longer than people who expected a well-planned surgical pause might like. He points to supposedly temporary moratoria that later became permanent (eg aboveground nuclear test ban, various bans on genetic engineering) and regulatory agencies that became so strict they caused the subject of their regulation to essentially cease to happen (eg nuclear plant construction for several decades). Such an indefinite pause would either collapse in a disastrous actualization of compute overhang, or require increasingly draconian international pressure to sustain. He thinks of this as a strong argument against most forms of pause, although he is willing to consider a “licensing” system that looks sort of like regulation.

Quintin Pope said in AI Is Centralizing By Default, Let’s Not Make It Worse that the biggest threat from AI is centralizing power, either to dictators or corporations. AIs are potentially more loyal flunkies than humans, and let people convert power (including political power and money) into intelligence more efficiently than the usual methods. His interest is mostly in limiting the damage, putting him skew to most of the other people in this debate. He would support regulation that makes it easier for small labs to catch up to big ones, or that limits the power-centralizing uses of AI, but oppose regulation focused on centralizing AI power into a few big, supposedly-safer corporations.

Percent of population in each country saying AI has more benefits than drawbacks. Pope uses this table to suggest AI regulation would be decentralizing, since the furthest-ahead countries are the most eager to regulate. Source: Ipsos; h/t Quintin

Percent of population in each country saying AI has more benefits than drawbacks. Pope uses this table to suggest AI regulation would be decentralizing, since the furthest-ahead countries are the most eager to regulate. Source: Ipsos; h/t Quintin

II.

For a “debate”, this lacked much inter-participant engagement. Most people posted their manifesto and went home.

The exception was the comments section of Nora’s post, AI Pause Will Likely Backfire. As usual, a lot of the discussion was just clarifying what everyone was fighting about, but there were also a few real fights:

-

Gerald Monroe thought that the history of nuclear weapons suggested pauses like this were impossible (because many countries did build nuclear weapons). David Manheim thought it suggested pauses like this could work (because there were some successful arms limitation treaties, and less nuclear proliferation than would have happened without international cooperation). Manheim also brought up the successful bans on ozone-destroying CFCs and on human cloning.

-

Nora thought most treaties like this fail, and a successful one would have to involve some level of global tyranny. David Manheim thought most treaties sort of do some good, even if they don’t accomplish exactly what they wanted, and none of them so far have led to global tyranny. Cf. the Kellogg-Briand Pact for an example of a treaty that didn’t succeed perfectly but was probably net good.

-

Nora thought it was important to give alignment researchers advanced models to experiment with, because the sort of armchair alignment research before interesting AIs existed (eg Bostrom’s Superintelligence) wasn’t just wrong, but fostered dead-end worse-than-nothing paradigms that continue to confuse the field. Daniel Filan objected that Bostrom got some things right and even described something like the direction that modern alignment research is taking. There was a long argument about this, which I think reduces to “Bostrom said some useful theoretical things, speculated about practical direction, and a few of his speculations were right but most now seem outdated”.

-

Zach Stein-Perlman made some good points about the technical factors that made pauses better vs. worse, which I’ve tried to fold into the Surgical Pause section above.

-

Nora thought that success at making language models behave (eg refuse to say racist things even when asked) suggests alignment is going pretty well so far. Many other people (eg Rafael Harth, Steven Byrnes) suggested this would produce deceptive alignment, ie AI that says nice things to humans who have power over it, but secretly has different goals, and so success in this area says nothing about true alignment success and is even kind of worrying. The question remained unresolved.

In How Could A Moratorium Fail?, David Manheim discussed his own takeaways from the debate:

My biggest surprise was how misleading the terms being used were, and think that many opponents were opposed to something different than what supporters were interested in suggesting. Even some supporters Second, I was very surprised to find opposition to the claim that AI might not be safe, and could pose serious future risks, largely because the systems would be aligned by default - i.e. without any enforced mechanisms for safety. I also found out that there was a non-trivial group that wants to roll back AI progress to before GPT-4 for safety reasons, as opposed to job displacement and copyright reasons. I was convinced by Gerald Monroe that getting a full moratorium was harder than I have previously argued based on an analogy to nuclear weapons. (I was not convinced that it “isn’t going to happen without a series of extremely improbable events happening simultaneously” - largely because I think that countries will be motivated to preserve the status quo.) I am mostly convinced by Matthew Barnett’s claim that advanced AI could be delayed by a decade, if restrictions are put in place - I was less optimistic, or what he would claim is pessimistic. As explained above, I was very much not convinced that a policy which was agreed to be irrelevant would remain in place indefinitely. I also didn’t think that there’s any reason to expect a naive pause for a fixed period, but he convinced me that this is more plausible than I had previously thought - and I agree with him, and disagree with Rob Bensinger, about how bad this might be. Lastly, I have been convinced by Nora that the vast majority of the differences in positions is predictive, rather than about values. Those optimistic about alignment are against pausing, and in most cases, I think those pessimistic about alignment are open to evidence that specific systems are safe. This is greatly heartening, because I think that over time, we’ll continue to see evidence in one direction or another about what is likely, and if we can stay in a scout-mindset, we will (eventually) agree on the path forward.

III.

Some added thoughts of my own:

First, I think it’s silly to worry about world dictatorships here. The failure mode for global treaties is that the treaty doesn’t get signed or doesn’t work. Consider the various global warming treaties (eg Kyoto) or the United Nations. Even though many ordinary people (ie non-x-risk believers) dislike AI enough to agree to a ban, they’re not going to support it when it starts interfering with their laptops or gaming rigs, let alone if it requires ceding national sovereignty to the UN or something.

Second , if we never get AI, I expect the future to be short and grim. Most likely we kill ourselves with synthetic biology. If not, some combination of technological and economic stagnation, rising totalitarianism + illiberalism + mobocracy, fertility collapse and dysgenics will impoverish the world and accelerate its decaying institutional quality. I don’t spend much time worrying about any of these, because I think they’ll take a few generations to reach crisis level, and I expect technology to flip the gameboard well before then. But if we ban all gameboard-flipping technologies (the only other one I know is genetic enhancement, which is even more bannable), then we do end up with bioweapon catastrophe or social collapse. I’ve said before I think there’s a ~20% chance of AI destroying the world. But if we don’t get AI, I think there’s a 50%+ chance in the next 100 years we end up dead or careening towards Venezuela. That doesn’t mean I have to support AI accelerationism because 20% is smaller than 50%. Short, carefully-tailored pauses could improve the chance of AI going well by a lot, without increasing the risk of social collapse too much. But it’s something on my mind.

Third , most participants agree that a pause would necessarily be temporary. There’s no easy way to enforce it once technology gets so good that you can train an AI on your laptop, and (absent much wider adoption of x-risk arguments) governments won’t have the stomach for hard ways. The singularity prediction widget currently predicts 2040. If I make drastic changes to starve everybody of computational resources, the furthest I can push it back is 2070. This somewhat reassures me about my concerns above, but not completely. Matthew Barnett talks about whether a temporary pause could become permanent, and concludes probably not without a global police state. But I think people 100 years ago would be surprised that the state of California has managed to effectively ban building houses. I think if some anti-house radical had proposed this 100 years ago, people would have told her that would be impossible without a hypercompetent police state3.

Fourth, there are many arguments that a pause would be impossible, but they mostly don’t argue against trying. We could start negotiating an international AI pause treaty, and only sign it if enough other countries agree that we don’t expect to be unilaterally-handicapping ourselves. So “China will never agree!” isn’t itself an argument against beginning diplomacy, unless you expect that just starting the negotiations would cause irresistible political momentum toward signing even if the end treaty was rigged against us.

Fifth, a lot hinges on whether alignment research would be easier with better models. I’ve only talked to a handful of alignment researchers about this, but they say they still have their hands full with GPT-4. I would like to see broader surveys about this (probably someone has done these, I just don’t know where).

I find myself willing to consider trying a Regulatory or Surgical Pause - a strong one if proponents can secure multilateral cooperation, otherwise a weaker one calculated not to put us behind hostile countries (this might not be as hard as it sounds; so far China has just copied US advances; it remains to be seen if they can do cutting-edge research). I don’t entirely trust the government to handle this correctly, but I’m willing to see what they come up with before rejecting it.

Thanks to Ben and everyone who participated. You can find all posts, including some unofficial late posts I didn’t cover, here.

In addition to a pause causing e.g. China to catch up (with the above downsides), there’s the risk that the US realizes that China is catching up and then ends the pause. (To some extent this is just a limitation of the pause, but it’s actual-downside-risk-y if you were hoping that your ‘pause’ would last through AGI/whatever—with the final progress contributed by algorithmic progress or limited permitted compute scaling, so that labs never have an opportunity to exploit the compute overhang—but now your pause ends prematurely and the compute overhang is exploited.)”

My answer: I think there’s a difference between the regulatory framework for something existing vs. expecting it. It’s constitutional and legal for the US to raise the middle-class tax rate to 99%, but most people would still be surprised if it happened. I’m surprised how easy it is for governments to effectively ban things without even trying just by making them annoying. Could this create an AI pause that lasts decades? My Inside View answer is no; my Outside View answer has to be “maybe”. Maybe they could make hardware progress and algorithmic progress so slow that AI never quite reaches the laptop level before civilization loses its ability to do technological advance entirely? Even though this would be a surprising world, I have more probability on something like this than on a global police state. Possible exception if AI does something crazy (eg launches nukes) that makes all world governments over-react and shift towards the police state side, but at that point we’re not discussing policies in the main timeline anymore.

-

Zach writes in an email: “Much/most of my concern about China isn’t China has worse values than US or even Chinese labs are less safe than Western labs but rather it’s better for leading labs to be friendly with each other (mostly to better coordinate and avoid racing near the end), so (a) it’s better for there to be fewer leading labs and (b) given that there will be Western leading labs it’s better for all leading labs to be in the West, and ideally in the US […]

-

Holly writes in an email: “I also think [you’re] taking the distinction between a mere pause and a regulatory pause too much from the opponents. The people who are out asking for a pause (like me and PauseAI) mostly want a long pause in which alignment research could either work, effective regulations could be put in place, or during which we don’t die if alignment isn’t going to be possible.I suppose I didn’t get into that in my entry but I would Iike to see [you] engage with the possibility that alignment doesn’t happen, especially since [you] seem to think civilization will decline for one reason or another without AI in the future. I think the assumption of [this] piece was too much AI development as the default. “

-

Matthew responds in an email: “I’d like to point out that the modern practice of restricting housing can be traced back to 1926 when the Supreme Court ruled that enforcing land-use regulation and zoning policy was a valid exercise of a state’s police power. The idea that we could effectively ban housing would not have been inconceivable to people 100 years ago, and indeed many people (including the plaintiffs in the case) were worried about this type of outcome.I don’t think people back then would have said that zoning would require a hypercompetent police state. It’s more likely that they would say that zoning requires an intrusive expansion of government powers. I think they would have been correct in this assessment, and we got the expansion that they worried about.Unlike banning housing, banning AI requires that we can’t have any exceptions. It’s not enough to ban AI in the United States if AI can trained in Switzerland. This makes the proposal for an indefinite pause different from previous regulatory expansions, and in my opinion much more radical.To the extent you think that such crazy proposals simply aren’t feasible, then you likely agree with me that we shouldn’t push for an indefinite pause. That said, you also predicted that if current trends continued, “rising totalitarianism + illiberalism + mobocracy, fertility collapse and dysgenics will impoverish the world and accelerate its decaying institutional quality”. This prediction doesn’t seem significantly less crazy to me than the prediction that governments around the will attempt to ban AI globally (sloppily, and with severe negative consequences). I don’t think it makes much sense to take one of these possibilities seriously and dismiss the other.”